Site Navigation

-

Riddles

- Maxims

- Luwas

- Poems

- Songs

- Legends

- Tales

- Short Stories

- Bueabod

- Aklanon Writers

- Books

- About the Author

- Guestbook

Short Stories

WELCOME TO PARADISE

by Eulalio Ibarra

(Ken Ilio)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The summer right after my first year in college, a friend, Russell Ileto, invited a bunch of us to spend a few days in a coral island off Panay in the Visayas. That island, named Boracay, is just a small dot on the map, but it had been known for a while as one of those exclusive playgrounds for wealthy Manilans. It also became known because it was there where the movie "Too Late the Hero" starring Cliff Robertson, Toshiro Mifune, and Michael Caine was shot.

The island became famous because of the pristine white and uninterrupted sand beach that surrounded it and because of puka shells, those naturally formed beads of shells that had collected on shore for centuries, covered by Boracay's fine sand. The shells were dug up, classified according to size and color, and then stringed into necklaces which were then sold in tacky tourist shops as far as Hawaii and Puerto Rico.

The father of my friend, who was a former provincial judge in Aklan where Boracay is, had a resthouse in the island which he rented to visitors and he offered it to us just to get Russ out of his sight for a while.

Boracay at that time was pretty much inaccessible for ordinary Filipinos without a private plane, a yacht, or a helicopter to take them there. There is an old World War II airport in Caticlan, Malay in the main island just across the strait from Boracay where a small plane can land. Since no one in our group owned a plane, yacht or helicopter, we were left with the other choices of transportation to get to the island. Judge Ileto said we could take the Philippine Air Lines flight from Manila to Aklan's capital town of Kalibo in the main island, or an overnight boat ride from Manila to the pier in Batan also in the main island, but these would mean having to go through an ordeal of a reckless and dusty seven-hour truck ride through Aklan and Antique along tricky unpaved roads, and then a half-hour pump boat trip, which was dangerous depending on the season, and we didn't know which season it was at that time, before reaching the island. Or, he said, we could island-hop from Batangas in southern Luzon to Mindoro, to Romblon and then to Boracay.

Always eager for an adventure, three of us - Russell, David and I - opted for the hardest route. We set out to travel by bus from Manila to Batangas City pier in the south of Luzon to take a ferry to Calapan in the island of Mindoro where we stayed overnight, then several rough jeepney rides to San Jose town where we boarded the crowded motorized launch named "MV Toroshita." Why it had a Japanese name, we all wondered. The launch plied through shark infested waters, hopping through several islands in Romblon where we also stayed overnight in the beach, and took another pump boat ride from Tablas in Romblon that eventually brought us to Boracay.

It was a paradise that we never expected.

It was so beautiful on that island. The rough days of traveling from one island to another was well worth the effort. Although Judge Ileto's rest house was somewhat primitive, built of bamboo and pawid thatch and had no running water, it was comfortable and adequate for our purposes. The house was situated among a clump of coconut trees right on the beach on the southern part of the island. It was rustic, lazy, and postcard-perfect.

The beach was amazing, it was wide and stretched on for kilometers and was always deserted. The sand, true to its reputation, was white and fine, like flour, and when the sun was shining, was totally blinding, like the snow on a cloudless winter day in Minnesota, according to David who grew up in International Falls (his father, Dr. Iluminado Cabangbang was a general practitioner there). The waters surrounding the island, was clear, calm, and green, the color of a sparkling bottle of 7-UP, like it was a giant swimming pool. Sitting in the empty beach under the swaying coconut trees, watching the sun set during the early evenings left me with a feeling of cosmic peace. I had never been to such a beautiful yet desolate place.

While the beauty of Boracay overwhelmed me, I felt a sense of foreboding, even a sense of resignation, as if something uncontrollable was going to alter that place. Even the natives who originally came from Ibajay town across the strait, themselves expressed some kind of uncertainty about their future. Many of them, even when they were staunch Catholics, had resorted to the supernatural to guide their lives, offering gifts of food and voodoo dolls to the island's ancient spirits in the caves on the northern shores where the sand was coarse and the water was murky.

