|

|

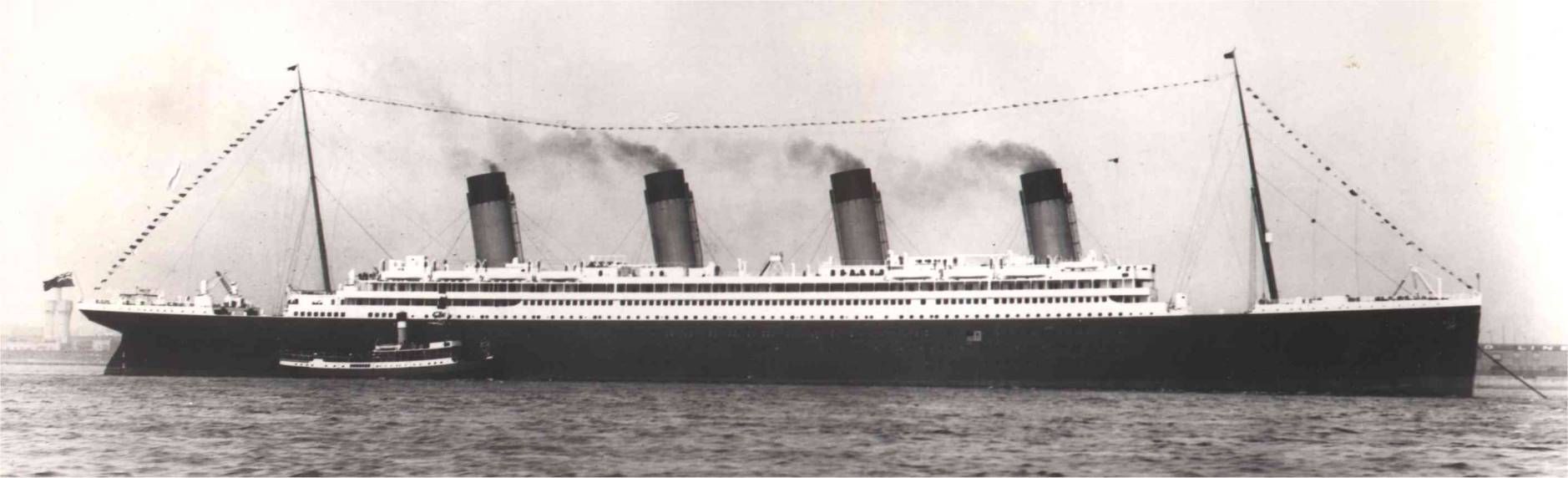

| On a warm summer evening in 1907, Joseph Bruce Ismay met with Lord James Pirrie, director of the shipbuilding firm Harland & Wolff of Belfast, Northern Ireland at his London house for dinner. While Ismay�s and Pirrie�s wives retreated into another room, the two of men discussed Cunard�s new liner Lusitania. Something had to be done to keep White Star in the race for the Atlantic trade after the new liner and her sister Mauretania inevitable amazed crowds with their size, speed, safety and elegance. The two men, lingering over cigars, concocted a plan to build 2 new liners with a third to follow, 50% larger than Lusitania and Mauretania, much more elegant, though not as fast, and the promise of a third sister if the first two proved successful enough. Their names would be the final touch to their supremacy, all coming from Greek mythology, the Olympians, Titans and Giants. Lord Pirrie's nephew, Thomas Andrews was assigned chief designer of the ships after Harland & Wolff�s former chief Alexander Carlisle retired in 1909 while Olympic was being built. Her keel plate was laid on December 16th, 1908, housed in the �Great Gantry� as it became known; two huge gantries built over three existing ones, for the first two ships were to be built side by side, a first in the shipbuilding world for ships of such a size. Thomas Andrews mused of the Olympic-Class ships �it takes three million rivets and a lot of sweat to build a fine ship.� These are the words the Harland & Wolff shipbuilders worked by. Three million rivets were pounded into Olympic�s armour plating and gradually the ship took shape, mirrored by the almost identical Titanic next to her. Thomas Andrews must have been proud of the ships he was bringing to life, their almost yacht like appearance sure to cut an impressive figure with their graceful sloping amidships and raked funnels dominated the horizon as they ploughed their way across the Atlantic. Finally, on October 20th 1910, Olympic was launched to a massive crowd. Painted light grey for photographers, the 24,600 ton hull slid gently into the River Lagan before being towed to the fitting out berth, specially constructed for the ship�s enormous 882.5 foot length. The heavy machinery was added first. Four reciprocating engines, 4 stories tall powered her two wing propellers, while a centre turbine run off excess steam powered a smaller, forward only propeller. Twenty-nine boilers were added into the hull to provide the steam power to get the ship across the Atlantic in seven days. Her four funnels were among the largest made; if placed on a railway line, two trains could easily pass inside them. The fourth funnel was really a dummy though, used to ventilate the reciprocating engine room and kitchens as well as having a space for storage at the boat deck and a ladder to climb up from inside. The original plans called for three, but a fourth was added to give the illusion of size and to compare with the four fitted to Lusitania and Mauretania. Unlike the Cunarders, whose funnels were spaced together and forward of the superstructure, the Olympic Class' would have their spaced evenly along the boat deck. Finally, Olympic was moved from the fitting out berth to the graving dock where her final fittings would be added. Now with the ship's building almost complete, the people of Belfast were looking increasingly forward to her first voyage. On May 31st, 1911, Titanic was launched to a massive crowd at Belfast. Olympic had been put through her sea trials with two specially built tenders, Nomadic and Traffic which would be used to serve her and her sisters in Cherbourg, France, and as the Titanic floated empty in the Lagan, Olympic was steamed proudly toward her sister where Lord Pirrie handed the ship over to a very proud Bruce Ismay and the White Star Line before she sailed with dignitaries back to Liverpool, and then on to Southampton for her maiden voyage. Olympic sailed on her maiden voyage from Southampton on June 14, 1911 bound for New York. Passengers were amazed at her size as she lay in Southampton�s White Star Dock, especially built for the new liners. Travelling on her maiden