Introduction

Introduction

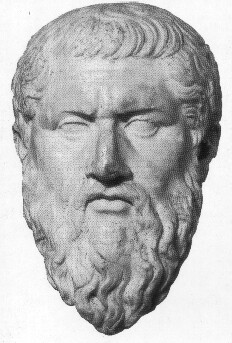

This is a list of all those dialogues that are generally or largely accepted

as having been written by Plato. It is taken

from ["Plato: Complete Works" Ed J.M. Cooper and

D.S. Hutchinson, pub Hackett (1997)] which also contains various

works, such as "Second Alcibiades" and "Rival Lovers" that are generally

thought to have been written by disciples of Plato rather than the master

himself. I warmly recommend this volume as it has an excellent introduction

which discusses the nature of a truly

Platonic outlook on philosophy and helpful summaries of each dialogue.

I here present the dialogues of Plato in a systematic order with a very brief account of what each is roughly about. The full text of Plato's works can be found here Plato's Works. The texts are somewhat scrambled, however. Better sources for individual dialogues can be found by following these links:

Euthydemus,

Protagoras, Gorgias and Meno

Charmides,

Critias, Laches, Lysis, Philebus, Sophist, Republic, Timaeus

Apology,

Alcibiades, Cratylus, Crito, Euthydemus, Euthyphro, Ion, Lesser Hippias

Menexenus,

Parmenides, Phaedo, Phaedrus, Symposium, Theaetetus

The web site of the International Plato Society can be found here. Bernard Suzanne's site devoted to the dialogues can be found here, and his links to on-line copies of the dialogues, here.

Over time, I intend to expand this page to include a serviceable summary of each dialogue complete with key quotes and references. At present [June 2007] this is about three-quarters complete!

I have just published a book: "New Skins for Old Wine: Plato's Wisdom for Today's World."

Euthyphro

Euthyphro

Socrates is on his way to being tried for his life, but gets into a conversation

regarding whether piety - a front for "that which is good and approvable"

- is arbitrary and extrinsic (chosen by "thhe gods") or

else inevitable and intrinsic (recognized for what it is by "the gods").

This is one of my favourite dialogues.

- "Consider this: Is the pious being loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is being loved by the gods" [10a]

- "What benefit do the gods derive from the gifts they receive from us? What they give us is obvious to all.... but how are they benefited by what they receive from us? Or do we have such an advantage in trade that we receive all our blessings from them and they receive nothing from us?" [15a]

Apology

The account of Socrates' trial for "corrupting the youth of Athens." The fact that it was the "Democratic" Athenian party that conspired to accuse, try, convict and execute Socrates forever disinclined Plato to have much time for "democratic values" and inclined him to a more aristocratic and autocratic view of politics, as becomes clear in his two political works: Republic and Laws.

Crito

Crito

Socrates explains why he chooses to accept the unjust verdict of the Athenian

Democrats. A discussion of what justice is follows.

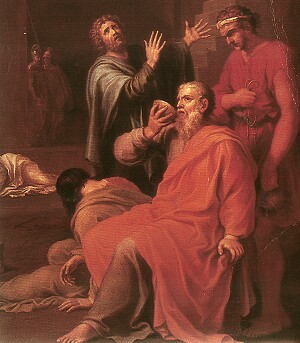

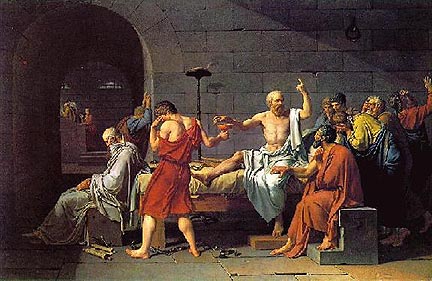

Phaedo

The account of the last hours of Socrates, in which he discusses with his dearest friends the immortality of the soul. Plato uses this as a pretext to introduce his doctrine of "The Eternal Forms". This is intensely moving and Socrates' dignity is truly inspiring. It is one of my favourite dialogues.

