The Mongols and

Timurids

The

Mongols appear in history at the end of the twelfth century. In the

opening decades of the thirteenth century, Chinggis (or Genghis) Khan

(1167-1227) unified the Mongol tribes on the steppe lands to the north of China and thereafter Mongol armies

invaded China and the Middle East. In 1220 Transoxania was conquered and

in the 1220s roaming Mongol armies spread devastation in the Middle East

as far west as the Caucasus. Mongol occupation of the Middle East to the

south and west of the Oxus began in the 1250s. In 1256 they occupied

northern Iran and in 1258 captured Baghdad and murdered the city's last

Abbasid caliph. In 1260s the Mongols were defeated by a Mamluk army from

Egypt at Ayn

the steppe lands to the north of China and thereafter Mongol armies

invaded China and the Middle East. In 1220 Transoxania was conquered and

in the 1220s roaming Mongol armies spread devastation in the Middle East

as far west as the Caucasus. Mongol occupation of the Middle East to the

south and west of the Oxus began in the 1250s. In 1256 they occupied

northern Iran and in 1258 captured Baghdad and murdered the city's last

Abbasid caliph. In 1260s the Mongols were defeated by a Mamluk army from

Egypt at Ayn  Jalut in

Palestine, which prevented their further spread westwards. They

established an Ilkhanate, a territorial principality that included Iran,

Iraq, and parts of Anatolia and the Caucasus. The Ilkhan Ghazan (Ilkhan

means "subordinate Khan") became a Muslim and from then on

Islam was the official religion of the principality. Jalut in

Palestine, which prevented their further spread westwards. They

established an Ilkhanate, a territorial principality that included Iran,

Iraq, and parts of Anatolia and the Caucasus. The Ilkhan Ghazan (Ilkhan

means "subordinate Khan") became a Muslim and from then on

Islam was the official religion of the principality.

Timur (also known in the West as Tamerlane or Tamburlaine),

who had begun his career as a rustler and brigand in in Transoxania,

made a determined attempt to reconstitute the Mongol world empire (two

of his wives were descended from Chinggis Khan). The empire he

ultimately created consisted essentially of Persia, Iraq, Khurasan, and

Transoxania, but he also campaigned in Syria, Anatolia, the Caucasus , Russia, Afghanistan, and India and, at the time of his death

in 1405, was preparing to invade China.

Caucasus , Russia, Afghanistan, and India and, at the time of his death

in 1405, was preparing to invade China.

As has been said, in the early centuries of Islam there were no royal

workshops as such, and craft workers were hired and brought together for

specific projects. However, libraries seem to have become important

centres for the sponsorship of the arts in  the

period after the Mongol invasion, under the Ilkhans and their successors

in Iran. It is possible that the source of inspiration for this

institutional innovation may have come from the Chinese academies of

history and painting with which the Mongols had become familiar in the

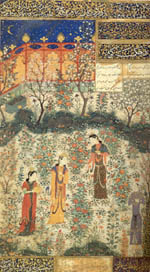

east. One broad consequence of this development is that illustrated

books, and those who worked on books, on their calligraphy, their page

layout, their gilding, and the designs of the leather bindings, became

of central importance for developments in other fields of art and

architecture. Thus under the Timurids designs that were first developed

for books provided templates for work done in the

period after the Mongol invasion, under the Ilkhans and their successors

in Iran. It is possible that the source of inspiration for this

institutional innovation may have come from the Chinese academies of

history and painting with which the Mongols had become familiar in the

east. One broad consequence of this development is that illustrated

books, and those who worked on books, on their calligraphy, their page

layout, their gilding, and the designs of the leather bindings, became

of central importance for developments in other fields of art and

architecture. Thus under the Timurids designs that were first developed

for books provided templates for work done in other media - in stone-cutting, tiles, ceramics, mother-of pearl, saddle work,

and tent-making. Chinese influence may lie behind the restrained and

sombre palette seen not only in the illustrations to books like the

"Demotte" Shahnama, but also in the dark colours

favoured in the Iranian Sultanabad and Lajvardina ceramic wares

produced in this period. The Mongol elite and in particular the Ilkhan

Ghazan took a great interest in the history of their people as well as

of the wider world that they had plans to conquer. this taste, which

resulted in the production of illustrated histories, continued in the

Iranian and Turkish cultural area under the patronage of such dynasties

as the Timurids and the Ottomans.

other media - in stone-cutting, tiles, ceramics, mother-of pearl, saddle work,

and tent-making. Chinese influence may lie behind the restrained and

sombre palette seen not only in the illustrations to books like the

"Demotte" Shahnama, but also in the dark colours

favoured in the Iranian Sultanabad and Lajvardina ceramic wares

produced in this period. The Mongol elite and in particular the Ilkhan

Ghazan took a great interest in the history of their people as well as

of the wider world that they had plans to conquer. this taste, which

resulted in the production of illustrated histories, continued in the

Iranian and Turkish cultural area under the patronage of such dynasties

as the Timurids and the Ottomans.

