Matthew "came

into this world prematurely and he left prematurely," a press release from his

parents, Dennis and Judy Shepard, reads. An earlier statement said that his

"life has often been a struggle in one way or another," including many childhood

ailments. "We know that he thinks if he can make one person's life better in

this world, then he has succeeded. That is a measure of success Matthew has

always pursued."

The mythologizing of Matthew-his overnight

transformation into a national and international symbol-has left him oddly

faceless. No one has seemed interested in publishing the details of his life-as

if they would detract from his martyrdom. But pity is not understanding, and

Matthew's sorrow did not begin at the fence.

"He had emotional scars-he

had faced this kind of attack throughout his life," his friend Romaine Patterson

says. "He was a perpetual victim. That's how he became the person that he was."

The press was careful to portray Matthew as a special person who "happened" to

be gay. In fact these two qualities were deeply interconnected. "In some way he

was special because he was gay," Judy Shepard tells me, "because he had always

been different and that difference made him become more thoughtful, sensitive,

and empathetic." But "Matthew wasn't openly gay," his mother says. "He was

honestly gay. He didn't go around with a sign on-for one thing, he was afraid."

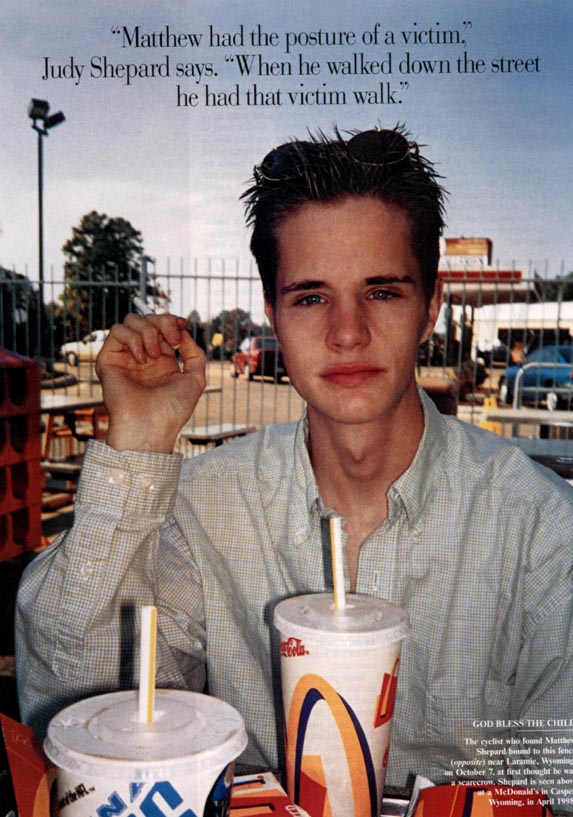

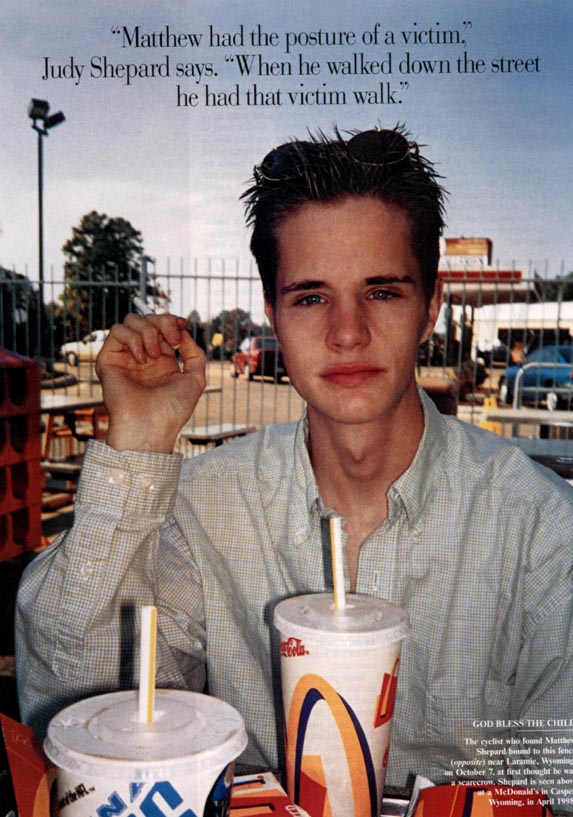

As well as suffering through a series of minor incidents throughout his

life, during his senior year in high school Matthew had been the target of a

vicious attack in Morocco. "He had the posture of a victim," Judy says. "He was

the kind of person whom you just look at and know if you hurt him that he's

going to take it-that there's nothing he can do about it, verbally or

physically. When he walked down the street he had that victim walk," she says.

