HISTORIES=PLATEAUS by Carlos

A. Romay Vergara

1/5. CONCEPTS AND DIAGRAMS.

Summary:

1. Diagrams and Concepts.

2. The Origin and the Organization of Concepts: The

Tree and the Rhizome.

A. The Origin of Concepts.

A.1. The Pictogram.

A.2. Fantasy.

A.3. The Idea or Enunciation.

A.4. The Representation.

A.5. The Diagram.

B. Organizations and Structure.

3. Representations: The ‘Tracing’ and

the ‘Map’.

4. The Materiality of Rhizomes at the Architectonic and Urban

Level.

5. The Map of History

6. Bibliography

The objective of this essay is to evaluate the organization

of concepts in plateaus and the representation of concepts as ideograms. The

hypothesis identifies the History of Architecture as a plateau composed of concepts

of the organization of Space.

1. Concepts and Diagrams.

The elements that compose the History of Architecture are lines

of action produced by concepts on space, whether architectural or urban space.

The necessity of projecting these concepts into materiality has produced a wide

field for representation. Furthermore, materiality

has led to the evolution of the processes of design and representation.

Concepts and their representation may comprise different instances

of time: the past and the future. In both cases, the internality of the representation

is different. Traditionally, in the representation of concepts of the past,

the proposition of space was precluded since in first instance what was regarded

was analysis. Nevertheless, futurity may be introduced in the formulation of

timeless concepts in the form of new concepts projected to future enterprises.

The development of the concepts analyzed may also derive in the difference as

consequence of the analysis. Jean François Lyotard wrote that the historian

must reconstruct using concepts (Lyotard, Phenomenology; p.128). Hence, historic

analysis cannot be severed from proposition.

What is the importance of investigating the origin of concepts

into architectonic practice? Is it possible to re-orient the practice of Architecture

from the social definition of concepts? As David Harvey, professor of Geography

and Environmental Engineering of the John Hopkins University if Baltimore wrote,

every discipline oriented thru society formulates concepts that are extensive

to the social relationships in practice: ‘…social sciences formulate

concepts, categories, relationships and methods that are not independent from

the existent social relationships. As such, concepts are product of the phenomenon

they try to describe…Our task is to exercise the power of thinking in

to formulate applicable concepts and categories, theories and arguments to contribute

to humanizing social change. These concepts and categories cannot be formulated

on the abstract. They must be elaborated realistically in regard to events and

actions that deploy around us…Nevertheless all these actions and information

do not mean unless we synthesize them into convincing models of thinking’(Harvey,

130-151).

A model of thinking is a super-structure that regulates as

well as transforms itself. This aspect is fundamental to provide Architecture

with purposes different to those of the strict reproduction of capital. Only

through the redefinition of Architecture within the social system of which it

forms part it might be possible to attain prototypes of application.

Harvey adds: “Marx established that the perception, elaboration

and representation of concepts happens through reflexive abstraction by the

subject that observes…It is not possible to consider that concepts and

categories have an independent existence and that they are always truly universal

abstractions. The structure of knowledge may be transformed by its own internal

laws of transformation…Concepts are ‘produced’ occasionally

(including a series of pre-existent concepts) meanwhile they may be considered

as producers of agents in a real situation. It is irrelevant asking if concepts,

categories and relationships are ‘true’ or ‘false’.

Instead, we must ask ourselves what produces them and what they produce…Hence

there is the criteria that these theories cannot be used if abstracted from

an existent situation. On the other hand they must be applied through a study

of the modalities in which theories become a ‘material force’ in

society and through their impact on social action…The meaning of each

concept is re-adjusted according to social relationships. In order to perform

this technique it is fundamental the criteria that categories and concepts establish

(or at least appear) a mutual relationship that reflects the condition of society

itself’. (Harvey, p. 313-316).

Hence, the origins of the proposing of architectural concepts

are social and material (non-teleological). Nevertheless, what happens with

the organization of concepts? As Hollander architect Herman

Hertzberger points out: “The researcher does not start anywhere, he

does not begin without an idea, a hypothesis, about what he expects to find,

and where…” (Hertzberger, p.115). The design starts with intention,

with vectors that push the yet-not formed concepts into specific directions.

The vectors of a complex economy for the object include the relationships among

material, program and event, and of course, the economic tension that the object

produces in the city and the region, and among buildings as well. On the other

hand, concepts related to the applied investigation of historical lines establish

other relationships, in a process that formulates actions that take place in

different times and spaces.

Ben van Berkel, Hollander

architect, theoretician and critic, editor of the 23rd

number of the ANY magazine (number is devoted to diagrams in Architecture),

extends on the ambiguity of the concept: “Architecture still articulates

its concepts, design decisions, and processes almost exclusively by means of

a posteriori rationalizations… The demand to present the ‘right’

solution, even when the contents of that concept have become very uncertain,

propagates architecture’s dual claims of objectivity and rationality”.

(Van Berkel, p.19).

Hertzberger compares the concept with an enduring structure

for a more changeable ‘infill’. As Hertzberger points, the concept

allows interpretations since its description is ambiguous and open. The concept

as structure works as a frame, as a structure coated by layers stirring cohesion

and coherence on narrative basis. The master plan is a normative and mandatory

representational device that Hertzberger opposes to the concept. (Hertzberger,

p.100). On the other hand, the selection of a wrong concept for the analysis/proposal

is not useless. A wrong concept may prove almost immediately its flaws, and

help point another direction: “The concept may be a compass, but is hardly

the final destination of the design process. The end product may be nothing

other than a development and interpretation of that concept, the way one might

apply or render an overall vision. Thinking in terms of concepts, models, strategies,

etc.-deriving as this does from seeking out the essence of what you are occupied

with-does mean that there is a danger of that abstraction all too quickly leading

to simplification. The issue is how to couch complexity in simple formulas…you

have to know exactly where you are ahead: you have to have a concept…The

concept contains the conditions you wish to fulfill, it is a summary of your

intentions; of what needs saying; it is hypothesis, and premonition. There may

be no quest without premonition; it is question of finding and only then seeking”.

(Hertzberger, p.101-117).

2. Organization

of the Concepts: The Tree and the Rhizome.

A. The Origin of Concepts:

A. The Origin of Concepts:

Concepts are not produced from void. From the past, real and

virtual experiences allow the formation of a collection of ideas that are assembled

in different configurations and that may be important in order to propose the

future or to unveil the past. Unveiling the origin of concepts is important

to understand that its is an evolved phase of thinking. This phase has had previous

phases in order to accomplish representation. Author Piera Castoriadis wrote

over the definition of representation: “The activity of representation

is understood as the psychic equivalent of the work of metabolizing characters

of organic activity…This definition may be applied entirely to the work

that operates in psyche. Despite that, the absorbed and metabolized ‘element’

is not a physical body but an informational element. If the activity of representation

is considered as a task common to psychic processes, we may tell that its goal

is metabolizing an element of heterogeneous nature converting it into a homogeneous

element to the structure of each system… The representations originated

in its activity would be… the pictographic representation…the fantasized

representation, … (and) the idealized representation or enunciation. The

instances originated in the reflection of this activity would be designated

as the representing, the fantasizing…, the enunciating or the Self [Je]…The

objective of the Self’s work is to forge an image of the world’s

reality around it and on whose existence it is informed in order to be coherent

with its own structure…The concept of reality for the subject is no more

than the whole of definitions given by the cultural discourse’. (Castoriadis,

p.23-26).

