Tropical Rainforest Plants

More than two thirds of the

world plant

species are found in the tropical rainforests: plants that provide shelter and

food for rainforest animals as well as taking part in the gas exchanges which

provide much of the world oxygen supply. Rainforest plants live in a warm humid

environment that allows an enormous variation rare in more temperate climates:

some like the orchids have beautiful flowers adapted to attract the profusion of

forest insects. Competition at ground level for light and food

has lead to evolution of plants which live on the branches of other

plants, or even strangle large trees to fight for survival. The aerial plants often gather nourishment

from the air itself using so-called air roots? The humidity of the rainforest

encourages such adaptations which would be impossible in most temperate forests

with their much drier conditions.

More than two thirds of the

world plant

species are found in the tropical rainforests: plants that provide shelter and

food for rainforest animals as well as taking part in the gas exchanges which

provide much of the world oxygen supply. Rainforest plants live in a warm humid

environment that allows an enormous variation rare in more temperate climates:

some like the orchids have beautiful flowers adapted to attract the profusion of

forest insects. Competition at ground level for light and food

has lead to evolution of plants which live on the branches of other

plants, or even strangle large trees to fight for survival. The aerial plants often gather nourishment

from the air itself using so-called air roots? The humidity of the rainforest

encourages such adaptations which would be impossible in most temperate forests

with their much drier conditions.

Most tropical rain forest plants are exotic and very beautiful. Orchids and

bromeliads for example are found throughout the canopy and under-story. The

flowering Rafflesia arnoldi which grows on the forest floor has the largest

flower in the world measuring up to 1 metre across. Unfortunately it smells like

rotting meat! However the odour attracts flies which carry out the necessary

pollination.

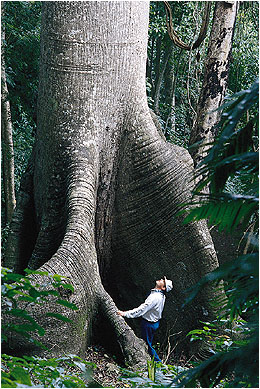

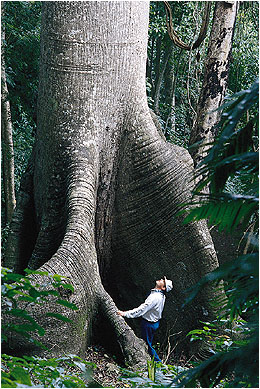

The huge top layer trees are also quite strange. Many of them have huge base

fins known as buttresses, which help support them in the poor soil, and prevent

them being blown over by the high winds that can accompany the monsoon. Other

trees send their roots down from their branches to provide extra support. Many

trees have also evolved protection from leaf eating insects and animals, as they

produce disagreeable chemicals in their leaves making them unpalatable. Others

grow spines on their trunks and branches making it hard for animals to reach

their leaves. Some have hollows in their branches for ants to nest in, and they

return the favour by attacking those insects and vines that can harm the tree.

Most tropical forest soils are very poor and infertile. Millions of years of

weathering and torrential rains have washed most of the nutrients out of the

soil. More recent volcanic soils, however, can be very fertile. Tropical rain

forest soils contain less organic matter than temperate forests and most of the

available nutrients are found in the living plant and animal material.

Most tropical forest soils are very poor and infertile. Millions of years of

weathering and torrential rains have washed most of the nutrients out of the

soil. More recent volcanic soils, however, can be very fertile. Tropical rain

forest soils contain less organic matter than temperate forests and most of the

available nutrients are found in the living plant and animal material.

The soil of a

tropical rainforest is only about 3-4 inches (7.8-10 cm) thick and is ancient.

Thick clay lies underneath the soil. Once damaged, the soil of a tropical

rainforest takes many years to recover.

Temperate rainforests have soil that is richer in nutrients, relatively young

and less prone to damage.

Constant warmth and moisture promote rapid decay of organic matter. When a tree

dies in the rainforest, living organisms quickly absorb the nutrients before

they have a chance to be washed away. When tropical forests are cut and burned,

heavy rains can quickly wash the released nutrients away, leaving the soil even

more impoverished.

Comparison of Where Nutrients Are Found in an

Ecosystem Based on the Averaging of Major Nutrients.

| Tropical Rainforest |

Temperate Deciduous Forest |

| 52% in Vegetation |

31% in Vegetation |

| 48% in Soil |

69% in Soil |

Common characteristics of tropical

trees

Buttress

roots:

Soils of the typical lowland rainforest are often shallow

with all the nutrients available largely remaining at surface level. Many roots stretch out

over the surface, rather than burrowing underground. Many species have broad, woody flanges at the base of

the trunk. Originally believed to help support the tree, now it is believed

that the buttresses channel stem flow and its dissolved nutrients to the

roots.

