Khe Sanh Veterans Association Inc.

Red Clay

Newsletter of the Veterans

who served at Khe Sanh Combat Base,

Hill 950, Hill 881, Hill 861, Hill 861-A, Hill 558

Lang-Vei and Surrounding Area

Issue 55 Spring 2003

Memoirs

![]()

In This Issue

Notes from Editor and Board

Incoming

Web

Briefs Short

Rounds

In Memoriam

A

Sprinkling Of Your Poetry

![]()

Articles In This Section

Vietnam the Sequel

Combat Engineers Where

Valor Came of Age

Squalls Between The Storms

Major George Quamo

by Steve Johnson

PUBLISHER NOTE: Stephen's article was slightly edited due to the constraints of space in the newsletter. If any member desires an unedited version, I will make it available to them.

Introduction:

Col. Warren Wiedhahn, USMC (ret), is a long-standing member of the 3rd Marine Division Association. For a few years now, he has been put-ting the word out on the tours to Vietnam that his company, Military Historical Tours, conducts. The first time I heard about it I thought, "Why would anyone want to go back there, followed by, "Why would I want to go back there?" I also dismissed it as being too expensive.

I'm not sure when the actual decision to look into it took place. It was more of a mental evolution from complete rejection of the idea to, who knows, it could be fun. It took two years to work up the nerve to send in the reservation and even up to a couple of weeks before leaving, I still wondered if I was doing the right thing.

A few, well-intentioned people I had mentioned the trip to gave me the old, "You need closure," accompanied by what they thought were very sincere looks of understanding and sympathy for the torment my soul has endured, for lo these many years.

I got closure right here! The term "closure" would indicate that there was some sort of gap in a certain train of events. There was no gap. A lot of my friends were killed. That's it! I got back in one piece. That's it, too! No gaps.

Initially, it was a matter of curiosity as much as anything. It's sort of like surviving a terrible car wreck and then going to the junkyard to look at the wreckage and marvel that you lived through it. A friend asked me, "How can you forgive those people for what they did?" "Those people" didn't do any-thing to me that I was not trying to do to them. I saw the Viet Cong as sneaky little back stabbers but where I was, there were very few of them. My opponent, the North Vietnamese Army, was a well-trained, well-equipped professional soldier trying not to die for his country by causing me to die for mine.

This is not to say that I condone, in any way, how the North Vietnamese treated US POWs. But if you research WWII in the Pacific, or Korea, or, in fact, inter-Asian wars through history, you will see that extreme cruelty towards prisoners seems to be a basic Asian trait. From what I have read, if I was a former POW, I imagine I would have some serious hatred for my captors, but that wasn't my experience, so I cannot relate to it. I hope the following is of some interest.

On 10 March 1998,1 began the long journey that would take me back to Vietnam, a place I never expected to return to. I arrived at the Buffalo, NY, airport at about 3:30 PM. There began the odyssey of a lifetime. Processing at Buffalo and the commuter flight to JFK Airport in New York City went like clockwork.

I was beginning to anticipate something going very wrong because, so far, everything was going too smoothly. I must have picked just the right time to fly. After only about three minutes, the shuttle bus pulled up and I got on for a fifteen-minute ride to the other side of the airport. I got off at the Cathay Pacific terminal and got quickly checked in. When I got to the waiting area at the departure gate, there were very few people there, too. I saw a group with Military Historical Tours hats and/or name tags on, located and checked in with Ed Henry, our tour leader, and then hung out until the flight was called.

Our first destination was Vancouver, BC, which is five hours away...two hours there for refueling and then thirteen hours to Hong Kong. A documentary film crew, Peak Moore Enterprises, was also accompanying us. Warren Wiedhahn had said that they have been involved in previous Marine Corps-related film projects and come highly recommended. I understand they are doing this on a freelance basis and have no financial backing. Their plan is to pro-duce a film on their own, then sell it to one of the cable channels like The Learning Channel or The History Channel.

There were a number of active duty officers from the Marine Corps University at Quantico. They were young, earnest, and very respectful. Some are students, but in name only, because they are all captains, majors and colonels. Those who were not students were instructors. Many of them appeared to be keeping journals and I suspect they may be required to do papers on their return.

Many of the young gentlemen from Quantico (hereafter identified as the YG from Q) were reading the book "Siege of Khe Sanh" that we were sent by MHT. The book also includes the actions at Con Thien, Cam Lo, Hue City, and Lang Vei.

We landed in Hanoi on Vietnam Airlines at about 3:40 PM having lost a time zone on the way. Hanoi airport is strictly no-frills. Customs was brisk, efficient, and humorless. Virtually no attention was paid to the baggage. The weather was surprisingly pleas-ant. It was probably around 80 with low humidity. We were staying at the Thuy Thien Hotel, which reflects the erstwhile French influence. The hotel is on a side street just across from a police building and as soon as we stepped off the bus we were besieged by street hawkers selling post cards, T-shirts, pith helmets, embroidery and various trinkets.

Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum

At 9:00 AM we went to see the Ho Chi Minh mausoleum and

museum. The mausoleum is quite imposing and, at the same time, rather stark.

It faces what would normally be a very wide boulevard but it's blocked off to

all but pedestrian traffic. Across the boulevard from the mausoleum is a

twenty-acre park, which is sectioned off by sidewalks. Within each section is

some kind of very thick, bushy grass, which is obviously not made to be walked

upon.

imposing and, at the same time, rather stark.

It faces what would normally be a very wide boulevard but it's blocked off to

all but pedestrian traffic. Across the boulevard from the mausoleum is a

twenty-acre park, which is sectioned off by sidewalks. Within each section is

some kind of very thick, bushy grass, which is obviously not made to be walked

upon.

The museum was very modern and clean, but quite sterile. One Vietnamese explained that a lot of the displays were more symbolic than realistic. In fact, most of them were not made up of artifacts at all, but were more stylized sculptures in tribute to this or that glorious people's cause. It seemed to me that the average Nguyen could care less about a lot of it. The almost god-like respect seemed a little forced. One thing I noticed, though, was that there were no undisciplined little brats swinging from the displays or racing from room to room. Kids stayed with mom and dad and behaved themselves.

After lunch we went to the People's Army Museum, which was shabby and tacky. Everything seemed to be overly dramatic and almost amateurishly done. Displays were very static, and, if they were lighted, half the lights were out. In the courtyard of the museum was a large pile of chunks of various US aircraft shot down in the Hanoi area. Some of the wreckage had signs describing how this very jet killed 430 little girls before being blasted out of the sky by one of the People's Heroes, or, that exact air-craft was flown by a notorious American criminal who met his miserable end at the hands of a courageous North Vietnamese air ace. There were also artillery pieces and various ordnance plus a NVA anti-aircraft gun just like Jane Fonda liked to work out on. I hit the sack about 10:00 and had no problem going to sleep.

After breakfast we loaded up to go back to Uncle Ho's mausoleum, this time to go in and view the body, which has been on display for several years. There was a long line of locals waiting to get in. We had been told that we would have to walk in single file with our hands at our sides. No hats. Nothing in our hands. No backpacks, cameras, or belt packs. No talking, no smiling, no laughing. If you had your hands in your pockets or did anything the guards thought inappropriate, they could order you out of the building.

I decided that I didn't want to play their game. Respect is one thing but in a communist society respect is not earned... it is forcibly required. He may be North Vietnam's Thomas Jefferson, but he was just a commie stiff to me. I stayed on the bus, and after everyone else got off the driver moved to a small side street.

The last time I saw our people they were in their own line away from, but in front of, the civilians. My immediate thought was that our group was being paraded for the locals. Guards were walking up and down near the civilians and talking to them. Maybe I'm a little paranoid, but I can just imagine that the civilians were being told that the American criminals had come back to show their new found respect for Uncle Ho and atone for their wartime atrocities. About 45 minutes later, some of the guys back from the mausoleum said they felt hostility. The guards pulled one of them out of line and made him empty his pockets. Then, they waved him on. No reason given, and you don't ask why.

