Glantz, David M. Barbarossa:

Hitler's Invasion of Russia 1941. Tempus Publishing Inc. Charleston. 2001.

Soviet Response.

Command and Control.

The staggering defeats the Red Army suffered during the initial three weeks

of war exacerbated the consternation that had seized Stalin and his satraps

when Hitler began Operation Barbarossa. Even though the Soviet leadership reacted

in wooden fashion, it did what was prudent and necessary under the circumstances.

Mobilization continued at a frantic pace, Stalin organized central command and

control organizations and organs and, in a steady stream of orders, Commissar

of Defence Timoshenko and Chief of the General Staff Zhukov demanded Red Army

forces implement the State Defence plan. Within only days of the German invasion,

this command troika ordered the Red Army's forward fronts, already savaged by

the brutally efficient German war machine, to strike back at their tormentors

and drive them from Russian soil. To see to it that they carried out the orders,

both Timoshenko and Zhukov personally visited the operating fronts.

Despite their bravado, however, these orders rang hollow, particularly to those

who were responsible for carrying them out since it was clear that they were

simply incapable of doing so. In vain, and at immense human and material cost,

front after front, army after army, corps after corps of the Red Army's first

strategic echelon attempted to do what the State Defence Plan required of them

and quickly and dramatically perished. Nevertheless, in late June and early

July, Stalin, Timoshenko and Zhukov hastily and stoically formed and deployed

forward the first of many groups of Stavka reserve armies. In succession throughout

July and August, these armies occupied row after row of reserve defensive positions

stretching eastward from the Dnepr river to the approaches to Moscow proper.1

While the Soviet regime responded rationally to the German invasion, it soon

recognized that the Wehrmacht and its Blitzkrieg tactics clearly outclassed

the Red Army. In fact, the attacking German forces destroyed the Soviet command

and control system, dismembered the cumbersome Red Army, disrupted Soviet mobilization

and threatened to smash the Soviet Union's military-industrial base. Given the

resulting devastation and havoc, the Soviet leadership realized that survival

required doing far more than issuing strident attack orders and raising and

fielding new armies. Therefore, Moscow began fundamentally altering its command

and control system and procedures, its military force structure and organization

and its military-industrial base, all during the first three weeks of the war.

While doing so, the Red Army temporarily abandoned many of its prewar doctrinal

concepts, making the first of many painful but effective adjustments to the

reality of modern war.

The first order of business was to establish a wartime national command structure

from the existing Peoples' Commissariat of Defence [Narodnyi komissariat

oborony -NKO] and Red Army General Staff [General'nyi shtab Krasnoi

Armii - GshKA], which could effectively control mobilization and direct

the war effort.2 Even though this structure's nomenclature and organization

changed frequently during the first six weeks, the changes had little practical

impact on the day-to-day conduct of the war. Stalin began the organization effort

on 23 June, when he activated the Stavka [headquarters] of the Main

Command [Stavka Glavnogo Kotnandovaniia - SGK], a war council that

was the 'highest organ of strategic leadership of the Armed Forces of the USSR'.

Chaired by Defence Commissar Timoshenko, the Stavka included a political component

consisting of Stalin and V.K. Molotov and a military component made up of G.K.

Zhukov, K.E. Voroshilov, S.M. Budenny, and N.G. Kuznetsov. After a bewildering

series of changes in name and membership, the council ultimately emerged on

8 August as the Stavka of the Supreme High Command (Stavka Verkhnogo Glavnokomandovaniia

- SVGK,), with Stalin as titular Supreme High Commander.3

Stalin exercised his full wartime powers as chairman of the State Defence Committee

[Gosudarstvennyi Komitet Oborony - GKO], a virtual war cabinet. Formed on 30

June 1941 by a joint order of the "Presidium ot the USSR's Supreme Soviet,

the Communist Party Central Committee and the Council of People's Commissars

(CNK), 'all power was concentrated' in this 'extraordinary highest state organ

in the wartime Soviet Union.'4 The committee's initial members were Stalin,

V.M. Molotov (deputy chairman), K.E. Voroshilov, L.P. Beriia, and G.M. Malenkov.5

The GKO directed the activities of all government departments and institutions

as a whole, including the Stavka and the General Staff, and directed and supported

all aspects of the war effort. In addition, each mem6er specialized on nutters

within the sphere of his own competency.6 GKO resolutions had the full strength

of law in wartime, and all state, party, economic, all-union and military organs

were responsible 'absolutely' for fulfilling its decisions and instructions.7

The Stavka worked under the specific direction of the Politburo of

the Communist Party Central Committee and the GKO. Its responsibilities included

evaluating political-military and strategic conditions, reaching strategic and

operational-strategic decisions, creating force groupings and coordinating the

operations of groups of fronts, fronts, field armies and partisan

forces. The Stavka directed the formation and training of strategic

reserves and material and technical support of the armed forces, and resolved

all questions related to military operations.

