* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Victim Souls Newsletter

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Num. 10 April 1, 2022

= = = = = = = = = = = = =

Charity + Immolation

Through Mary and with Mary

The Roman Catholic Apostolic Church will Triumph

Under the Cross of Christ

Editorial

Divine Puzzles

“It is the lesson of the book of Job that man is most comforted by paradoxes. Here is the very darkest and strangest of the paradoxes; and it is by all human testimony the most reassuring. I need not suggest what high and strange history awaited this paradox of the best man in the worst fortune.” – ChestertonParables and Questions

One reason Christ taught so much by using parables, is that they are similar to riddles and to puzzles: a parable is something that has to be solved, it is something that makes you think. One of the best ways of teaching a subject is to ask the pupil a question that will make him think. Christ used this way of teaching, and God himself used it: Job asked him questions and he replied, not with answers but with questions and enigmas.

Seeking Answers

“And Eliu the son of Barachel the Buzite was angry against Job, because he said he was just before God. And he was angry with his friends, because they had not found a reasonable answer, but only had condemned Job. … Then he answered and said: Now thou hast said in my hearing, and I have heard the voice of thy words: I am clean, and without sin, I am unspotted, and there is no iniquity in me. Because he hath found complaints against me, therefore he hath counted me for his enemy. … Now this is the thing in which thou art not justified. I will answer thee, that God is greater than man.”

Eliu proceeded to give answers, but in modern language we would not call them answers, but rather comparisons, observations and enigmas. Finally God himself answered, not with answers in the current meaning of the word, but in questions and comparisons.

“Wilt thou give strength to the horse, or clothe his neck with neighing? Wilt thou lift him up like the locusts? The glory of his nostrils is terror. He breaketh up the earth with his hoof; he pranceth boldly; he goeth forward to meet armed men. He despiseth fear; he turneth not his back to the sword. Above him shall the quiver rattle, the spear and shield shall glitter. Chasing and raging he swalloweth the ground; neither doth he make account when the noise of the trumpet soundeth. When he heareth the trumpet he saith: Ha, ha. He smelleth the battle afar off, the encouraging of the captains, and the shouting of the army. Doth the hawk wax feathered by thy wisdom, spreading her wings to the south? Will the eagle mount up at thy command; and make her nest in high places? She abideth among the rocks, and dwelleth among cragged flints, and stony hills, where there is no access. From thence she looketh for the prey, and her eyes behold afar off. Her young ones shall suck up blood: and wheresover the carcass shall be, she is immediately there.”

Who has known the mind of the Lord?

If we cannot understand about horses and eagles, we can understand even less about God: His judgments are incomprehensible, and his ways unsearchable. (Rom. 11, 33)

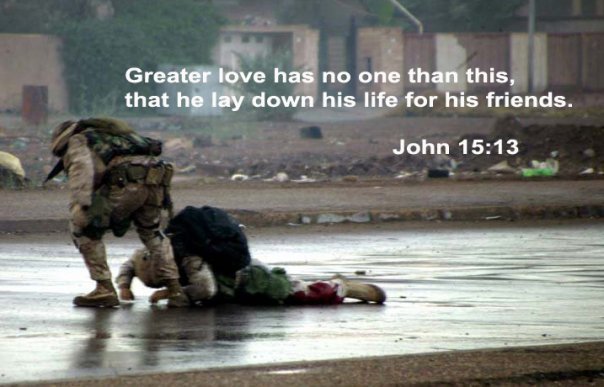

The Best Man in the Worst Fortune

To offer oneself as a victim is to do something similar to what Christ did: it is to deliberately offer oneself to affliction, illness, misery, abandonment, desolation, and trial. Such an offering might seem stupidity in the eyes of those who do not understand. If we saw our loved ones in danger of destruction, the best way of rescuing them, would be to do something similar to what Christ did. Christ did not save souls by miracles, he did not save them by teaching. He saved them in another way. The best way of acting is to do something similar to what he did. To be treated like Job may seem painful and humiliating, but in the end it will produce a happiness that will last forever, a never-ending triumph of glory and of joy.

