|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

VIETNAM, CHANCE, AND THE TRUE VALUE OF A MOTORBIKE

I was sitting idly on my favorite Washington Island perch,

the coffee house porch, on an almost spring April morning. I

was cradling my first cup of the day, robust steam wafting into

my nostrils. I glanced at the open copy of the New York Times

someone had abandoned on the side table. Above the fold it read,

Three Marines Killed in Fallujah. Below, near the bottom, Democrat

Alleges Vietnam Parallel. That little bit, that was enough.

The pace of activity within my field of vision was what you'd

call relaxed. Almost nothing was moving. A car piloted by an elderly

woman straining to see over the steering wheel slowly approached

from the direction of the thrift shop, made its way to the intersection

and turned toward the heart of town. For no particular reason

I decided to time the interval until the next car passed. Four

and some half minutes later Constable Tyler slowly rounded the

bend in the Island cruiser. He crept on by with a wave and a smile.

The fact that he didn't stop suggested to me he was in high speed

pursuit of that suspect gal in the afore mentioned vehicle.

The scene got me to thinking just how different human lives can

be, and about the vicissitudes of chance that had put me on this

porch. In recent months my idle reverie had inclined toward such

sophomoric musing. I'd been sitting on this porch in early February

when the pace of things had been even less frantic. Seventy two

hours later a taxi had plunked me and my worn satchel down on

a street corner in central Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Now, there may be places where everyday reality differs

more from some winter's afternoon on Washington Island, but I

doubt such places are on this planet. As is my way, I'd given

little thought to what such an abrupt transition might mean. The

fetid air, the heat, the smells, the noise, combined to leave

me lightheaded. I pulled my satchel away from the broken concrete

curb and plopped myself down. In front of me moved an almost unbroken

swarm of honking motorbikes, bicycles, cyclos (rickshaws), and

an occasional truck. There could not have been more than a foot

separating the darting vehicles. Most proceeded on their side

of the road, but a goodly number appeared to find driving against

traffic more advantageous. At the intersection an intricate dance

of daring somehow allowed one mass of humanity to meld into a

similar mass proceeding in a cross direction. No lights, no signs,

no helmets, no rules whatsoever. Utter and complete chaos. As

I watched, it seemed inevitable that the intersection would fill

with broken bodies. Surely all the horn blowing was a prelude

to brawling, on a very large scale. Had the sidewalk not proven

equally perilous I may have remained, immobilized, right where

I was. When I regained my balance, I realized that my satchel

and I were impeding a complex world of sidewalk commerce that

extended as far as I could see in both directions. I would need

to find a refuge away from this deafening din and mount a search

for my missing sensibilities. Such was my introduction to Vietnam

and it remained pretty much like this for the month of my meandering.

Some months earlier my wife had posed the eminently reasonable

inquiry. "Why Danny, of all the places you could visit, do

you want to go to Vietnam? "I'm very curious about the place,"

I told her, "I've always been very curious." That reply

meant one thing to me, another to her. My wife's forty four,

I'm fifty-four. Her experience had been different. For me the

very word "Vietnam" pushes play on a private home movie,

replete with a soundtrack, that I made long ago. In these snippets

I'm always young, so I never mind the intrusion.

If you're in your fifties, Vietnam has likely loomed large.

I'm not speaking here about the relative few who had gaping holes

blown in their lives. That's a different matter altogether. I'm

referring to the rest of us. That huge bulge on the population

curve that came of age during the moral and physical squalor of

the Vietnam War (or the American War as the Vietnamese choose

to call it). We were, I suppose, all dealing with the predictable

developmental issues of growing up and separating from our families

of origin. The war and the adult world that had fermented it,

provided the perfect foil. One could make the argument that much

of the passion of the time was attributable to the unique convergence

of demographics and events. One could. I wouldn't. There were

an awful lot of us, so many in fact that we came to occupy a mutually

supportive, parallel universe. This heady brew, and the war that

gave it focus, was the most consuming reality of my young adulthood.

I managed to avoid service in Vietnam. Like most of my contemporaries

I maintained circumstances that allowed me to avoid being drafted.

I remained a college student and later drew a middle of the pack

lottery number that allowed me to avoid making the hard choices.