Perhaps it was because the winds of change had started to disturb the slow pace of island life. Many outsiders had been trickling into the island, some settling there and spoiling the natural beauty of its surroundings. Boracay was becoming a place where Manila's government officials brought their mistresses without being seen or talked about. Here, they were in a veritable eden, away from the preying eyes of gossip-mongers, yet still near to the big bustle of Manila.

In the middle of the island, fronted by the choicest part of the beach, was a heavily guarded complex of luxurious resthouses built for the sole use of certain government officials. The compound was originally constructed by the now-defunct SALAMIN ("Mirror"), the State Agency for the Linkage and Assimilation of MINorities.

It was highly publicized in Manila dailies that SALAMIN, the world-renowned discoverer of a band of Stone Aged actors in the jungles of Mindanao, was going to embark on an exhaustive study on the life and culture of the vanishing Philippine Negritos, the Filipino aboriginal people who were also found in Boracay. It was the SALAMIN Minister himself who personally chose the gentle Boracay Atis, a ragtag 17-member group of little dark people with kinky hair who camped in the middle of the island, to be the subjects of the pilot study. An anthropology student from the University of the Philippines found out however, that the Boracay Atis were not native to the island. They were nomads from the mountains of Panay who sailed across to Boracay each summer in their communally-owned baroto to work in the coconut plantation of an absentee landlord, a wealthy bachelor from Ibajay.

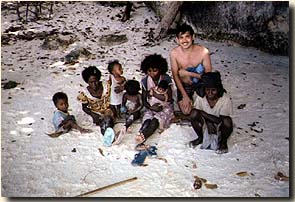

Boracay Atis with a Bisayan from across the strait

Several modern bungalow-style houses of the SALAMIN compound, made of polished anonoo bamboo imported from Malinao town in the main island were still built anyway, right in the area of the Atis' encampment, ostensibly to accommodate leading anthropologists, sociologists and other ists from all over the world. SALAMIN hired the Atis as laborers and carpenters to help in the construction of the palatial structures. When the buildings were finished, a platoon of constabulary soldiers was brought in from Mindanao, away from the war that the government was fighting against Muslim Filipinos, to guard the complex like a fortress, and to keep the Atis from coming back from the rocky crags in the western part of the island where SALAMIN had banished them.

Nong Ome, the caretaker of Judge Ileto's resthouse was a half-Ati himself, and according to him, his people were also employed as part-time maids and errand boys by SALAMIN, perhaps to add a little bit of ethnic flavor to the ambiance in the compound, especially when important people from Manila brought women and foreigners there on week-ends. Well, so much for the well-planned study.

The visitors at SALAMIN usually came by helicopters which landed right on the beach, and during the nights, the visitors and the soldiers guarding them, would hold beach parties with endless bonfires, blaring music, and liquor freely flowing. The parties usually got rowdy, and once, the drunken soldiers fired their armalites indiscriminately, fatally wounding an Ati child who clambered up a coconut tree to watch.

The bonfires particularly angered the islanders. These left ugly black patches on the white sand that could only be cleansed when the next rain came. The party-goers didn't usually care about the ashes because they left when the week-end debaucheries were over. But the islanders did, they usually took pains to cover the remains of the bonfires with fresh sand, making the beach look like it had never been disturbed. The islanders themselves know that their island is a very special place and they make it a point to preserve it in its most natural state.

Members of the Maharlika family, the ruling family that treated the Philippines as their private dominion, used to frequent Boracay, including Ginoong Maharlika himself. They would come by helicopter, but staying only for a few hours and only to water ski. After one of these visits that it was rumored that the Maharlikas wanted the island for themselves. That rumor was fueled further when, at the behest of Gining Maharlika, a big barge landed on the island, and, without notice, hauled a big chunk of the beach - the one in the middle where the sand was the finest and had a blue tinge to it - to God only knows where, maybe to some other white elephant projects the Gining had at that time.