“Because thou wast forsaken and hated, and there was none that passed through thee, I will make thee to be an everlasting glory, a joy unto generation and generation.” -- Isaiah 60

May it be for the glory of God

“All those who yield themselves to My way of the cross and suffering, will be blessed for all eternity.” -- Our Lord to Maria Concepcion: April 23, 1969

= = = = = = = = =

A Book That Changed the World

On Nov. 14, 1973, Our4 Lord said to Maria Concepcion (the Portavoz): "With respect to the life of perfection, it is just as you have grasped it this morning. Let people be guided by the book written by my very beloved son, Thomas a Kempis. He entitled his writings 'The Imitation of Christ,' by an order that I gave him, because he wrote these marvelous pages by the light of my spirit."

The Imitation of Christ was an early influence on the spirituality of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, who used it in her prayer life, distilled its message and used it in her own writings which then influenced Catholic spirituality as a whole. Thérèse was so attached to the book, and read it so many times, that she could quote passages from it from memory in her teens.

The Imitation of Christ, by Thomas à Kempis, is a Christian devotional book first composed in Medieval Latin as De Imitatione Christi (1418–1427). The devotional text is divided into four books of detailed spiritual instructions: (i) "Helpful Counsels of the Spiritual Life", (ii) "Directives for the Interior Life", (iii) "On Interior Consolation", and (iv) "On the Blessed Sacrament".

The book received an enthusiastic response from the very early days, as characterized by the statement of George Pirkhamer, the prior of Nuremberg, regarding the 1494 edition: "Nothing more holy, nothing more honorable, nothing more religious, nothing in fine more profitable for the Christian commonwealth can you ever do, than to make known these works of Thomas à Kempis."

In Book Two, Kempis writes that we must not attribute any good to ourselves but attribute everything to God. Kempis asks us to be grateful for "every little gift" and we will be worthy to receive greater ones, to consider the least gift as great and the most common as something special. Kempis writes that if we consider the dignity of the giver, no gift will seem unimportant or small (Chap. 10). In the last chapter, "The Royal Road of the Cross", Kempis writes that if we carry the cross willingly, it will lead us to our desired goal, but on the other hand if we carry our cross grudgingly, then we turn it into a heavy burden, and if we should throw off one cross, we will surely find another, which is perhaps heavier. Kempis writes that by ourselves we cannot bear the cross, but if we put our trust in the Lord, He will send us strength from heaven (Chap. 12). ---- (Read More Here) --

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

It Happened in Dublin many Years Ago

A winter's night had already thrown its black pall over the quays of Dublin when an urgent ringing of the presbytery door bell of one of the city parishes brought its aging pastor quickly to his feet.

It was so dark that he could scarcely distinguish the form of a woman on the doorstep. She spoke rapidly, as if anxious to be gone.

"A poor man," she said, "was dying very far down, beyond the great jetty of the North Wall. A priest was needed. There was no time to lose." And, having delivered her message, she sped away into the night.

"I will go myself," murmured the old priest, peering after the retreating figure.

There were no buses in those days, and the tram cars did not go along the quays, so he set out on foot.

It was very dark and he seemed to be walking a long time but he was heedless of fatigue as he clasped the Blessed Sacrament to his heart with one hand and carried the Holy Oils in the other.

His sole guide was the lighthouse flashing every two seconds across the bay.

The tide rose high on either side of the jetty on which he walked, and it was the sound of the waves rather than anything he could see which led him at last to a group of fishermen's cottages.

Instinctively, he stopped at one of them and pushed open the little door. There was no light and no sound broke the silence.

He entered but could see no one.

"Who will lead me to the sick man?" he asked himself anxiously.

He paused to listen. All was quiet.

Then his eyes, grown accustomed to the gloom, perceived a little staircase.

As he placed his foot on the first rickety step, a feeble voice fell upon his ear. But what was he saying so plaintively?

Holy Mary . . . Mother of God . . . pray for us . . . poor sinners … now . . . and at the hour of death… "Holy Mary . . . "

And ceaselessly the weak voice repeated again and again always the second part of the Hail Mary.