- The account is given by Phaedo.

- He tells that on the morning of Socrates execution, he found him sitting with various friends, his wife Xanthippe and his baby. [57a-59e]

- Plato was not present, being poorly. [59b]

- Xanthippe was very upset and Socrates asked that she be taken home. [60a]

- Socrates explains that he has recently taken to writing poetry to discharge a divine obligation put on him in a dream to "practice and cultivate the arts." [60b-61c]

- He discusses why suicide is wrong, basically because human beings are the possessions of the gods and do not own their own lives to dispose of as they will. [61d-63b]

- Socrates then speaks of his hope for life after death. [63c-64c]

- "I have good hope that some future awaits men after death, as we have been told for years, a much better future for the good than for the wicked." [63c]

- "The one aim of those who practice philosophy in the proper manner is to practice for dying and for death." [64a]

- He asserts the superiority of the soul to the body and the difficulty that the soul experiences in its entanglement with the physical. [64d-66d]

- "The philosopher - more than other men - frees the soul from association with the body, as much as possible." [65a]

- "What again shall we say of the actual acquisition of knowledge? Is the body, if invited to share in the inquiry, a hinderer or a helper? I mean to say, have sight and hearing any truth in them? Are they not, as the poets are always telling us, inaccurate witnesses? And yet, if even they are inaccurate and indistinct, what is to be said of the other senses, for you will allow that they are the best of them?.... For in attempting to consider anything in company with the body she is obviously deceived." [65b]

- "All wars are due to the desire to acquire wealth, and it is the body and the care of it, to which we are enslaved, which compels us to acquire wealth; and all this makes us too busy to practice philosophy." [66d]

- He says that death is no evil, but a boon; being the separation of the soul from the trappings of the body. [66e-67d]

- "If it is impossible to attain any pure knowledge with the body, then one of two things is true: either we can never attain knowledge, or we can do so after death." [66e]

- "It would be ridiculous for a man who to train himself in life to live in a state as close to death as possible, and then to resent it when it comes." [67d]

- He says that the basis of true virtue is wisdom. [67e-]

- "With wisdom we have real courage and moderation and justice and, in a word, true virtue; with wisdom, whether pleasures and fears and all such things be present or absent.... without wisdom such virtue is only an illusory appearance of virtue; it is in fact fit for slaves, without soundness or truth, whereas, in truth, moderation and courage and justice are a purging away of all such things; and wisdom itself is a kind of cleansing or purification." [69b]

- "There are.... many who carry the thyrsus, but the Bacchants are few." [69d]

- Cebes then says:

- "Men find it very hard to believe what you said about the soul. They think that after it has left the body, it no longer exists anywhere; but that it is destroyed and dissolved..... and.... is dispersed like breath or smoke.... If indeed it gathered itself together and existed by itself and escaped these evils.... there would then be much good hope, Socrates, that what you say is true; but to believe this requires a good deal of faith and persuasive argument - to believe that the soul still exists after a man has died and that it still possesses some capability and intelligence." [70a-b]

- Socrates embarks on a proof of the immortality of the soul.

- He first discusses opposites, and how one comes from the other. [70e-71d]

- He then argues that life must come from death and so reincarnation must be true and so there must be life after death. [71d-72a]

- He then intimates an elementary understanding of the second law of thermodynamics - but rejects it as somehow absurd. [72b-d]

- Cebes then intervenes, saying that if learning is recollection the soul must exist before birth; which corroborates the theory of reincarnation. [72e-73a] He refers to the demonstration in Meno.

