![]()

social criticisms

by vicente-ignacio de veyra iii

Passion for Profit (and Vice Versa)

The

prolific Filipino ceramic artist Ugo Bigyan (he prefers to be called a

mere "potter") has always espoused a 1:1 ratio for his entire

output, the one part being on the side of business, the other on the side

of art. This is not an alien doctrine to most successful artists, although

some of them would deny having put an equal premium on

"commercialism". Bigyan's commercial items (he supplies three

Glorietta stores, among many other malls' stores) are neither crass nor

condescending in their exploiting and feeding a supposedly less academic

market. Quality is distributed to all classes and markets, that's his

products' policy. And as for my use of the word "exploiting", we

must remember that in marketing management, the word is seldom used in its

negative, irresponsible sense. And as for my saying "supposedly less

academic", we must likewise remember that the market of higher-end

artistic products are not necessarily always academicized.

In a capitalist environ, or -- if you will -- a free enterprise system,

all art necessarily becomes commercial. Or, to be more blunt, all art is

commercial. Anti-commercial art can be categorized into two: one

patronizing a limited (therefore unprofitable) cognoscenti class market which includes both learned and merely

pretentious elements, the other exercising a form of rebellion against the

role money plays in art or otherwise flaunting a freedom from the

necessity of selling. Some so-called installation art (a genre which

blossomed in the '70s) has not always decried the money influence, for we

might remember that the US' National Endowment for the Arts and such other

funding institutions offered hefty sums to artists who wished to practice

this traditionally non-profit form of art. On the other hand, those who

were vocal (in their installation-art practice) about the supposed

corruption of painting and sculpture were able to declare their stand from

positions that either maintained day jobs or otherwise solicited

maintenance fees from their family wealth or similar contributions. I can

also say this about myself, for having been able to write my six online

books of poems and one short story collection, all products sans profit.

The day job not only allowed me the weekend luxury of writing but likewise

access to office internet facilities. :-) When Boris Pasternak wrote in a

poem "And for your noble work no payment claim,/ Your art alone your

wage", I wonder what sort of poet was in his mind -- a doctor-poet

like him? a carpenter-poet? His medical practice, a half-commercial

venture, sustained his art, making his art quasi-commercial in the final

analysis. The only true anti-commercial art would be one that will

do it once and die, unable therefore to do it again. Doing it again would

solicit the question as to how one was able to do it again. What sustained

his nutrition through the weeks?

Of course, what is often disparaged as commercial is art that either is

not or has been downgraded or perceived to have compromised with -- to

satisfy the profit motive of -- producers, patrons, or dealers. Or the

patron or dealer in oneself. But even such downgrades do not necessarily

produce lesser art. Picasso's ceramic plates have often been

touted as some of Picasso's commercial works, although certain radical

criticism would regard Picasso's entire body of works as wholly commercial

for the works' patron-friendly colors. Picasso's plates would now command

serious study from many an art critic or art aficionado.

Picasso plates

"...who we buy is a

reflection of ourselves. Who we choose to sell to reflects whom we look up

to. We are judged thus, but mostly by ourselves, in the now and in the

later."

So

many an artist has practiced what business and product marketers refer to

as positioning. And this with a brave struggle. Having come up with a

painting, one has decided to do more of the same and so position oneself as

a painter of this type of paintings. Commercial? Perhaps. But so is

everybody else in choosing their career, their success paths, their

expertise. And they do so with a brave fight.

Commercial motivations, admitted as so or not, subconscious or vocal, have actually produced the best and the worst commodities in our time. And, oh, to actually be impartial, "commercial motivations" were not absent in communist countries; were, in fact, what kept everybody there working.

So, understand the artist's own profit motives. And likewise his oft-unaware and thus not so self-criticial position towards his commercialism. Regard him/her as the coffeeshop-owner making your special cappuccino really really special. If you love your coffee, you wouldn't call it a commercial cappuccino, would you? Often, it's poor quality that dictates our suspicion of a high degree of "commercialism" or corruptibility going on, even as the cappuccino-maker simply thought he/she was really great at making cappuccinos. And -- like the bad artist who has been patronized by so many buyers who thought they knew what was great art -- forgot that he/she was really just a product of commercialism's supply and demand principle.

All art is commercial. If your buyers are happy, they wouldn't call you commercial. Therefore, since intrinsically all art is positively commercial whether we like it or not (and whether we're aware of it or not), so-called negative "commercialism" or corruptibility in an artist or coffeeshop restaurateur becomes nothing more than a subjective view in the practice of buying.

Recently, there's been this brouhaha over a supposed mercenary spat between Church elements and the folk painter Nemesio Miranda. Miranda, commissioned by Church elements to do a painting for the EdSA Shrine, allegedly had been consistent in bidding for a high price (P400,000 plus) in the simple cleaning and a much higher price (P1.5 million) in the full restoration of the painting he was commissioned by the Shrine to do. The Church allegedly haggled with him (a thing which Miranda denies, claiming the Church could actually have negotiated with him instead of not). The spat came forth when the Church elements concerned decided to do their own restoration, claiming they couildn't afford Miranda's quotation; they said they had every right to do whatever they wanted with the piece since it was theirs. Miranda cried foul, saying it was his artwork and the restoration omitted certain parts (no, practically erased them with a white daub). It was his concept, he said, and by the restoration his concept was denigrated.

