2) Nevada City, California

3) Korea

4) Anarchy

5) Candicy

6) Bum on the rod

7) Enormosly wealthy

8) Mess with people

9) Natural resources

10) Heros

11) half a ghost town

12) holding on

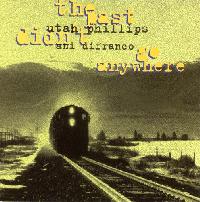

Released in 1996

RBR009

bridges

that's what i do is collect stories and songs and poems. i seek out the elder's and garner

stories and songs and poems. characterized critically as "oh, that's that 60's stuff". like

somebody doing old rock and roll would be doing "that 50's stuff". well, or, this is the 90's,

you know. i have a good friend in the east. a good singer and a good folksinger. good song

collector who comes and listens to my shows and says "you sing a lot about the past, you

always sing about the past. you can't live in the past, you know. and, um, i say to him i can go

outside and pick up a rock that's older than the oldest song you know and drop it on your

foot. now the past didn't go anywhere, did it? it's right here, it's right now. i always thought

that anybody who told me i couldn't live in the past was trying to get me to forget something

that if i remembered it would get them in serious trouble. no it's not that 50's, 60's, 70's, 90's,

that whole idea of decade packages, things don't happen that way. uh, the vietnam war heated

up in 1965 and ended in 1975. well, what's that got to do with decades? um, that packaging

of time is a journalistic convenience that they use to trivialize and to dismiss important events

and important ideas. i defy that. time is an enormous long river and i'm standing in it, just as

you're standing in it. my elders were the tributaries and everything they thought and every

struggle they went through and everything they gave their lives to and every song they created

and every poem they laid down flows down to me. and if i take the time to ask and if i take

the time seek, if i take the time to reach out i can build that bridge between my world and

theirs, i can reach out down into that river and take out what i need to get through this world.

bridges from my time to your time, as my elders from their time to my time. and we all put into

the river and we let it go and it flows away from us and away from us until it no longer has our

name, our identity. it has its own utility and it's own use and people would take what they need

and make it part of their lives. sometimes while at length, the past didn't go anywhere, did it?

nevada city, california

at the onset, those of you who may have heard me should probably turn to those who may

have not, and calmly reassure them that this is in fact what happens when i sit on a stage. not

much more. this is about it. you'll notice no sudden or dramatic change in either my either my

instrumental or vocal attack as it were. this is nonetheless an american folk song. did you

recognize it as such? of course you would, you don't hear them much anymore, don't hear

them on your am radio, huh? folksingers hardly ever sing them, that's because they're boring.

folk music is boring. wack fall the di-do, blow ye winds, hi-ho, that's boring. but i am a

folksinger, this is a folk music organization, you are ostensibly the folk, and that's bah. that

means we own this song together, right? we have thereby incurred certain social obligations

which we will faithfully discharge, right? we're going to sing this song together, boring or not. i

was still in nevada city, california, up there in the foothills of the sierra. i call them the

"footh-ills" because it's spelled like that. oh, the old gold mining town, i've talked to some of

you about that. twenty-seven hundred people there, one of the forty-niners towns. and i also

told you about the only social life in town being the books of harmony new age bookstore,

where people go down in the evening and channel dolphins and martians. it's a new age

chrono-synclastic infindibulum, or epicenter as it were, nevada city, california. well, i was gone

for a bit on one of the trips since i saw you last and i got back and my wife had bought the

bookstore. so i am now ostensibly part proprietor of a new age bookstore in nevada city,

california, can you picture that? and i'm open to all those things. if you live in california, you've

got to be open. if you're not, they pry you open. and i read as much as i can because i've got

all the new man's literature in there. most of my men friends belong to men's drumming circles.