The afternoon flight to Da Nang was uneventful until we landed. Let's just say it was about one fish- tail away from a crash. Sometimes ignorance is bliss

In Da Nang, it felt about twenty degrees hotter with high humidity. What appeared to be fog in the distance was not; that's how thick the air was. While getting our bags loaded into the buses, we just stood around and sweated.

Not far from Da Nang we stopped at Red Beach. This is a long stretch of

beautiful white sand beach where the 9th Marines made their amphibious landing

in 1965. They were the first complete, tactical ground force to touch Vietnam.

Girls dressed in the national costume called Ao Dai passed out leis and

flowers to the Marines.

beach where the 9th Marines made their amphibious landing

in 1965. They were the first complete, tactical ground force to touch Vietnam.

Girls dressed in the national costume called Ao Dai passed out leis and

flowers to the Marines.

We checked in at the Houang Duong hotel in Hue, which is very nice and very Asian. We toured Hue this morning and it was interesting, We went from point to point in chronological order as the battle for the city unfolded during the 1968 Tet offensive. Among the YG from Q are some TBS (The Basic School) instructors who have researched the battle thoroughly and came prepared to give a narrative as we moved around.

We then went to an area near the center of the city near the Perfume River that bisects Hue. Across the bridge that was about three blocks away was the ancient Citadel that became the focal point for the NVA attack. Just around the corner from where we were all standing was the old MACV (Military Assistance Command Vietnam) compound, which became the center of US activity and which is now a Vietnamese government building. We were told we could walk down and have a look at it and take pictures but to stay across the street from it. It probably would have been OK if there were only a few of us but with about sixty people pointing cameras, it only took about thirty seconds for an army guard to come charging out brandishing his AK-47 and give us the heave-ho. The level of paranoia concerning army or other government facilities is incredible. The idea that looking at, or taking pictures of a building is a threat of any kind is ludicrous. On the other hand, I think a lot of it is based on the concept of continuous intimidation. It seems very petty. I would imagine that the guard who chased us off probably got elevated to People's Hero after his courageous action against the running dogs of capitalism.

We stopped for lunch at a little hole-in-the-wall restaurant and somebody found two American women there. One, Judith Hansen, had spent a year in Da Nang as a "Donut Dolly" with the Red Cross in 1967-68. She said she worked mostly with Marines so we stood up and sang the Hymn for her. She got quite emotional. She was traveling with her sister. It was her first time back.

After lunch we toured the Citadel. Almost all the battle

damage has been repaired. Nearly every large city in Vietnam has a citadel,

which was the residence of the local king or warlord or whomever was in

charge. The Citadel in Hue, however, was the old imperial capital of Vietnam

and was built around 1810. Parts of the huge wall around it are now gone but

it was originally almost 2000 yards on each side. The Citadel was bitterly

defended by the NVA because it had become a symbol of the non-communist south

and the presence of the North Vietnamese flag flying over it was believed by

the NVA to destroy the Marines' and ARVNs' will to fight. It didn't work.

By pre-arrangement, it had been decided to let the ARVNs be the first troops to re-take the Citadel even though the Marines had taken tremendous casualties getting to it. It became clear though, that the only way the Citadel would be taken was by the Marines, so they went in. Again, by pre-arrangement, the RVN flag was supposed to replace the NVA flag flying over the Citadel, but when the Marines finally blasted their way to the flagpole, the US flag was "erroneously" run up. After a suitable amount of time went by, the "error" was noticed and the South Vietnamese flag replaced the Stars and Stripes.

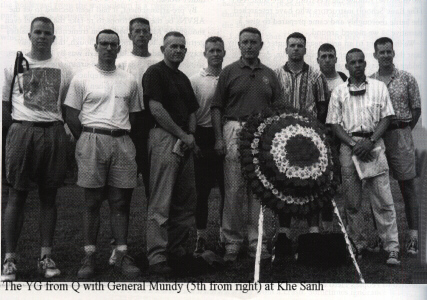

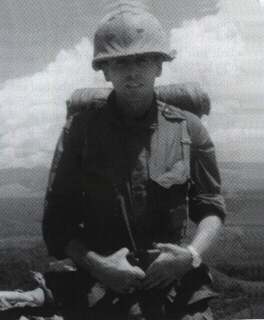

Ed Henry had told General Mundy that I had, for personal reasons, brought my bagpipes to play at Khe Sanh. There was already a plan for a memorial service there during which a tape of the Marine's Hymn and Taps would be played. The General asked me if I would play Amazing Grace after that. I had not planned on playing in front of the group and told him, but I said I'd give it a try as long as he didn't expect too much. I think he thought I was some kind of ringer from Glasgow.

After breakfast, we bussed north through Quang Tri Province. Even though I had patrolled out of Quang Tri when I was in Echo Company, 3rd Recon Battalion, there was nothing left of the huge base that had been there. It had been swallowed by a string of shantytowns and markets, except for the airstrip which is still being used.

We piled our luggage in the lobby and immediately reloaded the busses for the trip to Khe Sanh. Its 60 Km of bad road but there is an effort being made to improve it. There is virtually no heavy equipment to be seen except a few beat up dump trucks. Everything is hand labor and much of it by women.

As we got closer to Khe Sanh, the mountains looked bigger than I remembered. Many of the lower mountaintops are being blasted away for rock and gravel to use on the road. There has also been massive slash and burn agriculture practiced here for at least twenty years. The jungle that used to cover these mountains is all but gone, replaced by scrub brush and small trees. There still is lots of elephant grass, though.

First, we went to Lang Vei where the Special Forces camp was overrun by NVA tanks that many in the upper echelons said didn't exist. Some of our recon teams had reported hearing noises that sounded like tanks near the Laotian border. "Harrumph," said the brass, "there are no roads that will support tanks there!" Well, the noises were coming from Laos where vehicles could be used with relative impunity. When it came time to attack Lang Vei, the NVA used the Russian T-76 amphibious tank to ford the river that makes that part of the Laos/Vietnam border, drove east on Route 9, and squashed Lang Vei.

There was a lot of controversy then about why the Marines at Khe Sanh didn't send help, but it was the right tactical decision. Khe Sanh supported Lang Vei during the attack with all the artillery and other resources it had while under artillery attack itself, but a ground force would have been annihilated. If we had come down Route 9, there were hundreds of places to ambush us. If we came cross-country, it would have been the same. Either way it would have taken many hours and it was night. A reaction force would have lost hundreds to save a few dozen.

We had bag lunches at Lang Vei. It was extremely hot and airless. After lunch, we headed back up Route 9 to Khe Sanh. I knew that where the base had been is a coffee orchard now so I didn't expect to be able to see much. To my surprise, most of the trees were no taller than shrubs and they were in random patches. Not having trees overhead made it possible to "see up and out." It was the least altered of all the former bases we went to. Had it been allowed to grow over, it would have been covered with 30-foot trees and we would have seen nothing. This way, the lay of the land was clear and it was possible to get somewhat oriented.

Nothing is left but the general trace where the airstrip was. There is a badly deteriorated monument there that tells about the 10,000 Americans who were killed or captured by the glorious heroes of the People's Army. Everybody got a good laugh out of it. In the distance to the north was the ridgeline with Hills 950 and 1015. Hill 950 was the radio relay station called Rain belt Bravo. Because of the mountainous terrain in the Khe Sanh area, we rarely were able to communicate directly with the base.

There was a small detachment of Marine communications people there, and they often had to fend off attacks from the NVA who occupied the entire remainder of that ridgeline. It was the first thing I saw every morning as I came out of the Sergeant's hooch. Due to the humidity, it was very hazy but to the west I could just make out Hill 881 South. The other outpost hills were lost in the haze.

The base was abandoned shortly after the Marines made a Herculean effort to keep it during the Siege. It was bulldozed flat to keep the NVA from making use of it. By using a little dead reckoning, I think I got to within 100 feet of my old company area Bravo Company, 3rd Recon Battalion. I collected a baggie of that unmistakable red dirt that predominates in the Khe Sanh area. After I got to where I thought I was closest, it really hit me as to where I was. Standing on that red dirt looking at the 1015 ridgeline, in that heat, and humidity, and stillness...it seemed like I had been there just last week.

