Heroes

And Mythology

If

you happen to be the perfect home

maker living in New York City who

loves baseball, then it hasn't

been a very good couple of weeks

for you: Martha Stewart was

indicted for obstructing justice,

the New York Times printed

fabricated stories, and Sammy

Sosa got caught cheating at the

plate. These are giants of their

industries, icons to countless

millions, wealthy beyond

reason...and they let their

followers down. As it turns out,

they are as flawed as the rest of

us, and probably even more

vulnerable to internal demons. So

what else is new?

Mankind

has been engaged in hero-worship

since time immemorial, and from

beginning to end it's been a load

of rubbish. The ancient Greeks at

least had the good sense to make

their champions mythical, so as

to bestow them with attributes

and ideals that wouldn't be

compromised by mortal weakness.

Anything more is illogical and

far less instructive, and the

Greeks were nothing if not

instructive. The lesson this

teaches is that ideals should be

embraced but not assigned, at

least not in a mortal context.

What is gained when heroes fall

far short of expectations,

resulting in disappointment,

disallusionment and discust? Who

does that benefit, and towards

what end? It suggests that we're

frail, insecure little creatures

who find comfort and refuge in

the accomplishments of those we

perceive to be greater than

ourselves; we live vicariously

through them, hoping to gain

insight and strength from their

example, consequently setting

ourselves up for a fall when they

stumble. It says volumes about

our need for

bigger-than-life heroes to

provide answers to the questions

that we ourselves not only can't

answer, but don't even know how

to ask. And it says we're looking

for these answers in the wrong

places.

None

of this should come as a

surprise. In an era of relativism

that values celebrity over

substance, where cultural

revisionism keeps moving the goal

posts, and "experts" on

everything babble on and on

without any more of a clue about

anything than anyone else, it's

no wonder we're confused about

whom, and what, to believe.

Absolutes no longer seem so

absolute, nor heroes so heroic.

I

interpret these events as the

metastisizing of a malignant

value system, whereby our heroes

are turned against us. Our need

for guidance is tempered by a

desire for cultural convenience

and metaphysical expedience, so

as not to upset our worship of

the superficial and

inconsequential. We want to be

fulfilled, but don't want to do

the heavy lifting required, so we

ask others to do the work for us.

We project unto them ideals to

which we ourselves don't aspire,

then are dismayed when they turn

out to be as non-ideological as

the rest of us. Not only are our

hopes and trust dashed as a

result, but the very ideals

themselves seem diminished.

We

require more of our heroes than

of ourselves, and therein lies

the problem. Those we elevate

above all others should be every

bit as much a reflection of who

we actually are as who we want to

be. But that's not the case. The

differential in American society

now is such that as long as our

icons are excellent, then the

rest of us can embrace mendacity

and mediocrity, because that's

much easier. But when heroes fail

under the weight of an

unrealistic load, rather than

blame them, we should blame

ourselves for being hypocrites.

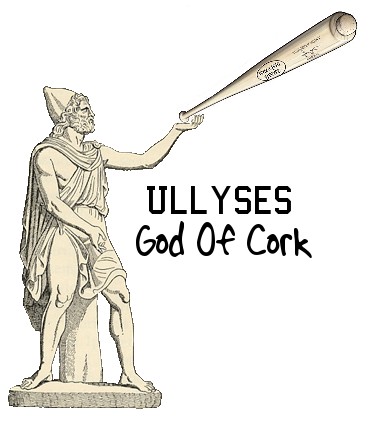

The

Greeks avoided this trap by

taking human frailty out of the

equation, thereby assuring that

the representatives of their

ideals would remain steadfast,

unswerving and absolute. This

would appear to be a much better

way of teaching classical truths,

while keeping heroes honest.

After all, did you ever hear of

Ullyses getting caught corking

his bat...?

|