Subordinate to the Stavka was the Red Army General Staff, which the

Stavka relied upon to provide strategic direction for the war.8 The Stavka

reached all decisions regarding the preparation and conduct of military campaigns

and strategic operations after thorough discussions of proposals made by the

General Staff and appropriate front commanders. While doing so, it

discussed the proposals with leading military, state and Communist Party leaders

and with the heads of involved People's Commissariats. Throughout this process,

the Stavka directly supervised fronts, fleets, and long-range aviation,

assigned missions to them, approved operational plans and supported them with

necessary forces and weaponry. It also directed the partisan movement through

the Central Headquarters of the Partisan Movement. In practice, however, the

term Stavka came to be used loosely to describe Stalin, the Supreme

High Command, and the General Staff that served both. A separate Red Army Air

Force Command (Kommandnitishii VVS Krasnoi Armii) was also established

to sort out the wreckage of the Red Air Force.

Despite this frenetic establishment of command structure, neither Stalin nor

his chief military advisers exercised strong centralized control during the

first days of the war, primarily since the command communications system did

not function. Stalin himself appeared to withdraw from public view and even

from the day-to-day conduct of the war, perhaps in shock.9 Late on 22 June,

the day of invasion, Premier and Minister of Foreign Affairs Molotov made a

halting, plaintive radio address, announcing the German attack but apparently

still unwilling to believe that total war had begun. Not until 3 July did Stalin

himself address the nation, when he delivered a strong radio address calling

for guerrilla resistance and the destruction or evacuation of anything useful

to the invader. Already in this speech, Stalin began to stress Russian nationalism

instead of loyalty to the Soviet state, an emphasis that the regime continued

throughout the war.

Meanwhile, Stalin dispatched his principal military advisors, including Timoshenko,

Zhukov, Vasilevsky and Budenny, from the capital as soon as the war began in

a desperate attempt to learn what was happening and restore some degree of control

over the deteriorating situation. On 10 August Stalin restored some semblance

of stability to command and control by appointing Shaposhnikov to replace Zhukov

as Chief of the Red Army General Staff, while senior commanders who enjoyed

Stalin's trust acted as theatre commanders or trouble-shooters, changing location

frequently to .provide government-level emphasis to crisis areas.10

The cornerstone of Stalin's new rationalized command and control system for

the Reel Army were three theatre-level, muhi-front strategic commands termed

High Commands of Directions [Glavnye komandovaniia napravlenii], which

Stalin formed

on 10 July.11 These commands were designed to provide unity of control over

all fronts and other forces operating along a single strategic axis. Originally,

K.E. Voroshilov headed the Northwestern Direction, including the Northern and

Northwestern Fronts and the Baltic and Northern Fleets, Timoshenko the Western

Direction, including the Western Front, and Budenny the Southwestern Direction,

including the Southwestern and Southern Fronts and Black Sea Fleet. When Timoshenko

assumed direct control of the Western Front in late July, Lieutenant-General

V.D. Sokolovsky nominally became head of the Western Direction. The commissars

or 'Members of the Military Council' for the three direction commands were three

future leaders of the Communist Party, A.A. Zhdanov, N.A. Bulganin and N.S.

Khrushchev respectively. In practice, however, Stalin and the Stavka frequently

bypassed the three Direction Commands by issuing orders directly to subordinate

headquarters. This layer of command proved to be superfluous and ineffective

and was eliminated during 1942.

In the best Stalinist tradition, the initial defeats brought renewed authority

to the political commissars, who assumed co-equal status with force commanders

and chiefs of staff. While many career soldiers were released from prison to

help fight the invaders, others took their places in a general atmosphere of

suspicion.12 Pavlov was not the only commander to face summary execution. Many

soldiers who escaped from German encirclements returned to Soviet lines only

to find themselves disarmed, arrested and interrogated by NKVD 'rear security'

units looking for cowardice and sabotage. In addition, 95,000 civilian members

of the Communist Party and Communist Youth organization (KOMSOMOL) were mobilized

at the end of June; some of these went into specially formed shock units, while

others were expected to reinforce the dedication of the surviving Red Army units.