Gently the priest opened the door of the little room.

On a miserable pallet lay a poor man dying. He was all alone. "My friend, you sent for me?" began the priest.

"No, Father, I sent for no one!"

"I see that you love the Blessed Virgin. You are praying to her."

"I do not know who the Blessed Virgin is."

"Well, at least you pray to God."

"Never heard of Him."

The priest was puzzled. Who had come for him?

The man before him was obviously not hostile towards priests, but of God he knew nothing!

"My friend," he asked, "why do you repeat unceasingly 'Holy Mary Mother

of God . . .?"

"Ah!' replied the sick man, "when I am in great pain I say those words and they bring me relief."

And then he told the priest this touching story:

"I was a sailor, and oftentimes our ship was anchored off the west coast of Ireland. Those of us who wished got leave to spend the nights ashore in lodgings with the natives. I am not Irish but I liked those

people.

"In the cottage where I used to stay, the family gathered every night for prayers. The Mother said some words alone which I cannot recall, and all the others answered:

" 'Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us, poor sinners, now and at the hour of our death.'

"I have never forgotten those words and it does me good to say them."

The priest was deeply moved.

He remained all night with the sick man, talking to him of God, of the Blessed Virgin and of that other life which he was so soon to enter.

Here was a soul in all its freshness eager to drink in the eternal truths, a laborer of the eleventh hour indeed, and that Our Lady herself had gone out to seek . . .

At dawn the priest baptized him. He then gave him his first Holy Communion and the Sacrament of Extreme Unction.

When morning had come the priest had to leave.

"My friend," he said, "I must leave you.

. . . I am going to say Mass for you. . . . and I will return.

As he left the house he was deep in thought. Who, but who had come for him? He was certain someone had come, but who?

As if in answer to his thought a poorly clad woman appeared at the door

of one of the cottages. He spoke to her.

"That poor man up there is very ill," he said. "He will not last much longer." She shook her head, then added suddenly:"It was I who went for you. I do not belong to your religion. I am a Protestant, but when I heard Mr. . . . . . .always saying the Catholic prayer, I said to myself, 'I really must go and fetch

one of his ministers to him before he dies," so I went for you."

Trying to hide his emotion the priest thanked her for her charitable action and hastened away to offer the Holy Sacrifice.

"Here," he pondered, "is a poor unfortunate who repeated the Ave Maria without even knowing what he was saying, yet the Blessed Virgin heard his request!" 'Pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death!' . . .

She came, most certainly, at the hour of his death, this good and holy Mother!

"How far-reaching can be the effects of the Family Rosary said at nightfall in a Connemara cottage!"

------------------

The Revelations of Saint Gertrude

Part I

Written by Herself

Chapter 4

Of the stigmatas imprinted in the heart of Gertrude,

and her exercises in honour of the Five Wounds

I believe it was during the winter of the first or second year when I began to receive these favours that I found the following prayer in a book of devotions:

"O Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, grant that I may aspire towards Thee with my whole heart, with full desire and with thirsty soul, seeking only Thy sweetness and Thy delights, so that my whole mind and all that is within me may most ardently sigh to Thee, who art our true Beatitude. O most merciful Lord, engrave Thy wounds upon my heart with Thy most precious Blood, that I may read in them both Thy grief and thy love, and that the memory of Thy Wounds may ever remain in my inmost heart, to excite my compassion for Thy sufferings and to increase in me Thy love. Grant me also to despise all creatures, and that my heart may delight in Thee alone. Amen."

Having learned this prayer with great satisfaction, I repeated it frequently and Thou, who despisest not the prayer of the humble, heard my petitions. Soon after, during the same winter, being in the refectory after Vespers, for collation, I was seated near a person to whom I had made known my secret. I relate these things for the benefit of those who may read what I write, because I have often perceived that the fervour of my devotion is increased by this kind of communication. I know not for certain, O Lord my God, whether it was Thy Spirit, or perhaps human affection, made me act thus, although I have heard from those experienced in such matters that it is always better to reveal these secrets --not indifferently to all but chiefly to those who are not only our friends, but whom we are bound to reverence. As I am doubtful, as I have said, I commit all to Thy faithful Providence, whose spirit is sweeter than honey. If this fervour arose from any human affection, I am even more bound to have a profound gratitude for it, since Thou hast deigned to unite the mire of my vileness to the precious gold of Thy charity, that so the precious stones of Thy grace might be encased in me.

