|

|

3.1 Introduction

Innumerable stories and even more rumours exist about the mysterious powers of pollen and its nutritional value. Pollen is frequently called the "only perfectly complete food". High performance athletes are quoted as eating pollen, suggesting their performance is due to this "miracle food", just as the "busy bee" represents a role model for an active and productive member of society. Using suggestive names, labels and descriptions in marketing of various products containing pollen sometimes reach almost fraudulent dimensions, creating false hopes and expectations in people, often connected with high prices of the product. Such practices are untruthful, unethical and should be avoided.

It is however, often difficult for a lay person to verify the numerous claims, particularly those backed up with so-called reports from "doctors". Conversely, it does not always take a "scientific" study to prove that a food (or substance of herbal origin) has a medicinal or otherwise beneficial effect. Many times, modern science is not willing or able to prove beneficial effects according to its own rigid standards, methods and technologies. However, as a whole, caution should be exercised in accepting the many claims made to the credit of pollen and for that matter also for the other products incorporating products from the bee hive.

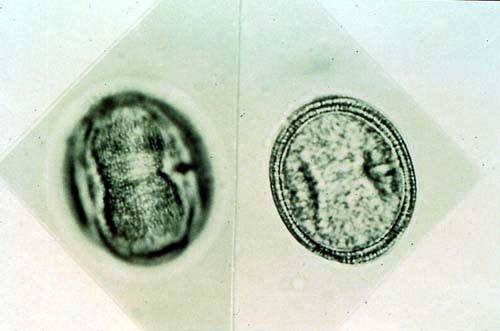

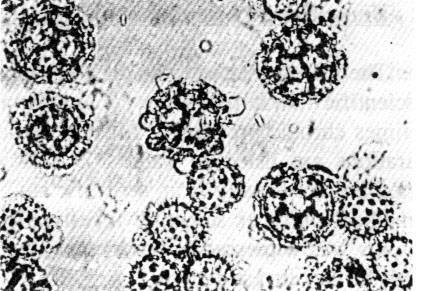

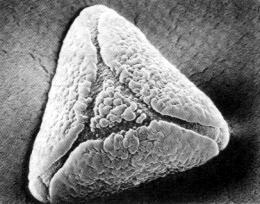

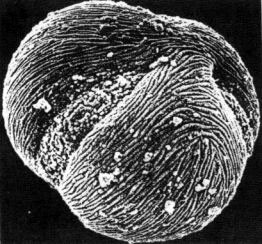

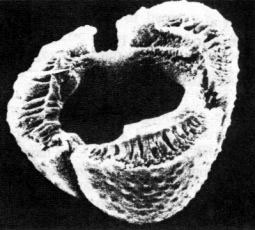

Pollen grains are small, male reproduction units (gametophytes) formed in the anthers of the higher flowering plants (see Figure 3.1). The pollen is transferred onto the stigma of a flower (a process called pollination) by either wind, water or various animals (mostly insects), among which bees (almost 30,000 different species) are the most important ones.

Each pollen grain carries a variety of nutrients and upon arrival at the stigma it divides into several cells and grows a tube through the often very long stigma of the flower. Growth continues to the embryo sac in the ovarium of the flower, inside which one egg cell will fuse with a sperm cell from the pollen and complete the fertilization. Depending on the requirements for this process and the mode of transport from one flower to the next, i.e. insects, water or wind, each species of plants has evolved a characteristic pollen type. Thus, the pollen grains from most species can be distinguished by their outer form and/or by their chemical composition or content of nutrients. The knowledge of this is used in the identification of paleontological discoveries (paleopalynology) and in the identification of geographic and botanical origin of honeys (melissopalynology).

To determine the value of pollen as a supplementary food or medicine, it is important to know that pollen from each species is different and no one pollen type can contain all the characteristics ascribed to "pollen" in general. Therefore, in this text, pollen will always refer to a mixture of pollen from different species, unless otherwise mentioned. A logical conclusion is that pollen from one country or ecologic habitat is always different from that of another. People who are allergic to pollen will have noticed this during their travels.

|

|

For those who see in nature something more than just the mechanical and

chemical interactions of substances and organisms, it might be added

that flowers form a very special part of plants. They carry special

"energies" which are used in traditional alternative medicinal

practices such as therapies with Bach flowers, aroma therapy or the use

of numerous herbal teas. Such energies may well be carried by certain

chemical substances other than water, but this is not necessarily the

case, as for example, homeopathic preparations demonstrate.

Since pollen is a part of these flowers and in addition is or represents the male reproductive portion, it also has very special "energies" or values of its own. In a wider understanding in certain philosophical environments, special plant and pollen surface structures interact with cosmic energies and may acquire some of their characteristics by this means.

Apart from these less orthodox explanations, certain empirical results have in the past been described for the effects of pollen on humans and animals. These will be discussed under medicinal uses. As far as the miracle food aspect of pollen is concerned, the diversity of pollen must be emphasized again and the fact that some pollen types (i.e., pine and eucalyptus) are nutritionally insufficient even for the raising of honeybee larvae. In an excellent review, Schmidt and Buchmann (1992) compared the average protein, fat, mineral and vitamin content of pollen with other basic foods. Pollen was richer in most ingredients when compared on a weight or calorie content basis than such foods as beef, fried chicken, baked beans, whole wheat bread, apple, raw cabbage and tomatoes. While comparable in protein and mineral content with beef and beans, Pollen averages more than ten times the thiamin and riboflavin or several times the niacin content. Pollen is usually consumed in such small quantities that the daily requirements of vitamins, proteins and minerals cannot be taken up through the consumption of pollen alone. However, it can be a substantial source of essential nutrients where dietary uptake is chronically insufficient.

If the nutritional benefit of pollen in small dosages is accepted, as described in many non-scientific publications, it must be understood as a synergistic effect. That is, a wide variety of beneficial substances interact to improve absorbtion or use of the nutrients made available to the body from regular nutrition. Pollen nutrients may also balance some deficiencies from otherwise incomplete or unbalanced supplies, absorption or usage.

The pollen which is collected by beekeepers and used in various food or medicinal preparations is no longer exactly the same as the fine, powdery pollen from flowers. The hundreds or sometimes millions of pollen grains per flower are collected by the honeybees and packed into pollen pellets on their hind legs with the help of special combs and hairs (see Figure 3.2). During a pollen collecting trip, one honeybee can only carry two of these pollen pellets.