- Socrates rehearses a proof for the benefit of Simmias, extending and honing the theory to claim that what is recalled are the forms themselves. [73b-76d] He then says that this proves the soul's immortality and independent intelligence. [76d-77a]

- Simmias and Cebes are still unconvinced of the soul's survival after death. [77b-78b] Hence, Socrates then turns to a consideration of the soul's character. [78b-]

- "We should then examine to which class of being the soul belongs, and as a result either fear for the soul or be of good cheer." [78b]

- He argues that the soul is not composite and therefore cannot de-compose. [78c-81a]

- "Assume two kinds of existence: the visible and the invisible.... the invisible always remains the same, whereas the visible never does." [79a]

- "When the soul makes use of the body to investigate something, be it through hearing or seeing or some other sense - for to investigate something through the body is to do it through the senses - it is dragged by the body to the things that are never the same, and the soul strays and is confused and is dizzy.... but when the soul investigates by itself it passes into the realm of what is pure, ever existing, immortal and unchanging; and being akin to this it always stays with it whenever it is by itself and can do so; it ceases to stray and remains in the same state as it is in touch with things of the same kind, and its experience then is what is called wisdom." [79c-d]

- "Is it not natural for the body to dissolve easily and for the soul to be altogether indissoluble, or nearly so?" [80b]

- He cautions about attatchement to the physical world, as the cause of ignorance, suffering and re-incarnation. [81b-84b]

- "The soul is imprisoned in and clinging to the body.... it wallows in every kind of ignorance.... the worst feature of this imprisonment is that it is due to desires, so that the prisoner himself is contributing to his own incarceration most of all.... philosophy gets hold of their soul in that state, then gently encourages it and tries to free it.... persuading it to withdraw from the senses - in as far as it is not compelled to use them - and bids the soul.... to trust only itself and whatever reality - existing by itself - the soul, by itself,, understands; and not to consider as true whatever it examines by other means." [82e-83b]

- "Every pleasure and every pain provides, as it were, another nail to rivet the soul to the body.... It makes the soul corporeal, so that it believes that truth is what the body says it is." [83d]

- Simmias intimates that he is still not satisfied.

- He suggests that the soul is related to the body as the attunement of a lyre is to the physical instrument. When the lyre is destroyed, so is its harmony. [84c-86e] He says:

- "One should achieve one of these things: learn the truth about them; or find it for oneself; or, if that is impossible, adopt the best and most irrefutable of men's theories. [85c-d]

- Cebes joins in, pointing out at length that it is not good enough to argue that the soul is considerably more robust than the body; but that it must somehow be established that it is absolutely immortal. [87a-88c]

- "When one who lacks skill in arguments puts his trust in an argument as being true, then shortly afterwards believes it to be false - as sometimes it is and sometimes it is not - and so with another argument and then another. You know how those in particular who spend their time studying contradiction in the end believe themselves to have become very wise and that they alone have understood that there is no soundness or reliability in any object or any argument; but that all that exists simply fluctuates up and down as if it were in the [violent straits of] Euripus and does not remain in the same place for any time at all!" [90b-c]

- "We should not allow into our minds the conviction that argumentation has nothing sound about it; much rather we should believe that it is we who are not yet sound and that we must take courage and be eager to attain soundness." [90e-91a]

- "The uneducated, when they engage in argument about anything, give no thought to the truth about the subject of discussion, but are only eager that those present will accept the position they have set forth." [91a]

- "I am thinking.... that if what I say is true, it is a fine thing to be convinced; if, on the other hand, nothing exists after death, at least for this time before I die I shall distress those present less with lamentations, and my folly will not continue to exist.... but will come to an end in a short time." [91a-b]

- "Give but little thought to Socrates, but much more to the truth. If you think that what I say is true, agree with me; if not, oppose it with every argument and take care that in my eagerness I do not deceive myself and you." [91c]

- Socrates points out that the soul cannot be a harmony of the body if it exists prior to the body, as Cebes indeed believes. [91d-92e] He adds that if the soul was derivative of the body, it is difficult to see how it could govern the body. [93a-95a]

- "A harmony does not direct its components, but is directed by them." [93a]

- "Can it be true about the soul that one soul is more and more fully a soul than another; or is less and less fully a soul - even to the smallest extent?" [93b]