The renewed Communist Party influence and terror in the army was unnecessary,

since virtually all soldiers were doing their utmost without such threats. The

moving force behind this Party involvement was the sinister L.Z. Mekhlis, whom

Stalin appointed as Chief of the Red Army's Main Political Directorate on 23

June 1941. In addition, Mekhlis served as a deputy People's Commissar of Defence,

a position in which he continued his job as political watchdog over the Soviet

officer's corps.13 Voroshilov, Zhukov and most career military officers despised

Mekhlis for his role in the Great Purges and resisted his efforts to meddle

in the conduct of the war. Ultimately, Mekhlis himself fell victim to his own

system.

The Great Purges, which were still continuing when war began, had a lasting

impact on the Red Army's performance in the initial period of war, since many

of the initial Soviet defeats resulted directly from the surviving Soviet officer

corps' inexperience. Field commanders at every level occupied positions for

which they were unqualified, lacked the practical experience and confidence

necessary to adjust to changing tactical situations and tended to apply stereotypical

solutions, distributing their subordinate units according to textbook diagrams

without regard for the actual terrain. The results were predictable. Forces

that operated without regard to such principles of war as unity of command and

concentration and attacked and defended in stylized and predictable fashion

quickly fell victim to the more experienced Germans.14

Headquarters at every level lacked trained staff officers necessary to coordinate

manoeuvre, fire support and logistics. The border battles in the Ukraine were

typical, with field army headquarters proving incapable of coordinating simultaneous

attacks

by more than one mechanized corps and unable to direct the few available aircraft

to provide effective support to the ground units. There were exceptions, of

course, but the overall performance of the Red Army hierarchy was so poor that

it contributed to the confusion caused by the surprise attack. Small wonder

that both German and Western military observers concluded that the Red Army

was on the verge of final disintegration.

Soviet staffs also lacked effective communications to control their subordinates

and report the situation to their superiors. Once German infiltrators and air

strikes hamstrung the fixed telephone network, many headquarters were unable

to communicate at all. Even the military district headquarters, which upon mobilization

became front commands, were short of long-range radio equipment and skilled

radio operators. Existing Soviet codes were so cumbersome that commanders often

transmitted their messages 'in the clear,' providing ample tactical intelligence

for the German radio intercept units.

In other words, the Red Army had too many headquarters for the available trained

staff officers and communications. Moreover, the initial defeats caused the

average strength of divisions, corps, and field armies to decline so precipitously

that the remnants no longer justified the elaborate hierarchy of headquarters

left in command. This, plus a general shortage of specialized weapons such as

tanks and antitank weapons, suggested that the organizational structure of the

Red Army required a drastic simplification.

Reorganization.

The ensuing wholesale reorganization of the Red Army that took place through

the summer of 1941 was nothing more than a series of stopgap measures forced

on the Stavka by necessity: the unpleasant fact was that the Wehrmacht

had either smashed or was in the process of smashing the Red Army's prewar structure,

leaving the Stavka no choice but to reorganize the Red Army if it was

to survive at all. Despite this sad reality, the fact that the Stavka

was able to conceive of and execute so extensive a reorganization at a time

when the German advance placed them in a state of perpetual crisis-management

was a tribute to the wisdom of the senior Red Army leadership. As it surveyed

the wreckage that was its army, the Stavka decided to replace the complex

army structure with simpler and smaller organizations at every level of command:

a force that its inexperienced officers could command and control, and a force

that could survive. Hence, Stavka consciously formed obviously more

fragile and, hence, more vulnerable forces, all for the sake of officer education.

In short, the Stavka saved the Red Army by reorganizing it, all the

while abandoning temporarily any hopes of implementing its sophisticated prewar

operational and tactical concepts. At the same time, the Stavka also tacitly

accepted the immense casualties their new 'light' army suffered in the ensuing

year. The fact that the Stavka gradually rebuilt a 'heavier' Red Army in spring

1942 was indicative of the temporary nature of the 1941 reorganization.

Stavka Directive No. 01 (dated 15 July 1941) and associated instructions

began the reorganization and truncation process.15 The directive ordered Direction,

front and army commanders to eliminate the rifle corps link from armies because

they were 'too cumbersome, insufficiently mobile, awkward and unsuited for manoeuvre.'16

It created new, smaller field armies which the few experienced army commanders

and staffs could more effectively control. These consisted of five or six rifle

divisions, two or three tank brigades, one or two light cavalry divisions and

several attached Stavka reserve artillery regiments. The rifle divisions

were also simplified, giving up many of the specialized antitank, anti-aircraft,

armour and field artillery units included in peacetime division establishments.

