Hollywood

movies with all their inaccuracies were at least entertaining but

British Cinema, apart from a very few exceptions was pretty dull and

extremely formulaic.

For many years every single actor in England had an upper class

background.

Why this should be so reflects the class distinctions extant

between the wars and up to the 50's.

It was only after this time that working class actors and

actresses started to get parts in British films and prove to be far

more accomplished than their predecessors ever were.

Prior to this you would have some upper-class twit portraying a

toilet-attendant or some such and speaking in Oxford English with a

"h" missed out here and there and that was their idea of

working class.

Even worse than the accent was the fact that any "working

cove" was invariably deemed to be as thick as a brick and

patronised accordingly.

But the real

h owler was always the maid who was

invariably as daft

as a brush and never seemed to have any home life.

Not only that, because they

had never

set eyes on a two up or two- down or been in a semi the screenwriters

assumed that everyone in England had a maid

so you will invariably see feather dusters everywhere in English films

of this era.

And the very worst part of this scenario is that audiences

everywhere watched these mangled distortions of themselves without a

murmur. owler was always the maid who was

invariably as daft

as a brush and never seemed to have any home life.

Not only that, because they

had never

set eyes on a two up or two- down or been in a semi the screenwriters

assumed that everyone in England had a maid

so you will invariably see feather dusters everywhere in English films

of this era.

And the very worst part of this scenario is that audiences

everywhere watched these mangled distortions of themselves without a

murmur.

Another

constant which

runs through these black and whites is the

"boyfriend" of the heroine who is invariably in his forties

or even fifties, sports a flip-brim trilby and is overweight.

His redeeming qualities, if they can be said to be such, are

his upper-class background and his pots of money.

This doesn't say much for the heroine who is usually 30 years

younger than her boyfriend.

Impoverished and from a working class family who speak Oxford

English she plays tennis to keep her spirits up while avoiding the

constant attentions of her creepy beau and is of course as chaste as

the driven snow.

The

classic examples of all of this run through every George Formby film

he ever made and without ever knowing it George opened a window into

just how class ridden England was at that time.

No matter what the setting, the formula was always the same ---

the girl always sees through her boyfriend's evil intent in the nick

of time, returns to her working-class roots in the form of a bumbling

but loveable George and looks toward a golden future of tennis and

chips for the next 40 years.

The

main theme of all these films is of course George's clowning and most

audiences were content to see it on those terms but it is

revelatory at how they accepted the class distinctions as the norm.

Certainly

everyone has their own opinion about what they like and what is good

and what is bad and quite often "good" can be dull whi le

"bad" can be extremely entertaining.

As an example, one of the most stultifyingly boring films ever

made is still

doing the rounds today and generally accepted as a

classic of the British cinema. There

are even people who travel to Carnforth

railway

station where the film was shot and taking geekdom to its ultimate one

or two of them actually re-enact scenes from the film with themselves

as players. Just

how a film mainly set in a drab and depressing railway cafe where they

sold drab and depressing tea and buns and outside was a drab and

depressing rain could ever inspire the dog-like devotion this film

inspires is completely beyond me.

The film is of course Brief Encounter

{ 1945 }

and again brings into focus class distinctions common

at that time.

How the middle- class- but- married doctor Trevor Howard could

fancy the middle- class -but- married Celia Johnson of the

bulging eyes and Olive Oyl figure is beyond me but fancy her he did and audiences

queued for miles for a slice of this suburban angst. Even if she

had been a reincarnation of every femme fatale who ever made a movie

her strangulation of the English language grates like glass on a

blackboard and

I

strongly suspect that most of the ladies who went to see this film did

so to gaze upon the courteous and refined Trevor Howard feeling an

affection for him

something

akin to the way they felt about the family doctor. The

only redeeming feature of this picture that I can see is that the

trains ran on time which is a heartwarming slice of yesteryear but

hardly worth the entrance fee. le

"bad" can be extremely entertaining.