Being seated in the refectory, as I said before, I thought attentively on these things, when I perceived that the grace which I had so long asked by the aforesaid prayer was granted to me, unworthy though I am. I perceived in spirit that Thou hadst imprinted in the depth of my heart the adorable marks of Thy sacred wounds, even as they are on Thy Body, that Thou hadst cured my soul, in imprinting these Wounds on it, and that, to satisfy its thirst, Thou hadst given it the precious beverage of Thy love.

My unworthiness had not yet exhausted the abyss of Thy mercy. I received from Thine overflowing liberality this remarkable gift --that each time during the day in which I endeavoured to apply myself in spirit to those adorable Wounds, saying five verses of the Psalm Benedic, anima mea, Domino (Ps. cii.), I never failed to receive some new favour. At the first verse, "Bless the Lord, O my soul," I deposited all the rust of my sins and my voluptuousness at the Wounds of Thy blessed Feet. At the second verse, "Bless the Lord, and never forget all He hath done for thee," I washed away all the stains of carnal and perishable pleasures in the sweet bath of Blood and Water which Thou didst pour forth for me. At the third verse, "Who forgiveth all thine iniquities," I reposed my spirit in the Wound of Thy Left Hand, even as the dove makes its nest in the crevice of the rock. At the fourth verse, "Who redeemeth thy life from destruction," I approached Thy Right Hand and took from thence all that I needed for my perfection in virtue. Being thus magnificently adorned, I passed to the fifth verse, "Who satisfieth thy desire with good things," that I might be purified from all the defilement of sin and have the indigence of my wants supplied, so that I might become worthy of Thy presence, though of myself I am utterly unworthy, and might merit the joy of Thy chaste embraces.

I declare also that thou hast freely granted my other petition, namely, that I might read Thy grief and Thy love together. But, alas! this did not continue long, although I cannot accuse Thee of having withdrawn it from me. I complain of having lost it myself by my own negligence. This Thine excessive goodness and infinite mercy has hidden from itself and has procured to me, without any merit on my part, the greatest of Thy gifts --the impression of Thy Wounds, for which be praise, honour, glory, dominion and thanksgiving to Thee for endless ages!

Chapter 5. Of the Wound of Divine Love, and of the manner of bathing, anointing and binding it up. (To be continued)

Introduction to

THE BOOK OF JOB

"Man is most comforted by paradoxes."

by G.K. Chesterton

The book of Job is among the other Old Testament books both a philosophical riddle and a historical riddle. It is the philosophical riddle that concerns us in such an introduction as this; so we may dismiss first the few words of general explanation or warning which should be said about the historical aspect. Controversy has long raged about which parts of this epic belong to its original scheme and which are interpolations of considerably later date. The doctors disagree, as it is the business of doctors to do; but upon the whole the trend of investigation has always been in the direction of maintaining that the parts interpolated, if any, were the prose prologue and epilogue, and possibly the speech of the young man who comes in with an apology at the end. I do not profess to be competent to decide such questions.

But whatever decision the reader may come to concerning them, there is a general truth to be remembered in this connection. When you deal with any ancient artistic creation, do not suppose that it is anything against it that it grew gradually. The book of Job may have grown gradually just as Westminster Abbey grew gradually. But the people who made the old folk poetry, like the people who made Westminster Abbey, did not attach that importance to the actual date and the actual author, that importance which is entirely the creation of the almost insane individualism of modern times. We may put aside the case of Job, as one complicated with religious difficulties, and take any other, say the case of the Iliad. Many people have maintained the characteristic formula of modern skepticism, that Homer was not written by Homer, but by another person of the same name. Just in the same way many have maintained that Moses was not Moses but another person called Moses. But the thing really to be remembered in the matter of the Iliad is that if other people did interpolate the passages, the thing did not create the same sense of shock as would be created by such proceedings in these individualistic times. The creation of the tribal epic was to some extent regarded as a tribal work, like the building of the tribal temple. Believe then, if you will, that the prologue of Job and the epilogue and the speech of Elihu are things inserted after the original work was composed. But do not suppose that such insertions have that obvious and spurious character which would belong to any insertions in a modern, individualistic book.