"But if he was in an arena he knew about, like politics, he could shine with

self-confidence."

As a child growing up in the small town of Casper,

Wyoming, Matthew had always preferred the company of adults. He was friendly

with all his classmates, "but he never had a best friend," his mother recalls,

and she believes he needed that. "I think he always felt out of place." He was

teased for being small and unathletic. He was fascinated by politics: Gloria

Ningen, the family hairdresser, recalls how, when Matthew was in the second

grade, "he came into our shop and told us all how to vote [in the local

election]-and he knew. He knew the issues. We all thought he was going to grow

up to be president."

After Matthew's sophomore year in high school, the

family moved to Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, where his father was employed as an oil

safety engineer. Because there was no American high school there, Matthew was

sent to the American School in Switzerland-a progressive school where he studied

German and Italian and was involved in theater. "He was a snappy dresser," his

mother recalls. "He liked country, techno music, and neo-swing bands like the

Squirrel Nut Zippers. He was a good dancer and often went to clubs."

After graduation, he attempted to figure out where to go. "He had a real

restless, searching quality," Judy says. He briefly attended Catawba College in

Salisbury, North Carolina, and then Casper College, where a teacher introduced

him to Romaine Patterson, an outgoing lesbian at the center of a social circle.

"He was looking for a gay community and we took him in," Romaine says. When she

moved to Denver a few months later, he followed. He worked for a little while in

a telemarketing job, selling vitamins, and then quit. Romaine was a waitress at

a coffee shop, where he went and hung out for a couple of hours most days.

"He'd sit down and have these great conversations with strangers,"

Romaine recalls. "His focus was to help people who are less fortunate. He made

friends with a homeless man, and he'd take him to lunch once a week."

Matthew suffered from periodic clinical depression and looked into

living in Karis Community, a Denver assisted-living home run by mental-health

professionals, but he decided instead that he would move to Laramie and attend

U.W., his parents' alma mater. He felt that living in a small town would supply

some of the same sense of community, and that, as his mother says, "he'd feel

safer there."

Although he didn't come out until after graduating from

high school, Matthew knew he was gay from an early age. He told his friend Tina

Labrie how, during puberty, he had looked at some girlie magazines with a group

of friends. "He said he was curious to see women's bodies, too, but he could

tell that his friends were feeling something different-they were attracted and

excited in some way he wasn't. And then he noticed that when he looked at

pictures of guys he had that same feeling."

He struggled with how to

come out to his parents. Romaine, who grew up in the tiny community of Tongue

River, Wyoming, says that "when you come from Wyoming, parents haven't had that

education." They need to be "familiarized with someone who is gay."

Matthew's friend Brian Gooden says, "His mom tried to be supportive, but

she still had some misunderstandings, some hopes it was just a phase he was

going through. He desperately wanted acceptance and understanding from his

parents. I think he believed deep down that his parents would come round, but it

was taking more time than he wanted it to." Brian recalls how Matthew "tried to

drop hints to his parents that he was gay for a long time before he told them.

Once when he was home he left a gay magazine out on the coffee table, but they

put it on his bed without saying anything."

"That's absurd--I knew he

was gay all along," Judy tells me. She doesn't remember the incident, she says,

but if she didn't say anything it was because she wasn't surprised. When Matthew

finally called her from North Carolina in 1995 to tell her he was gay, she

reassured him she had known for years. She knew from the way he responded when

girls got crushes on him, as they often did, because he was friendly and kind

and treated them better than other boys did. She knew through what Matthew

termed "gaydar"-the mysterious way in which sexuality is sometimes successfully

communicated and understood-and she knew because Matthew, like most people,

wanted and needed to reveal his true self.