Such equipment was in desperately short supply, and the new system centralized

all specialized assets so that the army commanders could allocate them to support

the most threatened subordinate units. In the process, the authorized strength

of a rifle division decreased from 14,500 to just under 11,000 men, and the

number of artillery pieces and trucks decreased by 24% and 64% respectively.17

The actual strength of most divisions was much lower and, as time passed, many

of these weakened units were re-designated as separate rifle brigades. During

the fall of 1941 and early 1942, the Stavka formed about 170 rifle brigades

in lieu of new rifle divisions. These demi-divisions of 4,400 men each consisted

of three rifle and various support battalions subordinate directly to brigade

headquarters and were significantly easier for inexperienced Soviet commanders

to control.

Directive No. 01 also abolished mechanized corps, which seemed particularly

superfluous given the current shortage of skilled commanders and modern tanks.

Most motorized rifle divisions in these corps were re-designated as the normal

rifle divisions that they in fact were. The surviving tank divisions were retained

on the books at a reduced authorization of 217 tanks each. Some of the original,

higher-numbered reserve tank divisions that had not yet seen combat were split

to produce more armoured units of this new pattern.18 Virtually all such tank

units were subordinated to rifle army commanders. In fact, tanks were so scarce

in the summer and fall of 1941 that tank brigades were the largest new armoured

organizations formed during this period. Some of these brigades had as few as

50 newly produced tanks, with minimal maintenance and other support.19 For the

moment, therefore, the Red Army had abandoned its previous concept of large

mechanized units, placing all the surviving tanks in an infantry-support role.

Associated directives also mandated expansion of cavalry units, creating 30

new light cavalry divisions of 3,447 horsemen each.20 Later in the year, this

total rose to 82 such divisions but, because of high losses, by late December

the divisions were integrated into the cavalry corps. Apparently Civil War-era

commanders like Budenny were attempting to recover the mobility of that era

without regard to the battlefield vulnerability of such horses. German accounts

tended to ridicule such units as hopeless anachronisms. Still, given the shortage

of transportation of all types, the Soviet commanders felt they had no choice.

During the winter of 1941-42, when all mechanized units were immobilized by

cold and snow, the horse cavalry divisions (and newly created ski battalions

and brigades) proved effective in the long-range, guerrilla warfare role that

Stalin and Budenny had envisaged.

At the same time as independent operations for mechanized forces were sacrificed,

so the Red Air Force abolished its Strategic Long-range Aviation command temporarily.

Tactical air units were reorganized into regiments of only 30, rather than 60,

aircraft.

Organization was easier to change than tactical judgement, however. Soviet commanders

from Stalin down displayed a strange mixture of astuteness and clumsiness well

into 1942. Most of the great changes in Soviet operational and tactical concepts

and practice did not occur until 1942-43, but, during the crisis of 1941, the

Stavka began the first steps in this process. Many of the instructions issued

at the time seem absurdly simple, underlining the inexperience of the commanders

to whom they were addressed. For example, on 28 July 1941, the Stavka issued

Directive No. 00549, entitled 'Concerning Measures to Regulate the Employment

of Artillery in the Defence.'21 The directive ordered commanders to form integrated

anti-tank regions along the most likely avenues of German mechanized advance

and forbade them from distributing their available artillery evenly across their

defensive front. In August the Stavka formally criticized commanders who had

established thinly spread defences lacking depth or antitank defences. While

creating such depth was easier said than done when so many units were short

of troops and guns, the basic emphasis on countering known German tactics was

a sound approach.

Whether attacking or defending, many Soviet officers tended to manoeuvre their

units like rigid blocks, making direct frontal assaults against the strongest

German concentrations. This was poor tactics at any time, but it was especially

foolhardy when the Red Army was so short-handed and under-equipped. The December

1941 Soviet counteroffensive at Moscow suffered from such frontal attacks, exasperating

Zhukov. Thus, on 9 December he issued a directive that forbid frontal assaults

and ordered commanders to seek open flanks in order to penetrate into the German

rear areas.22 Such tactics were entirely appropriate under the conditions of

December but would not necessarily have worked against the Germans during their

triumphant advance of June through October.