Buttress

roots:

Soils of the typical lowland rainforest are often shallow

with all the nutrients available largely remaining at surface level. Many roots stretch out

over the surface, rather than burrowing underground. Many species have broad, woody flanges at the base of

the trunk. Originally believed to help support the tree, now it is believed

that the buttresses channel stem flow and its dissolved nutrients to the

roots.

¡@

¡@

¡@

¡@

Prop and Stilt Roots:

In other places, so-called ¡§prop¡¨ or ¡§stilt¡¨ roots emerge like slanting

rods from the main trunk 1 to 2 meters above the ground to help support the

trunk. This particular kind of root is often found in flooded

or mangrove forests, where it also protects the tree against waves and currents.

They develop several aerial

pitchfork-like extensions from the trunk which grow downwards and

anchor themselves in the soil trapping sediment which helps to

stabilize the tree. Although the tree grows fairly slowly,

these above-ground roots can grow 28 inches a month.

Prop and Stilt Roots:

In other places, so-called ¡§prop¡¨ or ¡§stilt¡¨ roots emerge like slanting

rods from the main trunk 1 to 2 meters above the ground to help support the

trunk. This particular kind of root is often found in flooded

or mangrove forests, where it also protects the tree against waves and currents.

They develop several aerial

pitchfork-like extensions from the trunk which grow downwards and

anchor themselves in the soil trapping sediment which helps to

stabilize the tree. Although the tree grows fairly slowly,

these above-ground roots can grow 28 inches a month.

¡@

¡@

Drip tips:

Rainforest leaves have ¡§drip tips¡¨¡Xa

pointed shape which helps drain excess water from the leaf and reduces

vulnerability to mold and predation (to

promote transpiration). They facilitate drainage of precipitation off the leaf. They occur in the lower layers and among the saplings

of species of the emergent layer. Researchers often speak of how different

plants try to prevent ¡¨herbivory¡¨¡Xthe eating away of vegetation by insects

or other parasites¡Xand minimizing moisture with drip tips is one such

strategy. When it fails, leaves become a lacy net of holes and fibers.

Drip tips:

Rainforest leaves have ¡§drip tips¡¨¡Xa

pointed shape which helps drain excess water from the leaf and reduces

vulnerability to mold and predation (to

promote transpiration). They facilitate drainage of precipitation off the leaf. They occur in the lower layers and among the saplings

of species of the emergent layer. Researchers often speak of how different

plants try to prevent ¡¨herbivory¡¨¡Xthe eating away of vegetation by insects

or other parasites¡Xand minimizing moisture with drip tips is one such

strategy. When it fails, leaves become a lacy net of holes and fibers.

Bark: In drier, temperate deciduous forests a thick bark

( often only 1-2 mm thick, sometimes armed with spines or thorns)

helps to limit moisture evaporation from the tree's trunk. Since this is not a

concern in the high humidity of tropical rainforests, most trees have a thin,

smooth bark. The smoothness of the bark may also make it difficult for other

plants to grow on their surface. The bark of most trees looks very similar. This

similarity is very frustrating for botanist-it makes trees more difficult to

identify in the rainforest.

Mutualistic relationships:

With the constant fight for light and water, nutrients and energy, many

rainforest species come to rely on each other, and develop intimate and

exclusive relationships. Some plants, for example, provide ¡§ant houses,¡¨

home to a particular species of ant whose soldiers defend the leaves against

other would-be insect predators. Other plants provide leaves with tiny feeding

troughs, pools of sugar-solution, enticing ant patrols with sweet rewards.

Mutualistic relationships:

With the constant fight for light and water, nutrients and energy, many

rainforest species come to rely on each other, and develop intimate and

exclusive relationships. Some plants, for example, provide ¡§ant houses,¡¨

home to a particular species of ant whose soldiers defend the leaves against

other would-be insect predators. Other plants provide leaves with tiny feeding

troughs, pools of sugar-solution, enticing ant patrols with sweet rewards.

¡@

Other characteristics that distinguish tropical species of trees from those of

temperate forests include Cauliflory: the development of flowers (and hence fruits) directly

from the trunk, rather than at the tips of branches; Large fleshy fruits attract birds, mammals, and even fish as

dispersal agents.

¡@

In

every rain forest there are many kinds of plants. In fact, inside a single

hectare (2.47 acres) you can find up to 750 types of trees and 1,500 types of

plants! But this entire range of species can easily be broken down into four

categories, grouped by how they take up nutrients: Carnivorous plants eat small

animal; Saprophytic plants eat decaying matter; Parasitic plants take nutrients directly from other living

plants; Autotrophs take nutrients from the soil.

In

every rain forest there are many kinds of plants. In fact, inside a single

hectare (2.47 acres) you can find up to 750 types of trees and 1,500 types of

plants! But this entire range of species can easily be broken down into four

categories, grouped by how they take up nutrients: Carnivorous plants eat small

animal; Saprophytic plants eat decaying matter; Parasitic plants take nutrients directly from other living

plants; Autotrophs take nutrients from the soil.