The islanders panicked. They didn't want to suffer the same fate as Balabag, a not-so-distant island to the southwest which was turned into a private hunting ground for friends and cronies of the Maharlika family, complete with big game animals imported from Africa which they stalked safari style. Many small landowners in Boracay unloaded their holdings to a businessman vacationing in the SALAMIN compound, who turned out to be a close friend of Gining Maharlika and who later developed a class AAAA hotel there, for the exclusive use of Madame's jetsetter friends.

About the time of our stay, island life in Boracay was also being punctuated by a new phenomenon - that of visits of Kanos with "sacks on their backs," the islanders said. Travelers they called themselves, as opposed to tourists. They arrived on the island to camp out on the beach at night and sun themselves during the day.

This kind of visitors the Borequenos, as the islanders are known, welcomed, because they did not upset the natural order of their lives. We learned about them during our second night in Boracay when we invited Nong Ome and his friends to share drinks with us, which they appreciated. It was seldom they said that they got invited to have drinks by their visitors. During this night of drinking, these simple fisherfolk told stories about the Kanos who had come to their shores. The stories were told while we were drinking tuba, the sweet native liquor made from the juice of coconut flowers. The Borequenos perceived the Kano travelers to be harmless and in fact found them amusing. The islanders were fascinated with the Kanos' preoccupation with flaunting their naked bodies in the sun for all the people to see. They were also entertained by the Kanos' naivete about their island ways, their interest in living like them, and their penchant for trying anything that the islanders asked them to try.

In return, the natives showed their worth to the Kano visitors, making them feel at home as much as possible. They would show the Kanos anything that the Kanos wanted to see, no matter what they were, even to the point of acting out what the Kanos wanted them to be. The islanders always went out of their ways and means, so as to please their guests from far-away lands.

Many Kanos came to Boracay because of the magic mushrooms which they thought grew nowhere else. They usually paid island children to gather these mushrooms which the Kanos would then make into infusions or cooked with eggs, omelet-style. At first the islanders did not understand why the mushrooms were popular to the Kanos. It only made them giggly or stare blankly into space. There was one Kano, who after drinking the mushroom tea, became so loko in his head that he started to pick imaginary flowers along the main Boracay trail and urinate in front of the children, proudly showing his giant penis to anyone who was interested in seeing it. The islanders laughed at it because it was supot, uncircumcised, which indeed was an embarrassment for an islander to possess. For in these parts of the world, it is customary for all the boys to be circumcised when they reach puberty.

But it didn't matter to the islanders what the mushrooms did to the Kanos. "Hey, who are we to judge? It's their life. As long as our children are making money from the mushrooms, it is alright with us," Nong Ome said. Privately though, they thought that the Kanos were silly, especially in the matter of the mushrooms. If the Kanos only knew that those mushrooms were found practically anywhere where the anwang grazed, because the mushrooms profusely grew in that animal's dung.

Nong Ome told us that there was actually a Kano who lived in the island during the summer months, in the western side, where he had built a house that he shared with the owner of the coconut plantation when the landlord came to the island. The islanders didn't know much about the Kano, he seldom mingled with them. All they knew about him was that every time he appeared on the island, he surrounded himself with several Tagalog-speaking young men who acted like his bodyguards. The islanders said that the Kano always had a new set of bodyguards each time he arrived from Manila.

That revelation about a Kano living in the island was quite unexpected. I wanted to know more about him. I couldn't believe that a Kano would live in a far-flung place like Boracay, granted it was a piece of paradise. When I asked more about the Kano though, Nong Ome didn't say much. All he said was the Kano was competition, because he also accommodated paying visitors in his house. Nong Ome added that the Kano had an advantage over him because most Kanos who came around usually stayed at the place owned by one of their kind. "Patronize your own, baea," Nong Ome said in his heavily-accented English.

The next day, I excused myself from David and Russell and went on my own expedition around the island. I found myself straying toward the western side, to check out where the Kano lived. I wasn't quite sure why I did it, I didn't know what my going there would accomplish. Consciously or unconsciously, I wanted the Kano to "discover" me and perhaps include me in his entourage.