The YG from Q were trying to be everywhere at once. They have studied and know this battle probably better than those of us who were here at the time. To have the opportunity to walk this ground and see the terrain features and landmarks was literally an opportunity of a lifetime for them. I turned twenty-one again while I was here. As I looked around the area, it was like playing a video in my head. I could see every building and tent and smell the diesel and aviation exhaust fumes.

Facing north and mentally scanning from left to right, over beyond the mess tent is the Charlie Med station just off the helicopter taxi pad. That's the last place I saw Garry Tallent. It was the day before my 21st birthday and his patrol, Primness, had just flown out on a pair of CH-46 helicopters. They inadvertently landed right on top of a NVA unit what we refer to as a "Hot LZ" — which shot the chopper up and hit Tallent and the chopper door gunner. We were on the helo pad because we were waiting to be inserted into our patrol zone by the same helicopters. I thought the choppers were returning to pick my patrol up, but they were moving unusually fast. The lead chopper landed hard, and corpsmen from Charlie Med ran into it with stretchers. I was still thinking that maybe somebody had taken a bad fall or something but then they came out with Garry, blood all over, and I was hoping he was only unconscious.

The immediate reaction from my team was that one of them cursed and flung his rifle down on the helo pad. I barked at him to pick up his rifle and get a grip. We were just minutes away from possibly going into the same kind of situation, and I didn't need anyone who wasn't concentrating on the mission. Tallent had been my radioman on a number of patrols. Even when things got nasty, he was always smiling about something.

The helicopter his patrol had been on was shot up a bit so another one took us right out to our patrol zone. It wasn't until we came back almost a week later that we found out he had died. Because of the time delay involved, it didn't quite sink in. It was just that he wasn't around anymore.

Now, in my mind's eye, I'm looking at the regimental command post with its underground combat information center. Beside it is the watchtower that is manned at night, mainly to listen for the "poomp" of a mortar, or the deeper "boom" of artillery being fired at us from the hills. Rockets were harder to hear but if it was very still they made a sharp "Ssssssh" when they were launched and sometimes at night you could see the flame of the afterburner. The sentry had a hand-cranked siren that was the in-coming alarm that sent us scrambling for the bunkers. Rockets, especially, move very fast and the screaming noise they make is a real motivator to find a hole to crawl into.

Across the road and down to the right a bit, I see the tiny PX that never had much in it and next to the PX was the post office. Then comes our company office followed by the two rows of hooches and squad tents that house the company. The last hooch down in the row next to the road is where we sergeants lived. We have two-thirds of the hooch and company supply has the rest. The next area down is Engineers, I think. Back on this side of the road is the shower tent. A crude affair, but better than nothing.

Going to the shower tent during the monsoon was always an adventure. There were two ways to do it. One was to go more or less fully dressed in the filthy utilities you had worn for days on patrol. The problem was that after you got squeaky clean from your shower, you had to wear the same foul rags back to the hooch unless you brought a clean uniform with you. If you did, the rain hammered down so hard that your clean, dry utilities were soaked and mud splattered by the time you got back to the hooch. Raincoats were nonexistent and most ponchos were full of holes and offered only minimal protection.

The other way to go to the shower tent was the Marine way. Usually we just put a towel around our waist, stepped into our shower shoes, and strolled across the road. We would arrive drenched and shivering from the cold. Some, to keep their towel dry, just rolled it up under their arm and walked over in their birthday suit. There was absolutely no need for modesty. The best part was in returning to the hooch. Wet shower shoes are slippery and there was mud everywhere. Watching people exit the shower tent was almost a spectator sport because a large number of clean people wound up prone in the mud and rain when they slid out of their shower shoes. Of course, that meant another shower. Sometimes in the monsoon it rained so hard we just stepped out of the hooch and took a "natural" shower on a wooden pallet placed there for that purpose.

There was quite a bit more to the base than that, but it's about all I ever saw. We were off base on patrols so much that when we were here, the time was spent maintaining bunkers and equipment and preparing for the next patrol. I can see the bunkers between the tents and I can see the one where "Doc" Miller, Scribner, Rosa and Popowitz were killed. Khe Sanh was taking a lot of in-coming rockets that day in January of 1968, and most of my platoon was in that bunker. I had, only a few weeks before, been transferred to the newly formed Echo Company, 3rd Recon, that was going to be operating out of Quang Tri.

A Russian 122mm rocket is 4_ inches in diameter and about six feet long. Two thirds of it is rocket motor and the rest is high powered explosives. One of them came right through the door of the bunker and detonated inside. They weren't just killed...they were torn to pieces. One of the guys trying to dig the wounded Marines out of the bunker said later that all they found of Scribner was his helmet with part of his skull still inside. He said the rocket must have gone off in Scribner's lap. They knew it was him because he had written his name and blood type on the helmet cover. Besides those four killed, everyone else in the bunker was wounded, some of them horribly.

I didn't know about that until a couple months later when the Siege was over and what was left of Bravo Company was brought down to Quang Tri where the rest of the 3rd Division was. Those of us who had come from Bravo went to see them and it seemed as if there was hardly anyone left. I talked to one of the sergeants, Dennis Herb, for a while and he filled me in on who from my platoon had been killed or wounded and medevaced out. I think there were only seven or eight of my platoon left in the company.

We didn't stay as long as we had intended. It was too heartbreaking to stand among the tatters of the mighty Bravo Company, 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, USMC.

Most of the nearly 40% of casualties they took were not sustained facing the enemy. It was often due to the company's geographical position on the base. Any incoming that was fired at Charlie Med or the ammo dump that went wide either way, landed on Bravo. Any incoming fired at the regimental CP or the airstrip that went short or long, landed on Bravo. The company area became known as the V ring (as in the center of the target). After the Siege began, patrols outside the base were terminated, I don't think a Recon Marine ever fired a round at the enemy. But, that was when they took the majority of casualties. All they could do was dig their holes deeper.

Finding out that people I thought were alive had been killed three months before stunned me. Since I hadn't been there when it happened and hadn't seen them in quite a while, there was not the same sense of immediate loss. They were just gone and there was nothing to be done about it. I began realizing that maybe a part of the reason for making this trip was because I never got to mourn those guys.

All of this flashed through my mind in a matter of seconds. I was glad I was alone. This was tougher than I thought. My original intent was to try to get as close to the company area as I could and, very privately, play "Amazing Grace," the "Marine's Hymn," and then "Taps" on my practice chanter. The practice chanter is not much more than a fancy flutophone and it's used for fingering practice for the bagpipes. The bad part is that it doesn't sound like much. Just sort of a muted buzzy sound. I had debated with myself whether to bring the bagpipes themselves and I finally decided that if I had them with me, at least I would have a choice. I deliberately did not bring the drones... those three big pipes that stick up over the left shoulder. I had correctly assumed our bags would get pretty rough treatment on this trip and I just didn't want the drones damaged. It was enough that I was risking damage to the pipe chanter, air bag, and blowpipe. However, the drawback to playing the pipes instead of the practice chanter is that the pipes were meant to be heard over the noise of battle, so if I did play them it would not go unnoticed.

Why would I care if anyone heard me? Isn't "Amazing Grace" an appropriate tune to play on such an occasion? The problem was that I had attempted to play "on the bag" only a few times and did badly to say the least. I had never gotten all the way through any one tune. Playing the practice chanter is not much more than blowing into a plastic tube. But playing the bagpipes brings several new dimensions into play. Imagine rubbing your stomach, patting your head, whistling a tune, and marching in step all at the same time, with almost no practice. Then, imagine doing all that at a very special event, in front of sixty people, with no practice at all. When General Mundy asked me in Hue if I would participate in the memorial service I was flattered to be asked, while at the same time knowing I couldn't do it. It was hard enough just being here, let alone being part of the program. After the group had some time to look around, General Mundy assembled us and began the memorial service by presenting a Purple Heart medal to Rob Sutter, a former Marine captain, for his brother who had been killed here. That was followed by comments from the General and Alan McLean, a former Marine 2nd Lieutenant who had lost both legs and is now an Episcopalian Priest.

