| Chapter 1 |

| A Brief Overview of Copyright Law |

| For almost everyone, copyright law is a little fuzzy. This chapter is designed to give background information for the rest of our discussion. We�ll highlight some of the basic rights copyright laws provide and how they apply. |

|

| Image Provided by Andrew Flusche and by PugnoM |

| Part I: The Means and Ends of Copyright Law |

| First, why do we have copyright? At first glance, it seems we have copyright laws so authors can profit from their creations. Some even feel an author should have control over her work simply because she created it � a kind of moral right. On one hand, this may feel right. Why shouldn�t we reward someone who expends time, talents, and energy to create something we all enjoy? |

| Nevertheless, United States copyright law is founded on a different basis. Our Constitution authorizes copyright law in order to �promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts. . . .� The justification of having copyright law is not moral rights or economic incentives, but the advancement of knowledge. As a historical side note, the framers of the Constitution relied heavily on the Statute of Ann, an English law from 1710. This remarkable law departed significantly from prior English copyright laws which were used to control controversial ideas from ever reaching the public. The Statute of Ann, in contrast, was enacted to educate the public and encourage learning. The first U.S. copyright statute, enacted in 1790, followed the Statute of Ann and stated that it was �An Act for the encouragement of learning. . . .� So learning and public knowledge are the primary purposes of copyright law. |

| To emphasize the fundamental goal of copyright law, I omitted the second half of the Constitutional phrase and also the latter half of the original copyright act. I did so to clearly separate the means from the end. Public learning is the end, and now we will discuss the means to that end. The Constitutional clause continues �. . . by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.� The general notion is to provide an economic incentive for authors to create useful works. |

| To illustrate, imagine Annie Author, a brilliant writer who has the idea of authoring a series of moving novels. In order to write the first book, Annie puts in three months of time, effort, and energy. Finally, she finishes her work and sells the novel for $3 a copy. Now, absent copyright protection, another person could come along, photocopy Annie's work, and sell it for $2.50. Nobody would buy a book for $3 when you can get an identical copy for $2.50. In the end, Annie would make very little money for her efforts - and she probably won't write any more novels. And the public, that is you and I, would be worse off. Just think how sad it would be if J.K Rowling stopped after the first Harry Potter! |

| Copyright law uses �exclusive rights� (more on that in part III) as the means to encourage useful creation. But we must remember that the overall purpose is to advance public learning and knowledge. Keeping this in mind will make the rest of the copyright laws easier to understand. |

| Part II: What is Copyrightable and for How Long Does Copyright Last? |

| We live in a world surrounded by copyrighted material. Everything from pictures and paintings to blogs and buildings can be copyrighted. Copyright law requires an "original work of authorship fixed in a tangible medium" before copyright protection will apply. "Original" means you created it. "Work of authorship" means your work has to have some spark of creativity and internal coherence. This is not a high bar to cross, but it means things like an alphabetical listing of names in a phone book don't count. Anything more than an ordinary listing, process, or method will usually fulfill this requirement - but there must be some creativity. The law also requires that your work be "fixed in a tangible medium." To be eligible for copyright protection, a work must be written on paper, saved on a computer disc or CD, painted on a wall, or otherwise embodied in some physical object. This is so your work can be "perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration." In other words, you must have your work in such a form that others can use it. This may seem like a strange requirement at first, but remember the purpose of copyright law is public learning. When a work is fixed in a tangible medium, it can be disseminated and used by the public. No matter how great a creative work is, if it remains inside the author's head it doesn't really advance public learning. |