It's true that some took a principled stance in either volunteering

for, or refusing to go to Vietnam. I admired both, but I didn't

really know many of either group. Sentiment against the war prompted

many I knew to become antiwar activists, and a few to become

extremists. Most just wanted to stay out of the fray, the one

at home and the one in Asia. A few, like the resolute Mr. Cheney,

busied themselves with "other priorities." They supported

the war as long as it was fought by other peoples children. I

didn't personally know anyone killed in Vietnam. A boy several

doors down from my parents home was killed in the Mekong Delta,

but I'd only met him in passing. I was always acutely aware that

going or not going to Vietnam was purely a matter of chance and

had nothing to do with fairness. Whatever guilt I may have felt

watching others I'd grown up with plucked from their lives was

vastly overshadowed by the relief that it wasn't me. I was very

long on self righteous principle in those days, but in truth my

aversion to service had a much cloudier basis. I'd watched Vietnam

on nightly TV since I was fifteen and the whole deal flat out

scared the bejeesus out of me.

Many of those images remain clearer in my memory than events

of a year ago, and they provide the temporal benchmarks of my

young adulthood. I was fourteen when my civics teacher brought

in the AP photo of the first Buddhist monk to set himself ablaze

on a Saigon street. Fifteen when the evening news brought us footage

of the first American combat troops going ashore near Danang,

initiating the "casualty count" as a standard feature

of the day's news wrap-up. Seventeen when General Westmoreland

apparently mistook a train coming right at him for light at the

end of the tunnel. Eighteen when the news cameras captured the

specter of our South Vietnamese ally putting a bullet into the

brain of his bound and kneeling "suspect" on a crowded

Saigon street. Eighteen when Johnson threw in the towel and the

Democratic Convention exploded in Chicago. I was nineteen when

live footage of the Tet offensive brought us that naked and burning

Vietnamese child running down a Saigon highway, and the airport

tarmac covered with two thousand American bodies awaiting shipment

home. Twenty when we learned that Nixon had secretly invaded Cambodia.

Twenty one when the New York Times printed the Pentagon Papers,

confirming what most everyone already knew. The government's ability

to tell the truth had been an early casualty in the conflict.Twenty

four when Nixon slunk away under the weight of so many big fat

lies. Twenty five when the last American helicopter ascended from

the US embassy roof, like a mamma sparrow abandoning her chirping,

hungry hatchlings. Add to this the spate of horrific Vietnam era

movies I felt obliged to sit through in recompense for not having

shouted "FIRE" loudly enough. The reader can perhaps

understand why I felt it prudent to give the Vietnamese twenty-five

or thirty years to cool off before paying them a social call.

I had always wondered how such colossal misjudgements could

have been made. Had nobody ever bothered going there to look around?

Did nobody speak French? Twenty four hours in Vietnam only deepened

my incredulity. The streets teem with purpose and the people

with dogged determination. Nobody but me lazing away the morning

on the coffeehouse porch. The amount of ingenuity and effort that

the average person has to muster just to survive and provide

for their loved ones appeared daunting. They were the hardest

working, most tenacious people I'd ever seen. What's more, they

appeared to endure their demanding lives with considerable grace.

I wandered through dirt poor, densely congested urban neighborhoods

and remote backwaters and never felt nervous about my personal

safety, (the fact that the government deals quickly and harshly

with street criminals likely had something to do with this). I

never saw an angry exchange despite the rigors of daily life.

They seemed blessed with an enviable equanimity of temperament.

I found myself wondering what our legions of motoring hot heads

would do if afforded a real reason for upset.

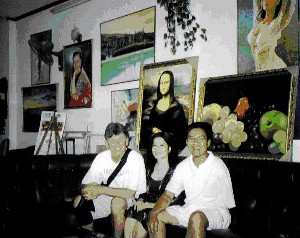

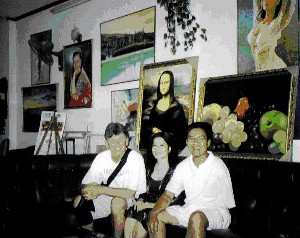

The people I became acquainted with in Vietnam were extraordinary.