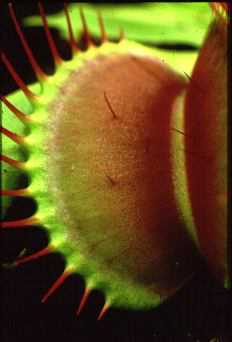

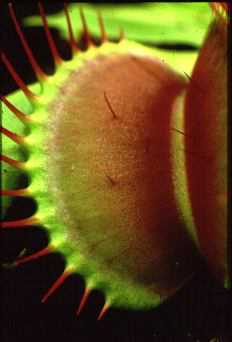

Carniverous Plants: Some plants are

adapted to obtain nutrients from animal matter. The best known of

these is probably the Venus fly trap.

The venus fly trap grows in poor soil swamps. To ensure they get enough

nitrogen they hunt insects by giving off an odor that attracts them. An

insect lands on the leaf which triggers it to snap shut. This one has

caught an insect. Venus fly traps taken and grown in other parts of the

world have even been known to eat small bits of raw ground beef. They're

obviously not picky eaters.However, more impressive is the

pitcher plant Nepenthes rafflesiana, found in southeast Asia. This

plant grows to 30 feet tall and may have pitchers 12 inches in

length, usually crammed full of digested insects. Pitcher plants also

eat small mammals and reptiles that attempt to steal the insects

from the pitcher.

Carniverous Plants: Some plants are

adapted to obtain nutrients from animal matter. The best known of

these is probably the Venus fly trap.

The venus fly trap grows in poor soil swamps. To ensure they get enough

nitrogen they hunt insects by giving off an odor that attracts them. An

insect lands on the leaf which triggers it to snap shut. This one has

caught an insect. Venus fly traps taken and grown in other parts of the

world have even been known to eat small bits of raw ground beef. They're

obviously not picky eaters.However, more impressive is the

pitcher plant Nepenthes rafflesiana, found in southeast Asia. This

plant grows to 30 feet tall and may have pitchers 12 inches in

length, usually crammed full of digested insects. Pitcher plants also

eat small mammals and reptiles that attempt to steal the insects

from the pitcher.

Saprophytes:

Many saprotrophs are

so small, called microbes, that they cannot be seen with the naked

eye. Other decomposers, which include insects, grubs, snails, slugs,

beetles and ants, aid in recycling valuable nutrients from dead

organic matter which is then released back into the soil to be

reabsorbed rapidly by plants and trees. Decayed matter contains

essential nutrients like iron, calcium, potassium and phosphorous

all of which are necessary to promote healthy rainforest growth.

Thus decomposers must work continuously to release these and other

elements into the soil. Saprophytes are the

organisms that act as the rainforests decomposers, competing with

the heavy rainfall which constantly washes away nutrients on the

forest floors. Some fungi, called mycorrhizals, are examples of

plant life that carry out this function. Decomposers work extremely

efficiently and, together with the warmth and wetness which helps

accelerate decomposition, can often break down dead animals and

vegetation within 24 hours. Decomposition in montane forests,

which are colder and less humid, however, can sometimes take up to

six weeks.

Saprophytes:

Many saprotrophs are

so small, called microbes, that they cannot be seen with the naked

eye. Other decomposers, which include insects, grubs, snails, slugs,

beetles and ants, aid in recycling valuable nutrients from dead

organic matter which is then released back into the soil to be

reabsorbed rapidly by plants and trees. Decayed matter contains

essential nutrients like iron, calcium, potassium and phosphorous

all of which are necessary to promote healthy rainforest growth.

Thus decomposers must work continuously to release these and other

elements into the soil. Saprophytes are the

organisms that act as the rainforests decomposers, competing with

the heavy rainfall which constantly washes away nutrients on the

forest floors. Some fungi, called mycorrhizals, are examples of

plant life that carry out this function. Decomposers work extremely

efficiently and, together with the warmth and wetness which helps

accelerate decomposition, can often break down dead animals and

vegetation within 24 hours. Decomposition in montane forests,

which are colder and less humid, however, can sometimes take up to

six weeks.

Growthforms

Various growthforms represent strategies to reach

sunlight:

Epiphytes: The name 'epiphyte' comes from

the Greek word 'epi' meaning 'upon' and 'phyton' meaning 'plant'. They

begin their life in the canopy from seeds or spores transported

there by birds or winds. The so-called air plants grow on the surface of other plants, especially the

trunk and branches, high in the

trees, using the limbs merely for support and extracting moisture from the

air and trapping the constant leaf-fall and wind-blown dust. Most are orchids, bromeliads, ferns, and

Philodendron relatives. Bromeliads

(pineapple family) are especially abundant in the neotropics; the orchid

family is widely distributed in all three formations of the tropical

rainforest.

Tiny plants called epiphylls, mostly mosses, liverworts and lichens, live on the

surface of leaves. As demonstration of the relative aridity of exposed branches in

the high canopy, epiphytic cacti also occur in the Americas. ( Right

picture: Cattleya sp.)