Ghazan

was credited by his vizier, Rashid al-Din, with a range of craft skills:

the Ilkhan was reputed to be expert in woodwork and goldsmithery, he

painted, and painted, and he made saddles, bridles, and spurs. The

notion that a ruler, or indeed any leading member of the military elite,

should possess some artistic or artisanal skill seems to have been widespread

among the Mongols and Turks. Ghazan

was credited by his vizier, Rashid al-Din, with a range of craft skills:

the Ilkhan was reputed to be expert in woodwork and goldsmithery, he

painted, and painted, and he made saddles, bridles, and spurs. The

notion that a ruler, or indeed any leading member of the military elite,

should possess some artistic or artisanal skill seems to have been widespread

among the Mongols and Turks.

Timur's son and successors, Shah Rukh, seems to have

regarded Ghazan as his exemplar. His patronage and that of his wife,

Gawharshad, were conceived of in largely religious terms. Here it is

worth nothing that women played a much more important role both in

politics and in art patronage in the Ilkhanid and Timurid empires than

they had done under earlier Arab and Turkish regimes. Timur's chief

wife, Saray Mulk Khanum, had built a madrasa opposite the Friday

Mosque in Samarqand. Another queen, Tuman-agha, built a Sufi khanqa

(foundation). Gawharshad commissioned a mosque-madrasa complex in

Herat, as well as paying for restoration work or improvements on

existing religious monuments.

Baysunqur, the son of Shah Rukh, who predeceased his father

in 1434, was an expert calligrapher and bookbinder who also painted and

wrote poetry. However, what makes him particularly interesting to

students of Islamic artistic patronage is his establishment of what was

effectively a design workshop in 1420s. We know an unusual amount about

this workshop because of an arzadasht, or petition document; this

was a sort of progress report by the head of the establishment that was

sent to Baysunqur around 1429. The workshop or kitabkhana

(literally, a store for keeping books, but in practice a library and

workshop for the production of manuscripts and other artefacts) employed

forty calligraphers, plus designers, painters, bookbinders,

stone-cutters, and workers on luxury tents. Some twenty-two projects in hand

were reported on. Thus a great deal of artistic patronage was channelled

through and overseen by a princely "library".

Not all

the great patrons of the Timurid period were of royal blood. Mir Ali

Shir Navai (1441-1501) was the courtier and cup companion of Husayn

Bayqara, the Timurid ruler in Herat from 1470 to 1506. Navai is chiefly

famous today as the greatest poet to write in Chagatay Turkish. He was

also a wealthy man and as such enormously important as a patron of

architecture and art. He spent great sums of money perpetuating his

memory through buildings; according to him: "Whoever builds a

structure that is destined [to remain], when [his] name is inscribed

therein,/For as long as the structure lasts, that name will be on the

lips pf the people." Navai was also a patron of the arts of the

book. Bihzad, who was to become widely recognized as the greatest

miniature-painter of his age, was given a start in his career by being

employed as head of Navai's library. Not all

the great patrons of the Timurid period were of royal blood. Mir Ali

Shir Navai (1441-1501) was the courtier and cup companion of Husayn

Bayqara, the Timurid ruler in Herat from 1470 to 1506. Navai is chiefly

famous today as the greatest poet to write in Chagatay Turkish. He was

also a wealthy man and as such enormously important as a patron of

architecture and art. He spent great sums of money perpetuating his

memory through buildings; according to him: "Whoever builds a

structure that is destined [to remain], when [his] name is inscribed

therein,/For as long as the structure lasts, that name will be on the

lips pf the people." Navai was also a patron of the arts of the

book. Bihzad, who was to become widely recognized as the greatest

miniature-painter of his age, was given a start in his career by being

employed as head of Navai's library.

It is in part thanks to Baburnama (The Book of

Babur), the memories of the Timurid prince Zahir al-Din Babur, that we

know about the activities of Navai and the Timurid artist-princes of Samarqand and Herat. Briefly ruler of Samarqand and

later of Kabul, Babur ended up as ruler of north-west India from 1526 to

1530, where he founded the Mughal empire. Babur's memories reveal him to

have been extremely aware of the beauty of landscape. His visual

sensibility was shaped by his familiarity with Persian painting: When he

saw a striking arrangement of apples and leaves on a particular tree, he

commented that "if painters exerted every effort they wouldn't have

been able to depict such a thing." Clearly, he was a connoisseur

and critic of painting, but perhaps also a rather native one. Thus, in

commenting on the art of Bihzad, he confined himself to remarking that

" He painted extremely delicately, but he made the faces of

beardless people badly by drawing the double chin too big. He drew the

faces of bearded people quite well."

artist-princes of Samarqand and Herat. Briefly ruler of Samarqand and

later of Kabul, Babur ended up as ruler of north-west India from 1526 to

1530, where he founded the Mughal empire. Babur's memories reveal him to

have been extremely aware of the beauty of landscape. His visual

sensibility was shaped by his familiarity with Persian painting: When he

saw a striking arrangement of apples and leaves on a particular tree, he

commented that "if painters exerted every effort they wouldn't have

been able to depict such a thing." Clearly, he was a connoisseur

and critic of painting, but perhaps also a rather native one. Thus, in

commenting on the art of Bihzad, he confined himself to remarking that

" He painted extremely delicately, but he made the faces of

beardless people badly by drawing the double chin too big. He drew the

faces of bearded people quite well."

Islamic Art

Robert

Irwin

|