Take for example Tan. He operated a small Guesthouse in an alley

in central Saigon. He had lost his right arm, a good part of his

shoulder, and other anatomical bric-a-brac as a soldier in the

South Vietnamese Army. His wife told me that despite seven operations

he'd been in pain for twenty-five years. Yet, I could not dissuade

this man from carrying my bag up two flights or from doting on

me in a host of unnecessary ways. The loss of his painting arm

had caused Tan to suspend his dream of becoming an artist. He'd

stopped painting for many years and then took on the arduous

challenge of training himself to paint with his left hand. He

supplements his meager income as an inn keeper by painting flawless

replicas of the old masters and selling them at the market. He

puts asides his modest painting proceeds in the hopes of someday

sending his daughter to school abroad.

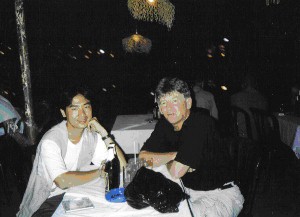

Or, my young friend Quan. I hired Quan to be my guide while I was in Central Vietnam. I didn't really want a guide but Quan was so earnest and such good company that I paid him a ridiculously small sum to hang around with me for a few days. He was twenty-two, and had studied some kind of a tourism curriculum at the University in Danang. He made about $40.00 a month plus tips at this vocation. Quan told me that he sent one quarter of his wages to his widowed father in a rural village and another quarter to his younger brother studying in Saigon. A devout Buddhist, Quan taught the Temple youth group and was an avid fan of traditional Vietnamese music and theater. He was also very fond of American heavy metal music. Quan acknowledged that life in his country was hard but he was optimistic about the future. I would rent a motorbike and tell Quan to take us wherever he wished. On one such outing I asked Quan if he had a sweetheart. He hesitated before replying, then said wistfully, "you cannot get a sweetheart without a motorbike." For whatever reason, I found this admission heartbreaking. As best I could tell Quan would not be getting a motorbike any time soon, if ever. His tone suggested that he was painfully aware of this. I tipped Quan as well as I could when it was my time to move on. He showed up at my hotel that evening with presents for me and for the members of my family. He insisted that I be his guest for dinner. When we arrived at the restaurant he'd chosen, Quan produced a CD from his bag and instructed the waiter to play it on the establishments sound system. My friend Quan, who didn't speak English very well, then stood and sang me a flawless version of Hotel California.

Or consider the young boy I met on a ferry somewhere in the

Mekong Delta. I've got some walking problems that get worse in

the heat. My legs had pretty much given out on me and I wasn't

sure I'd make it up the ramp before the boat left without me.

I was hobbling along clutching the rail when a young boy of about

nine or ten came out of the crowd and took my arm. He didn't say

anything, just patiently walked with me and found us a seat on

the deck bench. He sat with me for the crossing though I don't

think he had a reason, other than helping me, to go to the other

side. He smiled shyly at me and said little. He seemed intensely

curious about my appearance. He stared at me until embarressment

compelled him to avert his eyes, then he stared some more. He

didn't want anything, wasn't selling anything, just a kind and

curious little boy.

I suspect that Asia shocks most first time visitors. It did

me, and for a short while the utter strangeness of the place scared

me. My initial trepidation quickly turned to fascination. As is

true in most third world countries, there are lots of people in

desperate straits begging on the streets. This took some getting

used to. On day one I responded to whoever approached me and

looked needy. The result of this largesse was a run on the bank.

It was akin to the announcement of a "blue light special"

at K-Mart. Even after I had adjusted my threshold of response

to persons with debilitating physical abnormalities and multiple

missing limbs, I gave away a substantial amount of "dong"

each day. I've heard sophisticated arguments for not encouraging

such begging. It's been my experience that these arguments are

most forcefully made by the stingy.

The government of Vietnam is still ostensibly communist, but long ago gave up the dream of creating a socialist Utopia. The economic "opening" in 1996 has made almost everyone in Vietnam an entrepreneur of one sort or another. Impromptu Mom and Pop restaurants spring up on every available meter of unoccupied sidewalk. "One folding chair no waiting" roving barbers are ever-present. Pirated, cheaply copied, books appear to be a cottage industry. They are pressed on western tourists by very young street kids, most of whom contend they are orphaned and homeless. They have a practiced ability to size up their quarry on the move and pull from their stack their one best shot. It would appear that I telegraph a fondness for Graham Greene. The military ( who appear also to be the police), lacking anything tangible to hawk, appear to interpret "economic opening" as license to extort small bribes for inconsequential infractions of petty regulations.