(It is important the point where Castoriadis establishes that

reality is nothing more than the adequacy to cultural discourse. The ‘Self’

works in order to adequate information until it fits it in the concept of reality

that every individual has. We have then that reality is ambiguous for two individuals

proceeding from different cultures. This is particularly critical for the proposition

of public and semi-public spaces. Architecture and Urbanism must appeal to universal

schemes of integration and on the way attain processes of ‘exportation

of local concepts’ that may have universal basis. This process is attained

though adaptation to different conditions).

The structure of these inferior and superior modalities of

rationalization is important in order to understand their consecution to the

concept:

A1. The Pictogram:

‘The Psyche’s constant definition: nothing may

appear in its field if it has not been previously metabolized into pictographic

representation. The pictographical representation of the phenomenon constitutes

a necessary condition for its psychical existence: this law is as universal

and irreducible as the law that decides the object’s audibility or visibility

conditions…The conditions of representation that objects must have in

order to attain the material used by the Original may just be reconstructed

in later phases’. (Castoriadis, p. 42).

The pictogram is a universal image that derives from stimulus

or information. It is the base for the appearance of superior modalities of

thinking. Its origin is involuntary and it constitutes a concoction of sensations

and different stages of thinking that must be rationalized a posteriori. Castoriadis

adds that using the term ‘information’ she refers to the role accomplished

by sensorial functions (Castoriadis, pg. 48).

A.2. Fantasy:

Castoriadis wrote that‘…what characterizes fantasized

production is the mise-en-scène of the representation of two spaces,

one of which is subdued to the absolute power of one of them…Fantasy and

unconscious originate in the joint work…of the primary and of the primal

judgment imposed by the principle of reality. They regard the presence of an

exterior and isolated space. This first participation of the principle of reality

in the work of the Psyche is responsible for the heterogeneity between pictographical

production and fantasized production’. (Castoriadis, p. 72).

Fantasy is then a first encounter with reality. It is the separation

of the original and primary spaces. Fantasy is not yet an absolutely rational

space. In the transition from pictogram to fantasy the individual decides the

penetration into the space of reality. Fantasy differences from the simple gathering

of information through later phases of rationalization.

A3. The Idea or Enunciation.

‘Any source of excitement and any information accomplish

access to the register of the Self only providing the representation of an “idea”.

Every activity of the Self translates into “thinking flux” implicitly

or explicitly. A truly “simultaneous translation” from any form

of conscious experience of the Self into “idea” occurs’. This

translation represents a latent background that is habitually silent but that

generally the Self may make present through an act of reflection over its own

activity’. (Castoriadis, pg. 62)

Castoriadis adds that the Idea is function of ‘intellection’.

As a new form of activity it is part of pre-existent partial functions. Hence,

the activity of thinking is a condition for the existence of the Self. Furthermore,

activity generates its own Topos. Castoriadis adds that every experience and

every act imply the co-presence of an ‘idea’ that allow its thinking

and naming (Castoriadis, pg. 62-63). (The appearance of a place, a ‘Topos’,

is fundamental for the notion of Idea. In the same way that in material life

a ‘place’ emerges from an indifferent space through the will of

delimitation, in the same analogous way Idea differences from the space of fantasy

and pictogram limiting its own different and virtual space).

According to Harvey, social processes accept the possibility

of combining superior and inferior structures. As social totality is in relationship

to all its parts (a posture assumed by Harvey), this combination may be applied

to all structures within totality: ‘Any structure of superior category

may be obtained from an inferior category through transformation. Under these

conditions there may emerge a hierarchy of structures through a process of internal

difference. Hence, there may coexist superior and inferior category structures’.

(Harvey, pg. 306). The objective of the combination of superior and inferior

chains validate, preserve and criticize the structure where they work (in this

case, the structure of thinking). Harvey proposed the existence of theories

(as part of the process of intellection) that are revolutionary, counter-revolutionary

and favorable to the status quo (Harvey, pg. 314). This implies that concepts

may assume these characteristics of resistance and conformity as well.

On the other hand, the relationship between word and idea is

fundamental for the expression of the idea, according to Castoriadis: ‘The

image of thing is the previous necessary condition for the image of word to

include itself: the primal scenic follows the pictographical and prepares the

spoken that follows…The real difference between an unconscious representation

and a pre-conscious representation (idea) consists in the fact the first relates

to known materials, meanwhile…the pre-conscious is associated with verbal

representation…The hypotheses may be formulated as follows: the representation

of idea demands that the Psyche acquires the possibility of uniting the representation

of word to the representation of things through acoustic perception only when

this last may be converted into the perception of a signifimayce…’.

(Castoriadis, p. 88-90).

A. 4. The representation:

In ‘Matière et Mémoire’, Henri Bergson

divided the mix (Representation) in two divergent directions: matter and memory,

perception and remind, objective and subjective (Deleuze, Bergsonism, pg. 53).

Deleuze pointed out that experience grants us with mixes and that the status

of mix does not consist solely in joining elements that differ in nature, but

in welding them in such conditions that differences within them may not be divided

since their constituent nature (Deleuze, Bergsonism, pg. 32). Furthermore, Deleuze

wrote that emotion is always linked and dependant on representation: ‘In

the mix of emotion and representation, emotion is the potency; we shall not

avoid seeing the nature of emotion as a pure element. Emotion truly precedes

any representation: it is generator of new ideas. Properly, it does not have

object, only an essence that extends over diverse objects: animals, plants,

the whole nature…’ (Deleuze, Bergsonism, pg. 117). Hence, Deleuze’s

conception is mainly phenomenological and eidetical, referred to essences. Representation

for Deleuze is not objective, since it provokes emotions that generate new ideas.

We may talk then of representation and feed-backing, or rather feed-forwarding

the future, since in this conception the movement through time extends to a

representation that might in turn modify the representation of the object again,

and so on endlessly. Time’s scale (and duration) is essential for this

Deleuzian conception based on the philosophical work of Bergson.

Coincidentally, Andrew

Benjamin wrote over the ‘space of melancholy’ that is open in

representation. In ‘Representation-Melancholic Spaces’ (in Benjamin’s

book ‘Architectural Philosophy’), Benjamin wrote that what is represented,

in the case of the ideogram or pictographic representation of the future, is

the non-existence of the represented object (this definition extends even to

the diagram). Futurity is essential in this conception: Absence unchains a sense

of loss that is called melancholy (‘Architectural Philosophy’, pg.

148-151). In consequence, representation is an emotive space. This establishes

a coincidence with Deleuze’s explanation on the origin and representation

and to its connection with essence.

On the other hand, there is a fundamental difference between

an idea with verbal consequence and an idea with graphical consequence. A phrase

that cannot be articulated diminishes its potential for comprehension. Nevertheless,

graphical representation find a a great gamut; from pre-graphics as the diagram

to indexed and technical drafting that make use of syntax and symbols as languages.

In the last, the omission of a symbol may produce serious differences in the

implementation of a technical plan. On the other hand, the diagram is subject

neither to rules nor syntax, and its verbal equivalent is impossible. The diagram

does not need the rules that word require for their comprehension.

But, are Concept and Idea the same? Herman Hertzberger points

out that there is a difference, and that concepts are the communicational phase

of the idea. The concept powers the idea at the graphical level: “(The

concept) …encapsulates all the essential features for conveying the idea,

arranged in layers as it were and distinguished from all future elaborations

as, say, an urbanistic idea, set down in a masterplan…the concept will

be more layered, richer and abiding not only (to) admit more interpretations

but (to) incite them to. …Concepts, then, are ideas expressed as three-dimensional

ideograms”. (Hertzberger, p.100-101). Hertzberger states that the concept

has ‘layers’ and ‘strata’. This is a almost geological

vision that takes the concept to the category of tangible ‘material’.