The pollen collected by honeybees is usually mixed with nectar or regurgitated honey in order to make it stick together and adhere to their hind legs. The resulting pollen pellets harvested from a bee colony are therefore usually sweet in taste. Certain pollen types however, are very rich in oils and stick together without nectar or honey. A foraging honeybee rarely collects both pollen and nectar from more than one species of flowers during one trip. Thus the resulting pollen pellet on its hind leg contains only one or very few pollen species. Accordingly, the pollen pellet has a typical colour, most frequently yellow, but red, purple, green, orange and a variety of other colours occur (see Figure 3.3).

The partially fermented pollen mixture stored in the honeybee combs, also referred to as "beebread" has a different composition and nutritional value than the field collected pollen pellets and is the food given to honeybee larvae and eaten by young worker bees to produce royal jelly. Saying pollen is the perfect food because it is the only food source for honeybees other than honey, their major carbohydrate source is not only based on a questionable comparison between human needs and bee requirements, but also on plain misinformation.

a) |

b) |

|

Figure 3.2: a) A honeybee forager collecting pollen from a composite flower. The pollen grains caught in the specially branched hairs of honeybees are brushed off with the legs, moistened with nectar or honey and compacted in the pollen pellets on the outside of the hind legs (photo courtesy of F. Intoppa). b) A scanning electron microscopic enlargement of the hind leg of a honeybee with the pollen pellet on the outside (photo courtesy of R.C. Davis). The bottom section of the leg consists of the pollen brush. The joint between the leg segments serves to compact the pollen and push it to the outside, thus forming the typical pollen pellet. |

|

Pollen grains range from 6 to 200 m m in diameter, and all kinds of colours, shapes and surface structures may be observed. These are usually typical enough to allow species or at least genus identification (see Figures 3.3 and 3.4). Most pollen grains have a very hard outer shell (sporoderm) which is very difficult or impossible to digest. It is so durable that it can be found in fossil deposits millions of years old. There are, however, pores which allow germination and also extraction of the interior substances.

3.3 The composition of pollen

Since the composition of pollen changes from species to species, variation in absolute amounts of the different compounds can be very high. Protein contents of above 40% have been reported, but the typical range is 7.5 to 35%: typical sugar content ranges from 15 to 50% and starch content is very high (up to 18%) in some wind-pollinated grasses (Schmidt and Buchmann, 1992). Composition of pollen and bee-collected pollen however, has to be distinguished. Some average values for bee-collected pollen are shown in Table 3.1.

|

|

The major components are proteins and amino acid, lipids (fats, oils or

their derivatives) and sugars. The minor components are more diverse

(Table 3.2). All amino acids essential to humans (phenylalanine,

leucine, valine, isoleucine, arginine, histidine, lysine, methionine,

threonine and tryptophan) can be found in pollen and most others as

well, with proline being the most abundant. Many enzymes (proteins) are

also present but some, like glucose oxidase which is very important in

honey. have been added by the bees. This enzyme is therefore more

abundant in "beebread" than in fresh pollen pellets.

Only 16 of the 31 fatty acids found in pollen had been identified by 1989 (Shawer et al. 1987 and Muniategui et al., 1989). Palmitic acid is the most important one, followed by myristic, linoleic, oleic, linolenic, stearic acids etc. Simal et al., (1988) list 7 sterols, including cholesterol. Mono-, di- and triglycerides are fairly abundant, too.

Most simple sugars in pollen pellets such as fructose, glucose and sucrose come from the nectar or honey of the field forager. The polysaccharides like callose, pectin, cellulose, lignin sporopollenin and others are predominantly pollen components. After storage in the comb the further addition of sugars and enzymes creates beebread, through lactic acid fermentation.

Table 3.1:

The average composition of dried pollen

|

Bee-collected |

Hand-collected |

||

|

%a |

%b |

%b |

|

| Water (air-dried-pollen) |

7 |

11 |

10 |

| Crude protein |

20 |

21 |

20 |

| Ash |

3 |

3 |

4 |

| Ether extracts (crude fat) |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Carbohydrate | |||

| Reducing sugars |

36 |

26 |

3 |

| Non-reducing sugars |

1 |

3 |

8 |

| Starch |

- |

3 |

8 |

| Undetermined |

28 |

29 |

43 |

a As reported by Tabio et al., 1988

b As reported by Crane, 1990

Table 3.2:

Minor components of bee collected pollen (Crane, 1990)

| Flavonoids | At least 8 (flavonoid pattern is characteristic for each pollen type) |

| Carotenoids | At least 11 |

| Vitamins | C, E, B complex (including, niacin, biotin, pantothenic acid, riboflavin (B2), and pyridoxine (B6)). |

| Minerals | Principal minerals: K, Na, Ca, Mg, P, S. Trace elements: A1, B, C1, Cu, I, Fe, Mn, Ni, Si, Ti and Zn |

| Terpenes | |

| Free animo acids | All |

| Nucleic acids and nucleosides | DNA, RNA and others |

| Enzymes | More than 100 |

| Growth regulators | Auxins, brassins, gibberellines, kinins and growth inhibitors |

| a) Anarcadium sp. From honey in Guyana | |

|

|

| b) Vernonia perotteti gr. (large) and Synedrella gr (small, spiny) from honey in Malawi | |

|

|

| c) Eucalyptus camaldulensis, light microscope | |

|

|

|

d) Eucalyptus sp., scanning electron microscope (SEM) |

|

|

|

| e) Acerplantanoides (SEM, approx. 2600x) | |

|

|

| f) Centaurea cyanus (freeze sectioned, SEM approx 2400x) showing thick pollen wall) | |

|

|

|

Figure 3.4: Pollen grains of various

species. Photos courtesy of (a) L. Persano Oddo; (b and c) G.

Ricciardelli d'Albore from Persano Oddo et al., (1988); (d) F. Intoppa;

(e and f) S. Nilsson from Nilsson et al., (1977).

|

3.4 The physiological effects of pollen

3.4.1 Unconfirmed circumstantial evidence

The effects and benefits derived from pollen consumption, according to some of the non-scientific literature on the subject are endless. Many people report improvement of sometimes chronic problems. Most of the major ailments reported to improve with pollen preparations are listed in Table 3.3. However, one should be aware that the benefits reported are not usually from scientific studies but are merely personal experiences without any medical or other scientific investigation of claims. Sometimes the disappearance of symptoms was witnessed by physicians, but the reasons for such cures were not confirmed through further investigations.