Epiphytes: The name 'epiphyte' comes from

the Greek word 'epi' meaning 'upon' and 'phyton' meaning 'plant'. They

begin their life in the canopy from seeds or spores transported

there by birds or winds. The so-called air plants grow on the surface of other plants, especially the

trunk and branches, high in the

trees, using the limbs merely for support and extracting moisture from the

air and trapping the constant leaf-fall and wind-blown dust. Most are orchids, bromeliads, ferns, and

Philodendron relatives. Bromeliads

(pineapple family) are especially abundant in the neotropics; the orchid

family is widely distributed in all three formations of the tropical

rainforest.

Tiny plants called epiphylls, mostly mosses, liverworts and lichens, live on the

surface of leaves. As demonstration of the relative aridity of exposed branches in

the high canopy, epiphytic cacti also occur in the Americas. ( Right

picture: Cattleya sp.)

Vines:

Vines are not a plant species, but a category of various forms of rainforest

vegetation that, in the words of biology professor and write John Kricher,

¡§literally tie the forest together.¡¨ These include lianas, bole climbers and

stranglers. Vines are everywhere in the rainforest and compete with other plants

for light, water and nutrients. Some, in turn, are a food source for other

creatures. They are climbing woody vines that festoon rainforest trees. Ninety per cent of

the world's vine species grow in tropical rainforests. They do this by attaching themselves to trees

with sucker roots or tendrils and growing with the young sapling, or

they climb by winding themselves round the tree's trunk. When they reach the

top of the canopy they often spread to other trees or wrap

themselves around other lianas. This network of vines gives support

against strong winds to the shallow-rooted, top-heavy trees.

However, when one tree falls several others may be pulled down also.

They have adapted to life in the rainforest by having their roots in the ground

and climbing high into the tree canopy to reach available sunlight.

Vines:

Vines are not a plant species, but a category of various forms of rainforest

vegetation that, in the words of biology professor and write John Kricher,

¡§literally tie the forest together.¡¨ These include lianas, bole climbers and

stranglers. Vines are everywhere in the rainforest and compete with other plants

for light, water and nutrients. Some, in turn, are a food source for other

creatures. They are climbing woody vines that festoon rainforest trees. Ninety per cent of

the world's vine species grow in tropical rainforests. They do this by attaching themselves to trees

with sucker roots or tendrils and growing with the young sapling, or

they climb by winding themselves round the tree's trunk. When they reach the

top of the canopy they often spread to other trees or wrap

themselves around other lianas. This network of vines gives support

against strong winds to the shallow-rooted, top-heavy trees.

However, when one tree falls several others may be pulled down also.

They have adapted to life in the rainforest by having their roots in the ground

and climbing high into the tree canopy to reach available sunlight.

Lianas

are woody vines grow rapidly up the tree trunks when there is a

temporary gap in the canopy and flower and fruit in the tree tops.

Although they begin life on the ground and their woody stems remain rooted to

the forest floor, tendrils attach to neighboring trees, and, entwined around

their host, these hitchhikers climb to the canopy on the backs of other trees.

Up in the treetops, lianas spread and a single vine can loop its way through a

number of trees. Lianas are springy and strong, able to support an adult¡¦s

weight. Some have hollow stems that contain water that can be gotten with the

aid of a machete. Lianas can weigh down a tree so much that wind and weather

collapses it more easily. A fallen liana just moves and grows on another tree.

Lianas include rattan

palms, philodendron and Strychnos toxifera (from which the deadly

poison strychnine is obtained). Rattans, the Asian lianas, have

thorny stems and can reach heights of 650 feet (200 m). They are

used to make a variety of things including baskets, ropes and wicker

furniture.

Lianas

are woody vines grow rapidly up the tree trunks when there is a

temporary gap in the canopy and flower and fruit in the tree tops.

Although they begin life on the ground and their woody stems remain rooted to

the forest floor, tendrils attach to neighboring trees, and, entwined around

their host, these hitchhikers climb to the canopy on the backs of other trees.

Up in the treetops, lianas spread and a single vine can loop its way through a

number of trees. Lianas are springy and strong, able to support an adult¡¦s

weight. Some have hollow stems that contain water that can be gotten with the

aid of a machete. Lianas can weigh down a tree so much that wind and weather

collapses it more easily. A fallen liana just moves and grows on another tree.

Lianas include rattan

palms, philodendron and Strychnos toxifera (from which the deadly

poison strychnine is obtained). Rattans, the Asian lianas, have

thorny stems and can reach heights of 650 feet (200 m). They are

used to make a variety of things including baskets, ropes and wicker

furniture.

Stranglers begin life as epiphytes in the canopy and

send their roots downward to the forest floor. The fig family is well

represented among stranglers.