He does not specify how this combination of layers produces interpretations.

Probably ideas arrange in three-dimensional combinations of layers (and through

time too). Being the order of ideas and graphics critical for the determination

and incitation of interpretations, a process of mediation is necessary. Hertzberger

adds that the concept may have graphical expression and that this expression

may be translated into a diagram. On the other hand, Rosental and Ludin equalize

the concept to Idea and center ts signifimayce in practical and syntactical

function (Rosental and Ludin, pg. 76 and 372).

In synthesis, the concept overcome previous instances of rationalization

as a whole of ideas assembled by affinity. Under certain degrees of difficulty,

concepts have the possibility of being implemented from easiness to extreme

complexity. The concept may be affine or contradictory to the super- structures

where implemented. My hypothesis is that in the course from ideas to concepts

territorializing occurs. In this phase the Concept becomes excluding in relationship

to others. A proposal with two contradictory concepts cannot exist since one

of them works in order to invalidate the other. There must be a crisis of the

Concept in order to attain its change, dissolution, re-composition and re-structuring

with ideas that are internal or external to the concept in crisis. Therefore

the crisis of Concept implies the crisis of a certain process of design.

On the other hand, is it possible to graphically represent

a concept?

The apparent controversy emerges between authors like Hertzberger

for whom the concepts are already in position of originating ideograms and others

like Karl Chu for whom the concepts cannot yet be graphics. If they could, it

would be just partially, as points in space to be connected. In Chu’s

essay, ‘The Cone of Immanenscendence’ (in ANY # 23, Pg. 39), he

points that concepts are spatial coordinates and that they require of diagrams

in order to give birth to the representation of their possibilities of configuration

(please refer to the example of the connection of ordinates in the chapter entitled

‘Instructions’).

Chu refers to immanence as the plane of all universal existences in the mind:

‘A renewal of the image of the plane would therefore affect the image

of diagrammatic features registered on the plane. The plane of immanence is

an image of thought which is constituted by the construction of concepts, according

to Deleuze and Guattari. Concepts are events defined as concrete assemblages

analogous to the configurations of a machine, whereas the plane is the abstract

machine of the absolute horizon of events. Deleuze and Guattari interpret diagrams

as trackings of dynamic movements, while concepts function as intensive ordinates

of these movements in the plane’. (ANY #23, Pg. 39).

Furthermore, authors like Stan

Allen point out a difference between the possibilities of the concept and

the potential of the diagram to absorb graphical configurations. Allen refers

to the impossibility of translating abstract texts into graphics in his essay

‘Diagrams Matter’ in ANY # 23: ‘…diagrams are not “decoded”

according to universal conventions, rather the internal relationships are transposed,

moved part by part from the graphic to the material or the spatial, by means

of operations that are always partial, arbitrary, and incomplete. The impersonal

character of these transpositions shifts attention away from the ambiguous,

personal transpositions of translation and its associations with the weighty

institutions of literature, language, and hermeneutics. A diagram in this sense

is like a rebus. To cite Kittler again: “Interpretive techniques that

treat texts as charades or dreams as pictures have nothing to do with hermeneutics,

because they do not translate”. (Allen in Diagrams Matter, in ANY # 23,

pg. 17, in reference to translation and transposition, please refer to the essay

entitled ‘ Connections

and Links in Time’).

Hence, Allen assimilates the concepts to abstractions that

are not yet in possibility of being graphically transposed. The difference lies

in the fact that both concept and diagram are in different structures and in

different systems of rationalization. The concept may be assimilated as consequence

of the last instance of rationalization that Castoriadis define as ‘idea

or enunciation’ which attains mainly verbal expression.

Furthermore, in Gregg

Lynn’s essay ‘Forms of Expression: The Proto-functional potential

of Diagrams in Architectural Design’, he points out that ‘…a

not so subtle distinction should be made between concepts; whose development

is nascent and defined through possibilities, and ideas; which imply not only

points of origin but also teleological progression’. (Croquis #72, Ben

Van Berkel, p. 17).

If we understand the concepts as abstractions or charades,

translating a concept would be, on one hand, if not impossible at least incomplete

as method. (According the Collins Ductionary, a charade is ‘a game in

which one team acts out each syllable of a word or phrase, which the other team

has to guess’. Concepts as ‘transparency’ and ‘lightness’

cannot be expressed out of a metaphorical level (for instance, represented by

‘glass’ and ‘feather’ respectively) but only the level

of form and communicability would be solved. Important issues for Architecture

like space and program cannot be analogically represented through graphics (for

instance perspectives) that depend on cultural discourse and training in order

to be understood. The representation of concepts directly would be incomplete

in this case.

Ben Van Berkel,

wrote about the impossibility of the direct translation from concepts into ideograms:

“No condition will let itself be directly translated into a fitting or

completely corresponding conceptualization of that condition. There will always

be a gap between the two. For this same reason, concepts such as repression

and liberation may never be directly applied to architecture. There has to be

a mediator…Previously, if the concepts of repression or liberation, for

example, were introduced into architecture, a complex formal expression of this

concept would be reduced to a sign with one clear meaning, which would subsequently

be translated back into a project. This reductive approach excludes many possibilities

in architecture. While concepts are formulated loud and clear, architecture

itself waits passively, as it were, until it is pounced upon by a concept”.

(Van Berkel, in ‘Diagrams, Interactive Instruments in Operation; in ANY

# 23, p.21).

The verbal expression of a diagram, on the other hand, would

be impossible as well, since the diagram is a map of multiple configurations,

sometimes in astounding numbers. Please refer to the map (diagram) that describes

the present book in the essay ‘Instructions’. In order to found

my argument, I remind Castoriadis establishing the nexus between idea (concept)

and word as condition for its existence. Being the idea expressed in words,

it creates a text which cannot be translated into graphics but incompletely

and ambiguously. (Combining words and graphics or words and spaces is another

possibility. Furthermore, the joint of signs and spaces is ambiguous, since

they both are in the same category of impossibility of direct communication.

Nevertheless, Architecture cannot communicate; it is not a vehicle of communication.

If someone pretended so, it is within a discourse where the elements accomplish

ambiguous operations of expression).

If we follow the argument about the impossibility of direct

translation of a concept into graphic representation, we may speculate that

the mental and spatial position of the diagram is mobile. It may be found, for

instance, half way between fantastic representation and idea, since it is properly

neither an enunciation nor a fantasy. Nevertheless, as the relationship that

the diagram describes occur through multiple connections in any space and time

(in a plateau, as we shall see later), it is not subject to rules and not even

to physics (through vertical, horizontal, transversal connections, leaps in

time, travels of thousands of kilometers in seconds, etc.). The movement in

these plateaus may be assimilated more to movements in fluids where there is

no mechanical resistance. The diagram focuses more in possibilities of flux

and configuration. This does not imply that a very explicit diagram cannot be

used as political instrument of resistance providing, for instance, extreme

degrees of representation of des-centralization or autonomy.

In consequence, the stage of rationalization that the diagram

uses is displaced by its potential of mimicking fluxes and configurations. This

potential extends since the diagram has not foreclosed its work as in the case

of the ‘enunciation’. The diagram may also displace to inferior

instances of rationalization as the pictograms and information, fantasy, stimulus,

etc. In other words, it may use all sort of resources that language and words

cannot. Hence, I conclude that the diagram does not proceed from a concept,

and that there is no linearity between process of intellection and graphical

representation. The diagram may appear in phases that are previous to the idea

(enunciation), and even mutate it. This divergence creates a conflictive relationship

expressed by Castoriadis: ‘That is why thought, the primal figuration

and the pictogram preserve a more or less open conflictive relationship’.