Table 3.3:

Non-scientific claims and reports of benefits, cures or improvements

derived

from the use or consumption of bee-collected pollen.

|

Improvements |

Cures of benefits |

| Athletic preformance | Cancer in animals |

| Digestive assimilation | Colds |

| Rejuvenation | Acne |

| General vitality | Male sterilitya |

| Skin vitality | Anaemiab |

| Appetiteb | High blood pressureb |

| Haemoglobin contentb | Nervous and endocrine disordersb |

| Sexual prowess | Ulcers |

| Performances (of a race horse) |

a Ridi et al., 1960

b Sharma and Singh, 1980

3.4.2 Scientific evidence

The only long-term observations on the medicinal effect of pollen are related to prostate problems and allergies. Several decades of observations in Western European countries and a few clinical tests have shown pollen to be effective in treating prostate problems ranging from infections and swelling to cancer (Denis, 1966 and Ask-Upmark, 1967).

Supplementation of animal diets with pollen has shown positive weight gain and other beneficial effects for piglets, calves, broiler chickens and laboratory cultures of insect (see 3.5.2).

Certain bacteriostatic effects have been demonstrated (Chauvin et al, 1952) but this is attributed to the addition of glucose oxidase (the same enzyme responsible for most antibacterial action in honey) by the honeybee when it mixes regurgitated honey or nectar with the pollen (Dustmann and Gunst, 1982). Therefore, this activity varies between pollen pellets and is much higher in beebread. A very slight antibacterial effect can also be detected in pollen collected by hand (Lavie, 1968).

There is some evidence that ingested pollen can protect animals as well as humans against the adverse effects of x-ray radiation treatments (Wang et al., 1984; Hernuss et al., 1975, as cited in Schmidt and Buchmann, 1992).

3.5 The uses of pollen today

3.5.1 As medicine

In order to desensitize allergic patients, pollen is usually collected directly from the plants, to allow proper identification and purity. A pollen extract is then injected subcutaneously. Desensitization through ingestion of pollen is claimed, but has not received any scientific confirmation.

For treatment of various prostate problems, pollen is usually prescribed in its dry pellet form as collected by the bees. Pollen from different countries or regions seems to work equally well. However, pollen has not been officially recognized as a medicinal drug.

Since the consumption of pollen appears to improve the general condition and food conversion rate in animals as well as people, its support in accompanying other cures should be solicited more frequently. There may be other medicinal uses in traditional medicine which, however, have not been published in readily accessible journals.

3.5.2 As food

The major use of pollen today is as a food or, more correctly, as a food supplement (see Figure 3.5). As stated earlier its likely value as a food for humans is frequently overstated and has never been proven in controlled experiments. That it is not a perfect food, as stated on many advertisements, food packages and even in various non-scientific publications should be obvious. Its low content or absence of the fat soluble vitamins should be sufficient scientific evidence. This does not mean that its consumption may not be beneficial, as has been shown scientifically with various animal diets.

Pollen has been added to diets for domestic animals and laboratory insects resulting in improvements of health, growth and food conversion rates (Crane, 1990; Schmidt and Buchmann, 1992). Chickens exhibited improved food conversion efficiency with the addition of only 2.5% pollen to a balanced diet (Costantini & Ricciardelli d'Albore, 1971) as did piglets (Salajan, 1970). Beekeepers too, feed their colonies with pure pollen, pollen supplements or pollen substitutes (see 3.11.6) during periods with limited natural pollen sources. The relatively high cost of pollen suggests the need for a detailed feasibility analysis of pollen as food additive or supplement.

Only a good mixture of different species of pollen can provide the average values mentioned in the tables describing the composition of pollen. The real value of diversity of pollen content, however, lies in the balance of these nutrients and the synergistic effect of the diversity as well as more subtle effects or characteristics related to their origin rather than their quantitative presence. Those very subtle characteristics and sensitive compounds are easily lost with improper storage and processing, something to carefully watch when making or buying quality products containing "bee" pollen.

The stimulative effect of pollen and its possible improvement of food conversion in humans as well as animals, should be of particular interest to those who have an unbalanced or deficient diet. There are no hard scientific data to back up this information, but a detailed study might show tremendous potential benefit to a very large portion of human society. The only serious problem with incorporating pollen in foods like candy bars, sweets, desserts, breakfast cereals, tablets and even honey is the widespread allergic susceptibility of people to pollen from a wide variety of species (see 3.10).

Beebread

Traditional beekeeping cultures with honeybees or stingless bees, usually appreciate the stored pollen, i.e. beebread (see Figure 3.6). Its characteristic sour taste together with brood and honey is a delicacy consumed directly during harvesting. The pollen stored by honeybees undergoes a lactic acid fermentation and is thus preserved. This final storage product is called beebread. As also mentioned in Chapter 8, these beebread combs may be sold directly but a recipe in 3.12.2 describes the preparation of fermented pollen in a similar way. This improves the nutritional value of pollen and avoids the need for freezing.

Natural and homemade beebread will keep for a considerable time and can easily be transported to the market and served - even in small quantities - as an excellent source of otherwise scarcely available nutrients. It can be sold clean and by itself or immersed in honey to make it more attractive in taste. Small pieces of comb can thus be sold or given away as candy.

The nutritional value of beebread is much higher in places where limited food variety or quantity create nutrient imbalances. It is particularly children who might benefit the most from regular pollen supplements in their diets.

3.5.3 In cosmeticsPollen has only recently been included in some cosmetic preparations with claims of rejuvenating and nourishing effects for the skin. The effectiveness has not been proven, but there is a considerable allergy risk for a large percentage of the population. Therefore this practice is not very advisable since it excludes a large proportion of potential customers and puts others at risk of having or developing very unpleasant allergic reactions.

Including alcoholic or aqueous pollen extracts (see 3.11.1) in cosmetic formulations appears to cause no or only rare allergic reactions. While little is known about the effectiveness of such extracts, they are still the preferred method of preparation for formulations in the cosmetic industry.

|

|

Hand and bee-collected pollen have been used for mechanical or hand pollination. The viability of hand-collected pollen can be maintained for a few weeks or months by frozen storage. Bee-collected pollen however, starts losing its viability after a few hours and increasingly with age. It is believed that some of the enzymes added by bees during foraging inhibit the pollen's ability to germinate on the flower stigma (Johansen, 1955, and Lukoschus and Keularts, 1968). Large-scale applications with mechanical dusters or by using dusted honeybees for dispersion were only moderately successful.