do they do that here? it's healthy. they're out there in the wilderness caterwauling and flailing

away at those things and dragging their scrotums through the underbrush. it's healthy i

suppose. we swing in the trees and we steal sheep. we don't have a drumming leader, we

have a grooming order. robert bly came by on one of his workshop trips to teach us how to

drum. we ate him. nevada city, california. anyone know where i'm talking about? good. gonna

get narps. you got narps around here? new age rural professionals. out cruising the backroads

in their old carryalls with their car stereos blaring meditation music out into the wilderness. it's

a caution. tall place lighting struck by the parapathetic ruminations of the tibetan ruling class in

exile. a lot of buddhists around there. meanwhile, this very minute old jesse mcveigh, the well

digger, nobody knows how old he is, lived in that county all of his life, is sitting at the bar of

the national hotel this very minute looking at the freaks out in the street and muttering under his

breath, "no matter how new age you get, old age going to kick your ass."

korea

since the kids have been little, they've always known that i've vanished from their lives

periodically. and they've never really had any idea what it is that i do. what do i do? if i don't

know, why should they? we never traveled together at all, you know. brandon, the

fourteen-year-old, he got to travel with me during the summer. but we got a chance to talk to

each other as adults. you know, well, as adults, instead of just father and son. we left boston,

we were headed up to the left bay cafe in blue hill, maine, and brandon, just about

marblehead, turned to me and he said, "how did you get to be like that?" it's a fair question. i

knew what he meant, but he didn't have all the language to say exactly what he meant. what he

meant to say was, "why is it that you are fundamentally alienated from the institutional structure

of society?" and i said, "well, i've never been asked that, you know? now don't listen to the

radio and don't talk to me for half an hour while i think about it. so we drove and talked. we

were on highway 1 because it was pretty and close to the water. got up toward the maine

border, and there was a picnic area, off to the side some picnic tables. it was a bright, clear

day. so i pulled into their parking lot, we sat down at the picnic tables and i said, "now, sit

down, i want to tell you a story, cause i've thought about it." i said, "you know, i was over in

korea. and he said, "yeah, i've always wondered about that, did you shoot anybody?" and i

said, as honestly as i could, "i don't know. but that's not the story," i said, "listen to what i'm

telling you. i was up at the khumer rhea gap by the imjin river. there were about 75,000

chinese soldiers on the other side and they all wanted me out of there with every righteous

reason that you could think of. i had long since figured out that i was the wrong person in the

wrong place at the wrong time for the most specious of reasons. but there i was, my clothing

was rotting on my body. every exotic mold in the world was attacking my clothing and my

person. my boots had big holes in them from the rot. i wanted to swim in the imjin river and

get that feeling of death, that feeling of rot off of me. the chinese soldiers were on the other

side, they were swimming, they were having a wonderful time. but there was a rule, a

regulation against swimming in the imjin river. i thought that was foolish, but then a young

korean, a carpenter for us by the name of yin sukon, all of his family had been killed off in the

war. well, he said to me in what english he had, "you know when we get married here, the

young married couple moves in with the elders. they move in with the grandparents. but there's

nothing growing, everything's been destroyed, there's no food. so the first baby that's born, the

oldest, the old man goes out with a jug of water and a blanket and sits out on the bank of the

imjin river and waits to die. he sits there until he dies and then will roll down the bank and into

the river and his body will be carried out to the sea. and we don't want you to swim out in the

imjin river because of our elders are floating out to sea. that's when it began to crumble for

me, you know. that's when i, well i ran away. not just from that, i ran away from the blueprint

for self-destruction i had been handed as a man, for violence in excess, for sexual excess, for

racial excess. we had a commanding officer who said of the gi babies, fathered by gis and

korean mothers, that the korean government wouldn't care for, so they were in these

orphanages, and he said "well, as sad as that is, someday this will really help the korean

people because it will raise the intelligence level." that's what we were dealing with, you know.