Without going into questions of unity as understood by the scholars, we may say of the scholarly riddle that the book has unity in the sense that all great traditional creations have unity; in the sense that Canterbury Cathedral has unity. And the same is broadly true of what I have called the philosophical riddle. There is a real sense in which the book of Job stands apart from most of the books included in the canon of the Old Testament. But here again those are wrong who insist on the entire absence of unity. Those are wrong who maintain that the Old Testament is a mere loose library; that it has no consistency or aim. Whether the result was achieved by some supernal spiritual truth, or by a steady national tradition, or merely by an ingenious selection in aftertimes, the books of the Old Testament have a quite perceptible unity.

The central idea of the great part of the Old Testament may be called the idea of the loneliness of God. God is not the only chief character of the Old Testament; God is properly the only character in the Old Testament. Compared with His clearness of purpose, all the other wills are heavy and automatic, like those of animals; compared with His actuality, all the sons of flesh are shadows. Again and again the note is struck, "With whom hath He taken counsel?" (Isa. 40:14). "I have trodden the winepress alone, and of the peoples there was no man with me" (Isa. 63:3). All the patriarchs and prophets are merely His tools or weapons; for the Lord is a man of war. He uses Joshua like an axe or Moses like a measuring rod. For Him, Samson, is only a sword and Isaiah a trumpet. The saints of Christianity are supposed to be like God, to be, as it were, little statuettes of Him. The Old Testament hero is no more supposed to be of the same nature as God than a saw or a hammer is supposed to be of the same shape as the carpenter. This is the main key and characteristic of Hebrew scriptures as a whole. There are, indeed, in those scriptures innumerable instances of the sort of rugged humor, keen emotion, and powerful individuality which is never wanting in great primitive prose and poetry. Nevertheless the main characteristic remains: the sense not merely that God is stronger than man, not merely that God is more secret than man, but that He means more, that He knows better what He is doing, that compared with Him we have something of the vagueness, the unreason, and the vagrancy of the beasts that perish. "It is He that sitteth above the earth, and the inhabitants thereof are as grasshoppers" (Isa.40:22). We might almost put it thus. The book is so intent upon asserting the personality of God that it almost asserts the impersonality of man. Unless this gigantic cosmic brain has conceived a thing, that thing is insecure and void; man has not enough tenacity to ensure its continuance. "Except the Lord build the house, they labor in vain that build it. Except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain" (Ps. 127:1).

Everywhere else, then, the Old Testament positively rejoices in the obliteration of man in comparison with the divine purpose. The book of Job stands definitely alone because the book of Job definitely asks, "But what is the purpose of God? Is it worth the sacrifice even of our miserable humanity? Of course, it is easy enough to wipe out our own paltry wills for the sake of a will that is grander and kinder. But is it grander and kinder? Let God use His tools; let God break His tools. But what is He doing, and what are they being broken for?" It is because of this question that we have to attack as a philosophical riddle the riddle of the book of Job.

The present importance of the book of Job cannot be expressed adequately even by saying that it is the most interesting of ancient books. We may almost say of the book of Job that it is the most interesting of modern books. In truth, of course, neither of the two phrases covers the matter, because fundamental human religion and fundamental human irreligion are both at once old and new; philosophy is either eternal or it is not philosophy. The modern habit of saying "This is my opinion, but I may be wrong" is entirely irrational. If I say that it may be wrong, I say that is not my opinion. The modern habit of saying "Every man has a different philosophy; this is my philosophy and it suits me" - the habit of saying this is mere weak-mindedness. A cosmic philosophy is not constructed to fit a man; a cosmic philosophy is constructed to fit a cosmos. A man can no more possess a private religion, than he can possess a private sun and moon.

