Child's Play

Child's Play

Boston, October 1997

by Matt Wolf

When she stars in the newly revised Diary Of Anne Frank this month, Natalie

Portman will be tackling material that is very close to home.

"I really think of acting more as my hobby," says Natalie Portman, who has

turned an afterschool activity into the sort of spiraling career to make

thespians of any age beet red with envy. Sixteen this past June, Portman has

become a critics' darling on screen, starting with her debut (at age 12) as the

wily, none-too-waiflike Mathilda alongside Jean Reno in The Professional.

Films followed--for Woody Allen (Everyone Says I Love You), Michael Mann (Heat),

and Tim Burton (Mars Attacks!). Ted Demme's Beautiful Girls remains her plum

credit to date, culminating in her casting as mother to Luke and Leia in the

prequel trilogy to Star Wars, the first of which found her busily filming in

England, Italy, and Africa all summer.

The Star Wars franchise guarantees that the high school honors student who runs

track and has just read Salinger's Franny and Zooey need never work again: her

commitment to the second and third films takes her through the year 2000 and

sets her up financially for life. But there's a separate reason for excitement

as the young actress shifts position on a sofa in the Dorchester Hotel, in

London, devouring the peculiar local interpretation of a sunny-side-up egg.

(Seated next to her is Portman's L.A. publicist, while father Avner has his

breakfast a table or two away.) This fall, she makes her Broadway debut as the

above-the-title star of The Diary of Anne Frank, playing the doomed heroine who

has long embodied the invincible human spirit as it was being assaulted by the

Holocaust. Directed by James Lapine, the $1.6 million revival of the 1955

Pulitzer Prizewinner opens the Colonial Theater's fall season, and will run from

October 28 to November 16. Broadway comes next, starting November 21.

The Star Wars franchise guarantees that the high school honors student who runs

track and has just read Salinger's Franny and Zooey need never work again: her

commitment to the second and third films takes her through the year 2000 and

sets her up financially for life. But there's a separate reason for excitement

as the young actress shifts position on a sofa in the Dorchester Hotel, in

London, devouring the peculiar local interpretation of a sunny-side-up egg.

(Seated next to her is Portman's L.A. publicist, while father Avner has his

breakfast a table or two away.) This fall, she makes her Broadway debut as the

above-the-title star of The Diary of Anne Frank, playing the doomed heroine who

has long embodied the invincible human spirit as it was being assaulted by the

Holocaust. Directed by James Lapine, the $1.6 million revival of the 1955

Pulitzer Prizewinner opens the Colonial Theater's fall season, and will run from

October 28 to November 16. Broadway comes next, starting November 21.

"What we're after and what James is after really is a fresh look," says

coproducer (and Colonial Theater president) Jon B. Platt, calling the show "a

perfect fit" for Boston. "Boston loves straight plays, in particular something

that's intellectual and thought-provoking, being the university city that it

is."

And lest the choice of play--however worthy and awarded in its day (it took the

Tony over Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Bus Stop)--seem rather shopworn, Platt

points out that playwright Wendy Kesselman's revised version of the Frances

Goodrich/Albert Hackett original incorporates fresh materials from the 1995

"definitive edition" of the diaries. The result, says Platt, presents Anne as

"more of a complete teenager than a sweet goody two-shoes. She was a teenager

with all of a teenager's mood swings, a fleshed-out kid."

That view of Anne tallies with Portman herself, who seems refreshingly real when

she could be a child-actor-turned-media-monster in the manner of all too many

young guns (they know who they are) whose celebrity has proceeded to plummet

around them. "I was mostly impressed with her personally," director Lapine says,

recalling initial impressions of a star whom he warmed to in the flesh rather

than on the screen. ("I'm not a big movie kinda guy, though I obviously went out

and looked at things she had done.")

"Natalie's a really bright kid, and she also has terrific parents," adds Lapine,

who remains best known for his collaborations with Stephen Sondheim on Passion,

Into the Woods, and Sunday in the Park with George. "She was very passionate

about the subject, and that kind of passion is so contagious. Hearing her read

the play, her natural instincts immediately made me perk up." Broadway producer

David Stone, who initiated the project, says of the preliminary reading,

"Natalie was so magnificent that not only was she crying during the last scene,

but so were the other actors; their mouths were agape at this girl."