I spent a morning in Saigon visiting Ho Chi Minh's Mausoleum. Uncle Ho died in 1969 and despite his express wishes to the contrary, he's been stuffed and placed on public display. Everyday thousands of Vietnamese journey to Saigon and line up for an opportunity to file past their beloved leader. Every two years he's sent to Russia for some kind of a general sprucing up. Despite his recent refurbishment, I must report that Uncle Ho looked pretty darned peaked.

I spent a good amount of time watching people and traffic from the vantage point of the ubiquitous sidewalk cafes. My favorite time was late afternoon when the streets filled with beautiful young Vietnamese women in their traditional white dress. They would float by, like apparitions on their motorbikes, long hair streaming in the wind. In Hanoi I became particularly fond of a sidewalk café where, for the price of $1.20 (American), I could sip a Nehi orange soda and receive a half hour head massage while watching young Vietnamese play ferocious badminton in the park across the way.

I floated for several days on an ancient boat into the Mekong Delta. The unfolding life on the river and on the bank likely looked as it had fifty or even five hundred years ago. A young woman in black pajamas, the daughter of one time North Vietnamese regulars, poled me through a labyrinth of narrow jungle waterways to the site of a former guerrilla base in the heart of South Vietnam. Remnants remained of the underground medical facility, the command hut, and barely discernible underground bunkers. I crawled around in parts of the extensive tunnel system that the VC built to connect them with the North. Later the young woman took me to meet her Aunty in the nearby village. Aunty had been born in the tunnels in 1968 and had lived the first four months of her life there. She served me coffee and was kind enough not to inquire whether I might, perchance, have been one of those lobbing bombs at her snug underground warren.

Many of the motor bikers on the roads are interested in providing

transport for a fee. This seemed unnecessarily risky and I usually

declined such offers. One afternoon I was particularly worn out

and decided to accept the proffered ride. I attempted to communicate

my destination. He nodded in comprehension, turned the bike around

and accelerated into the oncoming traffic. This apparently was

the quick route. Realizing the futility of objecting, I just

closed my eyes.

I bought passage on a rickety old vessel for

a two-day cruise of Hailong Bay near the Gulf of Tonkin. This

was a surreal dream scape; huge limestone spires, shrouded in

mist, pierced the dead calm waters of the bay and rose hundreds

of feet straight up. The appearance of a dragon seemed not only

possible, but likely. On the second morning I awoke early to watch

the sun come up. The crew's cook was preparing our breakfast at

the stern of the boat. I could see that he was scraping the fur

off some part of animal anatomy that appeared to have a hoof on

the end of it. Fortunately I had a store of Snicker bars for just

such a contingency.

I spent several days wandering around the ancient

Chinese trading village of Hoi An. At dusk the shops and homes

are ablaze with colorful silk lanterns. The streets seem dreamy

and magical, perhaps indelibly made so by the opium trade that

once flourished there. Hoi An is a place renowned for it's textiles,

tailors and seamstresses. A Dutch acquaintance commissioned two

custom fitted, tailor made suits that were made to perfection

in two days for a total of $40.00 (US). Unfortunately, I had no

use for new suits. One afternoon I decided to buy a sack full

of inexpensive toys at the market and pay a visit to the orphanage

I'd spotted while biking on the edge of town. Two Buddhist nuns

do their best to care for more than seventy children many of whom

appeared to be severely developmentally disabled. I was immediately

swamped by needy kids and rather quickly concluded that my decision

to drop in had been naive and decidedly unhelpful.

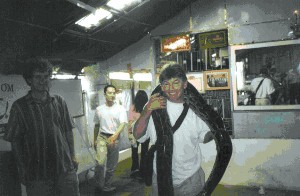

I went twice to see the Hanoi Water Puppet Theater. The first time a large rat stole the performer's thunder by cavorting at length outside of the puppeteer's view, in full view of the audience. The following day I joined a small excursion for a tour of some outlying Buddhist antiquities. We stopped for lunch at a café on a rural highway. I had become somewhat accustomed to the unexpected but I was taken aback when an eighteen-foot python slithered out of the kitchen in the direction of my table. The proprietor found my alarm quite amusing, and after much reassurance, convinced me to pose for a photo with this big fellow hoisted onto my shoulders. This photo has done more than anything else could to convince my nine-year-old boy, Sammy, that his daddy is a very brave man.