As an example, one of the most stultifyingly boring films ever

made is still

doing the rounds today and generally accepted as a

classic of the British cinema. There

are even people who travel to Carnforth

railway

station where the film was shot and taking geekdom to its ultimate one

or two of them actually re-enact scenes from the film with themselves

as players. Just

how a film mainly set in a drab and depressing railway cafe where they

sold drab and depressing tea and buns and outside was a drab and

depressing rain could ever inspire the dog-like devotion this film

inspires is completely beyond me.

The film is of course Brief Encounter

{ 1945 }

and again brings into focus class distinctions common

at that time.

How the middle- class- but- married doctor Trevor Howard could

fancy the middle- class -but- married Celia Johnson of the

bulging eyes and Olive Oyl figure is beyond me but fancy her he did and audiences

queued for miles for a slice of this suburban angst. Even if she

had been a reincarnation of every femme fatale who ever made a movie

her strangulation of the English language grates like glass on a

blackboard and

I

strongly suspect that most of the ladies who went to see this film did

so to gaze upon the courteous and refined Trevor Howard feeling an

affection for him

something

akin to the way they felt about the family doctor. The

only redeeming feature of this picture that I can see is that the

trains ran on time which is a heartwarming slice of yesteryear but

hardly worth the entrance fee.

The Director David Lean went on to better things as did

Trevor Howard. He was the

complete antithesis of all that his doctor in Brief Encounter

engendered when he played Lord Cardigan in The Charge of The Light

Brigade -irascible, garrulous and lascivious as he led his 600

cavalrymen into the Russian cannon.

Actually, this film portrays the Crimean War in a very

realistic manner, keeping strictly to historical fact and exploring

the dynamics of each relationship faithfully.

Again, class distinctions are very much a part of the film but

in this instance

they are portrayed just as they were in Victorian times with the lines

drawn distinctly and rigidly and the lower classes accepting their lot

placidly as if it had been pre-ordained from on high.

Norman Rossington's portrayal of a dishevelled and weary

cavalryman after the carnage of the Charge has him saying to his

superior " Go again Sir ? " which emphatically illustrates

the relationship between officer and soldier ---a relationship which

carried over into civilian life.

Apart

from George Formby and Gracie Fields providing some light relief most

of the black and white films in the 30’s and 40’s were serious

stuff. In fact many British films of that era have the strange quality

of being an extension of school lessons as if movies had to justify

their very existence by being educational.

There seemed to be a sense of self-conscious belief that if a

film deviated from some serious theme approved by the establishment

then it was accordingly frivolous and therefore degenerate.

Nobody seemed to notice that it flew in the face of Ars Gratia

Artis or if they did then they didn’t care. Apart

from George Formby and Gracie Fields providing some light relief most

of the black and white films in the 30’s and 40’s were serious

stuff. In fact many British films of that era have the strange quality

of being an extension of school lessons as if movies had to justify

their very existence by being educational.

There seemed to be a sense of self-conscious belief that if a

film deviated from some serious theme approved by the establishment

then it was accordingly frivolous and therefore degenerate.

Nobody seemed to notice that it flew in the face of Ars Gratia

Artis or if they did then they didn’t care.

Goodbye

Mr Chips

{ 1939 } was an

unashamedly sentimental homage to our English way of life epitomised

by the Public School system. Robert

Donat and Greer Garson were outstanding in a film rightly acclaimed as

a classic of the genre. An

unfortunate consequence of Chips was that it was so successful that it

spawned endless numbers of copycat scripts, some good but most very

poor and for a long time it was a case of “Chips with everything”.

Even

as late as 1948 the Boulting Brothers were squeezing the last pips

from the subject with a film

called The Guinea

Pig. The

film began reasonably enough, leaning slightly to the view that class

barriers were coming down and a working class lad at a Public School

was a social experiment worth following.