Judy Shepard never believed

that Matthew had a choice about his sexual orientation. "He said he didn't

choose to be gay-nobody would choose to be gay. It's a very hard life: you're

lonely, you're scared, you're discriminated against. He was searching for a way

to be happy with it. He was worried we'd be embarrassed or ashamed. I told him

to quit putting words in my mouth. He would feel guilty, an extra burden, but he

knew we would be there for him no matter what. There was never any question of

that."

It was more difficult for Matthew to tell his father, whom he had

always looked up to. "He and Dennis danced around it for a year," his mother

recalls. "It was a guy thing. Dennis would say to me, 'Why doesn't he tell me?'

Maybe in retrospect this wasn't the right decision, but Dennis didn't want to

ask him before Matt was ready to tell him. Matt made it so much worse by

building it up in his mind and causing himself all that anxiety. This was one of

his real flaws. He would invent a scenario and it would be the worst possible

scenario. The thing that hurt Dennis the most about it was Matt's reluctance to

confide in him.

"As a parent of a gay child you feel a profound sense of

loss that they're not going to continue traditional family life-the

daughter-in-law, the big wedding," Judy says. "But long before he told us, we

had already gone through that process. We felt he was our son and we loved him,

and you don't give that up because your life is not what you thought it was

going to be."

At U.W., Matthew decided to concentrate in political science with

a minor in languages. Tina Labrie, a married anthropology major whom he met at a

summer picnic, quickly became his closest friend; he fit into Tina's

family-taking to her husband and becoming the idol of her small children. She

responded to his warmth and vulnerability: "Whenever he learned of someone

suffering, it affected him personally," she says. She recalls a time when they

went to a matinee of Saving Private Ryan: "He was so sensitive to see the

violence and bloodshed he broke down and cried-afterwards he had to go home and

take a nap and take a shower. Then he came back for dinner and said he felt a

little better."

At U.W., Matthew decided to concentrate in political science with

a minor in languages. Tina Labrie, a married anthropology major whom he met at a

summer picnic, quickly became his closest friend; he fit into Tina's

family-taking to her husband and becoming the idol of her small children. She

responded to his warmth and vulnerability: "Whenever he learned of someone

suffering, it affected him personally," she says. She recalls a time when they

went to a matinee of Saving Private Ryan: "He was so sensitive to see the

violence and bloodshed he broke down and cried-afterwards he had to go home and

take a nap and take a shower. Then he came back for dinner and said he felt a

little better."

Tina was touched by the way Matthew would sometimes

solicit her opinion on his clothes, asking, "Does this make me look like too

much of a fag?" She says, "Making a positive first impression was very important

to him." She remembers how he once gave her a bottle of apple juice to open.

When she easily twisted the top off, "he said,'Great, there goes whatever little

bit of masculinity I have.' The look on his face was so cute, pouty but joking

at the same time." He was close to his younger brother, Logan, she recalls, from

whom he got "hand-me-up" clothing. "It was very important to [Matthew] to be a

good role model to [Logan]," Tina says. Matthew was excited that Logan was going

to come to Laramie the next summer, and possibly attend U.W.

She was

pleased when he told her that her husband, Phil, "was the first straight guy he

ever felt wasn't afraid of him. He asked me, 'Have you ever had a fake hug?

Straight guys hug as if they're afraid being gay is contagious and they'd catch

it.' He said he'd never hit on a straight man, even if he was attracted-he just

wanted to be friends with them." Matthew told her that before the bar incident

in Cody he had been assaulted and raped in Morocco. He asked her, however, not

to tell Phil, because he was afraid Phil would disapprove of him.

During

his senior year in high school, Matthew and three classmates had gone to

Morocco. Unable to sleep one night, Matthew had gotten up and walked to a nearby

coffeehouse, where he chatted with a group of German exchange students. On the

way home, a gang of locals accosted him, raped him six times, and took his

shoes.

He worked with the Moroccan police to catch the perpetrators, to

no avail. But as he often did, Matthew inspired compassion in his troubles. "The

police could have been awful, but they weren't," Judy says. One of them gave him

a gift of a picture of a Moroccan on horseback, a gesture which touched Matthew.

After the rape, Matthew stayed with his parents in Saudi Arabia for a while and

underwent therapy, but he continued to suffer anxiety, flashbacks, and

nightmares, from which he was unable to free himself.

"He was never the

same after Morocco," Judy says, "and neither were we. We were always worried

about his physical safety and his mental state-that he would despair and hurt

himself. It seemed to him it was taking forever to feel safe."