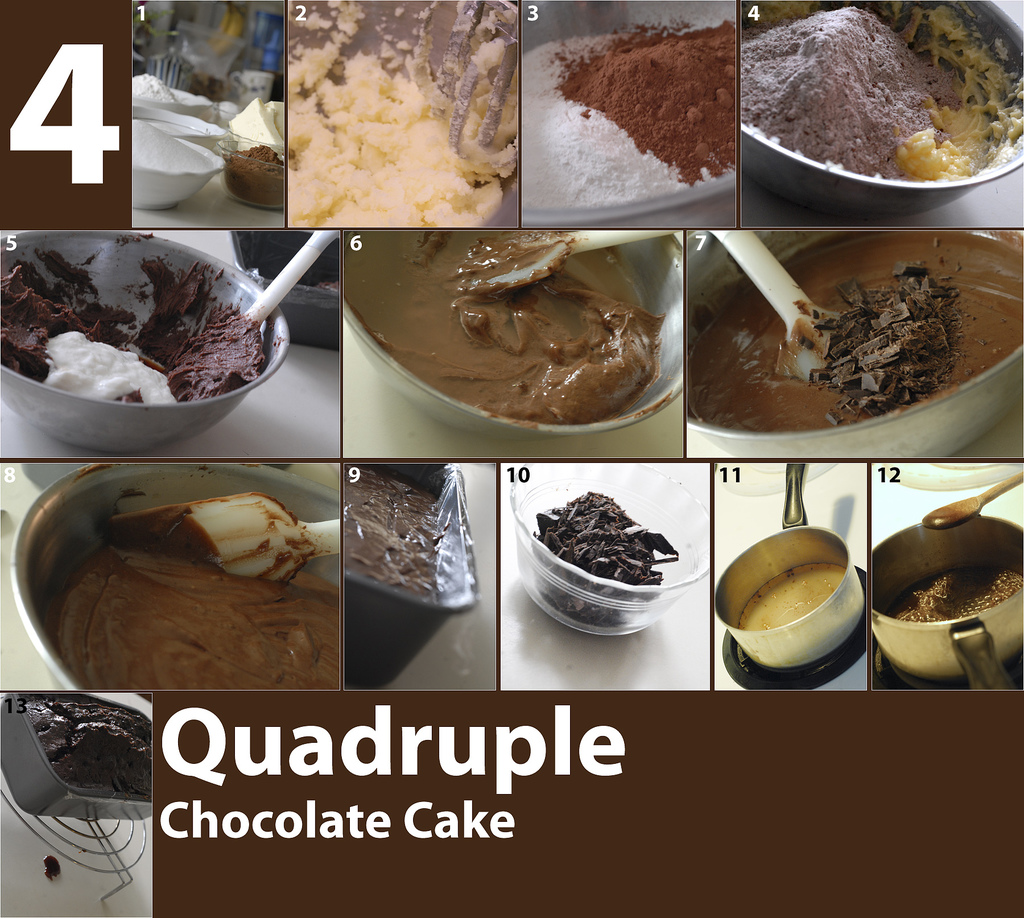

| The line between what is copyrightable, and what is not, may be hard to see at first glance. As an interesting illustration, imagine you have a cook book which contains the recipe for the most delicious chocolate cake in the world. A recipe describes a process, and thus is not copyrightable. However, the creative elements embodied in a page from a cook book, showing the recipe surrounded by drawings and images of chocolate cake, can be protected. But the list of ingredients (i.e. 2 cups flour) is not. Copyright law allows you to use the recipe or display it on your blog, but does not allow you to photocopy the page without permission. |

| Turning back to uncopyrightable ideas, suppose Annie Author�s first novel is a story about two young lovers whose families, blinded by religious bigotry, disapprove of their relationship. The basic idea of the novel, as I�ve just stated it, won�t be protected by copyright because it is simply an idea. However, the actual words and dialect of the novel, in other words the expression of the idea, is protected by copyright law. You can use Annie Author�s idea to write your own love story, but you cannot copy the words in her book when authoring your own without Annie's consent. If there are very few ways to express an idea, the doctrine of merger comes into play. Basically, ideas are unprotectable because they are needed to further public learning. Ideas are so important that if there are only a few ways to express the idea then copyright law will not protect that expression. The idea and expression have merged into an uncopyrightable creation. |

| The line between what is and isn't protectable can be hard to find. The general principle is copyright law does not protect ideas, processes, facts, etc., but only covers an author�s creative expression of the ideas, processes, facts, etc. When evaluating your work, how was it created? On one hand, did you use artistic judgment in creating the work? Are there multiple ways of expressing your work? On the other hand, does your work convey factual information? Is the form of your work driven by functional considerations? Affirmative answers to the first set of questions leans towards protection while the second set indicates no copyright protection. Some works may be an odd combination of ideas and some creative expression. In such a case, like the example of a page from a recipe book, you will have elements of the work which are protected and elements which are not. |

| The copyright office has indicated that "names, titles, and short phrases or expressions are not subject to copyright protection. Even if a name, title, or short phrase is novel or distinctive or if it lends itself to a play on words, it cannot be protected by copyright." The copyright office has a useful page which gives more information about what qualifies as a name, title, or short phrase. |