From that point onward the whole thing degenerated into a

homily on the virtues of cut-glass accents and stiff upper lips and

capital punishment and ended up as an embarrassing Pythonesque re-mix

of “Chips.” Sad to say, Richard Attenborough as the Guinea Pig,

bursting out of his school uniform, sold out to the establishment. One thing that stands out is just how difficult it was at

that time for anyone without a Public School grounding to get to

University no matter how high their ability.

So,

if you weren’t into slapstick and a return to school days did not

appeal then Hitchcock’s adaptation of John Buchan’s

The 39

Steps

{ 1935 } was

perhaps 39 steps more in the right direction.

Robert Donat playing the innocent engineer caught up in a web

of intrigue has charisma and charm in abundance.

Combined with a picaresque and action - packed plot the film

plays well even today. Kenneth

Moore did it again in the 50’s just as successfully and you could

argue forever which is the better version.

One scene in the Kenneth Moore film is hilarious, when on the

run he stumbles through an impromptu speech at a girls school and this

scene alone shades it for me.

Great

Expectations

made in 1946 by David Lean was an excellent adaptation of the Dickens

story with John Mills as Pip

and Jean Simmons as Estella while Moira Shearer did the impossible

managing to make ballet popular with The Red

Shoes.

Not to be outdone, Dirk Bogarde attempted “ a far, far, better thing”

as the degenerate Sydney Carton who famously sacrifices himself in a

final act of redemption on the guillotine in Dicken's A

Tale of Two Cities.

Noel Coward chipped

in

with a patriotic war-time propaganda effort

In Which

We Serve

{ 1942 }

with John Mills to the fore as a chippy cockney sailor and all in all,

cinema audiences of that era must have been the best educated and

patriotic, not to say brain-washed in the whole of the western

world. They were even happy to be shown to their seats.

The

concluding impression I had then and still do, is that for a country

rich in history and event, the British film industry was and is

remarkably insular in choosing both subject and content for its

movies.

It

is fair to say that the films of the 50’s and 60’s echoed the

changing times. Nevertheless,

although grittier and wider in content there was still an overriding

penchant to “give out a message” or explore in depth

some

social scenario -it

seems that they just couldn’t bring themselves to have fun.

The

Bridge on The River Kwai by

David Lean, combined William Holden and Alec Guinness and Jack Hawkins

in an exploration of the effects of life in a Japanese prison camp.

Made in 1957, the film was uncomfortably close to reality and

too soon after the war for many people but it was an excellent study

of a British officer under pressure in an intolerable situation.

Yet another study of an officer under pressure was Tunes

of Glory

{ 1960 }, an

excellent psychological drama where Alec Guinness was never better as the odious

and thick-headed Lt. Colonel Jock Sinclair in charge of a Scottish Regiment.

John Mills plays the new commanding officer, Colonel

Barrow, who Sinclair

resents and despises for his upper-class upbringing.

Sinclair is too stupid to foresee any consequences to his

constant undermining of Colonel Barrow’s position and the situation

leads to tragedy for both men.

Great little movie with two great actors honing their skills in

readiness for greater things.

Another great little movie of this era was the superb adaptation of

Melville's novel, Billy

Budd.

Terence

Stamp excelled as the stammering, young seaman whose life was made a misery by Robert Ryan's Master-at- arms during the Napoleonic Wars.

Nearer

to home, a slimline Albert Finney, a delicious Shirley Anne Field and

a hard-edged Rachel Roberts played out one of the forerunners of

the "angry young man" crop of films in Saturday Night

and Sunday Morning. Albert Finney struck a chord with his

portrayal of a factory-hand striking out at everything and everyone in a blind rage at a life he

was supposed to be happy wit h. After

all, he had everything he could want –a steady job, the obligatory

binge in the pub at the

weekend and a nice girl friend. The

vague rage inside that there could be so much more and that it was

perhaps a life unlived was later echoed by James Dean in Rebel Without

a Cause. Rachel Roberts

is Finney's female counterpart and they both find solace in an illicit

sexual liaison which finds her eventually pregnant with a husband to

face.