I was pacing around behind the group trying to calm down. I kept trying to wet my lips but I was so dry I virtually couldn't spit. A recording of the Marine's Hymn and Taps was played and, finally, General Mundy gave me a nod. If I'd had any confidence at all that I could do this, I would have just launched into "Amazing Grace" from behind the group. Remember...! had never played a complete tune on the bag and I had only attempted that in front of my pipe instructor.

Even

though I knew it would break the mood a little, I felt I had to explain that

this was a maiden flight for me so I started saying something like, "I

should tell you all that..." and they all turned around! With everyone

looking at me I instantly felt I was going to make a damn fool of myself. This

was a very personal and serious occasion for me and the enormity of it kind of

overwhelmed me. I had to stop and regroup for a moment. I then went on to

explain my situation and that if they would bear with me, I'd give it a shot.

Even

though I knew it would break the mood a little, I felt I had to explain that

this was a maiden flight for me so I started saying something like, "I

should tell you all that..." and they all turned around! With everyone

looking at me I instantly felt I was going to make a damn fool of myself. This

was a very personal and serious occasion for me and the enormity of it kind of

overwhelmed me. I had to stop and regroup for a moment. I then went on to

explain my situation and that if they would bear with me, I'd give it a shot.

It must have been pure adrenaline, but I did it! it wasn't perfect, but it was "Amazing Grace!" Ordinarily, a solo piper plays that tune Through twice. When I got to the end of the first rendition, I didn't dare do it again. I instantly felt 20 pounds lighter. I had amazed myself. As I was putting my pipes away all the Khe Sanh veterans came over and patted me on the back or put their arms around me and said it was great. There wasn't any phoniness about it either. They really meant what they said. I couldn't see very well right then, but I think it was Rob Sutter who put his arm around me and said, "Thanks, brother." It was well worth all the mental wear and tear I had put myself through.

I felt completely dehydrated. I bought two cans of pop from a little girl not much bigger than her cooler and chugged both of them down. That was it. I had done what I came to do and for the rest of the trip I would just be Joe Tourist. There was a drawback, however. Now everyone was convinced that I was just too modest and was, in fact, the pro from Aberdeen!

The sun was heading down as we left Khe Sanh. My only regret was not being there at sunset so I could hear the Rock Apes hooting in the hills. Rock Apes was the generic name we gave to any monkey we saw. The most common were a gibbon-like animal that traveled in groups through the treetops as easily as we walk down the street. Every evening, just at sunset, when we were in the bush on missions, the Rock Apes would settle into their roosts and begin howling. It was a long, drawn out "whoowhooo-whooo" that gradually went up in pitch. Imagine the din when thirty or forty of them were going at it. This chorus would last about fifteen minutes, and we could sometimes hear it coming from several locations around us. When on patrol, the closer we set in at night to one of these groups without spooking them, the better off we were. The Rock Apes did not hoot if anything unusual was going on, so a lot of monkey noise nearby meant we could relax just a little.

The return to Dong Ha was long and quiet. I checked out the room and noticed that the beds were clean and freshly made but that was the extent of the amenities. The waitresses and other staff were in spotless white Ao Dais and were very efficient. They probably hadn't seen this many people at once in a long time. The food was fair but there were a couple dishes I noticed hardly anyone touched. We just weren't sure what it was. About 9:30 I dragged myself up the stairs, got buzzed by a bat in the hall, and hit the sack.

I decided to take the day off because the group was going to two or three locations that I had never been to when I was here thirty years ago. Just by coincidence I found out that three other people were staying back to go to the Lew Puller School in Dong Ha to deliver pens, pencils, etc. Puller was the son of Marine Corps legend General Lewis Burwell Puller who, while in Vietnam, lost both legs, as well as other serious wounds. Because of who he was, or rather, who his father was, there was tremendous pressure for him to be THE SON OF CHESTY PULLER! His wounds brought his Marine Corps career to a crashing halt and he fell into various addictions and mental problems. One thing he accomplished, though, was to generate considerable donations to an organization called the Vietnamese Memorial Association that was formed to build schools in Vietnam. Because of his efforts, the first of these schools was named the Lew Puller School and there is a bronze plaque with his likeness on it near the front door of the school.

The other three people visiting the school had known Lew as a kid and teenager. This was a special visit for them. Ed Henry had told me that a visit to the school was planned, but I wasn't sure if it necessarily meant the whole group was going. Since I was staying back and had no other plans, I asked if I could go along. I had about ten pounds of pencils, pens, and crayons with me. After a ten minute kamikaze ride we arrived at the school. The cabs pulled into the schoolyard and right up to a flagpole. The school is a masonry, two story, L shaped building with about a two-acre schoolyard. The hallways are external, much like many buildings in the southern US.

One of the group had the headmaster's name, a Mr. Quoc. Somehow, he thought it was pronounced "duck." Two people came out and he asked for Mr. Duck. They obviously didn't speak or understand English, and they had no idea what the word "mister" meant, so the word "duck" had no relevance either. After a few minutes of asking into the whereabouts of Mr. Duck, the desk clerk/spy came out with a lady who turned out to be Mrs. Mat, the assistant headmistress. She understood just a little English, didn't know anything about Mr. Duck, but invited us to her office. It was about ten by twelve feet and had little in it aside from two tables arranged in a T shape with chairs around them. As we sat down, a thermos of green tea was produced and poured into a china teapot, and, from there, into tiny china cups. We toasted, I don't know what. Our spokesman kept trying to explain our presence in his horrible French, which the younger Vietnamese do not speak.

Finally, a couple of us just opened the bags of stuff we'd brought. I think it was only then that Mrs. Mat realized why we'd come. She was very happy to see the pencils and pens and when she saw the two cigar boxes of crayons I'd brought she appeared very surprised and grateful.

Someone began beating what sounded like a bass drum and all the kids came pouring out into the schoolyard. There are two sessions, morning and afternoon, for grades one through six and the total enrollment is 374. Most of the kids wear the school uniform of white shirt and blue pants or skirt. They immediately fell into ranks. For you tactical types, it looked like battalion in column with companies on line) and began a few simple exercises to the beat of the drum. The littlest ones were in the middle and just kind of jumped around. Then, at a certain signal on the drum, they all went screaming back into the school. I had gone down the hall and around the corner to videotape them and before I knew it, my position was overrun and I was hip deep in munchkins.

After things calmed down, they were herded back to their classrooms and we were shown the school's computer room. There were six or eight rather used looking computers someone had donated. Like our hotel, there does not seem to be any electricity during the day so I don't know what good they were. We were introduced to the computer teacher, so I guess they use them, but I don't know when. On the way to the school, we had passed a large intersection where two or three blown-up American tanks are on display. They are just rusted hulks with weeds growing up around them with a sign dedicated to the Heroes of the People's Army.

On the way back to the hotel, the guy in the cab with me said something about stopping to take a picture. I said I would rather not because my ankle was quite sore (it was) and he said OK. In my mind, though, I didn't want to stop because I knew what our tanks look like and didn't need a picture.. It's probably just me but I think any show of interest in something like that is demeaning. It is a monument to the actions of communist forces that almost certainly resulted in American deaths. Remember, even though we are now in South Vietnam, we are in communist South Vietnam and are officially the bad guys...the enemy...the defeated enemy. Except for the South Vietnamese who know better, the people here see us as returning survivors of a beaten invader.

Back at the hotel, I took a short nap and then went down to meet the other three for lunch. While I was lounging in the lobby talking to the desk clerk/spy, a group of about a dozen doctors, nurses, and EMTs from the States checked in. They were in Vietnam holding clinics in several rural areas. I'm not sure who their sponsor was but there are lots of groups like them working all over the world.

About 4:30 the rest of our group came in, tired and dusty. At 6:00 we had an audience in the restaurant with a Mr. Ky. He was a company commander at Khe Sanh, an NVA company commander, that is. Now he is the 2nd to the top dog in the Dong Ha district of Quang Tri province. He arrived with a small entourage including the ever-present Political Officer who is the watchdog at official functions. The Political Officer introduced Mr. Ky to us and made some welcoming remarks. By now it was dusk outside and the electricity had not yet been turned back on so the only light was from light stands put up by the film crew.