The Kano's house, I found, was further inland and built low amongst the lush tropical vegetation. While I was on the path which snaked through an orchard planted with avocado, papaya, sineguelas, and kasuy trees, I was imagining that after meeting with the Kano, he took me into his fold - and bring me to America - a fantasy that had been forming in my mind after I had read that a rich Kano had brought his Filipina pen pal out to the isteyts.

When I arrived at the Kano's place though, I found his bungalow deserted. The Ati caretaker who came out from the back of the house said that the cottage was locked and the Kano was in Manila. He would be back some time during the next month. "If you're looking for a place to stay," the Ati said, "try Judge Ileto's cottage in the middle of the island. I'm sure Bartholomew would be happy to accomodate you." He sounded apologetic.

I thanked the Ati for his suggestion and left the Kano's compound, feeling silly for indulging in my fantasies. Back at Judge Ileto's cottage to rejoin my friends, I was somewhat dejected and wished that I had never gone to the Kano's place at all. Because, suddenly, Boracay had lost its appeal to me.

_____________________________

Ni

Melchor F. Cichon

Revised February 12, 2002

“Lintik nga onga ron a, alas siete eon it gabii, owa pa gihapon kauli,” si

Nanay ro naghambae.

“Hambae na kainang agahon, mabakae kuno imaw it libro sa mental health, pero

owa man imaw mag-agi kakon sa opisina kainang hapon agud magbuoe it kwarta,”

dugang pa gid ni Nanay.

Si Nanay hay clerk sa munisipyo it Lezo. Kuwarinta eon ra edad. Hasta sa abaga

ra buhok. Ag pirme nga pustora kon magsueod sa opisina.

“Basi kon may gin-agtunan eang si Inday, ‘Nay,” ako ro nagsabat.

Si Inday hay nagatuon sa U High School, fourth year. Ku nakataliwan nga dag-on

hay imaw ro napilian nga editor-in-chief sa andang school organ. Ugaling

mahina ra ueo sa physics. Kon baga, pakabitkabit ra grado sa physics, pero 95%

ra grado sa communication arts. Ku nakataliwan eang nga dominggo imaw

nagsilibrar ka 16th nga kaadlawan. Daywa man lang kaming magmanghod. Imaw ro

kamagueangan. Sang dag-on eang ro ueot namon.

Kon amat hay ginasugid nana kakon nga natak-an kuno imaw magtuon sa baeay ay

kon una ngani kuno si Nanay hay owa’t preno ra pagminueay. Maski sa oras it

pagkaon hay sige ro anang pinangisog. Owa eon lang ngani kami gaimaw kana sa

lamisa kon kami mag-ilabas or mag-ihapon ay kon una kami hay sermon eang ro

amon nga matueon. Abu gid dayon nga masakit nga istorya ra ginahambae kamon.

Kesyo owa kami gatuon, kesyo alas nuybe kami kon magkatueog kon Lunes hasta

Huwes . Pero owa kuno kami ginaduyog it temprano kon Biyernes it gabii o kon

Sabado sa pagtinan-aw it TV o beta. Kon agahon, owa man kuno kami gabugtaw kon

indi pagpukawon, kesyo gapauna-una kuno kami sa comfort room kon hana eon nga

matunga ro tanan sa pag-ihapon. Sige eang kuno ro among omog sa eabahan.

Kanugon eang kuno ro ana nga ginagastos sa pagpatuon kamon. Owa gid kuno

kami’t ginatao nga kabaeaslan kana. Mayad eang kunta kuno kon mga eskular kami.

Pero gakabitkabit eang kuno ro among mga marka sa klase.

Kon painuinuhon namon, medyo may rason si Nanay, ugaling natak-an eang galing

si Inday magpinamati ku baba ni Nanay.

Ag ako man.

“Itsong,” ako ro ginatawag ni Nanay, “Linglinga abi sa bintana kon nag-abot

eon ro maldita ngato. Malintikan gid imaw karon sa anang pag-abot.”

“Indi eon, ‘Nay, ah! Mauli gid ron. Isaea pa masakit pa rang ueo.”