These are the most aggressive vines, growing around a host tree and eventually

¡§squeezing¡¨ it to death. Stranglers have their own root system, so after

their host trees have died and decomposed, the strangler remains. It is common in the rainforest to see a mass of twisted and entwined strangler vines

fused together to form a single woody trunk that extends up towards the canopy,

now itself a host to vines. The strangler fig is a predator (hemiepyphyte).

Its seeds are deposited by bird droppings on the branch of a host tree.

The fig then sends out roots through the air until they touch the ground.

The strangler fig uses up all the host tree's water and nutrients and

eventually kills it. Most stranglers are

members of the fig family. In Spanish they are known as matapalo -

'killer tree'. When the host tree dies it leaves an

enormous upright strangler with a hollow core. By using an adult

tree as its host, the strangler fig avoids competition for

light and nutrients at ground level.

Stranglers begin life as epiphytes in the canopy and

send their roots downward to the forest floor. The fig family is well

represented among stranglers.

These are the most aggressive vines, growing around a host tree and eventually

¡§squeezing¡¨ it to death. Stranglers have their own root system, so after

their host trees have died and decomposed, the strangler remains. It is common in the rainforest to see a mass of twisted and entwined strangler vines

fused together to form a single woody trunk that extends up towards the canopy,

now itself a host to vines. The strangler fig is a predator (hemiepyphyte).

Its seeds are deposited by bird droppings on the branch of a host tree.

The fig then sends out roots through the air until they touch the ground.

The strangler fig uses up all the host tree's water and nutrients and

eventually kills it. Most stranglers are

members of the fig family. In Spanish they are known as matapalo -

'killer tree'. When the host tree dies it leaves an

enormous upright strangler with a hollow core. By using an adult

tree as its host, the strangler fig avoids competition for

light and nutrients at ground level.

Climbers: Green-stemmed plants such as philodendron that remain in

the understory. Many climbers, including the ancestors of the domesticated

yams (Africa) and sweet potatoes (South America), store nutrients in roots

and tubers.

Heterotrophs: non-photosynthetic plants can live on the forest

floor. Parasites derive their nutrients by tapping into the roots or

stems of photosynthetic species. Rafflesia

arnoldi, a root parasite of a liana, has the world's largest

flower, more than three feet in diameter. It produces an odor similar to

rotting flesh to attract pollinating insects.

List

of plants

More than two thirds of the

world plant

species are found in the tropical rainforests: plants that provide shelter and

food for rainforest animals as well as taking part in the gas exchanges which

provide much of the world oxygen supply. Rainforest plants live in a warm humid

environment that allows an enormous variation rare in more temperate climates:

some like the orchids have beautiful flowers adapted to attract the profusion of

forest insects. Competition at ground level for light and food

has lead to evolution of plants which live on the branches of other

plants, or even strangle large trees to fight for survival. The aerial plants often gather nourishment

from the air itself using so-called air roots? The humidity of the rainforest

encourages such adaptations which would be impossible in most temperate forests

with their much drier conditions.

More than two thirds of the

world plant

species are found in the tropical rainforests: plants that provide shelter and

food for rainforest animals as well as taking part in the gas exchanges which

provide much of the world oxygen supply. Rainforest plants live in a warm humid

environment that allows an enormous variation rare in more temperate climates:

some like the orchids have beautiful flowers adapted to attract the profusion of

forest insects. Competition at ground level for light and food

has lead to evolution of plants which live on the branches of other

plants, or even strangle large trees to fight for survival. The aerial plants often gather nourishment

from the air itself using so-called air roots? The humidity of the rainforest

encourages such adaptations which would be impossible in most temperate forests

with their much drier conditions. Most tropical forest soils are very poor and infertile. Millions of years of

weathering and torrential rains have washed most of the nutrients out of the

soil. More recent volcanic soils, however, can be very fertile. Tropical rain

forest soils contain less organic matter than temperate forests and most of the

available nutrients are found in the living plant and animal material.

Most tropical forest soils are very poor and infertile. Millions of years of

weathering and torrential rains have washed most of the nutrients out of the

soil. More recent volcanic soils, however, can be very fertile. Tropical rain

forest soils contain less organic matter than temperate forests and most of the

available nutrients are found in the living plant and animal material.

Buttress

roots:

Soils of the typical lowland rainforest are often shallow

with all the nutrients available largely remaining at surface level. Many roots stretch out

over the surface, rather than burrowing underground. Many species have broad, woody flanges at the base of

the trunk. Originally believed to help support the tree, now it is believed

that the buttresses channel stem flow and its dissolved nutrients to the

roots.

Buttress

roots:

Soils of the typical lowland rainforest are often shallow

with all the nutrients available largely remaining at surface level. Many roots stretch out

over the surface, rather than burrowing underground. Many species have broad, woody flanges at the base of

the trunk. Originally believed to help support the tree, now it is believed

that the buttresses channel stem flow and its dissolved nutrients to the

roots.