- "If the soul was a harmony, it would never be out of tune with the stress and relaxation [of the body].... but that it would follow and never direct them..... it appears to do quite the opposite; ruling over all the elements of which - one says - it is composed.... as Homer wrote.... 'Endure, my heart, you have suffered worse than this.'" [94d]

- Socrates finally turns to the fundamental problem: that of the absolute immortality of the soul. [95b-]

- "Does the brain provide our senses of hearing and sight and smell, from which come memory and opinion, and from memory and opinion which has become stable, comes knowledge?" [96b]

- "I am far, by Zeus, from believing that I know the cause of any of those things. I will not even allow myself to say that where one is added to one, either the one to which it is added or the one that is added become two.... I wonder that, when each of them is separate from the other, each of them is one - nor are they then two; but that, when they come near to one another, this is the cause of their becoming two - the coming together and being placed closer to one another." [96e-97b]

- "It is Mind that directs, and is the cause of everything." [97c]

- "If then one wished to know the cause of each thing - why it comes to be, or perishes or existss - one had to find out what was the best way for it to be, or to be acted upon, or to act." [97c-d]

- "Imagine not being able to distinguish the real cause from 'that without which the cause would not be able to act as a cause'." [99b]

- He introduces the theory of forms. [100b-]

- "Not only does the opposite not admit its opposite; but that which brings along some opposite into that which it occupies. That which brings this along will not admit the opposite to that which it brings along." [105a]

- "Whatever the soul occupies, it always brings to life.... so the soul will never admit the opposite of that which it brings along.... so the soul is deathless." [105d-e]

- He concludes that the soul is necessarily immortal. [106a-107c]

- He then tells a myth about what happens to the soul after death. [107d-108]

- He interposes an account of the spherical nature of the Earth, [109a-b] and the finite height of the atmosphere [109c-e]

- "No sensible man would insist that these things are as I have described them, but I think that it is fitting for a man to risk the belief - for the risk is a noble one - that this, or something like this, is true about our souls.... That is the reason why a man should be of good cheer about his own soul, if during his life he has.... seriously concerned himself with the pleasures of learning, and adorned his soul not with alien but with its own ornaments, namely: moderation, righteousness, courage, freedom and truth." [114d-e]

- Socrates then takes his leave of his friends, [115a-115e] has a bath, [116a] drinks the hemlock, [116b-117e] and dies. [118a]

Theaetetus

Plato's ground breaking discussion of the question "What is knowledge?" This is the foundation document of the science of Epistemology. It is arguably Plato's greatest work. Two ex students of Socrates (who is now dead) meet. They lament the impending death of Theaetetus, a protégé of Socrates. One of them - Terpsion - then has a slave read out a book that he had written some time ago as a record of a conversation between Socrates, Theodorus and Theaetetus.- Theodorus describes Theaetetus, son of Euphronius of Sunium, as follows:

- "If he were beautiful, I should be extremely nervous of speaking with him with enthusiasm, for fear I might be suspected of being in love with him. But as a matter of fact.... he is not beautiful at all, but is rather like you [Socrates], snub-nosed, with eyes that stick out; though these features are not quite as pronounced in him.... I assure you that among all the people I have ever met.... I have never yet seen anyone so amazingly gifted." [143e-144a]

- Socrates suggests to Theaetetus that before accepting such praise one should determine whether the originator has any expertise to justify their expressed opinion. The implication is that Socrates will test Theaetetus by means of the dialectic and see for himself whether Theodorus' judgement is accurate. [144b-d]

- Socrates suggests that the question "what is knowledge" should be investigated. [144e-146c]

- Theaetetus proposes some examples of knowledge, but Socrates rejects this tactic as avoiding the issue. [146d-148e]

- Socrates then introduces the idea that he will help Theaetetus to "give birth" to an idea of what knowledge is, as a midwife. [149a-151d]

- "Now my art of midwifery is just like theirs.... the difference is that I attend men, not women, and that I watch over the labour of their souls, not of their bodies. And the most important thing about my art is the ability to apply all possible tests to the offspring, to determine whether the young mind is being delivered of a phantom, that is, an error, or a fertile truth... The common reproach against me is that I am always asking questions of other people but never express my own views about anything, because there is no wisdom in me; and that is true enough.... I am not in any sense a wise man; I cannot claim as the child of my own soul any discovery worth the name of wisdom. But with those who associate with me it is different. At first some of them may give the impression of being ignorant and stupid; but as time goes on.... all whom God permits are seen to make progress.... they discover within themselves a multitude of beautiful things, which they bring forth into the light. But it is I, with God's help, who deliver them of this offspring....