Force Generation.

The abolition of mechanized corps retroactively corrected a glaring error in

German intelligence estimates about the Red Army. Prior to the invasion, the

Germans had a fairly accurate assessment of the total strength of the active

Red Army, but they had almost no knowledge of the new mechanized corps and antitank

brigades. German intelligence analysts apparently believed that the Red Army

was still at the 1939 stage, when large mechanized units had been abandoned

in favor of an infantry support role. Prior to 22 June, the Germans had identified

only three of the sixteen mechanized corps in the forward military districts.23

The massed appearance of these mechanized units in the field against First Panzer

Group at the end of June was almost as great a surprise as the first encounters

with KV-1 and T-34 tanks.

Yet the greatest German intelligence error lay in under-estimating the Soviet

ability to reconstitute shattered units and form new forces from scratch. Given

the German expectation of a swift victory, their neglect of this Soviet capability

is perhaps understandable. In practice, however, the Red Army's ability to create

new divisions as fast as the Germans smashed existing ones was a principal cause

of the German failure in 1941.

For much of the 1920s and 1930s, the Red Army had emphasized the idea of cadre

and mobilization forces, formations that had very few active duty soldiers in

peacetime but would gain reservists and volunteers to become full-fledged combat

elements in wartime. As war approached in the late 1930s, the Red Army tended

to neglect this concept, gradually mobilizing most of its existing units to

full-time, active duty status. Still, prewar Soviet theory estimated that the

army would have to be completely replaced every four to eight months during

heavy combat. To satisfy this need, the 1938 Universal Military Service Law

extended the reserve service obligation to age 50 and created a network of schools

to train those reservists. By the time of the German invasion, the Soviet Union

had a pool of 14 million men with at least basic military training. The existence

of this pool of trained reservists gave the Red Army a depth and resiliency

that was largely invisible to German and other observers.

From the moment the war began, the Peoples' Commissariat of Defence began a

process that produced new groups or 'waves' of rifle armies over a period of

several months.24 At the outset of war, the General Staff's Organizational and

Mobilization Directorate was responsible for mobilization and force generation.

However, the wartime General Staff was too busy dealing with current operations

to deal effectively with the matter. Therefore, on 29 July the Stavka

removed the directorate from the General Staff and assigned it to the NKO, renaming

it the Main Directorate for the Formation and Manning of the Red Army [Glavnoe

upravlenie formirovaniia i ukomplektovaniia Krasnoi Armii - GUFUKA].25

Under NKO supervision, the military districts outside the actual war zone then

established a system for cloning existing active duty units to provide the cadres

that were filled up with reservists. The NKO summoned 5,300,000 reservists to

the colors by the end of June, with successive mobilizations later.26 In addition