voyage was Joseph Bruce Ismay and Thomas Andews, both mingling with the passengers and deciding whether there were any problems could be solved before the ship returned to England, and what they could incorporate into Titanic before she sailed. On the bridge of this new vessel was Captain Edward John Smith, commodore of the White Star Line. Olympic�s luxury was without a doubt the best of it's kind at sea. Second and even third class were treated equal to first class on other lines. Accordingly, first class were treated like royalty. Entering the dining room on D-Deck from the Grand Staircase, sweeping down under a wrought iron and glass dome from the boat deck, the passengers couldn�t dream of making a more splendid impression on their travelling companions. Olympic was given a huge welcome in New York, one than neither of her sisters would see. So proud of her was Ismay that he sent a telegram back to Lord Pirrie exclaiming "Olympic is a marvel, and had given unbounded satisfaction". The maiden voyage was marred by one mishap, however. While docking in New York, the tug O.L. Hallenbeck was drawn under Olympic�s stern by a blast from the liner�s propellers. Hallenbeck was badly damaged, enough for the owners to sue White Star, who counter-sued. In the end, the courts dropped the case due to lack of evidence. On September 20th, 1911, once again under the command of Captain Smith (but with Southampton pilot George Bowyer at the wheel), Olympic had begin her fifth crossing and was sailing down Southampton�s Solent shortly after noon. As she was passing the Isle of Wight, she saw a smaller British cruiser, HMS Hawke. Hawke was ahead of Olympic on a parallel course, but as the liner, six times the size of the Hawke, overtook the cruiser, passengers and crew on Olympic saw the warship�s beam turn to face Olympic. Drawn uncontrollably towards the liner�s aft quarters, the reinforced how of the Hawke bow punctured Olympic above and below the waterline. The cruiser had a large cement ram under the waterline which broke off after tearing into two of Olympic�s 16 watertight compartments. As Olympic sped onwards, the Hawke nearly capsized because of her lack of balance with the missing ram and large hole in her bow, spinning like a top as she finally tore free. Although the damage to both ships was very great, thankfully no one was injured on either ship. Hawke's bow was crumpled, but she was able to limp back to port under her own power. Olympic was able to do the same after her passengers were unloaded by tender, even though two of her watertight compartments were flooded, and after some brief repairs, she sailed slowly back to Belfast for repairs. An inquiry was held into the ramming, and the outcome showed the Hawke as the perpetrator, but also the innocent victim. The Olympic�s great bulk had sucked the cruiser into the side of the liner, the accident proving the dangers associated with ships of Olympic�s size. At 45,000 tons, she was simply too large to travel near smaller ships, especially one as small as the Hawke, weighing in at a meagre 7,000 tons. A call was put out for the channel widened for Olympic and her soon to be completed sister Titanic, but would go unheeded until a similar occurrence (but no accident) happened when Titanic left Southampton on her maiden voyage. Once again under the command of Captain Smith, in March 1912, Olympic struck an underwater obstruction and lost a propeller. A spare one was taken from Titanic, now only a month before her maiden voyage. At Belfast where the repairs took place, the two liners sat together. It would be the last time the two ships were seen together. Because Olympic was priority at Harland & Wolff, Titanic�s maiden voyage date, which thankfully had not been made public, of March 20th was put back to April 10th. Leaving Harland & Wolff in the late evening of April 2nd after her sea trials, Titanic and Olympic communicated via wireless and the papers stated the two ships had passed each other �somewhere off Portland�. On April 10th 1912, Titanic left Southampton on her maiden voyage. It would be one she would never complete. She struck an iceberg late April 14 and sank early the next