(Castoriadis, p. 110)

In summary, the ideogram or diagram’s potential is in

a level different from that of verbal representation, since verbal expression

contributes with narrative levels meanwhile diagrams contribute with configurative

levels. Verbal narration of a space may also incite fantasy and produce ‘repetition

and difference’ through the consecutive relation among people. This level

of ambiguity may be found in ideograms as well. Nevertheless, since architecture

needs under certain circumstances to be material, it requires the graphical

document for its construction (other architectures stay in an the immaterial

plane where their potential lies, as the Ferriss’ s futurist draws and

Lebeus Woods’s inciting draws). The ideogram then assumes a phase of mimesis

since it imitates instructions and possible (and impossible) configurations.

It cannot be restricted through caesura. Its coherence is not questionable,

since it does not work at the level of the intellect as finished stage (the

diagram constitutes a plane of immanence and totality which lies in a graphic

of potentialities. On the other hand, analogical diagrams are produced by the

intellect as finished configurations, as in Frank Lloyd’s transposition

of diagrams and plans. Nevertheless, this last instance precludes the possibilities

of exploring and proposing configurations).

A. 5. The Diagram.

Zaera Polo and Farshid Moussavi

write in ‘FOA Code Remix 2000’ that ‘…a diagram is essentially

a material organization that prescribes performance. It does not necessarily

contain metric or geometric information’ (2G # 16; p. 140). On the other

hand, FOA explains that ‘…diagrams and computers enable you to work

at a very abstract level and to integrate changing or differentiated conditions

through the process while allowing local structures or contingencies to inform

the final result’ (2G # 16, FOA; p. 137).

Moreover, Peter

Eisenman wrote on the definition of ideograms, which diagrams are part of:

“Generically, a diagram is graphic shorthand. Though it is an ideogram,

it is not necessarily an abstraction. It is a representation of something in

that it is not the thing itself…It may never be value-or meaning-free,

even when it attempt to express relationships of formation and their processes…Although

it is often argued that the diagram is a post-representational form, in instances

of explanation and analysis the diagram is a form of representation”.

(Eisenman in ‘Diagrams: An Original Scene of Writing’; in ANY #23,

p. 27)

In architectural magazine ANY # 23, Stan Allen wrote that diagrams

are the best means to engage the complexity of the real: “A diagram is

a graphic assemblage that specifies relationships between activity and form,

organizing the structure and distribution of functions….The diagram does

not point towards architecture’s internal history as a discipline, but

rather turns outward, signaling possible relations of matter and information.

But since nothing may enter architecture without having been first converted

into graphic form, the actual mechanism of graphic conversion is fundamental.”

(Allen, in Diagrams Matter, in ANY # 23, p.17). Furthermore, Allen wrote that

the diagram is more a productive device that a collection of graphics that only

work in the narration of the plot of design. Hence, diagrams may also work unveiling

Historic connections and projecting them into new possibilities.

Van Berkel extends on the features of the diagram: “More

to the point is the general understanding of the diagram as a statistical or

schematic image…understood as reductive machines for the compression of

information…The condensation of knowledge that is incorporated into a

diagram may be extracted from it regardless of the significance with which the

diagram was originally invested….The diagram conveys an unspoken essence,

disconnected from an ideal or an ideology, that is random, intuitive, subjective,

not bound to a linear logic that may be physical, structural, spatial, or technical”.

(Van Berkel, p.20). Van Berkel’s notion that the diagram is neither structural

nor ideological reminds the description of Guattari and Deleuze of the rhizome.

Moreover, as a representational device, the diagram has the

potential of revealing new organizations: “Although diagrams may serve

an explanatory function, clarifying form, structure, or program to the designer

and to others, and notations map program in time and space, the primary utility

of the diagram is as an abstract means of thinking about organization...Unlike

classical theories based on imitation, diagrams do not map or represent already

existing objects or systems but anticipate new organizations and specify yet

to be realized relationships”. (Allen, in Diagrams Matter, in ANY # 23,

p.16).

The diagram has two purposes. In Design, it has the potential

of forecasting the yet to come, and in Historical analysis, the diagram has

the potential or assessing connections that have been undiscovered and to project

them into the future. Hence, a productive relationship exists between the architectonic

project and History: “The forward- looking tendency of diagrammatic practice

is an indispensable ingredient for understanding its function; it is about the

‘real that is yet to come’. (Van Berkel, p.21). Deleuze wrote that

thinking the past against the present (resisting the present) is performed not

for an identical return of the past, but (quoting Nietzsche), ‘in favor…of

a future time’. (Foucault, p.155).

Gregg Lynn, in his essay ‘Forms of Expression: The Proto-Functional

Potential of Diagrams in Architectural Design’, in Croquis #72; establishes

a difference between from-the-beginning concrete mechanical and technical assemblages

and the abstract machines (diagrams), that are conceptual statements (part of

a discourse) with many possibilities for reconfiguration and transformation.

Lynn wrote that the effects of abstract machines trigger the formation of concrete

assemblages when their virtual diagrammatic relationships are actualized as

a technical possibility. Concrete assemblages (as technical details, scalar

systems that extend to the whole project as in the work of R+U, where a detail

is fractal in its relationship to structure, etc), are realized only when a

new diagram may make them cross the technical threshold. Lynn wrote that ‘…it

is the diagram that select new techniques....These diagrams bring functions

of structure, circulation, enclosure and manufacturng into existence from an

origin that is initially meaningless and useless. These diagrams and this design

method is proto-functional...The sites, programs and structures of these projects

are brought into existence through a proto-functional intuition...’ (Croquis

#72, Ben van Berkel, pg. 29).

Therefore, the concrete assemblage may work as a diagram too

when it assumed such characteristic. Herzog

& de Meuron’s work, that of Gigon

and Guyer and the firsts works of Van Berkel make use of tectonic diagram

as an explanation of the project. In this cases, materiality displaces the abstraction

of the diagram and represents reality, turning into analogical diagrams, that

is, without any mediation. Nevertheless, the potential of these kind of diagram

is sometimes limited to the envelope, being the architect’s responsibility

to establish the relationship among programs, forms and events. (William Curtis

in his essay ‘The Unique and The Universal: A Historian's Perspective

on Recent Architecture’, wrote that ‘…so many of Herzog /de

Meuron's recent projects start out with an alluring facade idea exploring materiality,

ambiguity, allusion, 'object-hood', etc., but the same intensity of perception

is not sustained on interiors which sometimes end up being quite ordinary and

flat, as do the plans. The totality of the building is not always infused with

the generating ideas’. Croquis #88/89, pg. 15).

Furthermore, Zaera Polo, in his essay ‘A World Full of

Wholes’, wrote that ‘Herzog & De Meuron's work is conceptual

and diagrammatic, and its material organization operates from a diagram that

controls the totality of the work (Croquis #88/89; pg. 319). To Zaera Polo,

the Basel’s team design is machinic since it ‘…posses an implacable

order that keeps the project beyond authorial expression, or even its powerful

material presence. Buildings such as the Warehouse for Ricola, the Signal Box

and the Dominus Cellars may be explained by a diagram, in an order that automatically

structures the decisions of the project, almost without any need for involvement

by the author. In this sense, despite the powerful aesthetic thrust of the work,

Herzog & De Meuron's production is largely abstract and mechanistic, and

is fundamentally determined by an initial material and constructive concept

which is capable of producing the project by pure repetition’ (Croquis

#88/89; pg. 319).