- Theaetetus then proposes that "knowledge is perception". [151e]

- Socrates responds to this by linking it with Protagoras' relativistic claim that "Man is the measure of all things," and Heraclitus idea that "Being is motion." [152a-153d]

- "You know that he [Protagoras] puts it sometimes like this, that as each thing appears to me, so it is for me; and as it appears to you, so it is for you - you and I each being a man?" [152a]

- "This is certainly no ordinary theory.... If you call a thing large, it will reveal itself as small, and if you call it heavy, it is liable to appear as light, and so on with everything - because nothing is one or anything or any kind of thing..... the things of which we naturally say that they 'are', are in process of coming to be.... we are wrong when we say that they 'are', since nothing is, but everything is coming to be.... As regards this point of view, all the wise men of the past - except Parmenides - stand together." [152d-e]

- "There is good enough evidence for this theory that what passes for being and becoming are a product of motion, and that not-being and passing-away result from a state of rest." [153a]

- Socrates then points out -at some length - that perceptions are necessarily subjective. [153e-157c]

- Timaeus expresses confusion and even doubt that Socrates is being serious. [157c] Socrates claims that he is just helping Timaeus to think things out for himself. [157c-d] He then points out that one can be mistaken in one's perceptions - how then can perception be knowledge, forr knowledge cannot be falsehood. [157e-158b] Socrates then points out that we cannot clearly establish that we are not now dreaming, so all our perceptions may be fantastical. [158a-e] He then returns to his theme that all perceptions are subjective and relative to the percipient. [158e-160d]

- "I'll tell you the kind of thing that might be said by those people who propose it as a rule that whatever a man thinks at any time is the truth for him. I can imagine them putting their position by asking you this question: 'Now, Theaetetus, suppose you have something which is an entirely different thing from something else. Can it have in any respect the same powers as the other thing? And observe, we are not to understand the question to refer to something which is the same in some respects while it is different in others, but to that which is wholly different.'" [158e]

- "Then my perception is true for me - because it is always a perception of that being that is peculiarly mine; and I am judge, as Protagoras said, of things that are: that they are, for me; and of things that are not: that they are not." [160c]

- Socrates then congratulates Theaetetus on having - apparently - given birth to his first child. [160d-161b]

- He then proceeds to ruthlessly demolish what he had seemed to approve of. [161c-164b]

- "If whatever the individual judges by means of perception is true for him; if no man can assess another's experience better than he, or can claim authority to examine another man's judgement and see if it be right or wrong; if, as we have repeatedly said, only the individual himself can judge of his own world, and what he judges is always true and correct: how could it ever be, my friend, that Protagoras was a wise man...? To examine and try to refute each other's appearances and judgements, when each person's are correct - this is surely an extremely tiresome piece of nonsense, if the Truth of Protagoras is true, and not merely an oracle speaking in jest...." [161d-162a]

- He points out that it is one thing to see a written language or hear a spoken one; but another to understand either. [163a-c]

- He then insists that knowledge can be associated with memory rather than any kind of immediate sense perception. [163d-164b]

- "Then we have got to say that perception is one thing and knowledge another." [164b]

- Socrates tries to get Theodorus to defend Protagoras, but he declines to do so. [164c-165a] Socrates then argues that whereas one can both see and not see something (that is with one eye and the other) one cannot both know and not know something. [165b-d]

- Socrates then tries hard to argue Protagoras' case for him. He tries to nuance it in a way that might make it morally acceptable. [166a-168c]