well, i ran away. i ran down to seoul city, down toward ascomb, not to the army. i ran away

to a place called the korea house. it was korean civilians reaching out to gis to give them some

better vision of who they were than what we were getting up of the divisions. and they hid me

for three weeks. late one night, because they didn't have any clothes that would fit me. late

one night, it was a stormy, stormy night, rain falling in sheets, i could go out because i figured

that nobody would see me, we walked through the mud and rain. seoul city was devastated,

and they took me to a concert at the awol women's university. a large auditorium with shell

holes in the ceiling and the rain pouring through the holes and clyde lights on the stage hooked

up to car batteries. this wasn't the uso, this was the korean students association. the person

that they had invited to sing, i was the only white person there, the person that they had invited

to sing was marian anderson, the great black operatic soprano who had been on tour in japan,

you see. there she was singing "oh, freedom" and "nobody knows the trouble i've seen." and i

watched her through the rain coming through the ceiling and thought back to salt lake, to my

father, sid, who ran the capital theatre. it was a movie house, but it had been an old vaudeville

house and he wanted to bring live performances back to the capital. in 1948, he had invited

marian anderson to come and sing there. and i remembered we went to the train station to

pick her up and take her to the biggest hotel in town, the hotel utah. they wouldn't let her stay

there because she was black. and i remember my father's humiliation, and her humiliation, as i

saw her singing there through the rain. and i realized there, right then, brandon, right then i

knew that it was all wrong. that it all had to change and that change had to start with me."

anarchy

i learned in korea that i would never again, in my life, abdicate to somebody else my right and

my ability to decide who the enemy is. got back from korea, i was so mad at what i'd seen

and done, i wasn't sure i could live in the country again. i got on the freight trains up in everett,

north of seattle, and kind of cruised the country for two years, making up songs, but i was

drunk most of the time, and forgot most of those. i had heard that there was a house in salt

lake city by the roper yards of the denver grand and western where there was a clothing

barrel and free food, so i got off the train there. i was headed for salt lake anyway. i found that

house, right where they said it was, but most of all i found this wiry old man, sixty-nine years

old, tougher than nails, heart of gold, a fellow by the name of ammon hennacy. anybody know

that name, ammon hennacy? one of dorothy day's people, the catholic workers, during the

30's they started houses of hospitality all over the country, there are about eighty of them now.

ammon hennacy was one of those, he'd come west to start this house i'd found called the joe

hill house of hospitality. ammon hennacy was a catholic anarchist, pacifist, draft dodger of two

world wars, tax refuser, vegetarian, one man revolution in america, i think that about covers it.

it was pure hell. the first thing he did was he said, after he got to know me, he said "you know

you love the country. you love it. you come in and out of town on these trains and singing

songs about different places and beautiful people. you know you love the country, you just

can't stand the government, get it straight." he quoted mark twain to me, "loyalty to the country

always, loyalty to the government when it deserves it." it was an essential distinction i had been

neglecting. and then he had to reach out and grapple with the violence, but he did that with all

the people around him. second world war vets and all, on medical disabilities and all drunked

up. the house was filled with violence, which ammon as a pacifist dealt with every moment,

every day of his life. he said, "you've got to be a pacifist." i said, "why?" he said, "it will save

your life." and my behavior was very violent then and i said "what is it?" and he said, "i couldn't

give you a book by gandhi, you wouldn't understand it. i can't give you a list of rules that if you

sign it, you're a pacifist." he said, "you look at it like booze. you know alcoholism will kill

somebody until they finally get the courage to sit in a circle of people like that and say, "hi, my

name's utah, i'm an alcoholic" and then you can begin to deal with your behavior. see, and

have the people define it for you whose lives you've destroyed." he said, "it's the same with

violence. you know an alcoholic, they can be dry for twenty years, they're never going to sit in

that circle and put their hand up and say, "well, i'm not an alcoholic anymore." no they're still

going put up their hand and say, "hi, my name's utah, i'm an alcoholic." it's the same with

violence. you've got to be able to put your hand in the air and acknowledge your capacity for

violence and then deal with the behavior, and have the people whose lives you've messed with

define that behavior for you, you see. and it's not going to go away, you're going to be dealing

with it in every moment and every situation for the rest of your life." i said, "okay, i'll try that."

and ammon said, "it's not enough." and i said, "oh." he said, "you were born a white man in