to the 8 armies the NKO mobilized and deployed in late June, it raised 13 new

field armies in July, 14 in August, 3 in September, 5 in October, 9 in November

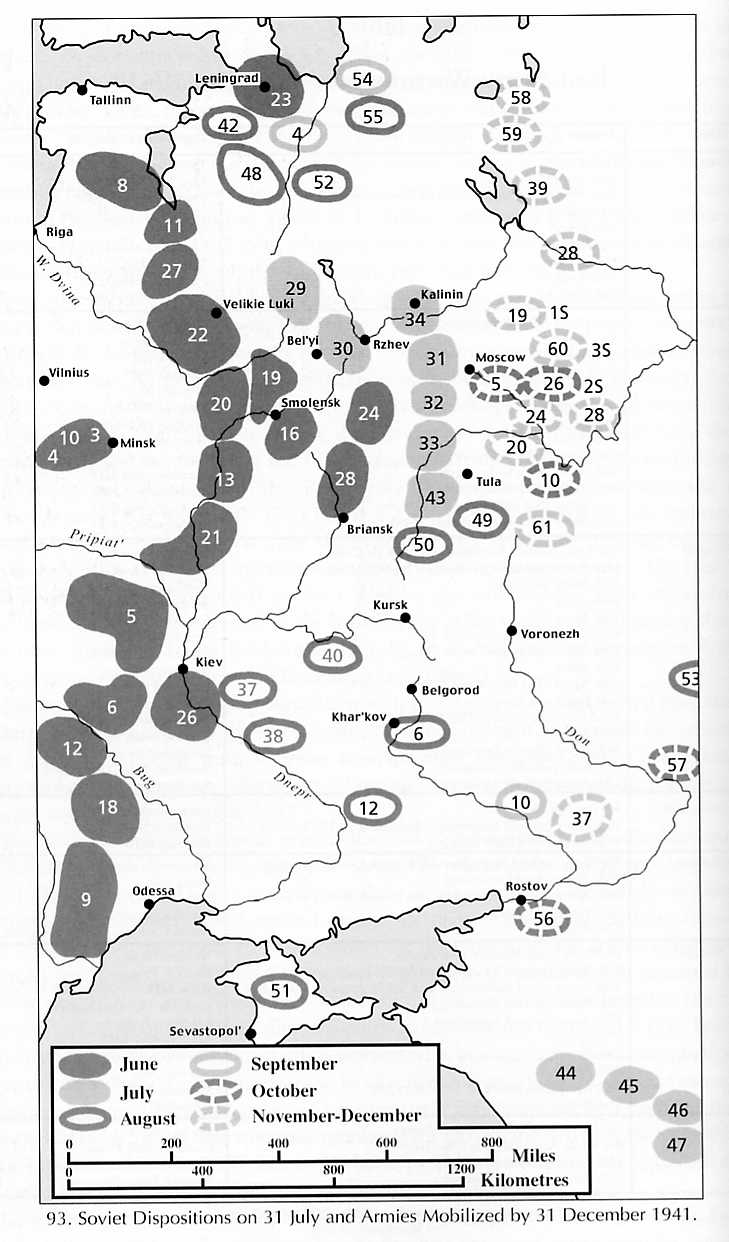

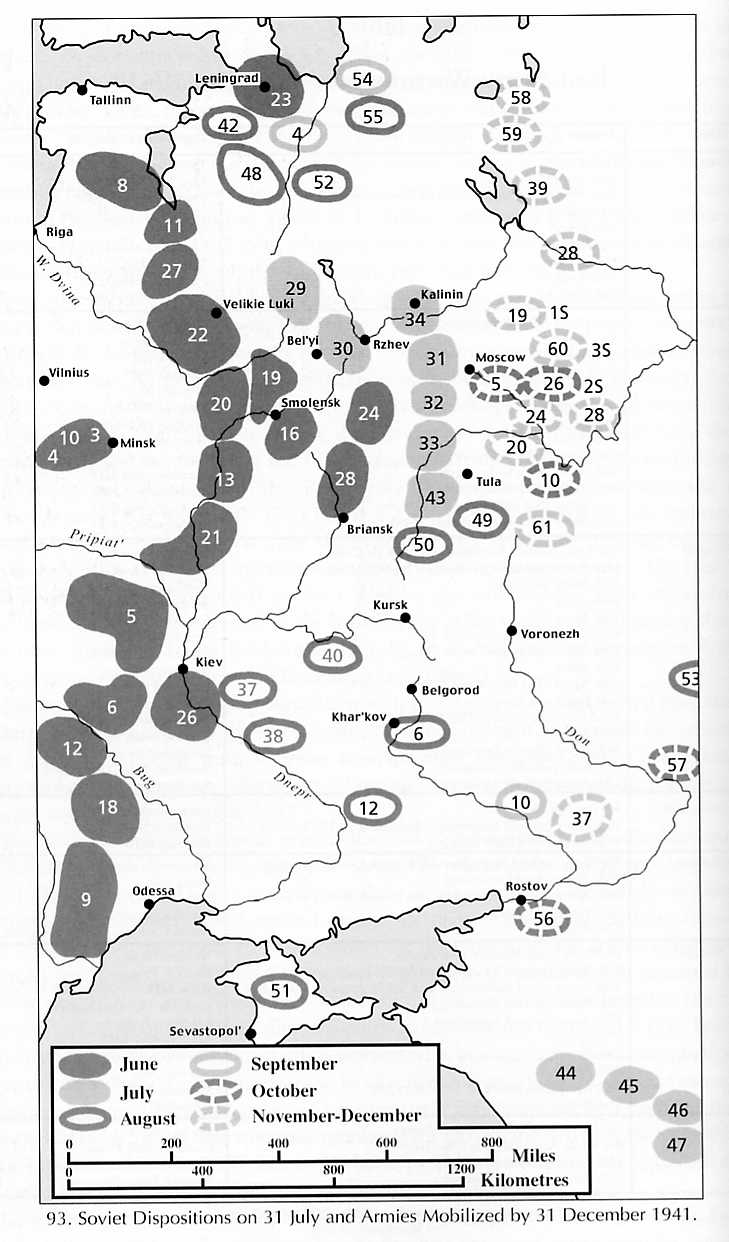

and 2 in December (see Table I).27

This mobilization system, in conjunction with active duty units that moved from

the eastern military districts to the west, retained enough strength to generate

the armies that defended Moscow from October through early December 1941. The

Stavka replicated its mobilization efforts the following year when it formed

10 additional reserve armies in the spring of 1942

The Soviet mobilization system generated a total of approximately 285 rifle

divisions, 12 re-formed tank divisions, 88 cavalry divisions, 174 rifle brigades

and 93 tank brigades by 31 December 1941. Despite heavy losses, these additions

brought the Red Army's line strength to 401 division equivalents on 1 August,

450 division equivalents on 1 September and 592 division equivalents on 31 December.

At the same time, the army's personnel strength rose from 5,373,000 on 22 June

to 6,889,000 on 31 August and an estimated 8 million on 31 December. These totals

included 97 divisions transferred from the east to the west and 25 'People's

Militia' divisions raised in Moscow and Leningrad.28 (The latter were made up

primarily of militant urban workers who, in some cases, lacked the physical

stamina and military training necessary to be effective soldiers.) Whereas prewar

German estimates had postulated an enemy of approximately 300 divisions, by

December the Soviets had fielded more than twice that number. This allowed the

Red Army to lose more than 4 million soldiers and 200 divisions in battle by

31 December, roughly equivalent to its entire peacetime army, yet still survive

to continue the struggle.29

Of course, the prewar and mobilization divisions were by no means equivalent.

For all their shortcomings, the divisions lost in the first weeks of battle

were far better trained and equipped than their successors. The newly mobilized

divisions and brigades lacked almost everything except rifles and political

officers. Perhaps more importantly, they had little time to train as units,

to practice procedures so that soldiers and subordinate units knew their roles

in combat. The continued poor performance of Soviet divisions in the fall and

winter of 1941 must be viewed in light of the speed with which they were created

and the total inexperience of their commanders and troops. This performance,

however, contributed to the German impression of an inferior enemy who did not

realize that he had already been defeated.