3.5.5 For pollution monitoringSince the 1980's, experiments have shown that pollen collected by honeybees reflects environmental pollution levels when examined for metals, heavy metals and radioactivity, (Free et al., 1983; Crane, 1984 and Bromenshenk et al., 1985). Contaminants can be quantified and sampling may be cheaper than most standard methods currently in use. Attempts have also been made to use pollen-collecting honeybees for the identification of potential mining areas (Lilley, 1983). The same effect of accumulating aerial deposits and selective plant secretions of minerals beneficial when used to monitor pollution control becomes a hazard if pollen from heavily polluted areas is used for human or animal consumption.

3.6 Pollen collection

Extreme care should be taken that pollen is not contaminated by bees collecting from flowers treated with pesticides. During, and for several days or weeks after treatment of fields or forests in an area of several square kilometres (in a circle of at least 3-4 2 km diametre) around the apiary, no pollen should be collected. This is independent of the method of pesticide application. Even systemic pesticides have been shown to concentrate in pollen of, for example coconut (Rai et al., 1977). Since a pollen pellet is collected from many flowers, even small quantities of pesticides per flower can be accumulated rapidly to reach significant concentrations.

Though pollen pellets are collected before they enter the hive, treatment of colonies for bee diseases, can contaminate the pollen pellets. Though, for example, cleaning of debris from the hive and bees regurgitating syrup, nectar or honey during collection of the pellets.

Pollen pellets are removed from the bees before they enter the hive. There are many designs of pollen traps (see Figures 3.7 to 3.8) some easier to clean and harvest, others more efficient or easier to install. The efficiency rarely exceeds 50%, i.e. less than 50% of the returning foragers loose their pollen pellets. Bees are ingenious in finding ways to avoid losing their pellets, like small holes or uneven screens and may even rob pollen from the collecting trays, if access is possible. Under some circumstances, pollen collection methods and regimes may interfere with normal colony growth or honey production. Therefore, standard beekeeping manuals should be consulted for the timing of collections (Dadant, 1992).

Pollen should be collected daily in humid climates but less frequently in drier climates. To avoid deterioration of the pollen and growth of bacteria, moulds and insect larvae, pollen should be dried quickly. Ants can remove considerable amounts from pollen traps. Krell (personal observations) reports that losses can be up to 30% in temperate climates.

Pollen needs to be dried to less than 10% moisture content (preferably 5 % or 8% according to some laws) as soon as possible after harvesting. A simple method uses a regular light bulb (wE and 1 1OV or 20W and 220V) suspended high enough above a pollen carton or tray so that the pollen does not heat to more than 40 or 45 0C. For solar drying, the pollen itself should be covered to avoid direct sunlight and overheating.

After drying, the pollen needs to be cleaned of all foreign matter. A tubular tumbler made out of a wire mash with a fan can clean considerable quantities of pollen pellets. Simpler winning methods can be used too. Benson (1984, in English) and Marcos (1991, in French) give very good accounts on trapping and subsequent processing of pollen.

Most types of pollen traps are currently only fitted to standard frame hives. are fitted to traditional log, clay or straw hives, small modifications are necessary.

Beebread is usually found on brood combs or combs near the brood nest. Available quantities are normally very small and inadvertently the brood comb and sometimes the whole colony are destroyed during harvest. A team of Russian scientists described a nondestructive means of extracting beebread from combs, harvesting 300-600 kg per year from 1500 colonies (Nakrashevich et al., 1988).

Some races of bees will store large quantities of beebread when colonies have become queenless, or the brood nest and/or plenty super space, are above an empty box with combs. Such manipulations will be more difficult or impossible with most traditional bee hives but modifications may be worthwhile. As mentioned earlier, beebread can also be made at home from bee-collected pollen(see section 3.12.2).

Other social bees usually store their pollen in special containers separate from the brood combs. These "pollen pots" can therefore be harvested without destroying the nest, but caution is necessary not to deplete the food sources completely.

3.7 Pollen buying

Quality control of pollen is difficult and under most circumstances impossible. It is therefore very important that the buyer knows the supplier well and can trust him. A reliable supplier should have all necessary storage and processing facilities and use them. Furthermore the production area, not only the residence or processing centre, should be free of agrochemicals and industrial pollution (and chemical treatments of the colonies). There are less and less of these regions in industrialized countries and a vast array and quantity of agrochemicals are now being used even in developing countries. More remote zones have problems with proper storage and transport and may require special collection and storage centres.

|

a) |

b) |

|

Figure 3.7: a) Pollen trap design to fit into a hive entrance between the bottom board and the brood chamber. b) The screen through which the bees have to pass can be made of a thick plastic sheet (at least 3 mm) with holes of 4.7 mm diameter for European honey bees and of 4.2 mm diameter for smaller bees such as from African races. Two wire screens with holes of similar size can also be used, spaced 4 to 7 mm apart. |

|

Sometimes, unethical, deceptive marketing or ignorance prevents

consumers or buyers to be informed about the above conditions. Until

reliable tests have been developed and legal requirements force more

frequent testing only responsible producers can be relied upon.

Buying processed products requires similar caution. The processor has to use gentle processing procedures to maintain those subtle qualities of pollen, which earned it its collected during four days. This type of trap is placed between bottom board and brood reputation. The buyer, whether consumer, retailer or processor has to be very careful and pay considerable attention to all handling and processing from the field collection to the final product. A truthful label could describe all the essential steps taken in order to guarantee the quality of the product. The need for highly ethical behaviour and knowledge at all levels is a requirement to be considered seriously, by anyone starting in this business, be it producer, processor or distributor. Forming a self-controlling organization, which certifies and controls producers and manufacturers may be useful or necessary to minimise fraud or avoid unreliable quality.

Figure 3.8: Pollen tray of a modified OAC trap (Waller, 1980) with two types of pollen chamber permitting better ventilation and pollen removal without disturbance of the colony. Returning foragers are forced to crawl through a double screen of 5-mesh wire (5 wires per inch) with 4-7 mm distance between screens. |

3.8 Storage

Pollen, like other protein rich foods, loses its nutritional value rapidly when stored incorrectly. Fresh pollen stored at room temperature loses its quality within a few days. Fresh pollen stored in a freezer loses much of its nutritive value after one year. Longer, improper storage leads to the loss of a few particular amino acids, which cause deficiencies in brood rearing (Dietz, 1975). When dried to less than 10% (preferably 5%) moisture content at less than 45°C and stored out of direct sunlight, pollen can be kept at room temperature for a several months. The same pollen may be refrigerated at 5°C for at least a year or frozen to –15°C for many years without quality loss as tested by feeding to honeybee colonies and recording brood rearing rate (Dietz and Stephenson 1975 and 1980).