Her performance is a tour-de-force suggesting a real life intimacy

with the subject matter. h. After

all, he had everything he could want –a steady job, the obligatory

binge in the pub at the

weekend and a nice girl friend. The

vague rage inside that there could be so much more and that it was

perhaps a life unlived was later echoed by James Dean in Rebel Without

a Cause. Rachel Roberts

is Finney's female counterpart and they both find solace in an illicit

sexual liaison which finds her eventually pregnant with a husband to

face.

Her performance is a tour-de-force suggesting a real life intimacy

with the subject matter.

Room

at The Top has Laurence Harvey as an angry young man with a precise

knowledge of his problems and a willingness to do something about it.

The problems arise when ambition turns into ruthlessness and

from then on it all starts going wrong.

Mind you, he gets to have an affair along the way with every

schoolboy's dream girl Simone Signoret which is not a thing to be

treated lightly.

The

educational ethos was still present in films such as

Far from The

Madding

Crowd

but with players such as Peter Finch, Terence

Stamp and Julie Christie nobody was complaining and even heavy dramas

such as D.H.Lawrence's

Women in Love was

acceptable mainly due to the presence of Glenda Jackson and Oliver

Reed.

And

just to reinforce the

changes that were taking place there was actually a British musical !

------ Oliver

made

by Carol Reed in 1968. The

inspired casting went a long way to making the movie into a class act

with Ron Moody superb as Fagin, Jack Wild the epitome of an Artful

Dodger, Shani Wallis as an appealingly pathetic tart - with -a -heart

and best of all Oliver Reed was evil incarnate dripping malevolence in

his wake accompanied by the no less malevolent Bullseye, his dog.

It had been a long time coming but this was great stuff from

the British cinema. At

long last the stars had roles they could get their teeth into and

“entertainment” had for once taken precedence over angst.

The

chequered history of British film continued and whenever David Lean

made a film it inevitably stood out from the rest.

After

Dr

Zhivago and

Lawrence

of Arabia I

was beginning to warm to David Lean after his aberrations with Celi a

Johnson a

Johnson

and when

Ryan’s

Daughter

came along total redemption followed. Robert Bolt wrote the story, loosely based on and inspired by

Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, and David Lean turned it into

a magnificent film. Set

in the West of Ireland in 1916, the infamous Black and Tans are led by

a Major Doryean { Chris Jones } suffering from shell-shock which

manifests itself whenever Doryean is under stress.

Sarah Miles in possibly her best-ever role as Rosie Ryan falls

for the young Major and they have an illicit affair.

Illicit because Rosie is betrothed to Shaughnessy, the staid

and passionless schoolteacher played by Robert Mitchum who for once

gives some inkling of the actor that he could have been At first the role fits perfectly with Mitchum’s wooden

acting persona but he comes into his own later in the film when

Rosie’s infidelity comes to light and Mitchum reveals depths

previously rarely shown in his sympathy for her plight. Trevor

Howard is excellent trying to keep his recalcitrant flock in order but

John Mills stole in behind everybody and claimed the Oscar for his

portrayal of Michael, the village idiot.

If this film had been made today, there would have been naked

bodies writhing everywhere because “the audience demands it” I don’t think

the audience does demand it and neither did David Lean when he said ;

“To

suggest sex and leave it to the audience is much more erotic than

showing it all.

Sex

is imagination".

This

was great stuff and a breathless audience awaited more but Lean

chose to wait 16 years before making another film.

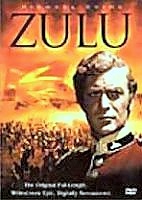

Things

became even better in 1964 when mine and many other people’s

favourite British film of all time burst onto the screen with

unprecedented impact. The Director was Cy Endfield and the film was Zulu.