Through one of our two interpreters, Cheong, (pronounced Chee-ung) Mr. Ky gave us the party line about letting the past go and work on the future. Blah, Blah, Blah. About then the electricity came on. There was some lengthy discussion between Mr. Ky and Cheong but before any translation was made, Thrinh, (pronounced Cheen), our other interpreter said that Mr. Ky would now take any comments or questions about the action at Khe Sanh. Apparently that was the wrong thing to say because the Political Officer immediately jumped in and there was more discussion in rapid fire Vietnamese. Then Cheong said that because Mr. Ky had another pressing engagement, he would have to be leaving soon and it would be more productive to talk about the future. Afterward, there were several people honestly wondering if we would see Trinh again. Two former Viet Cong who had been in this area were introduced. One was pretty normal looking. The other guy looked like a pretty tough nut.

A couple of people made a few comments and General Mundy made a few comments. Then Mr. Ky and entourage made their exit. The whole thing was pretty much a dog and pony show, but I guess that's politics. We were all ushered out of the restaurant so they could set up for dinner. While we were waiting, the power went off again and the waitresses passed out candles. That probably happens a lot. After about thirty minutes the power was restored and we had dinner. Power went out again at 9:00.

Trinh showed up for breakfast, alive and well, so I guess he didn't dishonor his family too badly. We left the hotel for the bus ride back down to Da Nang but on the way, we stopped at the Puller School. This was obviously the planned visit I wasn't sure about. They trooped all the kids out for the aerobics demonstration, but it wasn't like yesterday. That was much better. We stopped at a few sites in the Dong Ha area and then headed south.

On the 20th, it would be Colonel Meyers' 50th anniversary. His wife was here on the trip and they will be re-married by Father McLean. Colonel Meyers asked me to play "Amazing Grace" for them at their wedding. That was also the anniversary of their son's death. Another no-pressure situation. As mentioned before, I think some people think I know how to play bagpipes. They were soon to be shown the error of their thinking.

Tomorrow the group would be in An Hoa. I hadn't planned on going but Colonel Christy hinted that he would very much like "Amazing Grace" played there. He lost 100 Marines there in an ambush because of a screw-up at battalion HQ. He wanted me to play the "Navy Hymn (Eternal Father)" but there aren't enough holes on the chanter to cover the octaves needed to play it. Colonel Christy didn't mention my pipes for An Hoa, so I didn't bring it up. We cycled over to the Military Museum. It was sometimes difficult to keep a straight face after reading the ludicrous captions on most of the photos. I saw the same photo in three different places in the museum with a different caption on each of them. The picture was of an American GI leaning against a tree with his head down as if he was taking a breather. One caption had him "trapped in a valley," another had him "retreating before the People's Army," and the third had him, "lamenting the crimes he had committed."

Many items on display were nothing more than propaganda posters showing smiling NVA distributing rice to the oppressed people of the American- backed puppet regime of the South. There were large maps of battles where the NVA killed "thousands" of Americans. Oddly enough, Khe Sanh and Hue did not appear on any map and there was no other mention of either place. One photo showed two US medics obviously treating a Vietnamese heat casualty and one of them was holding a canteen to the victim's mouth. The caption explained, "Two American criminals were administering water torture to a brave patriot." Yet another showed a number of NVA looking over several bodies lying on the ground. The caption read, "Our brave warriors examining some of the 1000 Americans killed in May 1965." In May of 1965 I'm not sure there were much more than 1000 Americans in all of Vietnam, let alone that many killed in one action. The best part was that all the bodies in the photo were clearly Asian! The photo contradicted the caption. I guess it must be a case of "don't believe your eyes, believe what you're told."

I took a nap and then hung out in the lobby until 6:30pm when I went with Father McLean to the hotel restaurant to help him set up for Colonel and Mrs. Meyers' wedding. Alan suggested I pipe them in to the "Marine's Hymn" and then at a certain point play "Amazing Grace." Despite how things turned out at Khe Sanh, I didn't have any more confidence in myself and was rapidly getting very nervous. I had not previously learned the Hymn and had taught it to myself on the practice chanter only over the past couple of days.

The restaurant was not air conditioned. My hands were very sweaty. My fingers kept sliding off the holes on the chanter and I messed up both tunes. I was probably trying to hold the chanter too tight. Later, the Meyers' and others said I did a good job and the missed notes didn't mean a thing, but it didn't make me feel much better. I didn't plan on doing any command performances. With my nearly total lack of experience as a musician, to have my first two gigs be a 30th anniversary memorial service and a 50th anniversary repeating of the vows was like a passenger trying to land a 747 after the pilots both have heart attacks.

The Meyers' wedding was held under "field conditions," but otherwise went well. The hotel provided two huge flower baskets and a cake and had made up a sign congratulating them on their anniversary. The English spelling was very creative, but they tried hard. The hotel and restaurant staff was there for the service and knew what was happening, but they all looked a little confused at our bizarre rituals. Tomorrow we'd fly to Saigon.

Only two more nights in country after that. We stayed at the Saigon Star Hotel. Another very nice hotel. Saigon is very different than any city we've seen so far. Except for the signs in Vietnamese and the obvious Asian population, you would think you were in a typical large European city. Wide streets and boulevards, relatively clean with a lot of space devoted to parks.

During a farewell dinner that night, there was a single table set with a black table cloth, a plate with a little bit of rice on it, and a vase with a rose. The chair was tipped up as if it was being saved for someone. It represented the missing man.... those dead or unaccounted for. After dinner, there were several toasts and General Mundy was presented a marble plaque. The floor was then opened for any remarks and several people made very moving comments.

All in all, it was a memorable trip and MHT did a flawless job. I would highly recommend it to anyone and even if you weren't there during the war, it's a tremendous trip into a significant era of Marine Corps History.

Steve Johnson

*****

Marine Combat Engineers

At The 1968 Siege of Khe Sanh

The 35th Anniversary of the Start of the Siege

Story by

Bill Gay, Bruce Bell, David

Critchley, Frank Kledas,

Terry Parr, John Pessoni,

and Gerald Traum

This is a history of the part that 1st Platoon, A Company, 3rd Engineer Battalion (Combat), 3rd Marine Division played in the North Vietnamese Army Siege of Khe Sanh during the 1968 Tet Offensive. We had a great platoon. We are proud of what we did.

We paid heavily as many units did. At least eight members of our platoon were killed. So many were wounded that none know the final count. Several are disabled today from wounds and from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

We

write this history for each other, our fallen comrades, our families, the Khe

Sanh Veterans Association, at the urging of an older VA PTSD counselor who uses

this history to train younger counselors when someone says they were in the

Siege.

We

write this history for each other, our fallen comrades, our families, the Khe

Sanh Veterans Association, at the urging of an older VA PTSD counselor who uses

this history to train younger counselors when someone says they were in the

Siege.

As our reasons for writing this history increased, so did its length. We added background to help all families understand Khe Sanh. As each of us remembered more, we added more details. Skip over the background information if you already know it. Smile with us as you read the personal stories. We decided that the only truth that is absolute is that each of us remembers the truth differently.

The Khe Sanh Tactical Area of Operations

What Khe Sanh was can be succinctly defined by the titles of historical works authored by Chaplain Ray Stubbe of the 1st Battalion, 26th Marines ("The Valley of Decision" and "The Final Formation"); by writer Robert Pisor ("The End of The Line - The Siege of Khe Sanh"); and combat photographer David Douglas Duncan ("I Protest").

The Khe Sanh valley and surrounding mountains were

beautiful, settled by the Bru mountain tribes, Vietnamese villagers and French coffee plantations. Located in the

northwest corner of Vietnam about ten kilometers from North Vietnam and Laos,

the valley was an important logistics and invasion route for the North

Vietnamese Army when they invaded the South.

tribes, Vietnamese villagers and French coffee plantations. Located in the

northwest corner of Vietnam about ten kilometers from North Vietnam and Laos,

the valley was an important logistics and invasion route for the North

Vietnamese Army when they invaded the South.