20th century industrial america, you came into the world armed to the teeth with an arsenal of

weapons. the weapons of privilege, racial privilege, sexual privilege, economic privilege. if you

want to be a pacifist, it's not just giving up guns and knives and clubs and fists and angry

words, but giving up the weapons of privilege and going into the world completely disarmed.

try that. that old man's been gone now twenty years, and i'm still at it, but i figure if there's a

worthwhile struggle in my own life, that's probably the one. think about it. i'd always wanted to

write a song for that old man. he'd never wanted one about him. he was that way, but

something mulched up out of his thought, his anarchist thought. anarchist in the best sense of

the word. oh, so many times he stood up in front of federal district judge ritter, that old fart,

and he'd been picked up for picketing illegally. and he'd never plead innocent or guilty, he

plead anarchy. and ritter would say, "what's an anarchist, hennacy?" and ammon would say,

"why, an anarchist is anybody who doesn't need a cop to tell him what to do." kind of a

fundamentalist / anarchist, huh? and ritter would say, "but ammon, you broke the law, what do

you have to say about that?" and ammon would say, "aw judge, your damn laws, the good

people don't need them, and the bad people don't obey them, so what use are they?" well, i

had lived there for eight years, and i watched him, mainly watched him, and i discovered

watching him that anarchy is not a noun, but an adjective. it describes the tension between

moral autonomy and political authority, especially in the area of combinations, whether they're

going to be voluntary or coercive. the most destructive, coercive combinations are arrived at

through force. like ammon said, force is the weapon of the weak.

candidacy

mark twain said those of you who are inclined to worry have the largest selection in history.

why complain? try to do something about it. you know it's going on nine months now since i

decided i was going to declare that i am a candidate for the president of the united states. oh

yes, i'm going to run. shopped around for a party. well i looked at the republicans. decided

that talking to a conservative is like talking to your refrigerator. you know, the light goes on,

the light goes off, it's not going to do anything that isn't built into it. and i'm not going to talk to

a conservative any more than i talk to my damn refrigerator. working for the democratic party

now, that's kind of like rearranging the deck chairs on the titanic. so i created my own party,

it's called the sloth and indolence party. and i am running as an anarchist candidate in the best

sense of that word. i have studied the presidency carefully. i have seen that our best presidents

were the do-nothing presidents. millard fillmore, warren g. harding. when you have a president

who does things, we are all in serious trouble. if he does anything at all. if he gets up at night to

go to the bathroom, somehow mystically trouble will ensue. i guarantee that if i am elected, i

will take over the white house, hang out, shoot pool, scratch my ass, and no do a damn thing.

which is to say, if you want something done, don't come to me to do it for you. you've got to

get together and figure out how to do it yourselves. is that a deal?

bum on the road

well, i'd sing one for frying pan jack, who's alive, and the oldest of the old, out there in albany,

oregon. frypan jack settled out off of the trains as a great tramp. he got scared. he always told

me that if i get afraid to walk into a railroad yard, a makeup yard, it will be time to quit. he

used to carry a spike ball handle in the end of his bed roll. balloon he called it to fend off the

ne'er do wells, but you know the way it's gotten to be on the skids now, young mean drunks

and drug money, and so they prey off the old poor down under the railroad bridges. and so

they tend to settle out and stay in one place where they feel safe you see. he feels safe in this

bar over in albany, oregon. if you want to find frying pan jack, that's where you look for him.

we shared a camp down there in oroville, at the foot of the feather river canyon comin' out of

keddie on the western pacific--keddie, up at the top of the canyon, still has a wooden water

tower--it's never been torn down, and you can still camp under it--anybody ever been there,

up in the high sierra? well it's beautiful. jack & i were in that camp, that's where he said to

me--y'know he'd been trampin' since 1927--he said: "i told myself in '27 'if i cannot dictate the

conditions of my labor i will henceforth cease to work.'" ha! you don't have to go to college to

figure these

things out, no sir. he said: "i learned when i was young that the only true life i had was the life

of my brain. but if it's true that the only real life i had is the life of my brain, what sense does it

make to hand that brain over to somebody for eight hours a day for their particular use on the

