| Chapter 4 |

| What Does Copyright Infringement Mean? |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. |

|

| Image provided by the Library of Congress |

| Viacom sues Google - $1 billion for copyright infringement! A Kazaa user is liable for copyright infringement - $222,000 in damages! U.S. cracks multimillion-dollar piracy ring! |

| These are certainly eye-catching (and mind-numbing) figures. In certain situations, copyright law can be a powerful way to protect your work. However, we should note that these, like many flashy news reports, don't reflect the risks and realities of copyright infringement for the average individual. In fact, front-page headlines and over-reaching copyright claims may distort what copyright law actually does. Unclear and inaccurate perceptions of copyright law can deter you and me from making and using creative works. This hinders public learning and is exactly the opposite effect that copyright law is supposed to have. |

| In this chapter we discuss what copyright infringement is and how it fits within the overall goal of copyright law. In particular, we will cover when someone infringes a copyright. Our goal is to clear up some of the confusion surrounding copyright infringement. |

| Part I. What Isn't Copyright Infringement? |

| As we discussed in chapter 1, a copyright grants its owner the exclusive right to do six things with respect to the copyrighted work (there are some additional rights for works of visual arts, but we'll ignore those for now). Specifically, only the copyright owner can (1) make copies, (2) make derivative works, (3) publicly distribute the work, (4) publicly perform the work, (5) publicly display the work, or (6) publicly perform a sound recording by means of a digital audio transmission. The copyright owner can also authorize others to exercise these rights through a licensing agreement, as we discussed in chapter 3. However, to understand copyright infringment, the next point is critical: COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT ONLY DEALS WITH THESE SIX RIGHTS. If another's use is not covered by one of these specific rights, then there is no copyright infringement. To illustrate, let's return to Annie Author and her sucessful novels. |

| You probably see why copyright infringement can be such a confusing subject. To be frank, the copyright law is terribly written and causes a lot of misunderstandings. However, there are other issues which may actually inflict greater harm than a poorly worded statute. As I mentioned at the beginning of the chapter, many individuals and companies greatly exaggerate and overstate their copyright claims. Here are a couple of outrageous examples: |

| First, we have Major League Baseball. Peppercornconsider was considerate enough to post their copyright warning on YouTube. |

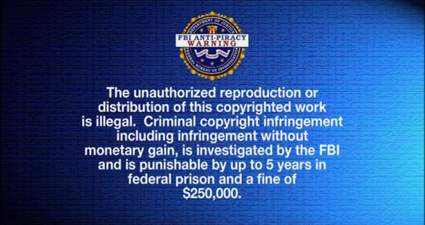

| Did you catch that last part of the warning? Here it is in print: �This copyrighted telecast is presented by authority of Sterling Mets. It may not be reproduced or retransmitted in any form, and the accounts and descriptions of this game may not be disseminated without the express written consent of Sterling Mets.� Now, to be fair, Sterling Mets does have a legitimate copyright in the broadcast. It would be infringment to wholesale copy the broadcast and sell it to others. The problem is they are claiming more than that. For example, take the phrase "descriptions of this game may not be disseminated without express written consent." Essentially, they are claiming that I need written permission to discuss how my favorite player did in the game last night. As one critic asked "Do I really need the express written consent . . . in order to legally tell you that Barry Bonds walked on four pitches in the fifth inning?" In addition, the first part of the warning is entirely incorrect. Using a small portion won't be copyright infringement - you CAN do that (the "de minimus" test, which we discussed in chapter 2, covers this situation). Even if you reproduce a substantial portion of the telecast, fair use allows you to do so in any form - subject only to the limits provided by the fair use doctrine. Now this particular example may not seem like a big deal. Patrick Ross, executive director of the Copyright Alliance (the Copyright Alliance members include the Motion Picture Association of America, NBC Universal and the National Music Publishers� Association, as well as Major League Baseball and the NFL) stated �The first thing I�d like to know is, what is the demonstrated harm?� The real harm occurs when companies repeatedly push these over-reaching warnings on ordinary consumers. These unfounded claims push the public's perception of copyright law far away from what the law actually means. What falls through the cracks? The valuable contributions of ordinary people - in other words, you and I. Similar scare tactics have been used by hollywood for quite some time. Next time you watch a DVD or VHS movie, take a quick look at the FBI warning that appears at the start. |

|

| Several groups in the music industry are doing the same thing. They formed "Music United" and wrote a website that repeats the warning and then ominously adds "Don�t you have a better way to spend five years and $250,000?" Seems scary to me - five years and $250k is a hefty price to pay. But they are not telling you two things. First, criminal copyright infringment involves more than making an unauthorized reproduction or distribution of the work. To qualify for criminal sanctions, the law tacks on several requirements that aren't there for normal (civil) copyright infringement. For example, criminal copyright infringement must be willfull - i.e. done with the intent to infringe. A good faith belief that your use is fair or otherwise not infringing will shield you from the criminal penalty. The U.S. Department of Justice wrote "criminal sanctions continue to apply only to certain types of infringement�generally when the infringement is particularly serious, the infringer knows the infringement is wrong, or the type of case renders civil enforcement by individual copyright owners especially difficult." These, along with other requirements for criminal sanctions, make it very unlikely that an ordinary person, such as you and I, will ever be guilty of criminal copyright infringment. Essentially, they are using the possibility (and not the probability) of criminal sanctions as a scare tactic to bully and intimidate consumers. Second, they neglect to inform you that fair use of the work is permitted by law. In other words, when the use is fair the unauthorized reporduction or distribution of the copyrighted work is NOT illegal. But it does not serve their purposes to remind you of your rights. |