The subject matter was the siege at Rorke’s Drift in 1879

when a 3,000 strong force of bloodthirsty Zulu warriors fresh from the

massacre at Isandhlawana were looking for fresh conquests.

The few hundred soldiers at the isolated settlement decided to

remain and fight a holding action rather than be caught out in the

open and the film concentrates on the ebb and flow of the battle in a

fascinating and realistic enactment of the action.

Michael Caine’s interpretation of a typical British officer

of the era is on the face of it a scathing representation of a

foppish, self-serving and class-ridden individual but as the film

unfolds his Gonville Bromhead’s anachronistic eccentricities and

depth of character become endearing.

This is quite an achievement particularly for such a young

actor because it would have been far easier to have stayed with a

one-dimensional cardboard

cut-out interpretation of the character.

Stanley Baker, playing the pragmatic

Lt. John Chard was the perfect foil for Caine while James Booth

was perfect as the cockney Henry Hook.

Richard Burton’s narration was similar to his voice-over on

War of the Worlds when his laconic and liquid tones carried far more

gravitas than some of the more hysterical narrations I have heard [

mostly American }. Things

became even better in 1964 when mine and many other people’s

favourite British film of all time burst onto the screen with

unprecedented impact. The Director was Cy Endfield and the film was Zulu.

The subject matter was the siege at Rorke’s Drift in 1879

when a 3,000 strong force of bloodthirsty Zulu warriors fresh from the

massacre at Isandhlawana were looking for fresh conquests.

The few hundred soldiers at the isolated settlement decided to

remain and fight a holding action rather than be caught out in the

open and the film concentrates on the ebb and flow of the battle in a

fascinating and realistic enactment of the action.

Michael Caine’s interpretation of a typical British officer

of the era is on the face of it a scathing representation of a

foppish, self-serving and class-ridden individual but as the film

unfolds his Gonville Bromhead’s anachronistic eccentricities and

depth of character become endearing.

This is quite an achievement particularly for such a young

actor because it would have been far easier to have stayed with a

one-dimensional cardboard

cut-out interpretation of the character.

Stanley Baker, playing the pragmatic

Lt. John Chard was the perfect foil for Caine while James Booth

was perfect as the cockney Henry Hook.

Richard Burton’s narration was similar to his voice-over on

War of the Worlds when his laconic and liquid tones carried far more

gravitas than some of the more hysterical narrations I have heard [

mostly American }.

The

battle scenes are second to none with the fight in the hospital where

Hook won his V.C. the most exciting of all.

But just as nerve-wracking are the intervals between the action

when the ever diminishing force regroup time after time.

The Zulu warriors as individuals are truly scary but when the

waves of Zulu regiments appear filing over the veldt walking

increasingly faster until they break into a run and finally racing

forward with the battle cry Usuthu! the effect is electric.

Many

scenes are memorable but the one that stirs the blood is when the

formidable army of Zulus stand on the hillock ready to attack and

banging on their shields in unison chant Usuthu over and over again.

The fear in the ranks of the soldiers is palpable until the

largely Welsh regiment respond with a stirring rendition of Men of

Harlech.

I have seen this film many times and it stands as one of the most

exciting films of all time. Rorke’s

Drift has become legendary and whenever we watch such re-enactments of

historical events there is no doubt that each and every one of us

imagines ourselves on the field

of battle and always in some heroic role.

Zulu

was a difficult act to follow and sadly it was a one-off.

There are no British films after this that I can think of which

hold a candle to it. Cy

Endfield had set the standard and thrown down the gauntlet and nobody

has to date picked it up.

It has been said that the British press made much of this

battle in order to minimise the catastrophe which had taken place at

Isandhlwana a few hours earlier. Critics of the film are in a

minority but some have pointed out that the depictions of Hook, Chard

and Bromhead are incorrect. Whether this is true or not Zulu

remains the most exciting and authentic version of the battle that we

are ever likely to see. Cy Endfield received all the praise but Zulu owes a great deal to John Prebble's screenplay. Historian and author, Prebble has the knack of bringing history alive.