Since sunlight, i.e. UV radiation, destroys the nutrient value of pollen, other more subtle characteristics probably suffer worse damage. Storage of dry pollen in dark glass containers, or in dark cool places, is therefore a requirement.

3.9 Quality

control

Only a few countries, such as Switzerland and Argentina, have legally recognized pollen as a food additive and established official quality standards and limits. Though sold in many health food stores, pollen is not considered an additive by the US FDA (Food and Drug Administration) and it does not have to comply with special standards. It is, however in the producer's own best interest to maintain the highest standards of cleanliness for his product.

The Argentinean standards require microbiological characteristics of not more than 1SOx1O0UFC/g aerobic microbes, 1O0UFC/g fungi and no pathologic microorganisms. The moisture content should not exceed 8% (controlled by vacuum drying at 45 mm Hg and 650C). Other limits include a pH of 4-6, protein content of 15-28% Kjeldahl (N x 6.25) of dry weight, total hydrocarbons of 45-55 % of dry weight and a maximum ash content of 4% of dry weight (determined at 600 0C).

Pollen used for cosmetic purposes should have the same, if not a better quality than that destined for consumption as food. The first quality control is assessment of gross contamination with foreign substances, i.e., parts of bee and hive debris. Further controls might include measurement of moisture content and a bacterial count. Determination of various agrochemicals, including drugs used inside bee colonies are possible and may be required in some circumstances. These analyses require sensitive, expensive chromatographic equipment.

Since air pollutants and agro-chemicals have been shown to accumulate in pollen collected by bees (see 3.5.5) pollen should originate from unpolluted areas with the lowest chance of contamination by agrochemicals, industrial pollutants and drugs applied by beekeepers. Producers from such areas should make particular note of this in their advertising.

Degradation of pollen nutrients by inadequate collection, drying and

storage can only be tested by bioassay, i.e. feeding pollen to honeybee

colonies and observing the quantity of brood reared, which is a very

lengthy and laborious process. Therefore, only reliable primary

products who have the required knowledge and facilities should be

considered as supplies.

3.10

Caution

The greatest risk of allergic reactions exists with the direct consumption of pollen. This, however, can be avoided by consuming pollen packed in capsules or coated pills which prevent direct contact with any mucous membranes. Once in the digestive tract, the body generally does not show any allergic reaction. Again, careful trials by sensitive individuals are recommended if consumption is assisted upon.

This preempts any foods in which pollen has been incorporated, but allows taking pollen for special health reasons. Barrionuevo (1983) and personal trials by the author, who is strongly allergic to some pollen species, confirmed that by avoiding contact with eyes, nose, mouth, throat and pharynx, no allergic reactions occurred with ingested pollen. Intestinal allergies to pollen are rarer than most food allergies (Schmidt and Buchmann, 1992). Still, careful trials by sensitive individuals are recommended for all products containing pollen.

Since there are so many different substances in the different pollen species to which people react with allergies, only some extractions or a general denaturalization can inactivate most of the allergens for commercial production. This probably ruins some of the beneficial characteristics of the pollen as well. Getting pollen from areas without the allergy-causing species may help individuals who want to consume pollen, but such identification and separation is unlikely to be feasible for commercial production.

A simple muscle resistance test (kinesiology) can show allergic sensitivities before actual contact with the substance occurs.

As a precaution, everybody, even those people who have not known any pollen allergies before, should first try very small quantities of the pollen or the product containing the pollen. Allergic reactions normally occur within a short period of time, from a few minutes to a few hours.

To avoid any problems with customers and with those who consume foods or use cosmetics and medicine-like products containing pollen, it would be advisable to include a warning on the product label, for example "This product contains pollen which may cause allergic reactions. Try small quantities first".

Pollen should not be collected or purchased from areas with heavy industrial, urban or agricultural pollution (pesticide). The geographical origin of the pollen should be known, and producers as well as buyers and retailers should be using adequate cold storage.

3.11 Market Outlook

Dried pollen prices in the USA range from US$5 to 13 per kg wholesale and US$11 30 per kg retail (American Bee Journal, 1993). Encapsulated pollen or pollen tablets sell vials of 50 to 100 units and retail at prices of up to US$900/kg, at least in Italy and the

The bulk pollen consumer market seems to be growing in industrialized countries, but pollen tablets are still a common feature of health food stores and command an excessively high price. Encapsulation and extraction of pollen lend themselves easily to small scale manufacturing and result in safer consumer products.

Most of the buyers and large scale sellers of pollen are also honey traders. Crane (1990) however reports that a lot of commercial pollen is not bee collected, but machine-collected from certain wind pollinated plants which release very large quantities of dry pollen.

At least in industrialized countries and those with increasing numbers of health conscious consumers, pollen consumption is likely to increase further. It is difficult to see how wholesale prices of bulk pollen could drop much lower. On the other hand, there seems to be a wide market for reasonably priced, encapsulated pollen and tablets.

Promotion of pollen from uncontaminated, unpolluted or even tropical forest areas may find a small consumer base in importing countries.

The high nutritional value of pollen should find special consideration in rural communities. Though not a traditional food, the ease of mixing it with other foods should facilitate acceptance. Rural hospitals could be the first to promote the use of pollen.

|

|

3.12 Recipes

Pollen can be added to a variety of foods and snacks. It does not involve any special adaptation of recipes, because the pollen is usually added in small quantities. However, pollen has a distinct flavour of its own and is usually slightly sweet. Thus it will alter delicate flavours and can even be detected in products with stronger flavours such as chocolate bars or granolas. Quantities should therefore be adjusted according to flavour.

Considering the sensitivity of pollen, its inclusion in products requiring processing (particularly heating) may cause a significant loss of beneficial effects. Fermentation into beebread may not only preserve many of the beneficial characteristics, but also add new enzymatic ingredients. Since pollen can easily be included in most recipes, only a few are provided here which might be marketable by small enterprises, including beekeepers. Various processed forms (encapsulated, pills, extracts) are presented (see Figure 3.9) and additional recipes can be found in Chapters 2, 5, 8 and 9.