Hundreds of US fighting men died and thousands more were wounded, as Stubbe states "because of Khe Sanh." Thousands of Bru and Vietnamese citizens and tens of thousands of NVA soldiers were killed and wounded at of Khe Sanh. The French had a combat base at Khe Sanh before 1954. Army Special Forces started operating in the area in the 1960s. Marines arrived in the mid-60s, building a combat base and defeating the NVA in the vicious fights to control the hills surrounding the Khe Sanh Combat Base (KSCB), what were later known as "The Hill Battles."

The US presence reached its peak in late 1967 and early 1968 when the 26th Marine Regiment held the KSCB and the Hills against attacks by two NVA Divisions. The NVA attackers probably outnumbered US defenders about 4 or 5 to 1, even though the 26th Marines were reinforced by the 1st Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, all types of Marine units including l/A/3rd Engineers, Army, Air Force, Navy units, and a South Vietnamese Army Ranger Battalion.

Route 9, a single lane road, connected the larger

Vietnamese cities and Marine bases in the east to Khe Sanh. It also connected

Khe Sanh to Laos. The Viet Cong and NVA damaged the eastern length of the

highway beyond use sometime in 1967, denying US forces the benefit of being

supplied or reinforced by road. The western length of Route 9 to Laos remained

open, enabling the NVA to supply and reinforce their units from the Ho Chi Minh

Trail. With Route 9 cut, the Marines at the KSCB and on the Hills had to be

supplied by air.

That was not too difficult when the Marine garrison numbered only about 1,000. US planes could airdrop supplies on the KSCB using radar controls from the coast near Da Nang, even when visibility fell to a matter of a few feet during the Winter Monsoon season. Supply by air became a real challenge when our strength grew to over 5,000. Supplying the Hills was a tougher job. The Hill defenders, and those who risked their lives supplying them suffered greatly.

The Siege Begins

The fiercely fought 1968 Tet Offensive started at Khe Sanh at the height of the Monsoon season. Close Air Support by fighter-bombers and helicopter gunships, and medical evacuation aircraft often could not help the defenders of Khe Sanh in those early days.

NVA artillery hit the main KSCB ammunition dump the very first time the NVA unleashed what became almost daily massive shelling attacks. The Lang Vei Army Special Forces camp near Laos and the few Marines with the Vietnamese militia in Khe Sanh village were quickly overrun by large NVA forces. NVA tanks, never before used by the NVA against US Forces, smashed through the wire at Lang Vei.

The Marines on the Hills defeated violent NVA attacks. The KSCB was also probed by NVA ground forces. With the Hills and the KSCB undefeated, the NVA used its overwhelming troop strength, artillery and rocket resources, and logistics capability to create the Siege of Khe Sanh.

The NVA relentlessly punished defenders of the hills and the KSCB with mortars, artillery, rockets, recoiless rifle fire and direct rifle fire for 77 days until early April, We all knew we could be hit at any time or crushed when an explosion collapsed a bunker or trench. Our normal human senses took on animal-like acuity. We moved like cats from one protective cover to another to minimize the chance of a being hit by a round we did not hear coming. But we heard most of them coming and tensely waited to find out if that round would wound or kill us, a friend, or a nearby stranger.

In April, the Marines broke out of the KSCB and the Hills, attacking the NVA. Many more Marines were wounded and died in these fights, part of Operation Pegasus. The 11th Engineers broke all records building about eighteen bridges and bypasses to enable Army and Marine ground forces to flood into the Khe Sanh area by road, and overland. More Marines were killed and wounded in engagements in the following months until the Marines departed in the summer of 1968. This departure permanently ended the US presence at the KSCB and on the Hills. Marine, Vietnamese, Army Special Forces and Army regular units continued to operate around Khe Sanh on a temporary basis inflicting great damage on NVA units while continuing to suffer casualties themselves.

Lightly equipped Combat Engineers such as 1st Plt A Co 3rd Engrs were always fighting alongside the Marine maneuver units. More heavily equipped Force Engineers, such as the 11th Engineer Battalion, were always working somewhere to keep supplies flowing to the Marine maneuver units.

Few Knew The Magnitude Of The Siege

From official government records, we know that more US bombs were dropped in defense of Khe Sanh than were dropped in some major theaters during all of World War II. Courageous Air Force and Marine cargo plane and fighter-bomber pilots and crews, and helicopter pilots and crews from all services kept our supplies, replacements, and close air support coming no matter how much NVA anti-air-craft fire was directed at them and no matter how many aircraft and men they lost.

Special US intelligence units in Thailand listened to NVA movements on sensors that a Special Navy anti-submarine warfare squadron, diverted from sea duty, dropped around us. That information helped Marine and Army artillery Forward Observers and Air Force Forward Air Controllers direct devastating fire on NVA units night and day when the NVA prepared attacks.

We recently learned from an article in Red Clay Newsletter, the Khe Sanh Veterans Inc. Magazine, that the Navy flight crews who dropped the sensors had to fly so low and slow they were decimated. Most of us crawling in Khe Sanh's red clay never knew these brave men were sacrificing themselves to help us survive.

The Joint Service effort and US technology that helped us win the Siege was impressive, but in the final analysis it was the individual Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines at Khe Sanh that held firm, enduring the worst artillery and ground attacks the NVA could deliver. Human costs were high for everyone. Stubbe recorded the names of about 600 US confirmed killed in action. The Charlie Med surgeons log shows they treated about 2,500 wounded in action.

Those numbers don't include all the wounded, and may not include all the dead evacuated directly off the Hills to the rear, the Navy fliers who perished dropping sensors, the pilots and aircrews from all Services shot down, the Special Forces and CIA operatives killed in Laos and North Vietnam while directing fire on NVA reinforcements heading for Khe Sanh, and others that we are just learning about. If we knew who all of those warriors were, the total of US warriors lost at Khe Sanh would be much higher.

Additionally, thousands of innocent Bru mountain tribe members and Vietnamese civilians were murdered by the NVA when the NVA swept into the area. US firepower probably killed many more of those that could not escape the area when we started bombing, or chose to stay in their ancestral homes. Official estimates of NVA casualties around Khe Sanh are about 15,000. Thousands more NVA died on the Ho Chi Minh Trail carrying supplies to the two reinforced NVA Divisions surrounding Khe Sanh.

The once green landscape around Khe Sanh became a barren moonscape from US bombs and US and NVA artillery. Huge amounts of Agent Orange herbicide was sprayed and has ruined the lives of many fighters and civilians on both sides. We've learned that tactical nuclear weapons were positioned for use in case US forces at Khe Sanh were in real danger of falling. Anyone who knows the terrain at Khe Sanh knows that everyone in the area on both sides would have suffered badly if tactical nuclear weapons had been used.

Presidential Recognition

Khe Sanh was declared one of the most significant battles of the Vietnam War. We now know that President Johnson had a scale model of Khe Sanh in the White House and was briefed almost daily on our ability to hold. It would be years before we personally understood the significance of having survived Khe Sanh. Khe Sanh was mostly just red clay to us. We saw it from a few inches off the ground. While we were there, we doubt any of us thought of Khe Sanh's strategic significance. For their dedicated efforts the defenders of Khe Sanh were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, which is equivalent to the Navy Cross, if it were an individual award.

After the fall of South Vietnam in April 1975, the NVA erected a victory monument at Khe Sanh attesting to the importance of Khe Sanh to their side. Today, the NVA monument is viewed by international tourists visiting the battlefields. Tourists unfamiliar with the many battles at Khe Sanh may believe the NVA victory claims. The US and Vietnamese forces who fought there know the truth: We won.

The Engineer Build Up

By military doctrine, one Combat Engineer Platoon normally supports one Infantry Battalion. We contribute our expertise with demolitions. We also have pioneer tool chests with axes, shovels, and chain saws. Marine Engineers normally leave these at a base camp.

Combat Engineers carry the same weapons and ammunition as the Infantry. Every Engineer also carries two or more twenty-pound Satchel Charges of explosives. The joke is that a Marine Combat Engineer is really only "a grunt with a satchel charge."

Our Combat Engineer Platoon, l/A/3, supported the entire Khe Sanh Combat Base. By doctrine, this mission normally would be assigned to a reinforced Combat Engineer Company, a force about five times larger than our platoon and much better equipped.