Prop and Stilt Roots:

In other places, so-called ¡§prop¡¨ or ¡§stilt¡¨ roots emerge like slanting

rods from the main trunk 1 to 2 meters above the ground to help support the

trunk. This particular kind of root is often found in flooded

or mangrove forests, where it also protects the tree against waves and currents.

They develop several aerial

pitchfork-like extensions from the trunk which grow downwards and

anchor themselves in the soil trapping sediment which helps to

stabilize the tree. Although the tree grows fairly slowly,

these above-ground roots can grow 28 inches a month.

Prop and Stilt Roots:

In other places, so-called ¡§prop¡¨ or ¡§stilt¡¨ roots emerge like slanting

rods from the main trunk 1 to 2 meters above the ground to help support the

trunk. This particular kind of root is often found in flooded

or mangrove forests, where it also protects the tree against waves and currents.

They develop several aerial

pitchfork-like extensions from the trunk which grow downwards and

anchor themselves in the soil trapping sediment which helps to

stabilize the tree. Although the tree grows fairly slowly,

these above-ground roots can grow 28 inches a month. Drip tips:

Rainforest leaves have ¡§drip tips¡¨¡Xa

pointed shape which helps drain excess water from the leaf and reduces

vulnerability to mold and predation (to

promote transpiration). They facilitate drainage of precipitation off the leaf. They occur in the lower layers and among the saplings

of species of the emergent layer. Researchers often speak of how different

plants try to prevent ¡¨herbivory¡¨¡Xthe eating away of vegetation by insects

or other parasites¡Xand minimizing moisture with drip tips is one such

strategy. When it fails, leaves become a lacy net of holes and fibers.

Drip tips:

Rainforest leaves have ¡§drip tips¡¨¡Xa

pointed shape which helps drain excess water from the leaf and reduces

vulnerability to mold and predation (to

promote transpiration). They facilitate drainage of precipitation off the leaf. They occur in the lower layers and among the saplings

of species of the emergent layer. Researchers often speak of how different

plants try to prevent ¡¨herbivory¡¨¡Xthe eating away of vegetation by insects

or other parasites¡Xand minimizing moisture with drip tips is one such

strategy. When it fails, leaves become a lacy net of holes and fibers.

Mutualistic relationships:

With the constant fight for light and water, nutrients and energy, many

rainforest species come to rely on each other, and develop intimate and

exclusive relationships. Some plants, for example, provide ¡§ant houses,¡¨

home to a particular species of ant whose soldiers defend the leaves against

other would-be insect predators. Other plants provide leaves with tiny feeding

troughs, pools of sugar-solution, enticing ant patrols with sweet rewards.

Mutualistic relationships:

With the constant fight for light and water, nutrients and energy, many

rainforest species come to rely on each other, and develop intimate and

exclusive relationships. Some plants, for example, provide ¡§ant houses,¡¨

home to a particular species of ant whose soldiers defend the leaves against

other would-be insect predators. Other plants provide leaves with tiny feeding

troughs, pools of sugar-solution, enticing ant patrols with sweet rewards.  In

every rain forest there are many kinds of plants. In fact, inside a single

hectare (2.47 acres) you can find up to 750 types of trees and 1,500 types of

plants! But this entire range of species can easily be broken down into four

categories, grouped by how they take up nutrients: Carnivorous plants eat small

animal; Saprophytic plants eat decaying matter; Parasitic plants take nutrients directly from other living

plants; Autotrophs take nutrients from the soil.

In

every rain forest there are many kinds of plants. In fact, inside a single

hectare (2.47 acres) you can find up to 750 types of trees and 1,500 types of

plants! But this entire range of species can easily be broken down into four

categories, grouped by how they take up nutrients: Carnivorous plants eat small

animal; Saprophytic plants eat decaying matter; Parasitic plants take nutrients directly from other living

plants; Autotrophs take nutrients from the soil. Carniverous Plants: Some plants are

adapted to obtain nutrients from animal matter. The best known of

these is probably the Venus fly trap.

The venus fly trap grows in poor soil swamps. To ensure they get enough

nitrogen they hunt insects by giving off an odor that attracts them. An

insect lands on the leaf which triggers it to snap shut. This one has

caught an insect. Venus fly traps taken and grown in other parts of the

world have even been known to eat small bits of raw ground beef. They're

obviously not picky eaters.However, more impressive is the

pitcher plant Nepenthes rafflesiana, found in southeast Asia. This

plant grows to 30 feet tall and may have pitchers 12 inches in

length, usually crammed full of digested insects. Pitcher plants also

eat small mammals and reptiles that attempt to steal the insects

from the pitcher.

Carniverous Plants: Some plants are

adapted to obtain nutrients from animal matter. The best known of

these is probably the Venus fly trap.