| Next, how long does copyright last? As noted in the constitution, a copyright is supposed to be for �limited Times.� Once a copyright has expired, the work will enter the public domain � which means anyone can use it however they want. In most cases a copyright will last until 70 years after the death of the author. That can be a long time, especially if the author is young and relatively healthy. The time frame may be slightly different if a work is created as part of employment, but it is still a long time. If you are dealing with an older work, for example something created before 1978, the copyright term may be different as well. If that's the case, look over Peter B. Hirtle's chart for a quick reference guide. |

| Part III: What Can Copyright Do For Me? |

| Current copyright laws grant six �exclusive rights� to a copyrighted work. An exclusive right means that the owners, and the owners alone, are legally entitled to exercise or authorize that right. Copyrights give owners the exclusive right to (1) make copies, (2) make derivative works, (3) publicly distribute the work, (4) publicly perform the work, (5) publicly display the work, and (6) publicly perform a sound recording by means of a digital audio transmission. This shopping list of rights is probably confusing � it certainly was to me the first time I saw it! But remember these six rights are supposed to cover every kind of copyrighted work, including books, music compositions, movie scripts, or even mp3 files. As we talk about specific examples, how these rights work will become more clear. |

| Before going into more detail, I must stop to note that there are important exceptions to these rights. These apply in situations where the exclusive rights will not further the advance of public knowledge. For example, libraries have a special exception to make archival copies. In the next chapter I will talk about one very important exception, Fair Use. |

| The first exclusive right is fairly straight forward: only the copyright owner can make or authorize copies of the work. A derivative work is a work based on one or more preexisting works. For example, the movie �Jurassic Park� is a derivative work based on the preexisting novel by Michael Crichton. The public distribution right includes distribution by sale (or other transfer of ownership), lending, lease, or rent. |

| The public performance right deals with works such as books, plays, or movies. It gives the copyright holder the exclusive right to play, dance, or show the work to the public. The public display right is similar in that it provides the exclusive right to display works such as paintings and sculptures in a place open to the public. The last right deals with digital sound recordings (like a CD or an mp3 file) and provides the exclusive right to perform the work publicly using digital technology. |

| To those unfamiliar with copyright laws (i.e. most of us), the exact limits of these rights may seem vague. For example, several of the rights are limited to �public� performances or displays. The rights do not prohibit you from privately displaying or performing a copyrighted work. In other words, it is ok to get a group of friends together and form a 6 a.m. exercise class using exercise videos and DVDs. Congress specifically defined "public" in this context to apply only in two situations. The first is when the event is open the public and everyone is invited. For example, movie theaters are open to the public because anyone can buy a ticket. The second is when an unusually large group is present. If the movie theater sends out a plethora of tickets to individuals, rather than selling them to the public, the performance of the movie can still be "public." How large is too large? Copyright law says the limit is "a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances." A rough estimate of this group is a wedding party. If you are performing your work to a party substantially larger than an average wedding party, then you may be infringing the public performance right. If the group is smaller, then you are probably ok. |

|

| Editor's Note: This image was provided by Homer Township Public Library. The author pictured is not really named Annie, but Heidi Bee Roemer. |

|

| As a side note, I found this image particularly amusing. While copyright laws don't explicitly allow God to copyright the design of human individuals, the image brings a unique perspective to copyright law's requirement of "original work of authorship fixed in a tangible medium." |

|

| Image (and recipe) provided by Smaku |

|

| Jurrasic Park - the Ride! Another example of a derivative work. Image provided by Flipsy. Looking good Flipsy! |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. |

| "You Are Unique, � GOD" Image provided by Squacco. |

| At the same time, there are many innovative creations which are specifically excluded from protection by copyright law. For example, copyright does not protect ideas. Facts, processes, concepts, principles, and discoveries are also not covered by copyright. Congress carved out these limits so that copyright law serves its purpose in advancing public learning. Scientific facts, for example, need to be freely available so others can build on existing knowledge. |

| Another exception, the First Sale Doctrine, allows you to resell or distribute copyrighted goods you have purchased without the copyright owner's permission. I highly recomment reading K. Matthew Dames� article on the first sale doctrine (as a side note, the website has a number of excellent articles on copyright law). He does a really good job of explaining in simple terms what first sale allows you to do. I would only add that there are additional complexities that arise with digital copies. For example, you can transfer �that copy.� But if the copy is stored on your hard drive, how do you transfer �that� copy? Computers create and send copies of files, and not the files themselves. Here is another example of where copyright law needs to be updated to keep pace with changing technology. |

| There are many specific limits and exceptions to the exclusive right. But for now just note that there are limits to these rights and that they might not apply in every situation. |