3.12.1 Pollen extract

To avoid the granular structure of pollen or avoid some of the allergenic effects, pollen extracts can be prepared. The most common solvents for extraction are various types of alcohols. The higher the alcohol concentration, the more complete is the extraction of oils, fats, colours, resins and fat soluble vitamins from pollen. Solvents with lower concentration of alcohol mainly dissolve tannins, acids and carbohydrates. Therefore, with a variation of the alcohol concentration different types of extracts can be prepared. A propylene glycol extract contains most water soluble material, leaving behind the proteins, thus eliminating most if not all allergenic material. Such an extract is well suited for external applications such as in cosmetics. Oil extractions have been reported as inefficient. Treatment with diethylene glycol monomethyl ether discolours pollen and its extracts (D'Albert, 1956) where coloration may not be desired (cosmetics).

The following extract is prepared with a very high percent alcohol (95 % or more) to get most of the substances out of the pollen. The alcohol has to be food grade (fit for human consumption). Distilled beverages usually contain 40-60% alcohol or less, and so only produce less complete extracts.

A glass bottle or glazed clay pot is filled with 4 parts of 95% alcohol and 1 part of beebread (Dany, 1988). Bee-collected pollen can be used as well, but beebread has different (higher) nutritional values (see 3.12.2). Agitate the mixture at least once a day and leave it for 8 days. More frequent agitation improves extraction. The mixture is filtered through afine cotton cloth and stored in a dark glass bottle. It can be stored for a long time. The filtrate can again be washed in water and this weaker extract may be used immediately.

For further potentiation, 50 g of broken propolis can be added for extraction at the start. For medicinal purposes other herbal extracts can be added as well as mead, royal jelly etc.

A revitalizing concentrate, a teaspoon taken three times a day, is described (in parts by weight). Different proportions and additional ingredients are possible.

| 4 | Honey | 4 | Honey |

| 1 | Wheat germ (or wheat extract) | 0.5 | Pollen (or extract) |

| 1 | Pollen extract | 0.5 | Yeast (or stimulating plant extarct) |

| 1 | Dry yeast (brewers or bakers yeast) | 0.05-0.5 | Royal jelly |

| 0.1-0.4 | Royal jelly |

Normally, the term beebread refers to the pollen stored by the bees in their combs. The beebread has already been processed by the bees for storage with the addition of various enzymes and honey, which subsequently ferments. This type of lactic acid fermentation is similar to that in yoghurts (and other fermented milk products) and renders the end product more digestible and enriched with new nutrients. One advantage is almost unlimited storability of beebread in comparison with dried or frozen pollen in which nutritional values are rapidly lost. The natural process carried out by the bees can more or less be repeated artificially with dry or fresh bee-collected pollen. It is important however, to provide the correct conditions during the fermentation process.

The container

Wide-mouthed bottles or jars with airtight lids are absolutely essential. Airtight stainless steel or glazed clay pots can also be used. Containers should always be large enough to leave enough airspace (20 to 25 % of the total volume) above the culture.

The temperature

The temperature for the first two to three days should be between 28 and 320C; the bees maintain a temperature of approximately 34°C. After the first two or three days the temperature should be lowered to 20°C.

The high initial temperature is important to stop the growth of undesirable bacteria as quickly as possible. At this ideal temperature all bacteria grow fast so that an excess of gas and acid accumulates. Only lactic acid producing bacteria (lactobacilli) and some yeasts continue to grow. The former soon dominate the whole culture. This final growth of lactobacilli should proceed slowly, hence the reduction in temperature after 2-3 days.

The starter culture

It is best to start the culture with an inoculation of the right bacteria such as Lactobacillus xylosus or lactobacilli contained in whey. Freeze-dried bacteria are best if they can be purchased, but otherwise, the best cultures are those that can be obtained from dairies. Whey itself can be used. If the whey is derived from unprocessed fresh milk it should be boiled before use. A culture can also be started with natural beebread.

Preservation

Fermentation produces a pleasant degree of acidity (ideally pH 3.6-3.8). Some pollen species may promote excessive yeast growth but this does not spoil the beebread. If the flavour is strange or some other mildew-like or unpleasant odours arise from the beebread, discard it and try again. The final product, can be stored for years, once unsealed, it can be dried and thus is storable for many more months.

General conditions

For successful fermentation, exact quantities are less important than the correct conditions:

- the pollen to be fermented needs to be maintained under pressure

- the air space above the food needs to be sufficient (20-25 % of total

volume)

- the container needs to be airtight

>

- the temperature should not drop below 18°C

Ingredients (in parts by weight):

|

10

|

Pollen |

|

1.5

|

Honey |

|

2.5

|

Clean water |

|

0.02

|

Whey or very small quantity of dried lactic acid bacteria |

Clean and slightly dry the fresh pollen. If dried pollen is used, an

extra 0.5 parts of water is added and the final mix soaked for a couple

of hours before placing it in the fermentation vessels. If the mixture

is too dry, a little more honey-water solution can be added.

Heat the water, stir in the honey and boil for at least 5 minutes. Do not allow the mix to boil over. Let the mix cool. When the temperature is approximately 30-32 0C, stir in the whey or starter culture and add the pollen. Press into the fermentation container.

When preparing large quantities in large containers, the pollen mass should be weighted down with a couple of weights (clean stones) on a very clean board.

Close the container well and place in a warm place (30-32 0C).

After 2-3 days, remove to a cool area (preferably at 200C). 8 to 12 days later the fermentation will have passed its peak and the beebread should be ready. The lower the temperature, the slower is the progress of fermentation. Leave the jars sealed for storage.

3.12.3 Honev with pollen

Health food stores and beekeepers sometimes add up to 5 % (by weight) of pollen to honey. Using fresh pollen may lead to fermentation of the honey. Very well dried and finely ground pollen, however is more difficult to mix into the honey. Mix the pollen with a smaller quantity of honey and then add it to the final batch.

No matter how well the powdered pollen pellets are mixed into the honey, the pollen will separate and rise to the top of the honey in a very short time. This does not look very attractive but people will be more inclined to buy the product if the cause is explained properly on the label. This is a more palatable way to eat pollen than eating the dry pellets directly and appears to preserve the delicate characteristics of pollen very well. One way to avoid separation is to mix the pollen with creamed or crystallized honey (see recipes in Chapter 2).