| I bring up this point not to encourage copyright infringement - copyright infringment is bad. But scare tactics inaccurately reflect the realities of copyright law and cause more harm than they prevent. These warnings are designed to deter serious infringers but they also deter ordinary people from using the work in non-infringing ways. This misuse of copyright is causing you and I to miss out on some of the benefits of copyright (i.e. learning and enrichment) but still make us bear the burden of the copyright monopoly. |

|

| Let's assume Annie has published a novel entitled "Piracy On The Open Net." The book is an instant success and attracts the attention of both readers and competitiors. Onto the scene comes Wendy Wordsmith, Annie's artistic archrival. As you can see from her picture, you don't mess with Wendy. Looking at Annie's overnight success, she decides to enter the market niche and publish her own works. Now, Annie's copyright gives her the exclusive right to make copies - so Wendy can't photocopy her book or borrow portions of her prose (absent Fair Use, of course). The copyright also protects derivative works - so Wendy can't make "Piracy On The Open Net, The Movie" without Annie's permission. Wendy cannot publicly distribute "Piracy" (absent the First Sale doctrine) nor can she publicly perform or display the book. All these activities are covered by the copyright. We'll come back to what activites constitute infringment in a little bit - let's quickly look at what is not copyright infringement. There are several things that Wendy CAN do with Annie's novel that would not be copyright infringement. For example, she could use the ideas embodied in "Piracy" to write her own competing book. Since copyright protection does not cover ideas but only the expression of ideas, Wendy is free to use them - even to create a competing novel. There are also limitations and unique qualifications found in the exclusive rights themselves - i.e. a "copy" for the purposes of copyright infringement may be different than how the word "copy" (either as a noun or a verb) is used by you or I. In addition, copyright law is full of specific exemptions that apply only to certain situations. For example, teachers and students have explicit premission to display a work as part of their classroom experience. Religious entities enjoy a similar right with respect to religious works. If your are part of a non-profit organization, I suggest visiting your local copyright attorney to see if you fit within these specific provisions. |

| Photo provided by Old Shoe Woman This author is named Sheila Rice and is probably a very nice person. |

| Part II. What Is Copyright Infringement? |

| With that in mind, let's turn our attention back to the news clippings at the top of the page. Those are huge numbers associated with copyright infringement and can scare people away from using a creative work. But let's look a little closer at the actual consequences of copyright infringement so that we have a more accurate idea of the risks and remedies available to a copyright holder. |

| Earlier, when discussing Annie and Wendy, we touched on some examples of what would constitute copyright infringement, such as copying the book, or using the book to make an unauthorized derivative work (like a movie based on the book). While simple examples make good illustrations, they lose sight of subtle, but important details. To help us better understand what constitutes copyright infringement, let's take a closer look at the legal standard for copyright infringement. |

| First, a copyright owner must prove she has a valid copyright. If there is no valid copyright in the work, than there simply cannot be copyright infringement. Second, the copyright owner must prove the alleged infringer violated one of the exclusive rights. At this point I want to point out that a copyright protects the work only against actual copying. If you write a song and I somehow happen to write the exact same song two days later, there is simply no copyright infringement. Copyright law calls this "independant creation." If I can show that I came up with the song without using your work then I will not be liable for copyright infringement. In most copyright cases, it is difficult for the copyright owner to show direct copying. So instead she will have to rely on circumstantial evidence to show her work was probably copied. To do this, the copyright owner must show that the alleged infringer had access to her work and that the allegedly infringing work is substantially similar to the original. But that is not all. Even if the alleged infringer had access to the work, and the two works are similar, there is still another step to take. Earlier, we discussed how certain things, such as facts or ideas, are not copyrightable. The next step in the analysis filters out all the unprotectable elements. If the two works have the same title, we ignore the title, since titles are not copyrightable. We also ignore any ideas, facts, processes, etc. that may be common between the works. After that we see what's left to determine if the exclusive right has been violated. Now, it is an easy case if the entire work was copied (for example, if I photocopied Annie's book). But what if I changed a word or two? As you probably guessed, that won't save me. On the other hand, what if the two works only have a word or two, or a single phrase, in common? Unless that phrase is the crux of the work, that probably isn't infringment. A court calls this "de minimus." What juries have to determine is how much is too much? This is a fuzzy line, somewhere above de minimus but below an exact copy. A jury must decide whether or not the alleged infringer has taken too much. |

| Ok, that was a lot to take in. Perhaps it would be helpful for me to quicky summarize the important points. For copyright infringment to exist: |

| The owner must have a valid copyright. The use must violate one of the six exclusive rights Independant creation of a work is never infringment Unprotectable elements are ignored when comparing two works The copyrighted elements do not have to be exactly the same, but similaries must be more than trivial |