The original nationality of the name of Granger is unmistakeable. Arthur, in his "Derivation of Family Names," it is true, says that it is of Saxon origin, but this is unquestionably a mistake. Its very termination, er, places it at once in the catalogue of names introduced into Britain by the followers of William the Conqueror, or by those coming later from France. "The French names introduced at the conquest may be generally known by the prefixes or suffixes, er, etc." -- Somers' "Family Nomenclature," page 52. It does not appear in English history prior to A. D. 1066; the names of W. de Grangers and S. de Grangers being found in Fox's copy (?) of the "Roll of Battle Abbey." Assuming this copy to be correct, this is the earliest record which can be found of the name of Grange, Granger, Grangers, Grainger, or Graunger in English history.

The word grange is clearly French, in ancient as well as modern use. Its primary meaning

in Normandy and other parts of France was a granary or barn where grain was stored. Even

now in modern French, its meaning is the same, while granger means, "one who holds a farm on

condition of dividing with the proprietor the products of the soil;"(*) that is, paying his

rent by dividing his crop with his landlord. Upon the first introduction of the word grange

into England, it was applied to the farmhouse or homestead of the outlying fields or manor of

some Abbey or Priory, and the bailiff who presided over one was called Ate Grange, and afterwards,

Granger; that is, the man who had charge of a farm belonging to an Abbey or some great landlord

either as tenant or servant, was called a Granger.

(*) Little's Dict. Langue Francaise

As the word grange became anglicized, its application and meaning was enlarged, and it denoted also a tract of land on which grain was grown, or a large farm. The Grange would be distinguished from the castles and halls where the barons resided with their immediate attendants, and was applied to those outlying fields and tenements where resided the peasants and menial servitors who were engaged in tilling the soil. In Dauphin‚, a farmer is still called a granger, and in France the grange is still a "part" of an estate.

At the time of the Conquest, neither in France nor England had surnames been adopted by any but the leading families. Indeed, although it is claimed by some that they were in use among the Anglo-Saxons, the proof is not clear, but in Normandy the names of their estates had been to a certain extent adopted by families of distinction. This name so taken, was not, however, always hereditary, but the practice had commenced, and grew with some speed. With the Conquest, the custom was introduced into England, and those who held lands there commenced to assume the name either of the place in Normandy from whence they came, or that in which they had settled. But for generations, whatever was done toward assuming hereditary names was confined to the upper classes, and hardly before the thirteenth century did it even begin to prevail among others. Only as the people began to rise gradually from the depths of serfdom, did the giving of surnames extend down through the social scale. Commoners, as well as peasants, were for hundreds of years known by a Christian name only, and if it was necessary to distinguish one John from another John, or one Francois from another Francois, some name connected with their residence, calling, or surrounding circumstances, was given by common consent. John the German, Phillip of Neuville, Peter the smith, would designate the nationality, place of birth, or trade of the man, sufficiently to distinguish him from others of the same name.

Many surnames appear, as I have said, in the thirteenth century, but confined almost exclusively to the upper classes. As late as 1381, they were not general among the lower classes, and the man who that year headed the famous uprising in London, and is known in history as Wat Tyler, was called Wat (Walter) the Tyler (Slater) from his trade. In 1406 a man describes himself as John the son of William the son of John de Hunshelf, and ten years later appears as John Wilson. The Rev. Mark Noble(*) says that "it was late in the Seventeenth century that many families in Yorkshire, even of the more opulent sort, took stationary names," and in the present century a man, whose father's name was Johnson, becoming a pig-dealer, called himself John Pigman, and placed that name over his shop door. To this day, the miners in England do not, in most cases, know a family name, but are called by wife, children, friends and all, by some nickname, such as Nosey, Soaker, Bulleyed, etc.