- "Each one of us is the measure both of what is and of what is not; but there are countless differences between men for just this reason, that different things both are and appear to be to different subjects.... the man whom I call wise is the man who can change the appearances - the man who in any case where bad things both appear and are for one of us, works a change and makes good things appear and be for him." [166d]

- "When a man's soul is in a pernicious state, he judges things akin to it, but giving him a sound state of the soul causes him to think different things, things that are good. In the latter event, the things which appear to him are what some people, who are still at a primitive stage, call 'true'; my position, however, is that the one kind are better than the others, but in no way 'truer'." [167b]

- He then once more tries to get Theodorus to defend Protagoras. This time he succeeds, up to a point. [167c-169d]

- Socrates expresses doubt that Protagoras would have agreed with the nuance that Socrates has just placed on his teaching [169e] and then argues that Protagoras' basic case is palpably absurd, for Protagoras has to admit that his proposition is truly false for those who disagree with him, but those that do not agree with him do not have to make a similar concession. [170a-171d]

- Socrates then points to the fields of medicine and politics where it is clear that some people are wiser than others. [171e-172b] He then discusses lawyers, and suggests that the practice of law turns good men in to villains. [172c-173b] He then contrasts the case of philosophers and uses this as a pretext to consider the question of virtue. [173c-177c]

- "What is Man? What actions and passions properly belong to human nature and distinguish it from all other beings? This is what he wants to know and concerns himself to investigate." [174b]

- "The philosopher is the object of general derision, partly for what men take to be his superior manner, and partly for his constant ignorance and lack of resource in dealing with the obvious." [175b]

- "It is not possible.... that evil should be destroyed - for there must always be something opposed to the good; nor is it possible that it should have its seat in heaven; but it must inevitably haunt human life, and prowl about this earth. This is why a man should make all haste to escape from earth to heaven; and escape means becoming as like God as possible; and a man becomes like God when he becomes just and pure, with understanding." [176b]

- "In God there is no sort of wrong whatsoever; He is supremely just, and the thing most like Him is the man who has become as just as it lies in human nature to be." [176c]

- "Everything else that passes for ability.... [is either] a poor cheap show [or].... a matter of mechanical routine. If, therefore, one meets a man who practices injustice.... the best thing for him by far is that one should never grant that there is any sort of ability about his unscrupulousness.... we must therefore tell them the truth - that their very ignorance of their true state fixes them the more firmly therein. For they do not know what is the penalty of injustice, which is the last thing of which a man should be ignorant." [176c-d]

- "There are two patterns set up in reality. One is divine and supremely happy; the other has nothing of God in it, and is the pattern of deepest unhappiness.... the evildoer does not see.... that the effect of his unjust practices is to make him grow more and more like the one and less and less like the other." [176e-177a]

- Socrates then discusses whether a democratic community consensus as to what is "just" is a legitimate basis for "justice." [177c-179b] He treats this in terms of "future utility" and quickly establishes that the mere fact that a majority decide that something will be useful in the future does not make it so. [178c-179a] He then argues that some individuals have a real expertise and should be deferred to, while others have no such expertise and should be ignored. [179b]

- He then says that perhaps he is being too harsh, that the whole matter must be given another chance and proposes going back to its first principle - Heraclitus' contention that "being is mottion." [179c-d] Theodorus expresses the view that this is impossible, as the Heraclitian party is disparate and largely manic. [179e-180a]

- Socrates defers to Theodorus and then admits that there is - in any case - an opposing view (that of Parmenides) thaat all being is Unitary and Static. [180e] He suggests that this view should be investigated too. However, he first spends more words on criticizing the view that all things continually change. [181a-183c] In the event he cries off from analysing Parmenides' position, on the pretext that it would be insulting to do so as an interlude here. [183d-184a]

- Socrates then engages again with Theaetetus, and elicits from him the acknowledgement that the senses are only instrumental in the experience of reality, but that it is the soul itself that truly perceives [184b-185e] and forms value judgements. [186a-c] Theaetetus readily concedes that "perception" is not "knowledge", but that knowledge arises when the soul starts to reason about experience. [186d-187a]