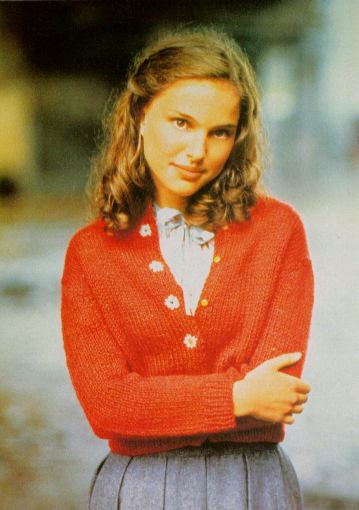

Dressed in jeans and a gray top, hair pulled back in a ponytail to reveal skin

that seems to shimmer, Portman professes an attachment to Anne that dates back

some years. "It was one of my dad's favorite books growing up," she says of her

father, a first-generation Israeli who now practices medicine near their home on

Long Island, "and he'd been pressuring me to read it. I never really wanted to

because I imagined it as this big, like depressing thing because I knew the gist

of it. I read it while filming The Professional in Paris and just fell in love

with it because it's a funny book. I mean, obviously it's sad and you know where

it's going but when you read it, you start laughing."

The 1995 version, says Portman, "has pages about how the boys like her and her

flirting techniques: she's very coy with them and demure; it's hilarious. She

has seven pages describing every single person in her class--who's annoying,

who's stupid, who's nice." The point, she adds, is that "it's a real diary. Anne

doesn't shy away from showing that she cares about the way she looks and how

self-centered she is. Because it's her diary, she doesn't think anyone's going

to read it; it's really honest."

Portman visited the Anne Frank house in Amsterdam several years back and was

planning a return trip in early September before leaving Europe to start

rehearsals for the play. "It's amazing," she says of the attic. "You walk in,

and it's, like, apartment-size, [whereas] when you're reading the book, you

imagine it to be a closet. For two years, there were nine people living there. I

mean, if I get into a fight with one of my parents, I just have to get out; I

have to, like, run outside. I can't imagine what it would be like having to sit

there and not be able to go anywhere, and also not to see daylight--that's the

scariest thing."

The story finds echoes in Portman's own background that lift the revival beyond

the realm of just another project. "Her father said, 'This is very important to

us as a family; we would turn down movies for her to do this,'" recalls Stone,

the show's producer. And that is confirmed by the Jerusalem-born actress, who

came to the United States with her parents (her mother is American) when she was

three. Not only was the Star Wars filming rearranged to enable Portman to finish

in time for the play, but the actress wanted to honor her own family's losses at

the hands of the Nazis: one of her father's uncles was murdered in the street,

while her paternal great-grandparents were killed at Auschwitz. "So I mean, it's

very, very close to us," she says of Anne Frank's story, adding softly, "I can't

imagine not knowing your grandparents."

And yet, Portman insists that the role be invested with hopefulness, not

despair. "You just need to play it as it is in life, how it was in life. There

was fear and dread every single day in that hiding place that they would be

caught eventually. But I think the human mind always turns to hope even though

there is that dread. Anne Frank was put in the worst situation possible and she,

like, saw good out of it; she kept her innocence and purity throughout that

whole time."

Innocence and purity are qualities one might assume to be slipping away from

Portman fast, given the name she has created for herself in a handful of films.

But one feels that her commitment to theater typifies a willingness to take

risks if the work is right. "I think a lot of young actors are scared to

dedicate so much time to theater," says the actress, who is contracted to the

play for nine months, rehearsals included. "It's scary for a lot of young actors,

especially one who's rising, to commit so many months to a show when they could

have been doing three films during that time. What if there's something I'm

dying to do in March? But I love this enough, and I'm excited enough, that I'm

willing to give up whatever comes up."