presumption that at the end of the day they'll will give it back in an unmutilated condition?" fat

chance! so he built that big montana bed roll, started piping the stem... panhandlin? you

know... head full of words and songs. he didn't write songs and poems, he found them, and

scattered them abroad, for people like me to find and put to work again. he was old enough

to remember the sway rods under the box cars, ridin? the rods. fry pan jack, "the two bums":

the bum on the rods is hunted down as an enemy of mankind. the other is driven around to his

club, is feted, wined, and dined. and they who curse the bum on the rods as the essence of all

that?s bad, will greet the other with a winning smile and extend the hand so glad. the bum on

the rods is a social flea, who gets an occasional bite.the bum on the plush is a social leech,

blood-sucking day and night. the bum on the rods has a load so light that his wing we can

scarcely feel. but it takes the labor of dozens of folks to furnish the other a meal. as long as we

sanction the bum on the plush the other will always be there. but rid ourselves of the bum on

the plush and the other will disappear.

make an intelligent, organized kick; get rid of the wasted crutch. don?t worry about the bum

on the rods, get rid of the bum on the

plush.

enormously wealthy

we, the american people are enormously wealthy, you know that? who owns all those trees in

the national forests? this is not a rhetorical question. we do. who owns all of that offshore oil

you read about in the newspaper, huh? we do. who owns all of those minerals under the

federal lands? we do, it's public property and all. but we elect people to go to washington,

who are those assholes? what have we gotten ourselves into now? they go to washington, they

lease off what we own, public property, to private companies to sell us back our own stuff for

the sake of a greasy buck. that's dumb.

mess with people

i brought my daughter, moragan belle, she was 11 years old. i brought her back east during

the summer. we traveled around a good bit, here and there. and again, it was the sort of thing

where she had never traveled with me and all. it was quite different, she's quiet. lighthearted,

but she doesn't need to be entertained all the time, she can really take care of herself. i wanted

her particularly to meet her god-mother, dorthea brownell of saratoga springs, whom she and

harriet, her sister. elegant victorian women who befriended me many years ago in saratoga

and always gave me a place to stay. they were antiquarians of the first order. antique women

of the first order. and it was delightful going to greenwich, connecticut while dorthea was in the

country because they had to give up the big house when harriet died. looking out the window,

seeing dorthea, who was 83 and moragan, my daughter, on the bench there, and watch

dorthea there start teaching her how to make lace, she's a wonderful artist who makes

beautiful lace. well, dorthea's in the hospital right now, i'm going to visit her on wednesday

before i go over to amherst, the pioneer valley. a fine, fine teacher. now you see, i'm a

constant source of embarrassment to my daughter. why are teenage kids so conservative? i

don't do that to them, we don't do that to them, do we? i mean, i act out a lot you see, and i

mortify her in public places and i don't mean to, but she sure gets mad at me. i carry things

around with me to kind of rag people. well, i wouldn't leave home without my cockroach. i

always have my roach with me. there's a rubber cockroach. it's a tramp roach. frypan jack

calls that a tramp roach. he gave that to me. he says, if you're poor and you haven't got any

money, you're out on the street and you're hungry, you go into a restaurant with this and you

put it in the bottom of a bowl of soup and then you eat down to it and you say, "aahck, what's

that!". and then you storm out and say, "i'm not going to pay for that!", and you leave. it'll save

you a lot of money. that little jewel will save you a lot of money. little feelers sticking out the

side of a sandwich. goll, you eat half of it, and say "look at that!" and leave it. in the hands of

an unscrupulous child, can you imagine what you could do with that in the lunchroom at your

school. you could put that in your jell-o mold. god, you know, and some monitor or teacher is

going to come by and say "aahck, look at that, what is that?". you can look at it and say,