B. Organizations and Structure.

Concepts are organized into structures which are determined

by the way in which they relate their parts. These structures may also extend

to the organization of diagrams. Furthermore, diagrams are mimesis and image

of the world. (Hence, the political origin of diagrams is crux for its proposing

since the diagram is anteceded by the discourse, which must be reviewed if the

potential of the diagram is not to be precluded). The importance in writing

over structures is to define movements inside them. These movements may be static

or relational and determine the way in which we perceive the totality and the

way in which we interact with it. According to Harvey …’inside totality

separated structures exist and that it is possible to distinguish one from the

other. Structures are not “things” or “actions”. Therefore

we cannot establish its existence through observation. To define the elements

relatively means to interpret them apart from direct observation. Defining the

elements relationally means interpreting them outside direct observation’.

(Harvey, pg. 305).

Dealing with elements related with structures is important

in order to extrapolate the vision of connections to the vision of a connected

and inclusive world. Harvey refers that relationships may occur apart from the

experience of observation. This means that the study of potential relationships

among the elements within a structure cannot be neither studied nor proposed

through pragmatic methodologies. (‘In pragmatism, objective reality is

equaled to “experience” meanwhile division between the subject and

object of knowledge is established uniquely within experience’. Rosental

and Ludin, pg. 372).

Harvey adds that ‘…any structure must be defined

as a system of internal relationships in processes of structuring through the

work of their own laws of transformation. Therefore structures may be defined

through the comprehension of the laws of transformation that model them…Structures

may be considered as separated and different entities when there is no transformation

that might turn one into another…To say that structures may be distinguished

does not imply that they evolution in autonomy without influencing one on the

other. Marx… suggests that relationships among structures are in turn

structured inside totality…When we try to consider society as a totality,

then everything must be related in last terms to the economic basis of the structures

of society’. (Harvey, 306).

Furthermore, Harvey adds that structures are transformed by

internal and external relationships that produce consequence among structures.

Hence, he outlines a definition of totalitarian structures that impose their

discourse in favor of their own laws of integrity: ‘In other words, totality

is about to be structured by the elaboration of the relationships inside it…This

concept is common to Marx and to Piaget. Ollman…signals how such a point

of view influences the way of conceiving relationships among the elements and

among the elements and totality. Totality tries modeling the parts so that every

one of them is useful in order to preserve the existence and general structure

of the whole’. (Harvey in pg. 303-304 makes reference to Piaget’s

‘Structuralism’, NY, 1970).

The manner in which structures are internally conceived provides

with two different models of thinking, one of multiple transversal relationships

and another in which elements answer to vertical hierarchies. In both models,

their structures and elements provide with a gamut of scalar systems of organization.

Furthermore, it is possible to arrange combinations among hierarchical and transversal

structures.

The origin of vertical organizations is, according to Harvey,

space itself. Any space of absolute properties is a defined and unchangeable

space that provides a discourse of exclusion and segregation: ‘To say

that space has absolute properties is to say that structures, people and lots

exclude mutually in Euclidian tri-dimensional space. This concept is not by

itself an adequate concept of space …’ (Harvey, pg. 175)

Since models and structures are extensive to societies, the

hierarchical model is based mainly in forced and imposed significations expressed

in urban space, the space of differences and hierarchies by excellence: ‘The

general consequence of a hierarchical society is evident and produces tangible

results into urban spatial economy. Dominant organizations and institutions

use space hierarchically and symbolically. Sacred and profane spaces are created,

focal points accentuated and, in general, space is manipulated in order to attain

status and prestige’. (Harvey, p. 292).

The (mental and physical) spatial configuration of hierarchical

structures provides with typical organizations. Some of these spatial experiences

may be connected in a linear, consecutive fashion in which an element is pre-condition

for the next and antecedent of the previous; i.e. that an individual admits

an only active neighbor, its hierarchical superior. The individual may just

occupy a precise position (through a process of signification and subjectivation).

In this case, the formation of points that are central and pivotal produces

a configuration with the form and structure of a tree.

On the other hand, the development of transversal structures

produces another conception of the space and of social practice from which concepts

derive. Configurations are not necessarily produced at the same dimension (neither

in the same time nor in the same space). The connection of two lines in this

configuration is not sequential. In this case, an element is not pre-condition

for the other or antecedent of another. If we apply the notion of time in this

case, the connection of two random elements in this three-dimensional net may

be produced anytime. For instance in History, the connection of two random events

in different times and spaces (like groups of ideas and experiences) takes years

in order to finally establish a concept of relationship, which may finally occur

in some other geographical point and in some other time which is not the original.

Respectively, these two types of organization may be regarded

as the ‘tree’ configuration and the ‘rhizome’ configuration

on which philosophers Guattari and Deleuze extended on. Furthermore, there is

a strong relationship established between the works of Christopher Alexander

(1965, in “A City is not a Tree”) and those of Guattari and Deleuze

(of the possibilities of connecting different elements in random fashion). Nevertheless

the intentions and the consequences of the aforementioned works were different.

Alexander wrote his thesis in order compare the lack of complexity the American

cities of the 1960’s had in comparison to traditional cities where the

potential of connections was unlimited. (Harvey wrote that urban space is a

space of multiple and improvised connections that defies the hierarchy through

relations: ‘The activity of any element in a urban system may generate

certain effects…over other elements of the system…Simple observation

of urban problems indicates that an enormous multitude of external effects must

be taken into account, a fact that is recognized implicitly by Lowry (in A Short

Course in Model Design, Journal of the American Institute of Planners # 31,

pg. 158) …in his phrase “In the city, everything affects everything”.’

(Harvey, 54, 55).

Moreover, Alexander wrote in ‘The City is not a Tree’

that “…both the tree and the semi-lattice are ways of thinking about

how a large collection of many small systems makes up a large complex system.

More generally, they are both names for structures of sets.”(Alexander

in ‘A City is not a Tree’, in Jencks and Kropf’s ‘Theories

and Manifestoes of Contemporary Architecture’, p. 30).

Comparatively, Deleuze and Guattari assimilated the tree configuration

to that of books and roots. In the case of books, the tree configuration manifests

materially because books have axis and pages around (like trees have a trunk

and branches around), and meta-physically because books are reflections of reality

(since they reproduce reality they produce the double of it, thus progressing

always in binary shape). As Deleuze and Guattari pointed out of the ‘tree’

configuration: “This thought has never understood multiplicity: it requires

a supposedly strong sense of primordial unity in order to get two by a spiritual

method. And from the side of the object, according to the natural method, it

is dubious to pass directly from one to three, four or five, but on the condition

to have always a strong primordial unity, that is, of the axis that holds the

secondary roots”. (Rhizome, p.10).

The definition of the tree configuration is provided through

two theorems. On the one hand, Alexander wrote that “A collection of sets

forms a tree if and only if, for any two sets that belong to the collection,

either one is wholly contained in the other, or else they are wholly disjoint…

The enormity of this restriction is difficult to grasp. It is a little as though

the members of a family were not free to make friends outside the family, except

when the family as a whole made a friendship…” (Jencks, Op. Cit.

31). On the other hand, Guattari and Deleuze mentioned the ‘theorem of

friendship’ that may be related with that of the tree: ‘If in a

given society any two individuals have exactly a common friend there is an individual

that is friend to all the others”. (Rhizome, p. 27).

Alexander proposed the semi-lattice in order to establish a

critique of institutions and structures (mainly of suburban cities) organized

through the ‘tree’ configuration. Consequently, Guattari and Deleuze

extend on the critique to the concept of linearity that Modernity imposed: “The

modern methods, in their majority, are perfectly valid in order to proliferate

the series or to favor the development of multiplicity in one direction (for

instance lineal direction) meanwhile a unity of totalization affirms more in

another dimension, that of a circle or of a cycle.” (Rhizome, p.11). Moreover,

Guattari and Deleuze affirmed that circularity does not resolve the issue of

free connections. Hence they proposed the solution as the rhizome.