“Isaea ka pa! Owa mo pa gin-ubos ro tuba ni Pilay! Pareho gid kamo king Ama!

Owa’t hasayran kundi maghinilong! Owa’t bale nga owa kita’t suea basta eang

nga may iung-ong. Mayad kunta kon mag-inum eang, ro maeain hay ginaeaktan pa

it baye.”

“Dalia! Tan awa to!” sugpon pa ni Nanay.

Nagbangon ako sa ginaeugban ko nga mahabang sopa nga maeapit eang sa bintana.

“Owa ‘Nay!”

“Agtuni to sa may karsada.”

Nanaog ako sa baeay ag nag-agto sa may karsada. Mahayag ro buean kato ag abu

nga bituon sa eangit. Gintan-aw ko sa karsada paadto sa poblasyon it Lezo. Sa

Baryo Sta. Cruz kami ga estar. Ro amon nga baryo hay isaea sa 17 nga baryo it

Lezo. Sa binit it karsada ro among baeay, seguro mga sangka kilometro ra

kaeayo sa banwa it Lezo.

Owa man ako’t nakita nga Inday. Rang nakita hay si Lola Weta, nanay ni Nanay.

Gapauli eon imaw kato. Mga singwenta metros man lang siguro ro baeay nanday

Lola kamon.

Nagbisa ako sa alima ni Lola Weta.

“Kaeuy-an ka’t Diyos.”

“Ham-at iya ka pa sa karsada? Gabii eon a,” hambae ni Lola Weta.

“Ginatan-aw ko kon nagaabot eon si Inday. Owa pa gihapon imaw kauli. Nagabukae

eon ngani ra dugo ni Nanay.”

“Ham-an, siin si Inday nag-agto?”

“Tao ngani.”

“Ham-an gin-akigan eon man imaw ni Nanay mo ay?”

“Tao. Kaina eang ako nag-uli.!”

“Ham-an, siin ka man naghalin?”

“Naghapihapi kami rito ni Budoy sa tindahan ni Pilay. Birthday abi nana.”

Si Budoy hay klasmeyt ko sa grade six, kaidad ag kahampang ko halin sa maisot

pa kami.

May nagpundo nga traysikol, maeapit kamon ni Lola Weta.

“Haron eon man gali imaw.”

Ginpaeapitan ko imaw ag ginsinghanan sa sitwasyon sa baeay.

“Hala ka Inday,” hambae ko, “pangisdan ka gid ni Nanay. Gabii eon, owa ka pa

gihapon kauli.”

Gin-agbayan ako ni Inday ag ginharuan sa uyahon.

“Ay, si Lola gali! Mayad nga gabii. Pabisa ako.”

Ginpaeapit ni Lola Weta ro anang tuo nga alima kay Inday. Ginbuytan ni Inday

ro alima ni Lola Weta ku anang tuo nga alima ag ginduot na ra sa anang dahi.

“Kaeoy-an ka’t Diyos!” hambae ni Lola.

“Siin ka naghalin nga nadueman ka?” pangutana ni Lola.

“Sa klasmeyt ko. May gin obra kami nga assignment.”

“Pasinsiyaha eon lang si Nanay mo. Basi kon may problema.”

“Huo ‘La,” sabat ni Inday.

“O, sige mag-uli eon kamo.”

“Malieon ‘Tsong.”

Gin agbayan nana ako.

“O,” hambae ni Inday kakon, “daw mahuot ka ah. Siin ka eon man nag-inom?

“Sa party ni Budoy. Naghapihapi kami sa tubaan ni Nay Pilay. Sangbol man lang

rato, ah. Chicken feed!”

“Sangkagalon siguro.”

Pag-abot namon sa baeay, eumopok dayon ro bulkan ni Nanay.

Lumingkod ako sa

sopa sa amon nga sala, samtang si Inday hay nagatindog maeapit kakon. Gin

hukas nana ka siki ra sapatos. Bitbit pa gihapon ra bag.

“Ay, nga baye ka! Owa ka gid gapati kon hambaean. Hambae ko gid kimo nga indi

ka mag-uli it gabii, ham-at makaron ka eang?”

