| Chapter 6 |

| Burning CDs and My Mp3 Player |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. |

|

| Image provided by Fotocitizen. |

| In the beginning there was analog radio, and the analog radio was mediocre, but still the best available option. People used cassette tapes to record their favorite song off of the radio � if they were quick enough to hit record once the DJ started the song. (I had a number of tapes where the songs were missing the first few seconds because I was too slow). Nobody made a big fuss about this, partly because (1) the copies weren�t very good and (2) the notion of copyright infringement by a consumer was an odd idea back then. So many people were happy making low quality copies of their favorite songs off the radio. |

|

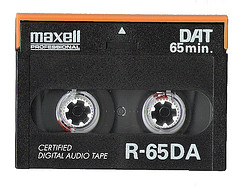

| Image provided by Arlette. |

| But technology marched on and the digital audio tape (DAT) came to market. At this, the recording industry threw up their hands and said �Wait! Now people can make perfect copies! This cannot be!� So they petitioned congress for some relief from the perceived threat to their business model. Please note, their business was not threatened but only their business model. They chose to fight and change the law rather than change their methods. Congress responded to their cries and created a compromise. First, technological limits and a fee were imposed on any device that recorded onto a DAT. I�ll skip the details of the device requirements, since that technology has fallen by the wayside. |

|

| Image provided by The Frankfurt School. |

| The important part is what came second � a small fee on any �digital audio recording medium.� This includes CD-Rs if they are marketed for music. If you go to the store you will see two kinds of CD-R � music and data. There is no physical differences between the discs � the only difference is that the price of the music CD-R includes this fee and the data CD-R does not. The money is eventually distributed back to the copyright owners through a complicated scheme. |

|

| Image obtained on Amazon.com. |

| In return, Congress wrote �No action may be brought under this title alleging infringement of copyright based on . . . the noncommercial use by a consumer of such a [] medium for making digital musical recordings or analog musical recordings.� |

| In plain English, if buy a music CD-R, you have paid for the privilege of making a copy of music onto that CD-R. Burning that copy is not copyright infringement as long as you use it in a "noncommercial" manner." In general terms, that means selling your burned copy or burning CDs as part of a business. |

| The story gets better because there is an interesting twist. When Congress wrote the statute, their first draft would have covered not only DAT devices, but computers as well. The computer industry objected, since paying a fee to the music industry would be silly for computers. Plus, the technical restrictions would have seriously impaired how computers function. So, computers were exempted from the act. At the time, this didn�t seem like a big deal. After all, they thought, who would put music on a computer? |

| The legal result is that copying your music onto a music CD-R is different than copying your music to your computer or to your mp3 player (mp3 players are viewed in the same category as computers - exempt from the Audio Home Recording Act). With a music CD-R, you paid for the copy, and with a computer or ipod, you haven�t paid for the additional copy. However, ripping legally obtained music onto your hard drive and on to your iPod is fair use. Even MusicUnited, a coalition of big name music and record publishers (who usually overstate their copyright claims) acknowledges that �burning a copy of CD onto a CD-R, or transferring a copy onto your computer hard drive or your portable music player, won�t usually raise concerns so long as the copy is made from an authorized original CD that you legitimately own and the copy is just for your personal use.� (format altered for clarity). |

| I cut off the last sentence of their webpage because it is wrong. They state that �[i]t�s not a personal use � in fact, it�s illegal � to give away the copy or lend it to others for copying.� It is true that you cannot lend the music CD-r for "direct or indirect commercial advantage." However, you can give the CD away to a friend. You can also lend to your friends. As long as it is a "noncommercial use" and you gain no "direct or indirect commercial advantage" you are free to dispose of the CD as you wish. The First Sale Doctrine, covered in chapter 1, allows you to distribute lawful copies that you own. Keep your use non-commercial, and you'll be ok. |

| This chapter is a little different than the rest. Rather than explain general copyright principles, we will discuss one specific section of the copyright statute known as the Audio Home Recording Act. Some of today's biggest copyright issues surround what you can and can't do with digital music files. This chapter will explain one aspect of the debate with a historical attempt at a solution which still factors into today's debate. |

|

| Image provided by Justin. |

|

| Who indeed? Image and example provided by Stephen Fulljames. Note the 22.8 days of music he has on his computer - and that's just one person who happened to take a picture of his itunes under a creative commons license. Imagine how much more is out there! |

| In this chapter I've used a lot of words in quotations - such as "noncommercial use." This is because I pulled the language straight from copyright law. Copyright law is trying to draw a line somewhere between selling a CD for profit (i.e. in a business) and using it for my own personal enrichment. But it is hard to determine where exactly that line is. As a general principle, you are more at risk when money (or a large volume of CDs) is changing hands. |