Saving Soviet Industry.

The Red Army's equipment and ammunition shortages of 1941 were exacerbated

by the massive redeployment of Soviet heavy industry to avoid capture. Prior

to the German invasion, the vast majority of Soviet manufacturing capacity was

located in the western portion of the country, particularly major industrial

areas such as Leningrad and the eastern Ukraine. As early as 24 June, the GKO

created a Council for Evacuation to relocate these plants eastward to the Urals

and Siberia. The task of coordinating this massive undertaking fell on N.A.

Voznesensky head of the Soviet industrial planning agency GOSPLAN. Voznesensky

was one of the few senior civilians who dared to speak bluntly to Stalin; on

4 July he won approval for the first war economic plan. The Council's deputy

chairman, the future premier A.N. Kosygin, controlled the actual evacuation.

Voznesensky and Kosygin had to do more than simply move factories and workers,

however. In the centrally directed Soviet economy, nothing would happen without

careful advance planning to ensure that these factories would mesh with existing

plants and raw material supplies in the new locations. Workers had to be housed

and fed in remote towns whose size tripled overnight. Electric plants had to

keep operating until the last possible moment to facilitate dismantling in the

old locations, then be moved and re-assembled at the new sites. All this had

to be done at a point when the industrial sector was shifting gears to accommodate

wartime demand and the periodic loss of skilled laborers to the Army.30

The most pressing problem was the evacuation of the factories, especially in

the lower Dnepr river and Donbas regions of the Ukraine. Here the stubborn delaying

tactics of the Southwestern Front paid dividends, not only by diverting German

troop strength away from Moscow but also by giving the Council for Evacuation

precious time to disassemble machinery. The long lines of railroad cars massed

in the region puzzled German reconnaissance aircraft. Eight thousand freight

cars were used to move just one major metallurgy complex from Zaporozh'e in

the Donbas to Magnitogorsk in the Urals. The movement had to be accomplished

at great speed and despite periodic German air raids on the factories and rail

lines. In the Leningrad area, the German advance was so rapid that only 92 plants

were relocated before the city was surrounded. Plant relocations did not begin

in this region until 5 October, but by the end of the year a former Leningrad

tank factory was producing KV-ls at a new site in the Urals. More than 500 firms

and 210,000 workers left the Moscow area in October and November alone.