We were faced with doing the best we could with the meager resources we had. We radioed our company in Dong Ha once a day to report our dead and wounded and plead for replacements and supplies, but few came. We became more exhausted as our casualties mounted, but we never stopped working.

Exhausted men doing a great deal with few resources was the normal state of most support units at Khe Sanh. None of us were going to let anyone down on the KSCB, or on the Hills. In late Fall 1967, our platoon had less than twenty members. We sent teams on 1/26 operations, did mine sweeps and civic action projects in the village, blasted rock for the Seabees to use to improve the runway and roads and operated the KSCB water point. Life was not very dangerous, then.

Battle-weary Engineer veterans such as Cpl Gerald Traum, who fought in the fierce 1967 Hill fights, completed their tours and left for "The World." The rest of us recording this history were arriving. After Thanksgiving 1967, our platoon strength increased to over forty. We knew a big fight was coming, but we had no idea that fight would become the Siege.

Another Combat Engineer Platoon from C Company, 3rd Engineer Battalion arrived about the time the Siege started. We were so busy, we seldom saw them, and strangely, none of us recall what they did. We hope someone records their story. We know they must have been as busy as we were. Captain Bert Ranta arrived to coordinate all Engineer work with the regimental staff. Ranta lived with our platoon in a bunker with 2/Lt. Bill Gay and our platoon sergeant, S/Sgt Ronald C. Sniegowski.

From then on we cleared acres of fields of fire, built hundreds of meters of barbed wire fences, planted hundreds of booby traps and mines, retrieved tons of air dropped supplies that drifted into the minefields, cleared many dead NVA from the minefields, built bunkers, and miraculously kept the water point flowing. We also served as listening posts and reinforced perimeter positions at night.

We worked every day and almost every night in small teams. We seldom knew if our teams had a good or bad day until we returned to our bunkers. That is when we found out about our losses for the day. Some evenings were joyous and some sad. We were only with the units we supported for a short time before we moved on to another mission. Some units never realized we were Combat Engineers. This is why it is so important for Engineers to stay in touch. We were not part of a big family support group like an Infantry Company.

New Fields of Fire and Protective Fencing

In the fall of 1967 most of the perimeter around the KSCB did not have cleared fields of fire or good protective barbed wire fencing. In December 1967, Lt.Gay was talking to 1/Lt. Tim Reeves on the regimental staff about how the perimeter could be improved. Reeves took Gay to talk to Col Lownds about what could be done. Within a day Lownds ordered the Seabees to provide earth moving equipment to help us clear fields of fire, and ordered several Infantry Platoons to work with us to build new barbed wire fences.

The new fences, looking from the enemy side inward, consisted of a high double apron, then a wide empty space to prevent NVA Sappers (i.e., their combat engineers) from breeching more than one fence at a time. An extra wide belt of tangle foot fence, another wide empty space, a triple concertina fence, and another wide empty space before reaching the Marine trenches. Everyone worked hard. The Seabees welded pipes to the sledge hammer heads to replace the broken wooden handles we broke at record rates. We placed empty artillery shell canisters over the fence pickets to create a bigger target for the hammers. Everyone innovated. This Infantry, Engineer Team effort dramatically changed the KSCB perimeter in a few days. The vegetation that once came up almost to the old broken wire was removed. In its place was bare red clay and formidable fencing. The new perimeter protected most of the KSCB and the Special Forces FOB trench lines before the Siege started.

After the start of the Siege, it was too dangerous to clear fields of fire with the Seabee equipment. We did it by hand, burning grass with unused artillery powder bags, and cutting down trees with demolitions. We continued to help the Vietnamese Rangers, 1/9, and 3/26 improve their perimeters while they did a lot by themselves. We wanted very much to help the Hills, but there were not enough of us to be sent there too. We were proud of how much our efforts improved the KSCB perimeter.

Before the Siege, the only type of mines protecting the perimeter was the highly effective Claymore placed by the grunts. But they would not have been enough if wave after wave of NVA attacked. We added hundreds of "Bouncing Betty" and "Shoe Polish Can" anti-personnel mines, anti-tank mines, and innovative booby traps. Our booby traps were made to look like fencing material we left behind in the typical manner of US troops who had too much material. However each of those partially used rolls of barbed wire or abandoned steel stakes was booby trapped and set to explode if an NVA tried to crawl or charge through the fencing. At first, we were able to use the cover of the monsoon fog to hide us when we placed mines. When the weather cleared we had to crawl around in the daylight, or, wait to place the mines at night to avoid NVA fire.

We were often shot at by NVA recoilless rifles and mortars. We never understood why NVA snipers did not kill us one at a time. We expected they would start picking us off one by one any day, which made placing the mines even more stressful. We recorded many of the minefield layouts on cardboard C-ration case covers because we did not have minefield recording sheets. In many cases we paced off the distance between mines by moving on our hands and knees to avoid being shot at or mortared while standing.

We did all this with only one compass that we guarded carefully. When Lt. Gay was wounded he held tightly to that compass even while being treated at Charlie Med, until he could pass it on to Sgt. Sniegowski. If that compass was off, anyone entering the minefields with another compass was at risk. Over the years, we've had the chance to talk to Marine and Army troops that used our minefield recording sheets. We are proud to say that whenever the sheets could be found they were found to be accurate preventing US casualties. Sadly there were many situations where the recording sheets were not found and troops were wounded in our minefields.

We had lots of close calls in the minefields. Once, one our squads found themselves in a maze of grenade and trip wire booby traps the ARVN Rangers placed without telling anyone. While extracting themselves, they crawled through the human waste the Rangers routinely left in front of their positions. We decided that pushing Bouncing Betty mine detonation prongs through a piece of human waste was another good way to fool NVA Sappers, so we added it to our list of camouflage tricks from that day forward.

Many other close calls came as we armed hundreds, if not thousands of mines. We found many old ones from World War II and the Korean War to be in poor condition. We tried to "get the word out" every time we found a problem or a solution because we knew the grunts on the Hills were placing their own mines. Other terrifying close calls came when air dropped supplies would miss the drop zone and land in the minefields. Sometimes we only had to carry the supplies out of the minefields. Other times we would stand frozen in a partially finished minefield as parachutes with tons of palletized supplies came rushing out of the fog. It was a miracle that those pallets did not set off a mine near us or crush any of us.

Many NVA Sappers were surprised and killed by our booby traps as they tried to infiltrate at night, especially in front of the ARVN Rangers. The NVA would have taken heavy losses if our artillery and air power did not stop all of the full-scale attacks they tried to mount against the KSCB. It was gruesome and scary going back in to our minefields to get the NVA bodies out because they were mangled and we knew any mine near the one they set off was now super sensitized. But going in to get their bodies out became a regular task.

Taking the NVA Prisoner That Told Us About The NVA Battle Plans

Shortly before the NVA ground attacks started and after much work on the new fields of fire and protective fences was finished, an NVA recon patrol, including senior officers, risked taking a personal look at the new perimeter. They were discovered and killed trying to escape. As they retreated, one NVA Officer stayed behind and hid. After a few days, he surrendered to the Engineers as we placed mines on the perimeter. We turned him over to the grunts and kept working. His information caused Hill units to attack the NVA while the NVA was moving into position to attack the Hills. A good part of the NVA battle plan must have been changed by the Marines taking the initiative and attacking first.

Imagine what would have happened if the new perimeter had not concerned the NVA so much that they felt they had to try their daring reconnaissance patrol, enabling an NVA officer with so much knowledge of the coming attacks to defect and warn us? Also imagine what would have happened if the few ground attack probes the NVA did try against the KSCB were not so restricted by all the new fields of fire, fences, and minefields?

Opening the Runway on 21 January 1968

When the NVA artillery attacks started on 21 January 1968, the Engineers immediately went to work clearing shells blown out of the ammo dump onto the airstrip. It was a hectic morning filled with CS tear gas, confusion from enemy fire and secondary explosions. We know there were EOD personnel on the KSCB, but we can not remember working with them that day. There was just so much to do that everybody just did what was needed without formal coordination. We did our part to get the airstrip opened, to get casualties out and keep supplies coming in.