It will be seen, then, that those men whose names appear in the early centuries, as W. de Granger, S. de Granger, Roger de la Grange, Richard le Granger, Jordan de la Grange, etc., were not necessarily blood kinsmen, or allied, save in occupation. They were possibly servants or laborers of higher or lower degree, for some great landowner about his barns and granaries, and later upon his farms. The lands were, of course, held by great families, who each owned many farms, and the name of Granger would not apply to them, but to their employes. The family, therefore, cannot be said to be of high or noble origin, but probably sprung from the middle or lower class of France or England. Indeed to this day, the name is not found among those families who appear in Burke's "History of the Landed Gentry" but enough does appear to show that at present the name is found either as Grainger, Granger, or le Grange among the best of the middle classes of Great Britain.

In England, in the earlier centuries, the French article a, the particle le (the) or de le

(of the) were prefixed to the names simply as descriptive of the person. As has been shown,

Roger-who-worked-at-the barn, would be the meaning of Roger de la Granger, and John

(*) Hist. Coll. Names, 29.

Graunger or Richard le Granger would mean John the farmer, or Richard the barnman. But as the influence of the Saxon tongue was felt upon the imported French names, the particles began to be dropped, and about the time of Henry the Sixth, they rapidly disappeared, with the adoption of hereditary family names and the use of the title Esquire by the heads of families, and Generosus by the sons. Children then began to take the names of their fathers; John de la Grange became John Granger, and his offspring, Granger's. Corruption of the French word Grange crept in, as was natural, in England, and became Graunge, as we see in the Pious Plowman, which, describing the Good Samaritan, says:

"His wounds he washed,

Embawmed hym and bound his head,

And ledde hym forth on Lyard

To "Lex Christi" a graunge

Wel sixe or sevene

Beside the newe market."

So the corruption of the name into Graunger naturally followed, as the letter "u" was

frequently introduced into words by the Saxons.

Again, the connection of the barn or farm with grain, produced sometimes a spelling of the name as Grainger, which exists to this day, and grange is still spelled grainge in Burgundy. The two families Granger and Grainger still keep the spelling distinct and each has a different coat of arms and crest. And to the workmen themselves the same change in spelling is applied, for we find in Henry Best's "Farming Book" (A. D. 1641) the following:

"His tenants, the graingers, are tyed to come themselves, and winde the woll; they have a fatte weather, and a fatte lambe killed, and a dinner provided for their paines."

The word graingers, it clearly appears, was here distinctly applied to the laborers upon a farm; in this case a sheep farm, as they were to "winde the woll" (wool) and they were "tenants" of the owner of the farm.

I have often been informed by members of the family that the name appears upon the Roll of Battle Abbey, and this has been claimed by some of my enthusiastic relatives as unmistakable evidence of the antiquity of our line. I have already shown that surnames were not hereditary at the time of the Conquest, but a brief sketch of the famous Roll will not be inappropriate here. Readers should also remember that "The unsettled state of surnames in those early times renders it difficult to trace the pedigree of any family beyond the thirteenth century."--Lower's "Family Nomenclature."

The Battle of Hastings was fought 14 Oct., 1066. Tradition says that, on the morning after, Odo, Bishop of Bayeux (Baiux), sung Mass, and then the Duke ordered his clerk to call the roll of his warriors to learn who had fallen in the struggle. He then ordered a monastery to be erected upon the site of the struggle, which was called Battle Abbey, and to the monks he entrusted the engrossing of the names of all his principal soldiers who had survived the fight. This they proceeded to do, and the roll was hung upon the walls of Battle Abbey to preserve to posterity the names of those who won the great victory.

How long the Roll hung upon the walls of the famous abbey is a matter of conjecture, and no definite trace of its future history remains. We know that Henry the Eighth granted the abbey and its appurtenances to Sir Anthony Browne, ancestor of the Viscounts Montague, but this family sold the mansion to Sir Thomas Webster, Bart, and removed to Cowdray House, near Midhurst. It is strongly suspected that to this latter place the famous document was carried. Cowdray House was afterwards burnt with all its contents, and possibly the most valued list of names in the world was then destroyed.