The multiple, the rhizome, may be found in vegetables with

multiple connections and even in the groups that animals like rats produce.

A den is a rhizome, a functional habitat that provides modalities of prevision,

displacement, evasion and capture. Furthermore, according to Guattari and Deleuze,

the rhizome works like a social device that denies language: “Rhizome

in itself has very diverse forms, from its superficial extension ramified in

all directions, until its concretions in bulbs and tubers...A rhizome does not

stop connecting semiotic chains, power organizations, junctures related to arts,

sciences and social struggles. A semiotic chain is a tubercle that joins diverse

acts, whether they are linguistic, perceptual, mimic or cogent: There is neither

language in itself nor universality of language.” (Rhizome, p.12-13).

Bertil Malmberg established the difference between the power of official languages

and the subversion of subterranean languages mentioning that the universality

of language proceeds as bulb, from a position of power in comparison to other

languages which evolution by ‘stems and subterranean flows, along fluvial

valleys, or railways, moving through oil spots’. (Bertil Malmberg is quoted

in Rhizome p. 13-14, from ‘The New Paths of Linguistic’, p. 72.

Mexico, Siglo XXI Ed.)

One of the most important characteristics of the rhizome is

that it has multiple entrances. Another important difference between the tree

configuration and the rhizome is that the last has no points or positions as

may be found in a structure, in a tree or in a root. There are not more that

lines that proliferate the whole in dynamism, always in connection to the external,

with “flat multiplicities of n dimensions that are a-significant and a-subjective”.

(Rizhome, p. 16). In some cases tubers, trees and roots may be found at the

end of the lines of a rhizome, but they do not have the primacy of central tubers

or trees. Moreover, Alexander’s definition of the semi-lattice establishes

a comparison with that of rhizome in the case of Deleuze and Guattari. For Alexander,

the semi-lattice axiom consists in the following definition: “A collection

of sets forms a semi-lattice if and only if, two overlapping sets belong to

the collection, then the set of elements common to both also belongs to the

collection”. (Jencks, p. 31).

Although criticized by its focus on methodology, it is important

to extend on Alexander’s work, because it opens the comprehension of reality

as an unlimited matrix of possibilities. For instance, Geoffrey Broadbent wrote

that “…according to Alexander, a tree based in 20 elements may contain

at the most 19 sub-ensembles of those 20 elements. On the other hand, a lattice,

also based on those 20 elements, may contain more than a million of sub-ensembles”.

(Broadbent, p. 273). Nevertheless, the difference between the concepts of Alexander

and those of Guattari and Deleuze is that the last focus in the internality

of the concept of a non-tree configuration, not specifically on the mathematical

possibilities.

According to Deleuze and Guattari, every rhizome is against

the excessively signification of the segments (for instance, the segments of

History). Hence, the lines of segmentation that rhizomes trace are stratified,

territorialized and organized. On the other hand, the lines are also signified

and attributed, but the focus is not specially on these processes. Furthermore,

the rhizome also provokes processes of de-territorialization and re-territorialization

that are relative; the rhizome constantly joins one to the other. (Rhizome,

p.17-18). The example of the orchid mimicking the wasp in order to accomplish

pollination is exemplary of the instance of territorialization and de-territorialization.

Deleuze and Guattari defined ‘plateau’ in order

to establish the definition of a field where the rhizomes are applied. This

definition may be extended to the field of concepts: “We call plateau

to every multiplicity connectable with others by subterranean superficial stems

in order to form and to extend a rhizome…Every plateau may be read everywhere

and may be related to everyone”. (Rhizome, p. 34).

In this sense, I hold the hypothesis that the field of History

(of Architecture) is a plateau formed by rhizomes. These rhizomes are lines

(not events, since events are points) of action that work together in a-parallel

trajectory, until selected by Historians in groups or associations in order

to establish which joint strategies these lines have in common. As the orchid

and the wasp, these elements have to wait until the moment of producing a common

rhizomatic association in order to succeed. In History, this lapse may take

decades or centuries to be produced. This plateau is a topography where concepts

run in different and even contradictory directions, since by definition any

connection may be established between two elements. Fixed points constituted

by discourse are constantly re-defined and even eliminated.

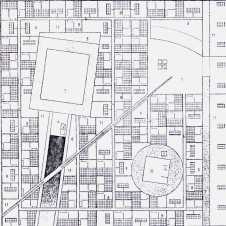

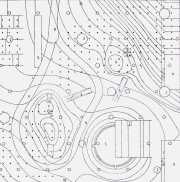

A)  |

B)  |

A) Alexander's diagrams on the city: Top, tree

configuration. Below, the semi-lattice. (Broadbent, p. 274). B) The Klein bottle,dDiagram

by Ben Van Berkel's UN studio, (Verstegen, p. 72).

3. Representations

of Diagrams: The ‘Tracing’ and the ‘Map’.

As aforementioned, the problem of representation arises for

both tree and rhizome. The architect has to represent for different purposes.

One of them is in the elaboration of

forms that embody rhizomatic connections

identified. Another is to structure the particularities of these connections.

As Hertzberger

points, the difficulty lies in representing the ideas (and concepts) adequately:

“A particular difficulty is faced by the architect…he cannot represent

his ideas in reality, but has to resort to representing them by means of symbols,

just as the composer only has his score with which to render what he hears.

While the composer may still more or less envisage what he has created by checking

to hear what his composition sounds like on the piano, the architect depends

entirely on the elusive world of drawings, which may never represent the space

he envisages in its entirety but may only represent separate aspects thereof

(and even so the drawings are difficult to read…This unsatisfactory state

of affairs is maintained and even aggravated by the fact that the drawing, irrespective

of the meaning it seeks to communicate, evokes an independent aesthetic image,

which threatens to overshadow the architect’s original intentions and

which may even be interpreted by the maker himself in a different sense than

initially foreseen)”. (Hertzberger, p.116).

Both tree and rhizome have a different representation. The

rhizome does not answer to structural or generative models which are mainly

principles capable of being reproducible until the infinite under the tree logic.

On the other hand, the logic of the tree is that of ‘tracing’ and

of reproduction and has as finality the copy of something that is given totally

finished from a structure that over-codifies and from an axis that supports.

This means that the logic of the representation of the tree is mainly based

on interpretations and significations. On the other hand, the rhizome produces

a map.

Deleuze and Guattari assimilated the ‘tree configuration’

to that of psychoanalysis, linguistics and structuralism, regenerations, reproductions,

returns, hydras, medusas, and even informatics: “Arborescent systems are

hierarchical systems that comprise centers of signification and subjectivation,

central automats and organized memories.”(Rhizome, p. 27). Furthermore,

Foucault (alluded by Deleuze) referred to the opposition between History and

structuralism when he wrote that “…the essential debate has not

mainly to do with structuralism as such, but with the existence of models and

realities denominated structures, as with the position and the statute that

correspond to the individual in dimensions that seemingly are not structured.

So, as History is opposed directly to structure, it may be thought that the

subject conserves a sense of constituent, agglomerated, unifying activity. But

it does not happen the same when the ‘epochs’ of historic formations

as multiplicities are considered. Those escape the realm of the subject and

of the structure as well.”(Foucault, p. 40-41). For Foucault, the ethic

of Power forbids the tracing of a structure in History, since this tracing derives

in interested interpretation.