morning, taking 1,523 terrified people with her, including Captain Edward Smith and Thomas Andrews. The massive loss of life was due to the lack of lifeboats, only space for 1,178 of the 2,228 aboard. Sailing outbound from New York and 500 miles away, Olympic heard Titanic�s desperate wireless for help. Captain Herbert Haddock quickly turned the ship towards her sinking sister and had every available hand pour on every ounce of steam they could muster. Olympic sailed at 24 knots for some time before hearing Titanic had gone down with a great loss of life, and the survivors were taken aboard Cunard�s Carpathia. Olympic asked whether they should take the passengers from the little Cunarder, but Bruce Ismay, safely aboard Carpathia but locked in the chief surgeon�s cabin waved her away, not wanting the passengers to see a double of the ship that just sank with their husbands. Olympic was taken out of service right after the accident to be fitted with more lifeboats. 24 collapsible boats were added, but not long before her next voyage, many of the stokers deserted the ship refusing to sail citing the high death toll of stokers on Titanic. The voyage was called off two days after the arranged sailing date and stokers were called in from other ships to fire her until her major overhaul. Her routine overhaul included the installation of more wooden boats, but she also had her bulkheads raised and double bottom raised up the sides of the ship. The renovation took over six months and thousands of dollars. Finally, she was returned to service after six months, but now she had the German Imperator to contend with, not to mention the ships that had brought about her very existence, Lusitania and Mauretania. In February 1914, her last sister Britannic (formerly Gigantic, but her name changed after the Titanic disaster) was launched. She however would never see a paying customer because when war broke out in August 1914, the admiralty required large ships to be turned into floating hospitals to take the wounded and sick from the front lines back to England. There was no better ship for the job than the Britannic, but it was in this guise was sunk in November 1916 off Greece after striking a mine. Interestingly enough, despite all the safety features incorporated into her, even more so than Olympic, she still went down in 55 minutes. Thankfully, the loss of life was low, only 30 fatalities out of 1066 aboard. Olympic remained in passenger service for the first few months of the war, and it was during this hazardous period she rescued the crew from a British battleship, HMS Audacious that had hit a mine and was sinking. Because of the quick thinking of Olympic�s crew, not one life was lost. In September 1915, 4 months after the loss of the Lusitania, the Admiralty requisitioned Olympic as a troop ship. Painted in 'dazzle' colours and fitted with many more lifeboats along her decks and with guns mounted on her aft docking bridge and forecastle, Olympic looked very intimidating. She joined Mauretania, her nearly brand new running mate Aquitania and many other ships ferrying troops between battlefields. She had four close encounters with German U-boat submarines during the course of the war, and in one instance rammed and sank the U-103 which was trying to attack the liner. Although it was only a glancing blow, with over 46,000 tonnes behind her (raised because of post-Titanic safety measures) it was enough to send the sub to the bottom with nearly all hands. Olympic slightly damaged her prow, but it was repaired shortly afterward. This is the only reported case of a troop ship sinking an enemy war ship of any kind throughout the course of the war. Those aboard collected a purse and with the funds bought a plaque that hung in her first class smoking room to remind passengers of the ship�s war service. It is rumoured also that on the same day, she destroyed another U-boat with her aft guns, though this has never been established. All up, Olympic transported 120,000 civilians and military personnel across the seas and like all liners in this duty, helped bring the war to a close quicker. Being able to move 10,000 people across the Atlantic dramatically reduced