- Theaetetus then suggests that "knowledge is true judgement." [187b]

- "If we continue like this, one of two things will happen. Either we shall find what we are going out after; or we shall be less inclined to think that we know things which we don't know at all - and even that would be a reward we could not fairly be dissatisfied with." [187c]

- "It is better to achieve a little - well, than a great deal - unsatisfactorily." [187e]

- Socrates shows that the idea of "false judgement" is self contradictory, because it is absurd for some one to be wrong about something that he knows and possible to have a judgement about something of which he is ignorant or does not exist. [187c-189b]

- He then suggests that "false judgement" might consist in mistaking one thing for another. [189c-190a]

- "It seems to me that the soul - when it thinks - is simply carrying on a discussion.... and when it arrives at something definite, either by a gradual process or a sudden leap, when it affirms one thing consistently.... we call this its judgement." [190a]

- He rejects this on the basis that both things would have to be known, and so could not be mistaken. [190b-d]

- Theaetetus then points out that it is possible to mistake two things that are similar to each other when they are seen at a distance. Socrates agrees and suggests that false judgement lies in mis-identifying something that is being perceived with something else that is being remembered. [190e-195b] He calls this state of affairs "heterodoxy". [190e, 193d] In effect he has proposed the "Correspondence Theory of Truth".

- Socrates then doubts the conclusion they have reached, because it seems to him that there can be error about ideas themselves [195c-196d] - contrary to what he had earlier asserted.. [190b-d, 192a]

- He points out that they have been trying to determine what knowledge is - which means that this is presently unknowwn to them - and yet have regularly presumed to "know" various other things. [196d-e] He suggests that this is a fundamental difficulty that cannot be avoided in any straight-forward manner. He therefore proposes to consider what knowledge is like, rather than what it is. He compares knowledge with the possession of birds, held captive in an aviary. The birds are ideas and the aviary the memory. [197a-199a] He points out that there are two modes of acquiring a bird; first capturing it from the wild and putting it in the aviary, second catching a bird that is already in the aviary. The second bird is "possessed" even before it has been caught in the hand, by virtue of it being already within the aviary and hence the ownership of the bird keeper. [198d-199a] Hence it is possible to "know" and "not know" something at the same time, as there are degrees of immediacy of knowledge. [199c]

- Socrates once more pours doubt on this conclusion. He says that it is absurd that ignorance can arise from knowledge, and when Theaetetus tries to nuance the aviary model by adding birds that represent falsehoods, Socrates claims to show that this is no less absurd. [199d-200c] Socrates then suggests that they were perhaps wrong - after all - to discuss heterodoxy before knowledge. [200d]

- Socrates then insists that "true judgement" or orthodoxy is not at all the same a knowledge, episteme. [201a-c]

- Theaetetus agrees and then suggests that "knowledge - episteme - is true judgement - orthodoxy - with an account - logos." [201d]

- Socrates welcomes this idea and expands on it. [201e-202d]

- However, he then points out that an account can only go so far, and that the underlying concepts upon which it is based cannot be accounted for. How then, can one be said to know something when the supposed basis of this knowledge is unknown? [202e-206b]

- "Let the complex be a single form resulting from the combination of the several elements when they fit together; and let this hold both of language and of things in general." [204a]

- "If the complex is both many elements and a whole, with them as its parts, then both complexes and elements are equally capable of being known and expressed." [205d]

- "If anyone maintains that the complex is by nature knowable and the element is unknowable, we shall regard this as tomfoolery, whether it is intended to be or not." [206b]

- Socrates proceeds to discuss what might be meant by "an account". [206c-210b]

- The first possibility is "to put one's thought into words." [206d] Socrates says that anyone can do this, whether they understand something or not, so this is not the required meaning. [206d-e]

- The second possibility is "to answer questions about something by referring to its detailed makeup." [207a-208a] Socrates points out that this can be a matter of accident, so this is not the required meaning. [208b]