As it happens, it's a little-known fact of Portman's resume that she made her

professional debut not on screen but on stage, as understudy to two roles in the

1992-93 Off Broadway musical Ruthless. (It closed three weeks after she joined,

at which point she was plucked for The Professional.) "I was, like, 11 and just

thought it was this game," she says, round eyes smiling at the memory. "I kept

laughing on stage because I was having so much fun with this other girl: She

would cross her eyes at me on stage, and I'd start laughing, and people would be

like, Natalie, you're not supposed to laugh on stage." Discipline was learned

over three summers at theater camp, where roles included Dream Laurey in

Oklahoma! and Hermia in A Midsummer Night's Dream. The latter, she says, "is a

good one to do, because it's the easiest of the Shakespeares."

The stakes, of course, are far more serious now, as proved by the vocal coach

hired to work with Portman on enunciation, projection, and other issues that

rarely apply to the screen. "I've never really had the experience of doing the

same thing for nights and nights and nights," she says of a regime that

nevertheless sounds preferable to the 15-hour days demanded by George Lucas

since June 20, often in 140-degree Tunisian heat. "You get to be a lot more

expressive on stage; you don't have to worry as much about keeping it small.

Also, it will probably be better: when I do a movie, the night before I'm never

really perfect with my lines. When you do a show, you get to the point where you

have the lines down so well that it becomes, like, habit; you can concentrate on

other things."

And what of that other Natalie Portman, the effervescent high school junior who

goes gooey at the mention of Ben Kingsley ("he's so cute") and wants to study

photography and has 130 pages of AP history reading to wade through (and SATs to

worry about) at her Long Island public school? "It's really weird because I just

remember when I was, like, in kindergarten, if you were in high school even if

you were a freshman, you were old: you were almost an adult, married with kids."

Now contemplating college ("I want to go to school in Boston really badly

because it's such a great college town; it's THE college town"), she's having an

early-life crisis. "It's like, college, that's old, and now I'm an upperclassman

in high school, and I'm just like, Oh my God, I still don't feel like the image

that I had."

She puts it another way: "I lived for the Archie cartoons, and they seemed so

grown-up, and that was always my image of high-schoolers. I'm in my third year

of high school and I'm like, Oh my God, I'm such a baby." A "baby," that is,

with clout and intelligence and enthusiasm to burn. And as of The Diary of Anne

Frank, Boston's newest Broadway baby.

The Star Wars franchise guarantees that the high school honors student who runs

track and has just read Salinger's Franny and Zooey need never work again: her

commitment to the second and third films takes her through the year 2000 and

sets her up financially for life. But there's a separate reason for excitement

as the young actress shifts position on a sofa in the Dorchester Hotel, in

London, devouring the peculiar local interpretation of a sunny-side-up egg.

(Seated next to her is Portman's L.A. publicist, while father Avner has his

breakfast a table or two away.) This fall, she makes her Broadway debut as the

above-the-title star of The Diary of Anne Frank, playing the doomed heroine who

has long embodied the invincible human spirit as it was being assaulted by the

Holocaust. Directed by James Lapine, the $1.6 million revival of the 1955

Pulitzer Prizewinner opens the Colonial Theater's fall season, and will run from

October 28 to November 16. Broadway comes next, starting November 21.

The Star Wars franchise guarantees that the high school honors student who runs

track and has just read Salinger's Franny and Zooey need never work again: her

commitment to the second and third films takes her through the year 2000 and

sets her up financially for life. But there's a separate reason for excitement

as the young actress shifts position on a sofa in the Dorchester Hotel, in

London, devouring the peculiar local interpretation of a sunny-side-up egg.

(Seated next to her is Portman's L.A. publicist, while father Avner has his

breakfast a table or two away.) This fall, she makes her Broadway debut as the

above-the-title star of The Diary of Anne Frank, playing the doomed heroine who

has long embodied the invincible human spirit as it was being assaulted by the

Holocaust. Directed by James Lapine, the $1.6 million revival of the 1955

Pulitzer Prizewinner opens the Colonial Theater's fall season, and will run from

October 28 to November 16. Broadway comes next, starting November 21.

Child's Play

Child's Play