the length of the war. Because of her service in the first world war, Olympic was given the nickname 'Old Reliable', proving time and again that she was unsinkable. After a post war refit, Olympic was back in her civilian colours by July 1920, but with the loss of her two other sisters, she was in desperate need of a running mate. This is where HAPAG stood in. The Hamburg-Amerika line (HAPAG) had decided many years earlier to build three massive liners to rival Cunard's greyhounds and the Olympic class. Like these two lines, HAPAG too would feel the blow of the war, but would be the most worse off. The second ship in the fleet, Vaterland, was impounded in Boston harbour at the start of the war, and after America entered the war, she was requisitioned as a troop ship and re-named Leviathan. After the war, she was given to the United States Line. Imperator, the first ship in the fleet was given to the Cunard line, and after serving for just over a year in her old name and colours, she was renamed Berengaria. White Star Line would receive the largest of the three, and in turn, the largest liner in the world, Bismarck. Unfinished, she was sabotaged once by the Germans, not wanting to part with the liner, but damage was minimal and quickly repaired, and finally, she joined the Olympic under her new name, Majestic. Although the line had a two ship service now, the new owners of the WSL wanted a third to compete with Cunard's Mauretania, Aquitania and Berengaria. So desperate they were that they put the former North German Lloyd's Columbus, now Homeric, in service with these massive ships. Homeric was tiny compared to Olympic, and much slower too, but it was all they had. Finally, White Star could boast about their three ship service. By the late 1920s, Olympic was starting to show her age. Though still a beautiful liner, many more newer ships were surpassing her in terms of speed, size and luxury. Her 1911 design seemed to hearken back to an earlier era, and despite costly renovations to make her look more modern on the interior, she still fell victim to the newer ships. Regardless of this, she still sailed with Majestic and Homeric, operating between Southampton and Montreal during the winter months. By 1930, with the economic recession in full thrust, Olympic was losing profit, as was many of her other companions. Cunard�s new unnamed liner, known to the world as �Hull 534� sat on the stocks, unfinished. Cunard approached the government for a loan to finish the liner, which the government agreed upon, on the condition Cunard and White Star merged. Only 6 days after the merger, flying the Cunard-White Star flag for the first time, Olympic faced her final dark moment. Steaming through a think bank of Atlantic fog, she rammed the Nantucket Lightship, leaving 7 of the Lightship�s 11 crew dead. Olympic's bow was seriously damaged in the accident, and was patched up quickly, though her new owners knew that the great ship had finally outlived her usefulness. In March, 1935, she made her last crossing to New York. When she returned to England, she was decommissioned and laid up in the murky backwaters of Southampton Harbour at Berth 108, known as �Death Row�. She had company though, Mauretania was also decommissioned and lying at anchor there. Mauretania left first, followed shortly afterward by Olympic. Sailing under reduced speed, she travelled up the Tyne River to the Scottish town of Jarrow where she would be scrapped. To break her up would take two years and thousands of man hours, about the same as what it was to build her. Finally, her stripped hull was dragged by tugs to Inverkeithing where her final demolition was to take place. Many of her fittings were sold off to collectors and have been scattered to the many corners of the globe. Quite a few pieces of woodwork from the first class lounge ended up in the White Swan Hotel in Alnwick, England, and the clock representing Honour and Glory Crowning Time from the ship�s Boat Deck landing of the Grand Staircase is on display in Southampton. A ship which survives the ocean will suffer a much more indignant death than one that had been claimed by it. May Olympic's spirit sail forever. |

|