The first of the intellectual beauties of the book of Job is that it is all concerned with this desire to know the actuality; the desire to know what is, and not merely what seems. If moderns were writing the book, we should probably find that Job and his comforters got on quite well together by the simple operation of referring their differences to what is called the temperament, saying that the comforters were by nature "optimists" and Job by nature a "pessimist." And they would be quite comfortable, as people can often be, for some time at least, by agreeing to say what is obviously untrue. For if the word "pessimist" means anything at all, then emphatically Job is not a pessimist. His case alone is sufficient to refute the modern absurdity of referring everything to physical temperament. Job does not in any sense look at life in a gloomy way. If wishing to be happy and being quite ready to be happy constitutes an optimist, Job is an optimist. He is a perplexed optimist; he is an exasperated optimist; he is an outraged and insulted optimist. He wishes the universe to justify itself, not because he wishes it be caught out, but because he really wishes it be justified. He demands an explanation from God, but he does not do it at all in the spirit in which [John] Hampden might demand an explanation from Charles I. He does it in the spirit in which a wife might demand an explanation from her husband whom she really respected. He remonstrates with his Maker because he is proud of his Maker. He even speaks of the Almighty as his enemy, but he never doubts, at the back of his mind, that his enemy has some kind of a case which he does not understand. In a fine and famous blasphemy he says, "Oh, that mine adversary had written a book!" (31:35). It never really occurs to him that it could possibly be a bad book. He is anxious to be convinced, that is, he thinks that God could convince him. In short, we may say again that if the word optimist means anything (which I doubt), Job is an optimist. He shakes the pillars of the world and strikes insanely at the heavens; he lashes the stars, but it is not to silence them; it is to make them speak.

In the same way we may speak of the official optimists, the comforters of Job. Again, if the word pessimist means anything (which I doubt), the comforters of Job may be called pessimists rather than optimists. All that they really believe is not that God is good but that God is so strong that it is much more judicious to call Him good. It would be the exaggeration of censure to call them evolutionists; but they have something of the vital error of the evolutionary optimist. They will keep on saying that everything in the universe fits into everything else; as if there were anything comforting about a number of nasty things all fitting into each other. We shall see later how God in the great climax of the poem turns this particular argument altogether upside down.

When, at the end of the poem, God enters (somewhat abruptly), is struck the sudden and splendid note which makes the thing as great as it is. All the human beings through the story, and Job especially, have been asking questions of God. A more trivial poet would have made God enter in some sense or other in order to answer the questions. By a touch truly to be called inspired, when God enters, it is to ask more questions on His own account. In this drama of skepticism God Himself takes up the role of skeptic. He does what all the great voices defending religion have always done. He does, for instance, what Socrates did. He turns rationalism against itself. He seems to say that if it comes to asking questions, He can ask some questions which will fling down and flatten out all conceivable human questioners. The poet by an exquisite intuition has made God ironically accept a kind of controversial equality with His accusers. He is willing to regard it as if it were a fair intellectual duel: "Gird up now thy loins like man; for I will demand of thee, and answer thou me" (38:3). The everlasting adopts an enormous and sardonic humility. He is quite willing to be prosecuted. He only asks for the right which every prosecuted person possesses; he asks to be allowed to cross-examine the witness for the prosecution. And He carries yet further the corrections of the legal parallel. For the first question, essentially speaking, which He asks of Job is the question that any criminal accused by Job would be most entitled to ask. He asks Job who he is. And Job, being a man of candid intellect, takes a little time to consider, and comes to the conclusion that he does not know.