It’s

not true to say that things went downhill after that because many good

films have been and still are being made but British films always seem

to revert to the formulaic, family angst films to the exclusion of

adventure films when a healthy dose of each would be acceptable.

Michael Caine was naturally snapped up Hollywood but returned as the

drunken professor in the excellent Educating Rita

from the play by Willy

Russell. Originally set

in Russell’s home town of Liverpool, the film was shot in Dublin

because it was alleged to look more like Liverpool which has always

been a puzzle to me. Nevertheless,

Caine was brilliant in his role of a world-weary professor of English

Literature as was Julie Walters as Rita.

One of the main reasons we enjoy certain films is that we

identify with such and such a character and while a young girl would

never see herself behind the mealy-bags in Rorke's Drift there is many

a one who could identify with Rita. The number of people I have

met over the years who are not well-read or have a formal education but

are clever and quick in their own right is truly astounding and there is

surely a male variant of the Rita story waiting to be made.

Another

very similar film was Shirley Valentine

again by Liverpudlian

playwright Willy Russell which combined the classic combination of

humour and pathos to make an excellent “ I’m gonna do that just

as soon as I

leave the cinema" film.

A blow for freedom for bored housewives

everywhere, many identified with the heroine played by Pauline

Collins. The wry Scouse humour combined with the feisty housewife who escapes to

Mykonos and meets up with a handsome Greek

{ Tom Conti } struck a chord and this film has become a cult classic

in certain quarters -- one of them is our house.

There

are of course always the Bond films which started out quite well with

adaptations of Ian Flemings novels such as From Russia with Love

working very well but sadly the storylines have been superceded by the

so called special-effects and the whole thing has turned into a

caricature of what Fleming intended.

The

Day of The Jackal [1973 } was a

good example of which way we should be going with Edward Fox perfect

as the chilling assassin - in

fact Fox's assassin was far more in keeping with Fleming's

conception of Bond.

In many ways Producers often shoot themselves in the foot by making

films which they think the public want but in many cases the aficionado

of any given hero such as Bond want nothing more than a true

representation of how they see the character. Anyone who produced

a Bond with the quality of Jackal and the menace of Edward Fox would be

doing more of a service to the public and produce consistent quality

rather than the cartoon-like films that Bond has descended to.

But

for every film such as this there are too many lightweight things like

Notting Hill

which are simply vehicles for Hugh Grant to

pretend he is as good as Cary Grant.

The execrable

51st

State quite recently

plumbed the depths with Robert Carlyle’s Scouse accent deplorable

and a script written presumably while waiting for a bus.

Like so many before, the film exploited the stereotyped image of the

Liverpudlian as a loveable scally, threw in a Hollywood star, Samuel.

L. Jackson in a kilt and set up one or two so-called action scenes and

hoped there were enough geeks out there to make it pay. We and

they can all do so much better than that but it seems that

for every step forward there must be two steps back.

But

every now and then British cinema throws up a gem and they don't come

much better than the little known

East is East {

1999 }

Directed by

Damien O'Donnell

Set in Salford in the 1960's to a background of Enoch Powers

"Rivers of Blood" speeches, the film follows the misadventures

of an Anglo-Pakistani family with a white mother { Ella Khan } played

superbly by Linda Bassett and her traditionalist Pakistani husband { George Khan }

played brilliantly by Om Puri.

Set in Salford in the 1960's to a background of Enoch Powers

"Rivers of Blood" speeches, the film follows the misadventures

of an Anglo-Pakistani family with a white mother { Ella Khan } played

superbly by Linda Bassett and her traditionalist Pakistani husband { George Khan }

played brilliantly by Om Puri.