Naghipos eang si Inday.

Pero nagbuga pa gid ro bulkan ni Nanay.

“Owa ka kasayud nga abu nga mga baye nga ginareyp ag ginasueod sa saku

pagkatapos patyon? Paris kahapon, may sangka daeaga nga ginreyp ag ginhaboy sa

idaeom it taytay pagkatapos patyon.

“Si Nanay naman, ano ring pag-aeom kakon, owa eon gid gabasa it peryodiko?”

“Gali man! Hay ham-at gabii ka eon mag-uli?”

“May amon nga gin obra nga assignment.”

“Assignment eang siguro. Basi kon siin-siin ka eang nag-agto!”

“Ano ka man!”

“Ag ano gali ratong habatian ko kay Maring Osang sa madyongan nga

gapaagbay-abgbay ka kuno rito sa plasa ku isaea nga adlaw? Hoy, baye ka, indi

ka pa ngani kantiguhan magtug-on, gakiringking ka eon!”

Namuea ra uyahon ni Inday. Pinusdak na ra bag sa sopa nga ginalingkuran ko.

Nagwasaag ra sueod nga notbok, libro, lapis, bolpen, lipstick, ag iba nga

butang.

“Aba! Aba!, padayon ni Nanay. “Aba, maisog ka pa, ha! Eapit baea riya ay

tuslion ko gid ring sungad.”

Nagduhong eang si Inday sa anang ginatindugan. Pero nakita ko nga ginaangkit

na ra bibig ag nageapad ra mata.

“Sa matuod ‘Nay, natak-an eon gid ako sa baba mo. Pahuwayi man anay baea ako

agud makapatawhay man rang ueo. Owa pa ngani ako kalingkod nagratrat eon ring

baba. Owa mo pa ngani masayri kon siin ako naghalin, pinusdakan mo eon ako

dayon king baba. Ag hanungod sa sugid ni Osang, owa ron it kamatuoran. Ro

matuod hay may gusto kakon da unga nga si Rey ugaling owa man ako’t gusto

kana. Hayskul pa eang ngani ako, ginasunod-sunuran eon nana ako. Tsura lang

niya. Ano ako, karne nga por kilo? Siguro nagsugid ra mabuot nga unga kay

nanay na nga sang dangaw ra dila ag amo man da arangka kimo. Ag dayon man ring

pati kana. Maski imaw eon lang ro habilin nga eaki sa kalibutan, indi gid ako

kana. Sayod ro tanan nga ro tanan nga tubaan riya sa Baryo Sta. Cruz hay

ginaung-ungan na hasta magkamang imaw mag-uli. Sayod ro tanan nga imbes

magsueod imaw sa klase hay igto't a imaw sa bilyaran. Amo ra nga dise-utso eon

ra edad, first year high school man imaw gihapon. Indi ko gusto nga maeansang

kita sa pagkaimoe. Indi ko gusto nga rang mapangasawa hay owa’t ginapanan-aw

nga hin-aga.

“Sia, sia. Matuod man o kon indi ro habatian ko, basta rang gusto hay mag-uli

ka’t temprano agud indi maglibog rang ueo. Tapos!”

“Pero ‘Nay, intindiha man baea rang sitwasyon. Kon gauli ako’t owa sa oras,

indi ka magpiniino nga nagabigabiga eon ako. Kasayod ka man nga gin-utdan

kita’t telepono ay daywang buean eon kita nga owa kabayad, paano ko mahambae

kimo nga may importante ako nga aeagtunan? Mayad man kunta kon sobra rang

allowance, makauli ako riya ag mageaong. Haeos owa eon ngani ako gamerienda

agud magtipid ako. Ag kon amat, kon mageaong man ako, indi ka man magsugot.”

“Ham-at indi kon sa kamaeayran man lang.”