Building Bunkers

Before the Siege, many units at the KSCB lived in tents on wooden platforms surrounded by 55 gallon drums filled with dirt and topped with sandbags to create protective walls. After the first day of the Siege, everyone wanted to live completely underground in bunkers. Fortunately, we always lived in bunkers. Before the Siege, friends from other units joked about our damp, dark, cramped bunkers. After the Siege started, everyone envied us. Throughout the Siege, we built some bunkers but mostly, according to military doctrine, we trained people to build them themselves. That was a way to get everyone building.

The

Fire Direction Center (FDC) bunker we built for 1/13 was the biggest bunker we

built. It is an amusing story. None of us were trained to build large bunkers.

We were trained to blow up bunkers, tunnels, and bridges. After brainstorming we

ended up using the Seabee equipment to dig a large slit trench over which we

built a bridge strong enough to carry a tank. Then, we covered it.

The

Fire Direction Center (FDC) bunker we built for 1/13 was the biggest bunker we

built. It is an amusing story. None of us were trained to build large bunkers.

We were trained to blow up bunkers, tunnels, and bridges. After brainstorming we

ended up using the Seabee equipment to dig a large slit trench over which we

built a bridge strong enough to carry a tank. Then, we covered it.

We put empty artillery canisters upside down on the bunker to create a "burster layer." A burster layer detonates a round above an empty space, dissipating the explosion instead of focusing it on the bunker structure. In this case, the NVA rounds exploded when they hit the canister tops, dissipated the blast into the empty shell casings. We got the word out about this use of empty 105 canisters. Soon, almost everyone was making their bunkers stronger with "burster layers." That saved a lot of lives.

Our burster layer solution was real personal. One of our bunkers took a direct hit. Thanks to the burster layer only a support beam split. The bunker did not cave in — that could have killed or wounded many of us. We emerged shaken but alive and started building double and triple burster layers.

The Water Point Miracle

Our success in keeping the KSCB supplied with water was a miracle. We can't believe the NVA didn't target the KSCB water supply. They probably never thought that a reinforced Regiment would depend on a water source located outside of its perimeter and not under its control all the time. The water point was set up sometime in early 1967 outside the eventual KSCB perimeter. This was probably done when the Marines thought they would just be there temporarily.

We had to pump water up from a stream located in a gully on the north side of the perimeter. The NVA could have diverted or contaminated our water source since the stream flowed from terrain the NVA held. The pump had to be hauled down to the stream to pump water up to fill storage bladders.

We drew a lot of mortar fire doing that. They could have

ambushed us and destroyed the pump every time we rolled it down the hill to pump water up. To our amazement, even

though the NVA routinely hit us with recoilless rifle fire when we worked in the

minefields, they never ambushed us when we hauled the pump out. They never had a

sniper take us out, even though we had to haul the pump out once every few

days.

every time we rolled it down the hill to pump water up. To our amazement, even

though the NVA routinely hit us with recoilless rifle fire when we worked in the

minefields, they never ambushed us when we hauled the pump out. They never had a

sniper take us out, even though we had to haul the pump out once every few

days.

We may have survived because we hauled the pump at such great speed that we surprised everyone. One day we narrowly escaped a napalm drop by the Air Force near the pump site, because the FAC didn't know we were out there. The pipe from the pump up to the bladders was often punctured. During one especially long afternoon and night, we had to figure out how to create a whole new pipeline from damaged pieces. How we solved that unique problem is hilariously funny to explain now. It wasn't funny then. We were being mortared almost the whole time we were crawling around fixing the pipeline. The bladders and purification equipment were damaged daily. We could write a book about the innovative ways we repaired them. Before long, we were patching the patches.

An Engineer Lance Corporal (we think his name was Shipman) kept the water point operating. He is one of Khe Sanh's many unsung, unglamorous heroes. He was always working in wet torn clothes. He also always sported a few bandages from small shrapnel wounds for which he didn't feel he should receive a Purple Heart. Shipman is one of many that deserves an award but never got one. We all just thought we were just doing our job. If Shipman's name was Christman, he died with one of our other platoon members, PFC Emmett Stanton, when the chopper they were on was shot down on 28 February. Stanton and Christman are both listed as "unit unknown" on the KSV Memorial List. Being killed and unidentified was the lot that befell Engineers, since we were attached to larger units and not always accurately counted in the confusion of combat.

Most of us at Khe Sanh didn't even know Stanton was killed until years later. Until we hear otherwise, we will place Christman among our honored fallen, rather than leave him listed as "unit unknown." He had an MOS that was related to the 350 GPM fuel pump that was cleaned and used to pump water to the KSCB.

PFC Delano arrived to replace Christman to keep the water point going. He was soon killed by shrapnel. Who would have ever thought running a water point could be so dangerous? Imagine what Khe Sanh would have been like if we had to run patrols down to the stream to get cans of water instead of pumping it up at 350 gallons a minute, or worse yet, if we had to fly water in because the NVA diverted the stream or simply dumped a few of their decaying dead in the stream everyday?

Bunker Rats

Ray Stubbe in a recent article in Red Clay quoted World War II studies that found that as many as 90% of combatants exposed to continual combat for over 60 days suffer some form of battle fatigue. That wouldn't surprise us, especially when you add the effects of our horrendous living conditions to our constant exposure to danger. Our normal physical condition was one of continual stress from being exposed to danger and to the loss of our comrades, sleep deprivation, hunger bordering on malnutrition, and incredible body filth because we had only enough water to drink.

Our bunkers were alone at the northeast end of the airstrip, across the road from a 1/13 artillery battery. Being alone was good because we could keep our area clean thus controlling the never ending battle with the rats infesting all the bunkers on the KSCB.

Other units had to evacuate personnel because of rat bites. That never happened to us. The bad news about our bunker locations was the incessant artillery fire directly over us night and day. The out-going, added to the constant enemy incoming, made it hard for those of us not helping the grunts man the perimeter at night to get any sleep.

Our isolated position at the end of the airstrip also made it necessary for us to man guard positions around our own area. It would have been easy for an NVA Sapper to drop a satchel charge in our bunkers if one had ever penetrated the perimeter. Between the physically exhausting workload everyday and the perimeter or guard duty we had every night, we probably were much more severely sleep deprived than we ever imagined. Getting basic supplies was also a challenge. Engineers, like other support units at KSCB that operated in a quasi-orphan status without a parent organization often had to scrounge what we needed. Some of our exploits sound like they were written for MASH, the TV Show.

We would trade C4 plastic explosives, which could be burned to heat C-rations, for canned fruit and other goodies that we couldn't get as an independent platoon. Finding an onion was always a special treat that resulted in us all combining our C-rations in a large can to create a "hobo stew" which broke the monotonous taste of the C-rations. We would position a few daring souls to pop up as soon as NVA incoming stopped to go over the fences into the food storage areas and throw out a few cases of fruit or something else good to eat. Most of us lost ten pounds or more before we left Khe Sanh because we only received one, maybe two rations a day even though we worked hard. We suffered varying degrees of malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies. We were just young men, almost all of us under 21 and still growing. We were always hungry.

Our clothes or boots rotted off our bodies, or were torn to shreds in the barbed wire, so we posted an Engineer at Charlie Med to bring us clothing or more M-16 magazines thrown out by the corpsman after they evacuated the wounded and dead. Having to haul heavy loads of mines and other materials was always a problem. Due to constant exposure, it wasn't long before all of our equipment and our only truck were hit so many times by NVA shrapnel that they could not be repaired. This led to our biggest "heist" — a jeep and trailer. We jumped in and drove off with it after the occupants of the jeep jumped out to take cover during incoming. No one remembers the rightful owners ever reclaiming the jeep. We hope that occurred only because of the confusion at the KSCB and not because the original occupants were wounded and evacuated. Life was not easy for anyone at the KSCB. It was hard for us as an independent unit, but we had it many times better than the Marines on the Hills. We'll never forget them. We worked harder on the KSCB, because we knew we were indirectly helping the Hills.

Our Losses Increased