Matthew

told Tina he was haunted by the question of whether the perpetrators had ever

been caught and what had happened to them. "He was impressed with the apartheid

hearings in South Africa-how Nelson Mandela offered forgiveness as a step

towards ending the violence. He thought that was a cool revolutionary idea,"

Tina says.

After the rape, Judy says, Matthew suffered from periods of

paranoia. "He would say, 'My fear is irrational, I shouldn't be afraid of

people.' And then he would over-compensate for his fear by making himself do

something he shouldn't"-a kind of counterphobia, in which he'd recklessly put

himself into the hands of strangers. Romaine recalls how he'd sometimes take

risks with his safety, such as walking alone at night in Denver, explaining that

he didn't want to be circumscribed by fear. On the family vacation to

Yellowstone last summer, he went to a bar in Cody by himself late one night. He

drank heavily, left with some strangers, and eventually passed out, with

flashbacks of Morocco. He awoke, uncertain of what had happened, with a split

lip and bruised jaw. Later the bartender told the police that Matthew had made a

pass at him and that he had therefore been compelled to hit him.

Matthew

was "cautious when it comes to dating," Romaine says. He had only had one

serious relationship, while he was at school in North Carolina, with a man who

made him unhappy. Judy worried that he could be vulnerable to an emotionally

abusive relationship. "Matt allowed [his first boyfriend] to hurt him again and

again."

It was through America Online last summer that Matthew met Brian

Gooden, a 36-year-old optician from Denver. Brian says that usually such

communications take a sexual turn immediately: "It's 'What's your stats, when

can I come over?'" He and Matthew traded questions for an hour, and then Matthew

told him he thought he was really going to like him because Brian hadn't hit on

him. They corresponded and talked regularly for several months. "Matt was

hesitant to meet," Brian says. "I asked him why, and I could hear his voice

trembling. He told me he was afraid something a lot more serious would happen."

Matthew was worried that he'd become too attached, too dependent, as he had the

tendency to do in some relationships. "Finally, he invited me to Laramie for

three days," Brian says, "from October 9 to 12."

As September closed,

Matthew was depressed. "Midterms were coming up," Tina says. "He was afraid of

failure-he felt all this pressure not to fuck up."

"We were really

hopeful at the beginning of the semester," his mother says. Matthew suffered

from attention deficit disorder, and had always struggled as a student. "A 'B'

for him was a real achievement," Judy says. "He'd have a panic attack and would

miss classes and then get so far behind there was no way of catching up. He had

a habit of moving, instead of staying in one place and making things work.... He

was going to try as hard as he could in Laramie, and if it didn't work, at the

end of the semester we were going to try something different-perhaps more

intensive therapy. He was only a month into the semester when he died, but he

was becoming more sad and withdrawn."

Although he had a psychiatrist who

prescribed medication for him, he was looking for a therapist he could really

talk to. "He had seen somebody at the student health center, but she just wanted

to talk about his academic goals-she didn't seem to really understand his

depression," Tina recalls. He had been hospitalized several times for depression

and suicidal ideation; the previous summer he had checked himself into a

hospital in Laramie. He was taking Effexor, an antidepressant, and Klonopin, an

anti-anxiety drug. Judy was concerned that the medications weren't working and

that Matthew would drink, "and the combination of the drugs and the alcohol

would deepen his sadness."

On Friday, October 2, Matthew asked Tina to

accompany him to the Tornado, a gay bar in Fort Collins, Colorado, in Doc's

limousine. Matthew owned a 1978 Bronco, but he disliked driving it. "He said he

felt lost in it," Tina says, "a little guy in a such a big truck." But he was

also "worried that in renting the limousine he was being selfish. I'd never

ridden in a limousine before. I said, 'If you can't pamper yourself, think that

you're pampering me.'"

At the Tornado, Tina and Matthew sat in the

garden talking for an hour about life goals and dreams and death. He told her

how guilty he felt about having been born into a well-off family, and she said

that he could use his resources to help people. Matthew told her that if

anything ever happened to her and Phil, he'd like to be the guardian of their

children. Then he asked her if she would take his cat, Clayton, if something

ever happened to him.