“Kamaeayran man ro gin agtunan ko kaina. Gin-obra namon kang klasmeyt ro among

assigment sa physics. Kasayod ka man nga mahina ako runa. Ag owa man it

gabulig kakon iya. Kon iya kunta si Tatay hay mabuligan nana ako. Pero igto

man imaw sa anang kirida! Ag kon iya ko man tun-an, indi man ako

makakonsentreyt ay puro wakae man lang rang ginapamatian. Mayad eang kon may

bisita kita, malinong ro atong baeay. Pero kon owa…”

“Anong eabot ko! Owa man ako rito sa gin-agtunan mo! Isaea pa baye ka!”

“Gali, ano kon baye? Porke baye, indi eon gali ako makapanaw? Ay, imaw ro

malisod katon ay kon baye ngani, haeos higtan mo eon lang. Ano eon lang ro

matabu katon kon pirme eon lang sa baeay ro baye? Amo ra nga indi mag-uswag ro

atong banwa ay owa naton kinataw-an it tsansa ro mga baye nga magpakita nga

masarangan man nanda nga mag-apin ku andang eawas ag magpangita ku andang

gusto. Imaw ngani nga nagtuon ako agud mag-uswag kita. Karon higtan mo ako

riya sa baeay? Ay! Tapos eon ro oras it binukot. Nakaabot eon ro tawo sa buean!”

“Anong ginahigtan? Gusto ko eang hay mag-uli ka’t mas temprano agud makalikaw

ka sa disgrasya. Ag makabulig ka man riya sa pageaha it atong ihapon.”

“Pero gahalong man ako. Owa man ako gapabaya.”

“Sia, sia. Basta rang gusto hay mag-uli ka’t temprano agud indi maglibug rang

ueo.”

“OK!”

Nag-init rang ueo sa diskusyon nandang daywa.

“Puwede ba, tapusa eon don! Kon indi kamo maghipos, malintikan gid kamo kakon!”

hambae ko.

Naghipos si Inday. Pero si Nanay, sigi pa gihapon ra wakae.

“Andam ka eang, pag nag-uli ka pa nga bagii eon, matueog ka gid sa guwa. Ag

kon may matabu kimo, indi ka gid magpangayo it bulig kakon, nga lintik ka!

Buwisit nga pangabuhi ra!”

Owa nagsabat si Inday. Pero pinusdak na ra bag ag dumiretso sa anang kwarto.

Binuksan na ra kwarto ag gin-bang ro pwertahan.

“Maldita gid matuod!” hambae ni Nanay.

“Tsong, pueota ra gamit ku maldita ngaron ag daehon mo kana.”

“Pabay-I! Pueoton nana ron kon gusto na!”

“Pueota eon ag itao kana!”

Ginpueot ko ro mga nagwasaag nga gamit. Ginsueod ko sa anang bag ag gindaea sa

kwarto ni Inday.

“Inday.”

Owa imaw magsabat. Nabatian ko nga gapisngo imaw.

“Inday.”

“Sueod. Bukas ron.”

Nagsueod ako sa anang kwarto. Nagbangon imaw ag naglingkod sa anang kama.

Paglingkod ko, ginkupkupan na ako.

“Day, indi ka eon magtangis. Imaw gid man ron si Nanay. Mahae ka nana, ugaling

indi eang imaw makahambae sa manami nga paagi. Aburido eang ron imaw. Hasayran

naton nga ginakueang kita’t kwarta ag may mga baeayran pa kita nga kuryente,

telepono. May adlaw-adlaw pa kita nga baeakeon nga suea. Pero ‘Tsong, owa man

ako galakwatsa o gabigabiga, bukon abi?”

Huo, sayod ako karon. Ag gapati ako kimo. Pero, ayaw eon it tangis."

“Sige.” Pero gapisngo man imaw gihapon.

“Pero rang owa nailai hay pangisdan ako maski owa ako’t saea.”

“Mayad pa tag iya si Tatay. Maski gakaeayo pirme ra baba ni Nanay, gahipos

eang si Tatay. Pirme pa kita gaagto sa SM kon Dominggo ag magkaon it ice

cream. Lintik nga Magdalena ron. Gintintar pa gid nana abi si Tatay. Alinon

abi ay babaan man si Nanay. Ingko owa eon it bili si Tatay kon anang mueayon.”