The venus fly trap grows in poor soil swamps. To ensure they get enough

nitrogen they hunt insects by giving off an odor that attracts them. An

insect lands on the leaf which triggers it to snap shut. This one has

caught an insect. Venus fly traps taken and grown in other parts of the

world have even been known to eat small bits of raw ground beef. They're

obviously not picky eaters.However, more impressive is the

pitcher plant Nepenthes rafflesiana, found in southeast Asia. This

plant grows to 30 feet tall and may have pitchers 12 inches in

length, usually crammed full of digested insects. Pitcher plants also

eat small mammals and reptiles that attempt to steal the insects

from the pitcher.

Saprophytes:

Many saprotrophs are

so small, called microbes, that they cannot be seen with the naked

eye. Other decomposers, which include insects, grubs, snails, slugs,

beetles and ants, aid in recycling valuable nutrients from dead

organic matter which is then released back into the soil to be

reabsorbed rapidly by plants and trees. Decayed matter contains

essential nutrients like iron, calcium, potassium and phosphorous

all of which are necessary to promote healthy rainforest growth.

Thus decomposers must work continuously to release these and other

elements into the soil. Saprophytes are the

organisms that act as the rainforests decomposers, competing with

the heavy rainfall which constantly washes away nutrients on the

forest floors. Some fungi, called mycorrhizals, are examples of

plant life that carry out this function. Decomposers work extremely

efficiently and, together with the warmth and wetness which helps

accelerate decomposition, can often break down dead animals and

vegetation within 24 hours. Decomposition in montane forests,

which are colder and less humid, however, can sometimes take up to

six weeks.

Saprophytes:

Many saprotrophs are

so small, called microbes, that they cannot be seen with the naked

eye. Other decomposers, which include insects, grubs, snails, slugs,

beetles and ants, aid in recycling valuable nutrients from dead

organic matter which is then released back into the soil to be

reabsorbed rapidly by plants and trees. Decayed matter contains

essential nutrients like iron, calcium, potassium and phosphorous

all of which are necessary to promote healthy rainforest growth.

Thus decomposers must work continuously to release these and other

elements into the soil. Saprophytes are the

organisms that act as the rainforests decomposers, competing with

the heavy rainfall which constantly washes away nutrients on the

forest floors. Some fungi, called mycorrhizals, are examples of

plant life that carry out this function. Decomposers work extremely

efficiently and, together with the warmth and wetness which helps

accelerate decomposition, can often break down dead animals and

vegetation within 24 hours. Decomposition in montane forests,

which are colder and less humid, however, can sometimes take up to

six weeks.

Epiphytes: The name 'epiphyte' comes from

the Greek word 'epi' meaning 'upon' and 'phyton' meaning 'plant'. They

begin their life in the canopy from seeds or spores transported

there by birds or winds. The so-called air plants grow on the surface of other plants, especially the

trunk and branches, high in the

trees, using the limbs merely for support and extracting moisture from the

air and trapping the constant leaf-fall and wind-blown dust. Most are orchids, bromeliads, ferns, and

Philodendron relatives. Bromeliads

(pineapple family) are especially abundant in the neotropics; the orchid

family is widely distributed in all three formations of the tropical

rainforest.

Tiny plants called epiphylls, mostly mosses, liverworts and lichens, live on the

surface of leaves. As demonstration of the relative aridity of exposed branches in

the high canopy, epiphytic cacti also occur in the Americas. ( Right

picture: Cattleya sp.)

Epiphytes: The name 'epiphyte' comes from

the Greek word 'epi' meaning 'upon' and 'phyton' meaning 'plant'. They

begin their life in the canopy from seeds or spores transported

there by birds or winds. The so-called air plants grow on the surface of other plants, especially the

trunk and branches, high in the

trees, using the limbs merely for support and extracting moisture from the

air and trapping the constant leaf-fall and wind-blown dust. Most are orchids, bromeliads, ferns, and

Philodendron relatives. Bromeliads

(pineapple family) are especially abundant in the neotropics; the orchid

family is widely distributed in all three formations of the tropical

rainforest.

Tiny plants called epiphylls, mostly mosses, liverworts and lichens, live on the

surface of leaves. As demonstration of the relative aridity of exposed branches in

the high canopy, epiphytic cacti also occur in the Americas. ( Right

picture: Cattleya sp.)

Vines:

Vines are not a plant species, but a category of various forms of rainforest

vegetation that, in the words of biology professor and write John Kricher,

¡§literally tie the forest together.¡¨ These include lianas, bole climbers and

stranglers. Vines are everywhere in the rainforest and compete with other plants

for light, water and nutrients. Some, in turn, are a food source for other

creatures. They are climbing woody vines that festoon rainforest trees. Ninety per cent of

the world's vine species grow in tropical rainforests. They do this by attaching themselves to trees

with sucker roots or tendrils and growing with the young sapling, or

they climb by winding themselves round the tree's trunk. When they reach the

top of the canopy they often spread to other trees or wrap

themselves around other lianas. This network of vines gives support

against strong winds to the shallow-rooted, top-heavy trees.