All this machinery arrived in remote locations on a confused, staggered schedule

with only a portion of the skilled workforce.31 By the time the trains arrived,

bitter winter weather and permafrost made it almost impossible to build foundations

for any type of structure. Somehow the machinery was unloaded and reassembled

inside hastily constructed, unheated wooden buildings. Work continued even in

the sub-zero night, using electric lights strung in trees and supplemented by

bonfires. In total, 1,523 factories including 1,360 related to armaments were

transferred to the Volga, Siberia, and Central Asia between July and November

1941. Almost 1.5 million freight cars were involved.32 Even allowing for the

hyperbole so common to Soviet accounts, this massive relocation and reorganization

of heavy industry was an incredible accomplishment of endurance and organization.

Because of the relocation, Soviet production took almost a year of war to reach

its full potential. The desperate battles of 1941 had to be fought largely with

existing stocks of weapons and ammunition, supplemented by new tanks and guns

that often went into battle before they had even been painted.

Scorched Earth.

Despite their best efforts, the Council for Evacuation was unable to relocate

everything of value. In the case of the Donbas mines, where 60 per cent of the

USSR's coal supplies were produced, evacuation was impossible. In such cases,

the Soviet regime not only had to survive without facilities and resources,

but it had to ensure that the invaders could not convert those facilities and

resources to their own use. The painfully harvested fruits of Stalin's Five

Year Plans had to be destroyed or disabled in place.

Much of the Soviet self-destruction focused on transportation and electrical

power. Railroad locomotives and locomotive repair shops that could not be moved

were frequently sabotaged, a fact which proved important in the winter weather,

when German-build locomotives lacked sufficient insulation to maintain steam

pressure. The Dnepr river hydroelectric dam was partially breached by Soviet

troops as they withdrew, and workers removed or destroyed key components of

hydro-turbines and steam generators throughout the region. In the countryside

the extent of destruction of buildings and crops varied considerably from region

to region. On the whole, Russia proper had more time to prepare for such destruction

than did the western portions of Belorussia and the Ukraine.

Moscow's success in evacuating or destroying so much of its hard-won industrial

development shocked German economic planners, who had counted on using Soviet

resources to meet both Hitler's production goals and their own domestic consumer

demands. Soviet raw materials such as chromium, nickel and petroleum were vital

to continued German war production, and captured Soviet factories had promised

an easy solution to overcrowding and labour shortages in Germany proper. Moreover,

the successful evacuation of the Soviet railroads forced the Germans to commit

2,500 locomotives and 200,000 railcars to support the troops in the east. This,

in turn, meant that the Germans had to convert large portions of the captured

rail network to their own, narrower gauge, instead of using the existing, broader

Russian gauge.33 Thus, the Soviet evacuation effort not only preserved industrial

potential for future campaigns but also posed a continuing and unexpected drain

on the German economy.

Still, despite all efforts a considerable portion of the industrial plant and

the harvest fell into German hands. Hitler increasingly defined his objectives

for 1941 in terms of seizing additional economic resources, and the German advance

sought to satisfy those objectives.

Reflections.

The postwar Soviet leadership often boasted that, during the initial days of

its Great Patriotic War, the Soviet Union and Red Army experienced the equivalent

of a nuclear first strike, yet survived. While overstated a bit, this claim

is not far from the truth. Hitler's naked aggression dismembered and destroyed

a vast chunk of the peacetime Red Army and caught the Soviet defence establishment

in the middle of already disruptive wholesale institutional reforms. In additional

to the physical destruction it wrought on the Red Army and the political and

economic infrastructure in the western Soviet Union, it thwarted orderly mobilization

of military forces and the economy for war and produced chaos in force deployments.

To Hitler's surprise, however, once set in motion, despite the disruption, the

mobilization proceeded apace, generating forces at a speed that first escaped

and then staggered the Germans' imagination. Even though the mobilized armies,

divisions and brigades were shadow and threadbare versions of what they were

supposed to be, the mobilization process ultimately proved that, in many respects,

quantity is an adequate substitute for quality. In addition, amid the chaos

and destruction, the GKO, Stavka and General Staff were able to reorganize their

forces so that they could continue the fight, survive, and even turn the tide

of battle by early December.

However, all that Soviet comma nd organs were able to accomplish in the military

and economic realms in the summer of 1941 were temporary expedients designed

only to prolong the fight and halt the German juggernaut somehow and somewhere.

In early July it was by no means a certainty that the Red Army could do so.

(Glantz 59-74)