There are six or more so-called copies of the Roll, which have come down from earlier times, but they must all be received with great suspicion. Not but what they contain many names which were undoubtedly upon the original Roll, but it is certain that many have been added since the year of the battle. Sir William Dugdale openly accuses the Monks of Battle of having inserted the names of persons whose ancestors were never at the Conquest, moved, undoubtedly, by flattery or bribes. The lists differ greatly; names appear in some which are not found in others. Spelling is different, and in one only (Foxe's) does the initial or Christian name appear.

Preference is usually given to the list prepared by John Leland, both because it shows more marks of correctness, and because he is the only transcriber who saw the original Roll. In this the name of Granger does not appear, nor does it in Hollingshead's copy, in which appear the names of over six hundred persons. But in that known as "Foxe's Copy" appear the names of W. de Grangers and S. de Grangers, and upon this some hang their misty claim to a connection with the Conquerors.

But Foxe's copy is the most unauthentic of all. It appears in his "Acts and Monuments." He never saw the Roll itself, and confesses that he "took it out of the Annals of Normandy, in French, whereof one very ancient written booke in parchment remaineth in the custody of the writer himself." He divides the names into three lists: 1st. Those who were evidently of the highest rank. 2d. The Archers of Val du Real and many other places, and 3d, Other names "out of the ancient chronicles of England, touching the names of other Normans which remain alive after the Battle, and to be advanced to the Seignories of this land." In this list, so wanting in evidences of authenticity, so unreliable on its face, admittedly taken from an old French manuscript, we base our claim that two by the name of Granger came over with William the Conqueror.

I have said sufficient to show how difficult it would be, under the most favorable circumstances, to trace the family, or any family, back to the twelfth or thirteenth century. We should undoubtedly meet the fact that our fathers did not then take the surname of theirs, and find many Grangers allied, not by blood, but by occupation. Proof would meet us of the truth of the saying by a well-known writer, "Our actual names are the Christian ones; the surnames have sprung up in consequence of the inadequacy of them to distinguish the increasing number of individuals."

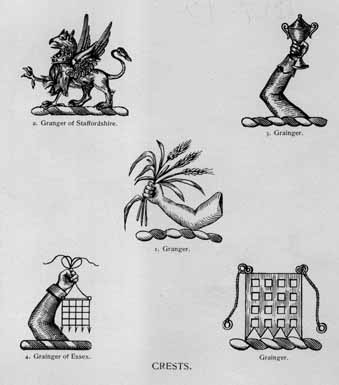

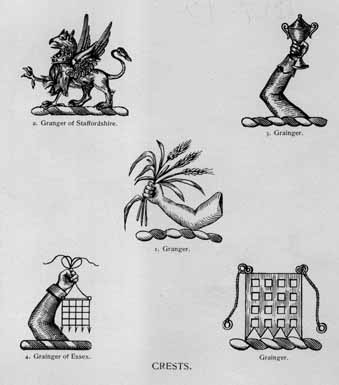

There is no crest or coat-of-arms of the Grangers, which, as far as I can learn, the descendants of Launcelot have a clear title to. There are several crests which have belonged to families of the same name as ours, but it does not by any means follow that Launcelot had a right to any of them. A few words in explanation will assist in making clear this statement.

Crests were originally an ornament worn on the top of a helmet by a knight in armor, so that he, while his face was covered with his metal vizor, could be distinguished and known in battle. These crests were generally the design of a bird, animal, or part of a man, such as a leg, an arm, or hand. Afterwards the "Arms" were displayed upon the shield which the knight carried, or were embroidered on the tunic or "camise" which was worn over the armor. These arms served the same purpose as the crest. When the necessity which first caused their use disappeared before the advent of gunpowder, the crest and arms were retained by the descendants of those who had borne them in battle, as a matter of family pride. At first the crest and arms were selected by each knight according to his own fancy, and were not hereditary, but eventually they were granted by the Sovereign, who appointed the Heralds to have charge of the records of the arms. Severe laws were enacted, now repealed, forbidding the use of the crest or arms by any unauthorized person. At present the Garter King at Arms is the head of the English College of Heralds, the Lyon King of the Scottish College, and the Ulster King of the Irish one. The crest and arms of the person to whom they were granted descended intact to his eldest son, while the younger sons were required to make a "difference" in the arms. They thus became strictly hereditary, passing down from father to son in the direct male line. If arms had been granted to Launcelot's father, or if he had inherited them, Launcelot himself would have been entitled to bear them, but if they had been granted to Launcelot's uncle, instead of his father, they would not have descended to us.