When I got home, I would regale my family, whether they wished

to be regaled or not, with my memories of Vietnam. My eighteen-year-old

daughter, Janey, found Quan's romantic conundrum particularly

disturbing. "Why" she wished to know," don't you

stop sneakin' around smoking cigarettes and put the money you're

spending ruining your health toward buying Quan a motorbike?".

"Well," I told her "they aren't cheap. The coveted

Japanese jobs cost a lot more than they cost here, and the cheaper

Chinese knock offs don't last long." "Well," she

responded, "get him one of the cheap ones. If he gets right

to work, and pays her the attention a girl deserves, he can probably

seal the deal before it breaks." I am intending to explore

this inspired counsel.

It's May now and I have resumed my tireless vigil on the Washington Island coffeehouse porch. I'm sippin' a cappuccino that costs twice what the average Vietnamese makes in a day. Janey phoned me last night. She's finishing up her freshman year at college and frantically trying to tie up the semesters loose ends. She told me she was having difficulty focusing on her work. She said "I can't get those horrible, horrible pictures of those Iraq prisoners out of my mind. Pappa, who could do such a thing? " She wanted to know."What, in Gods name, is happening over there?" I would have liked to have comforted Janey, to have told her that such lunacy was an abberation. That reason would prevail. That those leaders acting in her name on the other side of the world were not malevolent. She would, however, recognize this as the disengenuious nonsense that it was. It didn't seem useful to tell her that more than a few of the savvy crowd that has orchestrated Iraq's "liberation" cut their policy wonking baby teeth reaking havoc in Vietnam. It makes me thankful that we humans have a finite life expectancy.

After we'd hung up, I sat wondering what Iraq must look like through her eyes and if such images would come to constitute the temporal benchmarks of her young adulthood. Having lived on the planet for fifty five years hasn't made me smart but it has allowed me to notice when the same sorry things come around again and again. Perhaps the hardest to get my mind around is our governments periodic inclination to ship our precious children off to die for nothing. I'm not a pacifest. I can envision a just war, in fact my father and my uncles fought one. But whats happened in my time is different. Those leaders who take us to war for their own murky reasons don't believe it's worth their own childrens lives. Only one, one in 600 members of the United States Congress and Executive Branch has a child serving in Iraq .Thats right, nearly 2000 and counting American kids killed in Iraq for nothing more than the oppurtunistic and transient caprice of fools. I would like as much as the next person to pretend it was otherwise, to pretend these kids died for something necessary and noble,mostly because it breaks my heart to think of their parents. They must have to desperately cling to illusion or go mad. The fool of the moment's war doesn't appear to be going well and there's some suggestion that the shortage of fodder could necessitate a resumption of the draft. Should such a thing happen it's my intention to grab up a fistfull of those high limit, unsolicited credit cards that appear so often in my mailbox and drive as many young adults as are interested to a saner country. And, should my child in his/her youthful naivate be hoodwinked by the call to be all she can be I'll lock her in the basement until the madness passes. Janey is a very sweet, compassionate child. They are always the vulnerable ones. I wondered what kind of discount I could get if I went ahead and booked her a flight to Iraq thirty years in advance.

Vietnam, as I mentioned earlier, got me to thinking about how

different human lives can be. How for no reason other than the

fortuitous, or not so fortuitous, circumstances of your birth

you draw an easy life or a hard one. The experience has helped

me place my little bucket of woes( over which I have whined,

ad nauseam) in some much needed perspective. As anyone who knows

me well can readily attest, I've done nothing of note to warrant

my privileged perch on this porch. The truth is that if talent

and grit were the determinants of good fortune, Tan would be here

on the porch and I'd be trying to flag down a Saigon cyclo with

my phantom limb. If virtue were the determinant, Quan would be

courting a pretty Island girl and I'd be trying to convince an

aging Danang Mama-san that I was only on this bike cause my Honda

was in the shop. If kindness were the determinant, my anonymous

little ferry helper would be excelling at the Island school and

Donald Rumsfeld would be peddling chicklets on a ferryboat somewhere

in the middle of nowhere. Again, I must confess that any guilt

I feel regarding my random good fortune is far overshadowed by

my relief. I really wonder how I would have fared if the roll

of the dice had saddled me with a difficult life.