Clearly, Miranda (and his defenders in the press) missed the point. Forgetting he has consistently been acting the artist aware of his commercialism (by asking to be paid for the restoration of his own concept presupposed that his concept was less valuable than the payment), Miranda insisted it was an ethical question. Suddenly, Miranda was on the side of artists who keep on claiming that their art is purely conceptual and only secondarily commercial. Obviously, Miranda failed to see that the issue was a purely commercial question. This is assuming that the Church elements really did haggle with the artist. The question is this, which I shall henceforth illustrate by way of an idea for an art project:

I will create a painting and exhibit it at a gallery. Before anyone can buy it, I shall buy it myself. Then I'll paint over it. Then I shall exhibit the redid painting, go through the same process of buying it myself and ruining it. And on. And on. Till I tire of it. I can do whatever I want with the piece because I bought it and therefore it's mine. I bought it and rebought it, and everytime I bought it I redid it. Also, I can do whatever I want with the painting because I was the artist. That would be the height of ethics, then. Permission unnecessary because nobody asks permission from oneself.

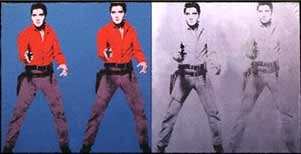

patron-delighting

Warhol painting

And if I can do this, I shall have demonstrated a truly non-commercial art that -- in the manner of Tarantino -- shall have successfully used commercialism as my material and thematic content. I might thus achieve for the middle of this decade what the pop artists of the '60s (Warhol, Lichtenstein, etc.) achieved with kitsch, pushing pop and kitsch and the trampy up as valid material for artmaking, in my case pushing what I'd probably immodestly perceive as the work of my own genius (reworked everytime in a kind of self-criticality) as valid material for a portrait of artists' passion for concepts. But I won't be so hypocritical and claim freedom from commercialism, for I shall remain aware that what made me buy my own painting and abuse it was a certain luxury in my convent, free from hunger and not denying that I can afford any quotation from any expensive school of art that shares my taste (since that school of art that shares my taste is only my own, cheap self).

If all art is commercial and we cannot escape it, from living with art, then, we can see one final enveloping moral lesson. In the commercial world, one is judged by what he sells. Also by what he buys. In this sense, then, who we buy is a reflection of ourselves. Who we choose to sell to reflects whom we look up to. We are judged thus, but mostly by ourselves, in the now and in the later. And the reason why there is no law against an art patron's right to ruin an artpiece he bought is this issue of trust between the buyer and the seller who in essence have been morally (not legally) married to each other. The judges' sentencing is seen in the presence or absence of a continuing happiness. For, as we said, if you like your coffee,... but the Church hates divorces.

Marketing

men advise us to make good products as a first step to market success.

However, in the same breath they'd say that if there is no market for our

products, then they can always make one. From Piccaso let's fast-forward to

the '80s, when several artists marketed their stuff as "ugly

paintings". Whether it was from a disgust for the burgeoning trend in

patron-friendly pretty coloration in many of the paintings of that decade,

or whether it was from an awareness that there was a growing part of the

market who had that disgust and had become bored with paintings in general,

I do not remember.

And as for art that is not, in "popular cinema" for example (as

against "art cinema") exists such prejudicial tags as suspense

thrillers, horror, romantic comedy, and so on. Quentin Tarantino delivered

the loudest statement for this issue with Pulp Fiction,

demonstrating that poetry (linguistic and visual) is possible with

established Hollywood pop cliches and formats. Katheryn Bigelow has done it

too in her lesser-known films. Recently, in Kill Bill, Tarantino

demonstrated further that there can be such a thing as art-for-art's-sake

cinema that uses Hollywood formats. Which, by the way, can also be regarded

as pure, blind entertainment. The corollary statement is perhaps that

Hollywood formats have maybe always been more about the art than the

stories: the action itself was more important to audiences than what the

action was all about. Consider that up till Kill Bill, such art for

art's sake claims have only been associated with French and German short

films (filmic films) that showed a lot of those blurs, scratches on the

film, editing flairs, double exposures, swinging cameras, and so on, that

seemed fraught with the obsession to bring painting and Pollock into the

photoplay medium. Tarantino thus achieved for the turn of the millennium

what the pop artists of the '60s (Warhol, Lichtenstein, etc.) achieved with

kitsch, pushing pop and kitsch and the trampy up as valid material for

artmaking.

scene from Kill Bill

There are a lot of art that are simply bad and deserve to be lambasted as kitsch, but using kitsch as material for good art is a different thing altogether. Laying Mona Lisa tiles on one's kitchen walls would be kitschy. Doing so and doing it in extremis to come up with a so-aware contextual statement on the kitsch-ification of the Mona Lisa in the age of the tourist would be using kitsch practice as material and thematic content for a good art concept.

Statements and concepts abound in good art today, in New York as well as in Manila. And most of these are for sale. In the same manner that novelists sell their novels, filmmakers their films, though it's usually painters who get rich fast.

Good art is commercial without being "commercial", or, as Tarantino has loudly shown, one can be "commercial" to achieve good art out of that commercialism. The painter Piet Mondrian produced a similar resultant with his work in a less-aware fashion. Five large paintings by Mondrian and his statement would already have been clear in that age when art was still covered by newspaper journalism. But no, he had to paint more, and still more! "Commercialism"? Perhaps. But in the end he demonstrated that the simplest, most basic formula can attain a rich number of variations to ultimately make up a collective output that can be regarded by the forgiving as one single artistic epic of an opus, profit-motivated or not.