It will be seen, then, that, before we can claim arms or a crest, we must show that our ancestors had an undisputed title to them, either by grant or inheritance, and it is not sufficient to show that some family named Granger had a right at one time to bear them. All Smiths do not come from the same ancestor Smith; all Grangers can make no better claim to be descended from a common Granger. One writer truly says: "To strike at the root of the evil, it is necessary to state explicitly that there is no such thing as a coat-of-arms belonging to the bearer of any particular surname. Identity of name does not argue identity of origin."

Many of the emigrants to New England were gentlemen of distinction and family, and brought with them their arms, which have been carefully preserved by their descendants, and are therefore authentic. Other New England families have traced their line back to their old home, and connected themselves with some ancestor there who had a clear title to a crest and armorial bearings. But diligent search has failed to discover any coat-of-arms of Launcelot, and, until we connect him with his English family, there is no hope of our obtaining a just and indefeasible title to the insignia which so many people prize. Most of the American families find themselves in a like position as ourselves, but that does not deter many from flaunting a crest and arms. "The ordinary mode of assuming armorial bearings (in America) has been a reference to the nearest seal or card engraver, who, from an heraldic encyclopedia has furnished the applicant with the arms of any family of the same name." Probably not one out of a hundred of those families in this country, who claim to have coats-of-arms, have a shadow of title to the same. It is reported that a European ambassador at Washington, having sent his carriage to the repair shop, called one day to see how the work was progressing. He was surprised to see his coat-of-arms, which graced the panel of the door of his coach, reproduced upon half a dozen other carriages in the shop which did not belong to him. In answer to his indignant protests, the carriage-maker explained that some of his customers had thought the arms "real pretty," and at their request he had obligingly painted it upon their panels also.

There are several crests known to have belonged to different branches of the Granger family. The most common is figure one (1), and is described in the language of heraldry "a dexter arm, couped and embowed, in hand three wheat ears. all ppr." It cannot be found to what particular branch this crest belongs; it is simply recorded as the crest "of the Grangers," and is, perhaps, the safest to use, if one wishes a crest.

On an old deed in Tettenhall, in Staffordshire, appears the crest of the "Grangers of Staffordshire," and is shown in figure two (2). It is described as "a griffin passant (without gorging)." The griffin was an emblem of vigilance, and inhabited the mountains of Bactria, where he guarded an immense treasure of gold.

The Graingers also had many crests. One family of that name bore the one shown in figure three (3), and it is described "A dexter arm couped, az, purfled or, cupped ar in hand, all ppr." A family of Graingers in Essex had as a crest a dexter arm bearing a portcullis, as shown in figure four (4). Still another had the portcullis alone, figure five (5).

A woman cannot, under any circumstances, bear a crest (though she may bear arms), unless she is a sovereign princess, but in this country we are all sovereigns.

The motto of all the Grangers is "Honestas optima politia" (Honesty is the best policy).

During later years, indeed, within this century, the pronunciation of the family name has changed in most parts of the country. Almost universally it is now pronounced as though it were spelt GRAIN-ger. Up to fifty years ago, it was always spoken as it is spelt, for the present pronunciation is certainly not correct, save so far as modern custom makes it so. The old pronunciation gave the first syllable the sound of gran, in gran-ny, gran-ite, gran-ulate, etc. It would certainly sound strange, and, possibly, unpleasant to the modern ear, if the name should now be spoken as in the olden time, but it would be sanctioned both by the ancient custom and phonetic rules. Yet to this day, in Boston and certain parts of Eastern New England, the former pronunciation prevails, and I have there been sometimes addressed in the old style.

The meaning of the name Launcelot is "A little angel."