This is the first great fact to notice about the speech of God, which is the culmination of the inquiry. It represents all human skeptics routed by a higher skepticism. It is this method, used sometimes by supreme and sometimes by mediocre minds, that has ever since been the logical weapon of the true mystic. Socrates, as I have said, used it when he showed that if you only allowed him enough sophistry he could destroy all sophists. Jesus Christ used it when he reminded the Sadducees, who could not imagine the nature of marriage in heaven, that if it came to that, they had not really imagined the nature of marriage at all. In the break up of Christian theology in the eighteenth century, [Joseph] Butler used it, when he pointed out that rationalistic arguments could be used as much against vague religions as against doctrinal religion, as much against rationalist ethics as against Christian ethics. It is the root and reason of the fact that men who have religious faith have also philosophic doubt. These are the small streams of the delta; the book of Job is the first great cataract that creates the river. In dealing with the arrogant asserter of doubt, it is not the right method to tell him to stop doubting. It is rather the right method to tell him to go on doubting, to doubt a little more, to doubt every day newer and wilder things in the universe, until at last, by some strange enlightenment, he may begin to doubt himself.

This, I say, is the first fact touching the speech; the fine inspiration by which God comes in at the end, not to answer riddles, but to propound them. The other great fact which, taken together with this one, makes the whole work religious instead of merely philosophical is that other great surprise which makes Job suddenly satisfied with the mere presentation of something impenetrable. Verbally speaking the enigmas of the Lord seem darker and more desolate than the enigmas of Job; yet Job was comfortless before the speech of the Lord and is comforted after it. He has been told nothing, but he feels the terrible and tingling atmosphere of something which is too good to be told. The refusal of God to explain His design is itself a burning hint of His design. The riddles of God are more satisfying than the solutions of man.

Thirdly, of course, it is one of the splendid strokes that God rebukes alike the man who accused and the men who defended Him; that He knocks down pessimists and optimists with the same hammer. And it is in connection with the mechanical and supercilious comforters of Job that there occurs the still deeper and finer inversion of which I have spoken. The mechanical optimist endeavors to justify the universe avowedly upon the ground that it is a rational and consecutive pattern. He points out that the fine thing about the world is that it can all be explained. That is the one point, if I may put it so, on which God, in return, is explicit to the point of violence. God says, in effect, that if there is one fine thing about the world, as far as men are concerned, it is that it cannot be explained. He insists on the inexplicableness of everything. "Hath the rain a father?. . .Out of whose womb came the ice?" (38:28f). He goes farther, and insists on the positive and palpable unreason of things; "Hast thou sent the rain upon the desert where no man is, and upon the wilderness wherein there is no man?" (38:26). God will make man see things, if it is only against the black background of nonentity. God will make Job see a startling universe if He can only do it by making Job see an idiotic universe. To startle man, God becomes for an instant a blasphemer; one might almost say that God becomes for an instant an atheist. He unrolls before Job a long panorama of created things, the horse, the eagle, the raven, the wild ass, the peacock, the ostrich, the crocodile. He so describes each of them that it sounds like a monster walking in the sun. The whole is a sort of psalm or rhapsody of the sense of wonder. The maker of all things is astonished at the things he has Himself made.

This we may call the third point. Job puts forward a note of interrogation; God answers with a note of exclamation. Instead of proving to Job that it is an explicable world, He insists that it is a much stranger world than Job ever thought it was. Lastly, the poet has achieved in this speech, with that unconscious artistic accuracy found in so many of the simpler epics, another and much more delicate thing. Without once relaxing the rigid impenetrability of the Lord in His deliberate declaration, he has contrived to let fall here and there in the metaphors, in the parenthetical imagery, sudden and splendid suggestions that the secret of God is a bright and not a sad one - semi-accidental suggestions, like light seen for an instant through the crack of a closed door.

It would be difficult to praise too highly, in a purely poetical sense, the instinctive exactitude and ease with which these more optimistic insinuations are let fall in other connections, as if the Almighty Himself were scarcely aware that He was letting them out. For instance, there is that famous passage where the Lord, with devastating sarcasm, asks Job where he was when the foundations of the world were laid, and then (as if merely fixing a date) mentions the time when the sons of God shouted for joy (38:4-7). One cannot help feeling, even upon this meager information, that they must have had something to shout about. Or again, when God is speaking of snow and hail in the mere catalogue of the physical cosmos, he speaks of them as a treasury that He has laid up against the day of battle - a hint of some huge Armageddon in which evil shall be at last overthrown.