The most likely customers for such products are people who are more knowledgeable and very health conscious. Therefore, other bee products such as royal jelly or propolis can be added to the honey mixture and a still better price may be obtained. How much this improves the health or nutritional value of the honey mix remains unanswered. Since honey improves the uptake of several nutrients, it may benefit the absorption of other substances as well. The resulting product should have a fairly long shelf life, but particularly if royal jelly is added, the product should be refrigerated.

3.12.4 Granola or breakfast cereals

Dry pollen pellets can be sprinkled directly over a prepared breakfast or incorporated in a cereal. Most prepared cereals require baking during processing or heating prior to eating, either would reduce the beneficial characteristics of pollen.

In order to be included in granola, pollen pellets need to be pulverized and then sprinkled over the cooling cereal (granola) while it is still moist and sticky. Inclusion in the granola dough prior to baking is not recommended.

Pulverized pollen pellets may be mixed dry with powdery breakfast cereals or sprayed onto the cereal together with a honey (sugar) syrup possibly including other flavours or fruit juice after roasting or baking of the cereal.

An alternative for baked granolas as well as dry cereals (muesli) would be to include one or more measured portions of dried pollen pellets in a separate bag, ready to be added by the consumer. This avoids problems for some allergic consumers, saves processing and preserves the beneficial characteristics of pollen.

Granola

A basic granola recipe requires:

One or more of the rolled or puffed grains (rye, wheat, barley, buckwheat, oat, rice or some of the local grains still grown in many parts of the world), heated vegetable oil and a variety of seeds, nuts, dried fruits, coconut, wheat germ, etc., shredded or finely chopped and added in proportions determined by the preference of the manufacturer or customer.

Dried milk powder can be added and dried fruits, fruit juice or honey can be used for sweetening. Any pollen or insect larvae should only be added after toasting.

The rolled grains are spread in a baking pan and toasted under fre quent stirring for 10 to 15 minutes in an oven heated to 1500C. Then the rest of the ingredients are added and toasted for another 15 minutes with more stirring. A simpler alternative which however reduces the nutrient value of some of the ingredients involves mixing all the ingredients together and toasting them - also at 150 0C - for 35 minutes. Once cooled, store tightly covered and preferably refrigerated.

A muesli or dry cereal usually consists only of dried ingredients. No toasting or baking is necessary. The same granola ingredients can be mixed but without the oil. For consumption, the muesli is mixed with cold milk, water or fruit juice. Alternatively, it may be briefly boiled to soften the rolled grains.

Granola bars

To make granola bars, the same granola mixture should be pressed into the preferred shape after the first toasting. The second toasting is then completed at a slightly lower temperature and over a longer period of time. If sufficient honey is used, the hot mixture can be pressed into oiled forms also just before the toasting is finished, when the granola is still moist and sticky.

The sample recipe below is adapted from "The Joy of Cooking" (Rombauer and Rombauer Becker, 1975):

Ingredients (in parts by volume, e.g. cups):

|

2

|

Rolled oats |

1

|

Dry milk |

|

2

|

Rolled rye or barley |

2

|

Coarsely chopped almonds |

|

2

|

Wheat or corn flakes (or rolled) |

2

|

Shredded or flaked coconuts |

|

1

|

Vegetable oil |

2

|

Hulled sunflower seeds |

|

1

|

Honey |

1

|

Sesame seeds |

|

3

|

Wheat germ |

q.s.

|

Pollen, insect larvae or dried fruits |

Preheat the oven to 150 0C. Scatter the rolled grains on a baking sheet or pan and toast for 15 minutes in the oven, stirring frequently. Slowly heat the oil and honey and add the remaining ingredients. Then combine with the toasted grains and spread thinly in the pan, continuing to toast in the oven and stirring frequently for another 15 minutes or until the ingredients are toasted. While the ingredients are still warm and sticky, sprinkle the pollen pellets, pollen powder, insect larvae or chopped dried fruits onto the granola and form into bars of the desired size.

There are many ways of preparing candy bars with nuts, chocolate, grains, popcorn and puffed rice to which pollen or even larvae can be added For replacing part of the sugars with honey in any recipe see the recipe section in Chapter 2.

The following is a general recipe from the same source as the granola and can be modified substantially for different flavours, textures etc.

Ingredients (in parts by volume):

| 3 | Honey |

| 4 | Butter |

| 0.3 | Water |

| 4 to 6 | Slivered almonds (or other nuts, larvae or pollen) |

| 3 | Melted semisweet chocolate |

| 1 | Finely chopped nuts, larvae, pollen or raisins |

Sliver or break large nuts such as almonds, hazelnuts and brazil nuts

but, peanuts, for example, can be left whole. If a roasted nut flavour

is preferred, add the nuts at the beginning to the honey, butter and

water mix. If not, spread them on a buttered slab or pan and pour the

cooked syrup over them.

Heat the honey, butter and water in a heavy skillet. Cook rapidly and stir constantly for about 10 minutes or until the mixture reaches the hard-crack stage (1500C). Add the nuts and larvae quickly and pour into a buttered pan or slab or pour the syrup over the nuts on a buttered slab. When almost cool, sprinkle with pollen powder (or crushed pollen pellets) and brush with the melted chocolate. Before the chocolate hardens, dust with the finely chopped nuts, larvae or pollen. After cooling, break into pieces and wrap individually.

In order to form even-sized bars or round shapes, pour the syrup into buttered moulds. Before completely cooled, these bars can be dipped in melted chocolate and sprinkled with any of the above materials for decoration. For special care with chocolate coatings, see also recipes in Chapter 2.

Many regions have their own special and preferred sweets and candy bars. Pollen can be incorporated into many of these recipes. Such incorporations should take place towards the end of processing, and the first cooling phase, in order to preserve as much as possible of the subtle characteristics and benefits of the pollen.

Cereal-fruit bar

The following two recipes (adapted from Dany, 1988) preserve all the nutritious values which might otherwise be destroyed through heating in the previous preparations. The baking described in the granola and candy bar recipes is replaced by drying at temperatures of 40 to 45 0C. This also facilitates processing for those who do not have access to baking stoves.

The oats used here can be replaced by one or a mixture of other grains. They should however be rolled into flakes. The pollen extract (3.12.1) mentioned here, can also be powdered, bee-collected pollen or the fermented manmade beebread mentioned in section 3.12.2.