“Pero ‘Day, tandaan ta eang ro bilin katon ni Tatay. Buligan ta si Nanay, ha?”

”Sige, sige.”

Nag-apir kami ni Inday.

“Pero, ‘Tsong, kon , kon makauli ako it eampas sa alas sais, ikaw ro magbukas

kakon it geyt ha?”

“Ang lagay ba naman, eh.”

Tinapik na rang abaga.

Tumindog ako ag gumuwa sa anang kuwarto.

PAGKAAGAHON. Alas kuwatro pa nagbugtaw si Inday. Nagtug-on imaw ag nageaga it

itlog. Pagkaeaha, nagpamahaw ag dayon ra panaw sa eskuylahan. Hambae na kakon

hay may oratorical contest kuno imaw nga agtunan. Imaw kuno ro representative

ku andang eskuylahan.

Sa adlaw ngato hay temprano man ako nagpanaw. Gin-agtunan ko si Tatay sa anang

number two ay may ginapangayo ako nga kwarta para sa akong project sa among

Geometry. Owa ako mag-eaong kay Nanay. Mainit pa rang ueo kana.

Pagbalik ko pagkahapon, owa si Nanay. Katu anay hay ona eon imaw sa pag-abot

ko sa baeay halin sa eskuylahan. Gin-agtunan ko ro baeay ni Nay Osang kon siin

imaw gamadyong. Owa imaw rito. Kinuebaan ako. Nagdiretso ako sa baeay nanday

Lola Weta. Ginsugid nana nga sa Kalibo si Nanay sa Tumbukon Memorial Hospital.

Nabungguan kuno si Nanay it traysikol paghalin nana sa andang baeay. Ginhatod

nana kuno si Nanay sa ospital sa Kalibo.

Nagdaeagan ako pauli ag dali-dali nga ginbuka rang buo sa dingding.

Ag sumakay

it dyip paagto sa Kalibo. Pag-abot ko sa Kalibo hay sumakay ako’t traysikol

paagto sa ospital. Pag-abot ko rito hay igto man gali si Inday ay ginsugiran

kuno imaw ka anang klasmeyt. Bitbit na ra trophy. Ro siki ni Nanay hay

ginbitay ay may bale.

“Nay, ano ro natabu?” hambae ni Inday. “Pageaum ko hay magkalipay kita ay may

trophy ako nga ipakita kimo. Nagdaog ako’t first prize sa oratorical contest

kaina.”

Naghiyum-hiyum si Nanay. Ginbuytan na it hugot ro paead ni Inday. Ag naghambae

dayon si Nanay.

“Nag-agto ako kanday Lola mo. Nagpangayo ako’t bulig ay owa eon kita’t

inugdaeawa’t bugas. Gintaw-an man ako’t kuwarta, ugaling may paaman pa nga

basoe. Bukon abi’t si Tatay mo ro gusto ni Lola mo. Paeahilong ag palikiro abi

kuno si Tatay mo. Imaw ron ro akon nga ginapanumdum samtang gatabuk ako sa

karsada. Owa ako kapan-aw nga may gasumpit gali nga traysikol. Mayad ay

gindaea eagi ako riya ni Lola mo.”

“Si Tatay mo?” pangutana ni Nanay.

“Mayad man imaw. Gintaw-an na ngani ako it sanggatos para sa project ko. Pero

gamiton ta ra sa bueong mo. Mayad ngani owa ko pa magamit. Ginbuka ro man rang

buo. Hara ho, mga singkwinta pesos ra siguro.”

“Huo gali ‘Nay,” sugpon ni Inday. , “may premyo man gali ako nga kwarta, owa’t

eabot sa trophy. Limang gatos ra. Gamiton man naton ra sa bueong mo.”

Nagtueo ra euha ni Nanay. Pinahiran ni Inday it tissue paper.#

Revised: August 17, 2003

Image of the Month

Other links

Best Viewed

With

IE 4.0 or higher

800x600 Resolution

JavaScript Enabled