"well, it's a cockroach". you've got to mess with people, day and night, you have to mess with

people. they just kind of sink into a chryonic torpor and they're never seen again. i have my

dice for people i don't like, gypsy fortune telling dice. i like everybody. those people who

knew me will tell you i try to get along with everybody, you know. but over the summer i had

some fairly serious heart problems, so i decided i couldn't afford to like everybody anymore,

you know. i went on a low social cholesterol diet. no more fatheads. and so i run into one of

them, somebody i don't like and i tell them i'm going to tell your fortune, get these gypsy

fortune telling dice. and i roll the dice and they're blank, there's no spots on them. and i say,

"goll, i hate to tell you this, but you don't have any fortune, no future. that's it for you." we

were in the grand union supermarket, getting some food over by greenwich or cambridge, one

or the other, with old dorthea brownell, moragan's godmother. now this is education. a little

kid was fussing at the checkout counter stuck in one of those baskets. it's the lights in those

places, make kids crazy. we all know that, don't we? well, and the kid was fussy and the

parents were ragging on the kid. and i've always nosing kids, and i get them to laugh and the

parents laugh and the checkout person laughs, and everybody's feeling marginally better about

the whole proposition. so i put on my nose. moragan started punching me in the sides, yelling

at me, "why can't you be normal?" and old miss brownell rapped moragan on her shin rudely

with her cane and said, "he is normal, what you meant to say is average." yeah, that's

education.

natural resources

i was invited to the state young writers conference out at cheeney which was eastern

washington university, and i didn't want to embarrass my son, you know. and i was going to

behave myself because i had to live there then, a chore. but i got on the stage, it was an

enormous auditorium. there were 2700 young faces out there, none of them with any

prospects anybody could detect. and off to the side of the stage was the suit and tie crowd of

people from the school district and the principals, and the main speaker following me was

from the chamber of commerce. well, something inside of me snapped and i got to the

microphone and i looked out over that multitude of faces and i said something to the effect of,

"you're about to be told one more time that you're america's most valuable natural resource.

have you seen what they do to valuable natural resources? have you seen a strip mine, have

you seen a clear-cut in the forest, have you seen a polluted river? don't ever let them call you a

valuable natural resource. they're going to strip mine your soul, they're going to clear-cut your

best thoughts for the sake of profit, unless you learn to resist, because the profit system

follows the path of least resistance, and following the path of least resistance is what makes

the river crooked." well, there was great gnashing of teeth and rending of garments... mine. i

was borne to the door screaming epitaphs over my shoulder. something to the effect of, "make

a break for it kids! flee to the wilderness!" the one within if you can find it. well, i wrote them a

nice letter though as i oozed out of the state, headed for nevada city. i sent it to their little

literary magazine. i respect kids. i love especially little kids. little kids are assholes, but they're

their own assholes, you see. when you grow up, you can be somebody else's asshole. we're

all in trouble...

heroes

ask a kid, "who are your heroes?" chances are they'll give you the names of made-up people,

huh. he-man, barbie. i don't understand it about heroes, it really bothers. what happened to

the time when heroes were flesh and blood people? you know, people like emma goldman, or

elizabeth gurley flynn, or mother jones, or big bill haywood, or babe ruth, joe dimaggio, great

boxers, you know, joe louis. grandparents, what's wrong with your grandparents being

heroes? see, my mother, she worked for the cio, she was a labor organizer, and she made

sure that we had appropriate heroes, flesh and blood people. she would clip columns out of

the cleveland plain dealer, a good labor paper in its day, and paste them in scrapbooks so we

could take it to school to share with our kids at the equivalent of show and tell. scrapbooks

are mainly full of clippings about bank robbers. she seemed to favor bank robbers. called

them class heroes. didn't understand at the time what she meant. i do now.

half a ghost town

i headed up the mountains i was going to take some backroads over to a ghost town called

jerome, arizona. well, it was half a ghost town, you know, i had gone up there to find

somebody very important to folk music in an odd way, an woman by the name of katie lee.

you know the name katie lee? well, she was a folksinger in the 1950's. you might recall an old

record called songs of couch and consultation. it was satirical songs about the psychiatric

profession. and she sang, wearing a tight dress, for the playboy clubs. she sang folk songs.