(The field of History as a non-homogeneous plateau, is the

result of post-structuralism in the writings of authors like Deleuze; Foucault,

Lyotard, Baudrillard, alluded in Josep Maria Montaner’s book ‘Architecture

and Critique’: ‘We have entered into a new period in which cultural

multiplicity prevails and in which the post-modern doubt has conduced to new

scientific interpretations based on the concept of a universe in non-equilibrium.

Such a concept is expressed in fractal geometries under the theory of chaos.

Methods of thinking increase their critique and justify discontinuous, fragmentary

and provisional interpretations based on the emphasis of transformation and

difference. Scientific and philosophical activity are obliged to surrender their

pretensions of neutrality and objectivity to the will of universal knowledge

and to its project of a unified science and totalizing philosophy. Post-structuralism

in architecture appears under the condition of perpetual crisis, in the lost

of faith in great interpretations and in doubts on the capacity of linguistic

to explain architecture' . (Montaner; Arquitectura y Crítica, GG Básicos;

Barcelona, 1999; pg. 90).

Let us elaborate in the example of psychoanalysis, which Deleuze

and Guattari identified with the formation and consolidation of the tree as

validation of organizations. In order to interpret pathologies in the complex

‘net’ that human brain is (which understood in global terms is the

map of the potential of humankind) psychoanalysts proceeds coding and assigning

interpretations arbitrarily, thus precluding the understanding of political,

material and proceedings that cannot be explained solely with interested or

discursive configurations, such as those of the tracing and the tree. Tracing

over the map of human mind is like trying to find figures over the tomography

of a patient and then using the figures as interpretations of pathologies. (Non-physiological)

explanations are to be found neither in the tomography nor in the interior of

the person’s mind itself but on the outside, in his relations and experiences.

The map cannot be understood if not taken as a global instrument

associated with lines of action and (social as well as geographical) ruptures.

The map is a productive device that registers different changing temperatures

of social stability and instability. The tracing and dismembering of the map

into singular layers cannot but preclude the understanding of the place as a

globality. In this sense, Deleuze and Guattari depicted the ‘tracing’

as an instrument that lacks the operativity of the ‘map’.

The comparison of maps and the definition of globality of Deleuze

and Guattari establish a link with the 1905’s theory of Planning called

‘Survey before Plan’ by the Scot Patrick Geddes (theory described

by planner Peter Hall in his book ‘Cities of Tomorrow’). The point

is the outstanding similitude in the layering and the understanding of the relationship

among intertwined phenomena as described in the definition of rhizome and plateau:

“Planning must start, for Geddes, with a survey of the resources of such

a natural region, of the human responses to it, and of the resulting complexities

of the cultural landscape…For this great work, Geddes constantly argued,

the planner’s ordinary maps were useless: you must start with the great

globe…”(Hall, p. 142). Geddes’s planning theory extends to

the approach of rhizomes in fields called plateaus that have relationships with

other plateaus (thus implying the relationship among History, Sciences, Planning,

etc.) Geddes vision is truly ecological and refers to processes of symbiosis.

The planner assimilates natural and social phenomena through analysis (the survey)

and establishes a relationship with other intertwined plateaus. The similitude

with Deleuze and Guattari’s theory of rhizomes is relevant for Planning.

(Urban and regional planner Edward Soja, in his essay ‘Restructuring

the Industrial Capitalist City, in the book TransUrbanism, describes the relationship

that the architect must have with the different scales. A direct nexus may be

established with the rhizomatic approach and the work on different scales that

characterized Patrick Geddes: ‘The…disagreement arises from the

different scales and concepts of urbanism that exist within architecture versus

those in geography and planning…The core architectural view…consists

of streets, road and a built environment located within a vaguely defined 'urban

cloud'. In this vision, the city becomes a collection of separate cells with

built environments compacted together to form an urban mass. This view is radically

different from the larger-scale spatial or regional vision of the city as an

expansive urban system of movements and flows…and people living not just

in built environments but in constructed geographies characterized by different

patterns of income, employment, educational levels, ethnic and racial cultures,

housing and job densities, etc... These constructed geographies get lost when

the city is reduced entirely to a collection of built forms. As a result, architects

tend to see planning the city as their exclusive domain, as specialists in built

form, or else they dissociate themselves entirely from the planning process,

seen it only as imposing constraints on their creativity. The city that the

geographer looks at is much more than the built environment. What's being planned

from the geographer's point of view is a very different kind of city. The emphasis

is not on the built environment per se but on a more variegated and larger scale

social environment…That is, …(try ) …to think on multiple

scales- local, human and Regional -then to even larger regional, national supra

national and global scales. In the sense, the architect is being encouraged

to think an little bit more like the geographer, and specially to think regionally...).

Edward Soja, in ‘Restructuring the Industrial Capitalist City; op.cit.

pg. 90).

On the other hand, the opposed model of work that relates to

‘tracings’ has been criticized by Harvey for whom this method opposes

complex reality: ‘Urban planning, which has always been dominated by the

primal work element of the drafting board and particularly by the process of

copying draws from the maps (a deceiving instrument as no other), was completely

immerse in the details concerning the human spatial organization on the terrain.

In order to take a decision on a concrete lot, the urban planner…painted

it in red or green on a planning map, according to his own intuitive evaluation

of the spatial form…Webber…considers vital that the planner relinquishes

“the deeply rooted doctrine that seeks its method in models extracted

from maps when, on the other hand, it is hidden inside extremely complex social

organizations”.’ (Harvey, in pg. 19, alludes M. Webber in ‘Order

in Diversity: Community without Propinquity’ in Wingo, L., comp., Cities

and Space: The Future Use Of Urban Land (Baltimore, 1963, pg. 54).

Alejandro Zaera Polo complements the definition of tracings

and maps in reference to the work of Rem

Koolhaas and OMA in ‘Notes for a Topographic Survey’ (Croquis

# 53, 1997): “Tracing is the term used by Deleuze and Guattari in order

to classify any ‘representation’ of reality operating as an abstract

system of codification with a tendency to establish rules, measures, or ‘compositions’.

‘Tracing’ opposes the ‘map’, which is an instrument

of contact with reality, always in perpetual modification, meant for experimentation.

‘Tracing’ is a tool for the determination of ‘competences’,

whereas the ‘map’ is an arm of ‘performances’. The almost

purely graphical approach which characterizes the work of (Zaha) Hadid and (Elia)

Zenghelis, is almost immediately identifiable with ‘tracing’ as

a formal abstraction of reality”. (Croquis 53, p.35).

Guattari and Deleuze wrote that the map “is open, connectable

in all its dimensions, demountable, reversible, and capable of receiving constant

modifications. It may be broken, inverted, adapted to mountains of any nature,

and commenced by an individual, group or social association”. (Rhizome,

p. 22). We may perform a tracing over a map, but the result is that the tracing

has translated the map, transforming the rhizome into roots: It has organized,

stabilized and neutralized the rhizome. The tracing only reproduces: “That

is why it is so harmful. It injects redundancies and propagates them. What the

tracing reproduce of the rhizome is just the mires, the blockades, the germens

of the axis or the points of structure…When a rhizome is intercepted,

arborified, it is over, nothing happens with its desire; because it is always

by desire that the rhizome moves and produces… the rhizome operates on

desire by external and productive impulses”. (Rhizome; p.23-24). According

to Deleuze, what proceeds from the outside are forces; Deleuze places this outside

even further than any form of exteriority. “At the same time, not only

singularities of forces but singularities of resistance exist as well. The last

are capable of modifying and permuting those relationships, changing the instable

diagram”. (Foucault, p. 157).