Basic Ingredients (in parts by volume):

|

4

|

Rolled oats |

|

1

|

Boiled water or fruit juice |

|

0.2

|

Vegetable oil or fat |

|

0.2

|

Dry yeast (brewers yeast, bakers yeast or other) |

|

0.6-1.2

|

Pollen extract |

|

q.s.

|

Salt |

The following ingredients (by piece per 50 g. of oats) can be mixed

according to taste and availability:

|

2

|

Figs | Or | 1 tablesp | Chopped chocolate |

|

½

|

Banana | 4 | Dried apricots | |

|

½

|

Apple | ½ | Apple | |

|

2 teasp

|

Ground almonds | 1 tablesp | Soybeans (toasted or boiled) | |

|

1 tablesp

|

Sunflower seeds | 1 | ||

|

1 tablesp

|

Raisins | 1 tablesp | Raisins | |

|

5

|

Dates | 1 tablesp | Chopped nuts |

A small amount of honey can be added for sweetening.

For a more unusual flavour the following is recommended:

|

50 g

|

Rolled oats |

|

30 g

|

Fresh pureed tomatoes |

|

1-2 tblsp

|

Pollen extract |

|

½

|

A pureed green pepper |

|

½

|

Finely chopped onion |

|

1

|

Clove of garlic |

|

s.q.

|

Small quantities of herbal spices: estragon, thyme, rosemary, marjoram, oregano or chili pepper (according to taste) |

The pollen extract is dissolved in the water or fruit juice and the

liquid poured over the rolled grains. Stir and leave for a while to

allow absorption of the liquid, then add the other ingredients, mix and

knead well and if necessary add a little water.

Spread the dough to dry on an oiled slab, board or sheet, to a thickness of 1 cm or less. Wax paper or a food grade plastic foil may also be used instead of the oiled slab. The thinner the dough is spread, the better the drying. Precut the dough into bars with a knife

Drying:

Slow drying at low temperatures is recommended. In a warm room, in an opened solar drier or in the direct sun, the mixture should be covered with a cloth to exclude flies, bees, dust and other contaminations. In an oven, the temperature should not exceed 50 0C with a door left partly open.

The fruit and nut mixtures will keep for a couple of weeks but the vegetable mixture should be consumed as soon as possible. Individual bars can be wrapped in waxed paper or plastic foil approved for food use.

3.12.6 Pollen supplements and substitutes in beekeeping

Haydak (1967) successfully tested a soybean flour, dried brewer's yeast and dry skimmed milk mixture in the proportions of 3:1:1. As a pollen substitute fed to honeybee colonies during a period of shortage, the mixture stimulated early colony development and overcame pesticide damage. One kilogramme of this substitute should be mixed with 2 litres of a concentrated sugar syrup in order to make it attractive to the bees. The sugar syrup is mixed in proportions of 2 parts granulated sugar with 1 part of hot water. A few egg yolks can be added as well and the mixture should be left standing overnight. The final consistency should be such that the paste stays on top of the frames, preferably wrapped in wax paper to prevent it from drying out.

Pollen supplements can be mixed from dried bee-collected pollen and various types of sugar syrup. However, the nutritional value of pollen (as larval food) deteriorates with time and under certain storage conditions as described in section 3.8. A more detailed discussion on this subject can be found in Dietz (1975).

3.12.7 CosmeticsThe claims attributed to the cosmetic effects of pollen have not been proven nor do pollen-based products seem to outperform alternative non-allergenic products. Given the risk to a growing percentage of allergic customers, it is not possible to recommend use of pollen in commercial products. If one wants to include pollen in personal cosmetics, the pollen pellets should be well dried and carefully ground to a very fine powder. They are likely to remain slightly abrasive, but can be ground further. The powder is mixed without heating at 1 % or less into any preferred preparation. Some alcoholic extracts, appear to cause no allergic reactions. Unfortunately, nothing is known about their effectiveness. For recipes see Chapter 9.

3.12.8 Pills and capsulesThe best profit margin for selling pollen appears to be in selling it pill form. As mentioned earlier, the value of 1 kg of pollen pills or capsules can reach US$900 as compared to US$1 11-30 for 1 kg of dried pollen in the same stores. This enormous price margin cannot be achieved everywhere, but reflects a consumer attitude that exists in some countries.

In order to process pollen into pills a simple machine is necessary, which even second hand may cost a few thousand dollars. A paste of pollen and honey is prepared for pressing. No additives are necessary but gum arabic or a little pulverized wax can be incorporated. Coating the pills with wax render them non-allergenic, i.e. preventing contact with mucous membranes. If no pill press is available, more gum arabic or other gel and wax mixtures should then be used so that pills can be formed individually (see also 5.16.5).

For small enterprises, a more economical and feasible way of marketing dried pollen pellets for human consumption is by encapsulation. Gelatine capsules of 0 or 00 size are filled with the dried pollen. If the filling is conducted carefully, little or no pollen should be left on the outside, where it could cause harm. Extra cleaning may be required and a warning about possible allergic reactions should be printed on the label.

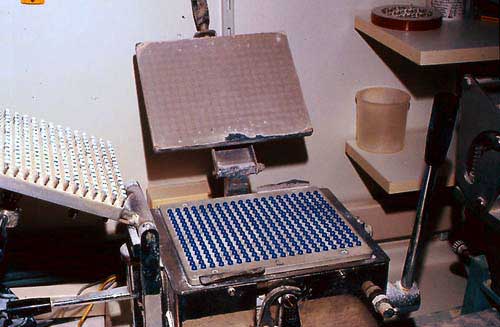

There are small, manually operated capsule fillers available for just a few dollars. Medium-size machines, which can fill 500 to 1000 capsules per hour can be made by a precision workshop (see Figure 3.10 and Annex 2). Bigger machines handling up to 10,000 capsules per hour are available for large scale production. Pollen can be encapsulated dry in its original pellet form, as a ground powder, a honey/pollen paste, or in combination with other products particularly honey (for longer preservation) but also with propolis and royal jelly. Capsules should be stored in well sealed glass or plastic bottles. They should preferably be refrigerated and consumed within 180 days. Frozen storage and the use of higher proportions of honey or propolis will significantly prolong the useful storage life.

|

a)

|

b) |

|

Figure

3.10: Medium-size hand-operated capsule filler. a) One machine

separates the capsule halves, sorts and places them into separate

trays. b) A second machine allows filling of capsule halves in

presorted trays from a) and then closes the capsules. Using both

machines, 1500-4 000 capsules can be filled, compacted and closed per

hour by one person.

|

|

|