Advertisements of Enoch Powell speeches are a total irrelevance as the

whole family, like so many others, are too absorbed in attempting to

make something of their lives to have the time to take an interest in

the larger picture.

The central theme is George Khan's crusade to preserve Muslim values

within his family while living within a Northern English cultural

background. The opening scene where the Anglo-Pakistani children are

carrying the banners at the head of a Catholic parade while their father

returns from the Mosque sets the scene to perfection.

Most of the seven children whose ages range from early twenties down to

12 year old Sajid accept George's dictates when he's around but ignore

them when he's absent ----cooking bacon sandwiches, sneaking off to the

disco, tomboy Meenah playing football in the streets and so on. Ella and

the children have become as English as fish'n chips while George after

30 years in England is still attempting to live life as a Muslim father.

George's minor dictates are either flouted or carried out with a

grudging acceptance for the most part but when he moves into the world

of arranged marriages it is a step too far and the effect is cataclysmic

upon the whole family. Nazir jilts his arranged bride at the altar and

is disowned by his father who nevertheless presses on and arranges a

joint marriage for two of his other sons.

The film is essentially a comedy and is hilariously funny but like all

good comedy it has a poignant counterpoint underscored by one scene in

particular when George gives Ella a hiding. This scene is extremely

brutal but totally in keeping with George's vision of how a Muslim

father should act in order to retain order within his family.

Linda Bassett's Ella deserves a special mention as she carries on

working in the chip shop and soldiers on in order to keep body and soul

together while George plays the Muslim patriarch. Ella is identifiable

with legions of Northern working class women who do the same thing in

many different circumstances ----women work, men play.

The whole cast are superb and like it's writer and director they appear

to have had first hand knowledge of their subject.

As a comedy the film is unreservedly successful but it examines and

dissects racism, hypocrisy, integration, immigration and humanity in a

very perceptive and potent manner. The comedic overlay is not there to

soften the impact but only serves to emphasise that this film is a

serious study of Northern working-class life in the 1960's which is

possibly more relevant today than it was then.

Typically, the film is little known and was poorly advertised and the

poster appears to have been thrown together as an afterthought.

The film has a cult following simply because it has only become known by

word of mouth.

Overall,

while things are far from perfect on the British cinema front

they are still a far cry from Public school propaganda movies but

nevertheless our actors and actresses continue to defect as they have

always done. The reasons

why they invariably head for Hollywood are financial of course but

there is no doubt that there is a greater choice of script usually

tailored to meet any given actors particular attributes.

From the days of David Niven our finest stars have headed west

and who can blame them when they end up in fine movies which showcase

their skills and lead on to even better things. Overall,

while things are far from perfect on the British cinema front

they are still a far cry from Public school propaganda movies but

nevertheless our actors and actresses continue to defect as they have

always done. The reasons

why they invariably head for Hollywood are financial of course but

there is no doubt that there is a greater choice of script usually

tailored to meet any given actors particular attributes.

From the days of David Niven our finest stars have headed west

and who can blame them when they end up in fine movies which showcase

their skills and lead on to even better things.

Daniel

Day Lewis, Anthony Hopkins, Sean Connery, Robert Shaw, Richard Harris,

Madeleine Stowe, Oliver Reed, Jude Law and so many more are all actors

and actresses who have that indefinable charisma which can convey so

much with a twitch of an eyebrow or a tilt of the head and they are

all making films which are both meaningful and entertaining.

Those two words should be engraved over what remains of the

British film studios and perhaps one fine day the tide will turn.

But the world is ever-changing and it is more and more difficult to

define what is a "British" film when British actors are

commonly seen in Hollywood movies, American stars play essentially

British roles and British technicians are common to American

films. Unlike continental films which retain their unique status

simply by reason of language and are instantly recognisable as French

cinema or Polish cinema or Spanish cinema and so on, British film has

like so much else of our culture for better or for worse melded with

American filming and in the process lost its identity completely.

|