"I knew how much he loved his cat. I said, 'O.K.,

from now on, when we move into an apartment we'll make sure we get ones that

allow pets,' thinking he'd outlive Clayton and we were talking about some later

cat."

Inside the Tornado, several men approached Matthew. The first,

someone warned, was H.I.V.-positive and didn't always tell people, so Matthew

shied away from him. Matthew had told Tina that he was worried about H.I.V. and

always used protection. "Then this other guy came and stuck to him like glue,"

Tina says. "Matt didn't like him, but he couldn't figure out how to get rid of

him and still be polite."

Riding home in the early hours of Saturday

morning, Matthew told Tina he felt that "if he died no one would even notice

until his bills weren't paid, and then his parents would call up to bitch and

then realize he was dead. He felt nobody cared what he was going through. He

told me about his little suicide plan-he would take all his Klonopin at once

with alcohol. I asked how often he had been thinking of this, and he said quite

a bit. It seemed like he was pretty close-closer than the way he described other

depressions." Then he leaned his head on Tina's chest and fell asleep listening

to her heart beat. "I'm like, Wow, I have a friend who's not afraid to touch

me," she recalls. "Most friends seem to think affection goes on only on special

occasions."

When they got back to Laramie, Tina asked if she could sleep

on Matthew's couch so as not to leave him alone. Saturday morning she awoke to

hear Matthew in an argument on the phone with his mother, who was upset because

he had overdrawn his bank account-a pattern of his.

"Afterwards he felt

really bad because he lost his cool and started cussing at her, which he had

never done before," she says. "That afternoon I had to go home because Phil had

a cold. I asked Matthew if I should call somebody for him, and he told me that

he knew deep down, he'd be O.K.-that he could get through this." She asked him

to promise he wouldn't do anything to hurt himself until she got back, and he

promised.

On Sunday, he called his mother and apologized, telling her,

"You're right, I've got to be more careful with my money. I promise I'11 do

better." Then he said, "I love you, Mom-I'11 talk to you later."

Judy

weeps now, recalling her last words to her son. "I love you, too. Be safe," she

said. "That was my mantra to Matt-be smart, be safe."

That afternoon,

Tina tried calling Matthew When she got no answer, she went to his apartment and

then searched downtown, where she was relieved to find him in a restaurant.

On Tuesday, Tina had caught a cold and stayed home all day. She tried to

reach Matthew that evening, but she wasn't feeling well enough to go look for

him. Wednesday morning she started calling him right away, and became anxious

when she got no answer.

After debating with herself, at seven that

evening she decided to go ahead and call the police. She told the officer that

she had a friend she wanted them to check on. The officer asked for his name,

and when she told him, a long silence ensued. Then the officer started asking a

lot of questions, like whether there were any people in town who didn't like

Matthew. "I'm thinking these aren't normal questions, but I try and answer. And

then they say they're going to send an officer over to talk to me. And then I'm

really scared. I don't want them to send an officer to me, I want them to send

an officer to look for Matt. When the officer gets here she doesn't tell me

anything, but she starts asking more questions, running all these names by me,

asking whether I knew Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson. But I had never

heard of them."

Next

Page At U.W., Matthew decided to concentrate in political science with

a minor in languages. Tina Labrie, a married anthropology major whom he met at a

summer picnic, quickly became his closest friend; he fit into Tina's

family-taking to her husband and becoming the idol of her small children. She

responded to his warmth and vulnerability: "Whenever he learned of someone

suffering, it affected him personally," she says. She recalls a time when they

went to a matinee of Saving Private Ryan: "He was so sensitive to see the

violence and bloodshed he broke down and cried-afterwards he had to go home and

take a nap and take a shower. Then he came back for dinner and said he felt a

little better."

At U.W., Matthew decided to concentrate in political science with

a minor in languages. Tina Labrie, a married anthropology major whom he met at a

summer picnic, quickly became his closest friend; he fit into Tina's

family-taking to her husband and becoming the idol of her small children. She

responded to his warmth and vulnerability: "Whenever he learned of someone

suffering, it affected him personally," she says. She recalls a time when they

went to a matinee of Saving Private Ryan: "He was so sensitive to see the

violence and bloodshed he broke down and cried-afterwards he had to go home and

take a nap and take a shower. Then he came back for dinner and said he felt a

little better."