well, she had retired, disappeared into jerome, arizona and went to work, she was one of the

founders of earth first and wrote a lot of songs about saving the colorado river, a powerful

woman. well, i was driving through prescott, arizona on my way to jerome, driving down the

street and i saw a sign, a street sign that said gale i. gardner avenue. well, i stopped and i said,

"i know that man." i had met him 25 years earlier in montreal, canada. teradezon and i were up

there. teradezon with the smithsonian festival, and gale gardner was invited up to tell poems

and songs that he had made up years and years ago as a cowboy. well, i went to the museum

there, the charlotte hall, and i said to the woman behind the counter, "now mr. gardner

wouldn't happen to be alive still?" and she said, "oh yeah, he's 95 years old now, but he's in

the hospital and ailing, probably isn't going to come out." so i went over to the hospital and i

spent the afternoon with him. shrunk down in his wheelchair. well, he had been a small man

when he was alive. i knew him as a small man with a enormous white (?) and a silver-headed

cane. there he was, shrunk down in his wheelchair with his great domed head covered with

the big liver spots and his glasses, one sided blanked out, so he could barely see through it,

and the other lens magnifying a empty socket in a grotesque sort of way. the high desert sun

had given him over the years many small cancers on his nose and on his ears that had to be cut

away. he was visibly diminishing, right before your eyes, but there was still that pillar of youth

and energy inside trying to burst out in any way that it could still find. i sat on the floor in front

of his wheelchair, so that i could see his face, because he couldn't lift his head.

holding on

i was in chicago some years ago. i was invited to play at a nightclub. at a nightclub, can you

imagine that? can you see me at a nightclub? the old quiet night up on belmont street, across

from cliff raven's tattoo parlor. well, i went up there at three o'clock in the afternoon to the

quiet night because i was scared. i fought my way past the guard dogs, got up there, the

janitor had taken the garbage out. he was in the big hall by himself, just sitting under the

nightlight up on the stage. an older man, he was sitting there playing the moonlight sonata,

beautifully. quietly i stood in the shadows, he didn't know i was there. a great shock of white

hair standing back on his head. deeply inside the lines on his face. i looked closely and saw he

was just playing with the one hand, the other was a stump, off to about here. well, he began to

pound the piano with the one good hand, and in a rumbling baritone voice started to sing

"freiheit freedom" a song of the tileman brigade during the spanish civil war, the war that if

we'd gotten involved in, there might not have been a second world war. he sang "los cuatros

generales", the herama valley, white cliffs of vendeza, powerful music of the spanish civil war.

well, that was eddie belchowski. eddie belchowski had been a concert pianist, a brilliant

pianist as a young man, but he went and joined the abraham lincoln brigade and went to spain

to fight against franco and the fascists. crossing the eberal river, he got his arm blown off. well,

they put him in the field hospital on morphine, which turned him into a junkie for the next thirty

years of his life. he haunted the alleys of chicago, a mad poet, derelict, a drug addict,

alcoholic. he began to put himself back together, got the job with the quiet night so he could

practice the piano. richard harding was good about that. and not just to learn the songs of the

civil war, but he learned heiden and licht variations. he could play the bach shukan with one

hand, it was beautiful. his daughter, reina, just sent me recordings, tapes that he'd made for

her, that i'd never heard of him playing a whole classical reporitre on the piano with one hand.

chopin, that was his favorite. well, he taught me powerful things about endurance, about

holding on. i left chicago, a week later i got a call, it said eddie belchowski had died. so i sat

down and made him up a death song. a week later, i got a call from eddie. the first thing i

asked him was, "hey ed, where are you calling from?" well, he said he was calling from

chicago. i said, "hell, dead, or in chicago, it's all the same to me, fella." and a week after that, i

was back in the quiet night, sitting on a bar stool with eddie belchowski himself sitting across

from me. i had a chance to sing him his death song. he was amused. but it was just a while ago

that ed belchowski, at the age of 74 was found on the subway tracks in chicago. they just had

a museum show of his art and poetry and music and recollections from old comrades all over

the country and then i sang his death song.