However, when one tree falls several others may be pulled down also.

They have adapted to life in the rainforest by having their roots in the ground

and climbing high into the tree canopy to reach available sunlight.

Vines:

Vines are not a plant species, but a category of various forms of rainforest

vegetation that, in the words of biology professor and write John Kricher,

¡§literally tie the forest together.¡¨ These include lianas, bole climbers and

stranglers. Vines are everywhere in the rainforest and compete with other plants

for light, water and nutrients. Some, in turn, are a food source for other

creatures. They are climbing woody vines that festoon rainforest trees. Ninety per cent of

the world's vine species grow in tropical rainforests. They do this by attaching themselves to trees

with sucker roots or tendrils and growing with the young sapling, or

they climb by winding themselves round the tree's trunk. When they reach the

top of the canopy they often spread to other trees or wrap

themselves around other lianas. This network of vines gives support

against strong winds to the shallow-rooted, top-heavy trees.

However, when one tree falls several others may be pulled down also.

They have adapted to life in the rainforest by having their roots in the ground

and climbing high into the tree canopy to reach available sunlight.

Lianas

are woody vines grow rapidly up the tree trunks when there is a

temporary gap in the canopy and flower and fruit in the tree tops.

Although they begin life on the ground and their woody stems remain rooted to

the forest floor, tendrils attach to neighboring trees, and, entwined around

their host, these hitchhikers climb to the canopy on the backs of other trees.

Up in the treetops, lianas spread and a single vine can loop its way through a

number of trees. Lianas are springy and strong, able to support an adult¡¦s

weight. Some have hollow stems that contain water that can be gotten with the

aid of a machete. Lianas can weigh down a tree so much that wind and weather

collapses it more easily. A fallen liana just moves and grows on another tree.

Lianas include rattan

palms, philodendron and Strychnos toxifera (from which the deadly

poison strychnine is obtained). Rattans, the Asian lianas, have

thorny stems and can reach heights of 650 feet (200 m). They are

used to make a variety of things including baskets, ropes and wicker

furniture.

Lianas

are woody vines grow rapidly up the tree trunks when there is a

temporary gap in the canopy and flower and fruit in the tree tops.

Although they begin life on the ground and their woody stems remain rooted to

the forest floor, tendrils attach to neighboring trees, and, entwined around

their host, these hitchhikers climb to the canopy on the backs of other trees.

Up in the treetops, lianas spread and a single vine can loop its way through a

number of trees. Lianas are springy and strong, able to support an adult¡¦s

weight. Some have hollow stems that contain water that can be gotten with the

aid of a machete. Lianas can weigh down a tree so much that wind and weather

collapses it more easily. A fallen liana just moves and grows on another tree.

Lianas include rattan

palms, philodendron and Strychnos toxifera (from which the deadly

poison strychnine is obtained). Rattans, the Asian lianas, have

thorny stems and can reach heights of 650 feet (200 m). They are

used to make a variety of things including baskets, ropes and wicker

furniture. Stranglers begin life as epiphytes in the canopy and

send their roots downward to the forest floor. The fig family is well

represented among stranglers.

These are the most aggressive vines, growing around a host tree and eventually

¡§squeezing¡¨ it to death. Stranglers have their own root system, so after

their host trees have died and decomposed, the strangler remains. It is common in the rainforest to see a mass of twisted and entwined strangler vines

fused together to form a single woody trunk that extends up towards the canopy,

now itself a host to vines. The strangler fig is a predator (hemiepyphyte).

Its seeds are deposited by bird droppings on the branch of a host tree.

The fig then sends out roots through the air until they touch the ground.

The strangler fig uses up all the host tree's water and nutrients and

eventually kills it. Most stranglers are

members of the fig family. In Spanish they are known as matapalo -

'killer tree'. When the host tree dies it leaves an

enormous upright strangler with a hollow core. By using an adult

tree as its host, the strangler fig avoids competition for

light and nutrients at ground level.

Stranglers begin life as epiphytes in the canopy and

send their roots downward to the forest floor. The fig family is well

represented among stranglers.

These are the most aggressive vines, growing around a host tree and eventually

¡§squeezing¡¨ it to death. Stranglers have their own root system, so after

their host trees have died and decomposed, the strangler remains. It is common in the rainforest to see a mass of twisted and entwined strangler vines

fused together to form a single woody trunk that extends up towards the canopy,

now itself a host to vines. The strangler fig is a predator (hemiepyphyte).

Its seeds are deposited by bird droppings on the branch of a host tree.

The fig then sends out roots through the air until they touch the ground.

The strangler fig uses up all the host tree's water and nutrients and

eventually kills it. Most stranglers are

members of the fig family. In Spanish they are known as matapalo -

'killer tree'. When the host tree dies it leaves an

enormous upright strangler with a hollow core. By using an adult

tree as its host, the strangler fig avoids competition for

light and nutrients at ground level.