Nothing could be better, artistically speaking, than this optimism breaking though agnosticism like fiery gold round the edges of a black cloud. Those who look superficially at the barbaric origin of the epic may think it fanciful to read so much artistic significance into its casual similes or accidental phrases. But no one who is well acquainted with great examples of semi-barbaric poetry, as in The Song of Roland or the old ballads, will fall into this mistake. No one who knows what primitive poetry is can fail to realize that while its conscious form is simple, some of its finer effects are subtle. The Iliad contrives to express the idea that Hector and Sarpedon have a certain tone or tint of sad and chivalrous resignation, not bitter enough to be called pessimism and not jovial enough to be called optimism; Homer could never have said this in elaborate words. But somehow he contrives to say it in simple words. The Song of Roland contrives to express the idea that Christianity imposes upon its heroes a paradox; a paradox of great humility in the matter of their sins combined with great ferocity in the matter of their ideas. Of course The Song of Roland could not say this; but it conveys this. In the same way, the book of Job must be credited with many subtle effects which were in the author's soul without being, perhaps, in the author's mind. And of these by far the most important remains to be stated.

I do not know, and I doubt whether even scholars know, if the book of Job had a great effect or had any effect upon the after development of Jewish thought. But if it did have any effect it may have saved them from an enormous collapse and decay. Here in this book the question is really asked whether God invariably punishes vice with terrestrial punishment and rewards virtue with terrestrial prosperity. If the Jews had answered that question wrongly they might have lost all their after influence in human history. They might have sunk even down to the level of modern well-educated society. For when once people have begun to believe that prosperity is the reward of virtue, their next calamity is obvious. If prosperity is regarded as the reward of virtue it will be regarded as the symptom of virtue. Men will leave off the heavy task of making good men successful. The will adopt the easier task of making out successful men good. This, which has happened throughout modern commerce and journalism, is the ultimate Nemesis of the wicked optimism of the comforters of Job. If the Jews could be saved from it, the book of Job saved them.

The book of Job is chiefly remarkable, as I have insisted throughout, for the fact that it does not end in a way that is conventionally satisfactory. Job is not told that his misfortunes were due to his sins or a part of any plan for his improvement. But in the prologue we see Job tormented not because he was the worst of men, but because he was the best. It is the lesson of the whole work that man is most comforted by paradoxes. Here is the very darkest and strangest of the paradoxes; and it is by all human testimony the most reassuring. I need not suggest what high and strange history awaited this paradox of the best man in the worst fortune. I need not say that in the freest and most philosophical sense there is one Old Testament figure who is truly a type; or say what is prefigured in the wounds of Job.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

God needs our suffering, to be used by virtue of the Communion of Saints, to assist other souls in their redemption.

God sends the heaviest crosses to those He calls His own,

And the bitterest drops of the chalice are reserved for His friends alone.

But the blood red drops are precious, and the crosses are all gain,

For Joy is bought with Sacrifice, and the price of love is Pain.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

The Work of Atonement is the highest consecration that one can make, to surrender oneself to Jesus in doing His Divine Will.

Requirements to Become a Victim-Soul

• Daily Mass

• Monthly Confession

• Morning Offering

• Daily Rosary

• Own personal devotions

• Should wear Miraculous Medal, as well as a Brown Scapular. --

Benefits of Victimhood

• Victim-Souls never see Purgatory, they will see Heaven

• Special Graces from the Blessed Mother and Her Son

• Receive greater merits for prayers and Holy Masses

• You become the apple of the Father's eye, because you desire to imitate His Son

• Victim-Souls united with victimhood are holding back the great chastisement

• The purpose of victimhood is to release suffering souls from Purgatory, and to save sinners from the horror of eternal condemnation.

Consecration of the Legion of Victim Souls

LORD my God, you have asked everything of your little servant: take and receive everything, then. etc.

(See "Victimhood of Little Souls" in the list of free atonement booklets, for complete consecration.)

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

To unsubscribe, send message: "Remove my address from list."

= = = = = = = = = = = = = =

|