Philosopher Christine

Buci-Glucksmann in “From the Cartographical View to the Virtual”

wrote that “the map is…a space that is open to multiple entrances,

a ‘plateau’ where the gaze becomes nomadic.” For Buci-Glucksmann,

the map is immediately both visible and readable: “The map seizes the

real, masters it, and allows a glimpse of an unconscious quality of vision with

its folding and unfolding, within a weightless plane. A map takes possession

of the limits and the borders of the unlimited… An abstraction such as

the virtual presupposes a mental image of the world and an abstract machine

made of lines and of possibilities enabling one to ‘read a map’,

as we say. This involves a complex reading, because one needs to project oneself

outside of oneself, to forget one’s own position, in order to explore

this cartography in rhizomes… From now on, the cartogram of contemporary

art is endless, since the map is the interface of the world, as in Archizoom’s

‘No-Stop City’ (1969). And it is precisely this world-making quality

of the map that generates all its paradoxes and its multiple logics. Since,

however utopic it may be, the map may also become a highly effective machine

of power. With the maps kept secret by totalitarian regimes, targeted bombings

of sites, indeed of populations, the map truly is ‘a portrait’,

an image ‘in meaning and in representation”.

Deleuze wrote in ‘Bergsonism’ that virtuality (of

the maps, in this case) is ‘…the subjective, or the duration, …the

virtual. More precisely, the virtual, as actualization, cannot be separated

from the movement of its actualization since actualization is fulfilled by differentiation,

by divergent lines, and creates by its own movement many other differences of

nature’ (Deleuze, Bergsonism’, pg. 41). In this sense, the map is

virtual, it actualizes itself. On the other hand, the tracing is defined by

generating actualizations only through discourse.

Deleuze continues that “…from a certain point of

view, the possible is contrary to the real, it opposes the real; furthermore

the virtual opposes the actual, what is absolutely different…The possible

does not have reality (although it may have an actuality; inversely, the virtual

is not actual, nevertheless it has a reality). The best formula to define the

states of virtuality is that of Proust: ‘ Real without being actual, ideal

without being abstract’…And since not all possible fulfills, fulfillment

implies a limitation by which certain possibilities are considered rejected

or prohibited, meanwhile other ‘pass’ to the real. The virtual,

on the other hand, does not have to fulfill, only actualize and actualization

yet does not have as rules similarity and limitation, but difference or divergence

and creation…since the virtual cannot proceed by elimination or limitation

to actualize, but it must create its own lines of actualization in positive

acts…In summary, the characteristic of the virtual is to exist in such

a way that it is only actualized by difference: it is forced to difference,

to create lines of difference in order to fulfill actualization’. (Deleuze,

Bergsonism; pg. 101)

Castoriadis coincides with Buci-Glucksman: producing a map

requires projecting out of the own discourse. Furthermore, Castoriadis establishes

a critique to the repetition of the tracing scheme: ‘…what characterizes

each process of metabolizing determined by the encounter between the psychic

space and the space external to the psyche is defined by the specificity of

the relational model imposed to the elements of the represented. On the other

hand, this model is the trace of the representative’s own structural scheme’.

(Castoriadis, p. 40)

Represented in ‘tracings’ or in ‘maps’,

both tree and rhizome reproduce the image of the world (imago mundi). The only

possibility to escape to the image of the world that theory has proposed is

assimilating it with a box of tools, avoiding the discursive practice. As Miguel

Morey wrote in the prologue to the Spanish edition of ‘Foucault’:

“As a ‘box of tools’, the book’s connection with a domain

of exteriority is what gives the book and theory their specific importance.

At the same time they surrender their pretensions of setting, proposing or imposing

an imago mundi; the writing, the theory, the book are tools altogether with

other tools, standing all in order to be proved exteriorly to themselves and

in multiple, local and plural connection with other books, with other theories,

with other writings.” (Foucault, p. 13). Foucault established a critique

to the systems and referred theory as an instrument for the relations of power

and the struggles around it. He compromised Historic reflection (in certain

dimensions) in the search of such a task. (Foucault p. 12).

In summary, the map is the mimesis of the world, an image of

the world, an ‘imago mundi’. Nevertheless, it is also a holistic

and political device for representation. The maps of capitalism are indeed different

from the maps of socialism. They represent different positions and have different

intentions. The maps of performance are also political; they cannot take away

themselves from the modes of production. Furthermore, Christine Buci-Glucksmann

establishes categories between the map and the diagram. She wrote that “…the

diagram is already in itself a map or an overlay of maps, that allows one to

explore movements…and virtual volumes…The diagram explores continuous

space, the constructed, within an abstract figurative which initiates an experience

of thought, through its allusive and schematic structure…(in) a kind of

Leibnizian reasoning, that one rediscovers in the new connections made between

the numeric continuousness and the morphogenesis that are so characteristic

of architectures of the virtual. Seeing is to (construct, build) and to know,

to link… systems, arrangements made of lines, of forces and of vectorial

points, as in Paul Klee’s schemas, where the arrows are forces. The map

combines the two space-times distinguished by Boulez and developed by Deleuze

and Guattari in ‘Mille Plateaus’.”

4. The Materiality of Rhizomes

at the Architectonic and Urban Level

Architectural rhizomes find an example in the Agadir Congress

Center of Rem Koolhaas, which is in Zaera Polo’s essay ‘OMA 1986-1991.

Notes for a Topographic Survey’ probably ‘…the most astonishing

example of this material corporeality, of the connectivity of smooth space.

No more segmentation between spaces, no more homogeneity: a continuous variation

of form through space, the generation of a vectorial, directional and anisotropic

space. Agadir is a differential space rather than an articulation of homogeneities.

From the simple elimination of the structural grid, the setting of spatial or

metric references disappears and with them the possibility of a formal codification.

Space and material are treated in Agadir like dynamic flows rather than stable

forms. (Croquis #53, p. 45). Zaera Polo explains that topological, or projective

geometries substitute Euclidian or metric geometries in an epistemological difference;

The Agadir Congress centre is a ‘…topograph(y) where measure and

proportion, the basic instruments of classical architecture, are replaced by

fundamentally topological relationships, geometries of connections, adjacencies

or distances instead of measurements, magnitudes or properties’. (Croquis

#53, pg. 40).

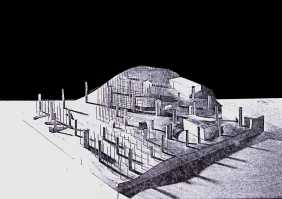

The Agadir Congress Centre is a hotel and congress palace designed

in 1990 by Koolhaas in Morocco. It constitutes a project based on geology and

topology, since it does not depart from top-down typology as direct re-elaboration.

On the other hand, it does not proceed strictly from information as the bottom-up

designs of FOA. Agadir’s concept establishes and promotes spatial connections

that derive in topological and geometrical super-impositions.

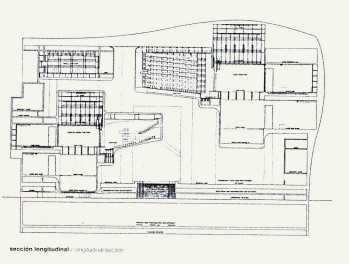

Agadir’s section reveals what Colin Rowe denominated

‘phenomenologic transparency’, a section working as façade

and establishing direct visual relationships with the content of the building.

The structure does not modulate the non-Cartesian space which is truly proto-functional

(it is functional but redefines the temporality of function through durations

more than through standard measure). Structural elements are not posed as indexes

(as coded information in gridded space), but as a truly topography or cartography,