- The third possibility is "to distinguish something from all other things." [208c-e] Socrates points out however that differences between things are just as much the subject of judgement as are similarities, so "distinguishing something from all other things" is just a part of "orthodoxy" and nothing to do with "logos". [209a-d]

- He then points out that they are on the verge of saying that episteme is orthodoxy plus..... episteme, which is no help whatsoever. [209e-210b]

- Socrates and Theaetetus then admit defeat. [210c-d]

- "If in the future you should ever attempt to conceive or should succeed in conceiving other theories, they will be better ones as the result of this inquiry. And if you remain barren, your companions will find you gentler and less tiresome; you will be modest and not think that you know whet you don't know. This is all that my art can achieve - nothing more. I do not know any of the thhings that other men know - the great and inspired men of today and yesterday. But this art of midwifery my mother and I had allotted to us by God; she to deliver women, I to deliver men that are young and generous of spirit, all that have any beauty. And now I must go to the King's Porch to meet the indictment that Meletus has brought against me; but let us meet here again in the morning, Theodorus." [210c-d]

There is another point also in which those who associate with me are like women in child-birth. They suffer the pains of labour, and are filled day and night with distress; indeed they suffer far more than women. And this pain my art is able to bring on, and also to allay.....

And when I examine what you say, I may perhaps think that it is a phantom and not truth, and proceed to take it quietly from you and abandon it. Now if this happens, you mustn't get savage with me.... people have often before now got into such a state with me as to be literally ready to bite when I take away some nonsense or other from them. They never believe that I am doing this in goodwill; they are so far from realizing that no god can wish evil to man, and that even I don't do this kind of thing out of malice, but because it is not permitted to me to accept a lie and put away truth." [150c-151c]

Protagoras

This is Plato's dramatic masterpiece. It is the foundation document for Plato's theory of ethics. It deals with the nature of virtue and discusses whether it is something that can be taught. Socrates argues that knowledge is the basis of all virtue, as he does in Meno. He also argues that the rational pursuit of abiding pleasure underpins all ethical action. This is one of my favourite dialogues.- Socrates encounters an anonymous friend, who accuses him - correctly - of coming from courting Alcibiades. [309a-b] Socrates adds that he was distracted from his beloved by having also met Protagoras, who he describes as having "superlative wisdom"[309b] and being "the wisest man alive." [309d] He then procedes to give an account of the encounter.

- It all started with Hippocrates rousing Socrates before daybreak, with the demand that he go and meet with Protagoras so that Hippocrates could learn by listening to their debate. [310a-311a]

- Socrates challenges Hippocrates motivation.

- "You are about to hand over your soul for treatment to a man who is, as you say, a sophist. As to what exactly a sophist is.... you are ignorant of this, you don't know whether you are entrusting your soul to something good or bad." [312c]

- "Those who take their teachings from town to town and sell them wholesale or retail to anybody who wants them, recommend ass their wares; but I wouldn't be surprised, my friend, if soem of these people did not know which of their wares are beneficial and which detrimental to the soul. Likewise those who buy from them." [313d]

- "You and I are still a little too young to get to the bottom of such a great matter." [314b]

- They then go off in search of Protagoras. They find him in the company of many other sophists and their pupils [314c-315e] and also Alcibiades "the Beautiful". [316a]

- Protagoras agrees to talk with Socrates in public, regarding the aspirations of Hippocrates to become his pupil. [316b-318a] He then claims to be able to make Hippocrates a better man, day by day. [318b]

- Socrates asks

- "exactly how will he go away a better man, and in what will he make progress each and every day he spends with you?" [318d]

- Protagoras claims to teach

- "sound deliberation.... how to realize one's maximum potential for success in political debate and action." [319a]

- Socrates says that this amounts to be "the art of citizanship" [319a] and questions whether this is teachable. He bases his doubt on the Athenian practice of democracy, which implied that politics and citizanship is not a skill; [319b-e] and also on the practical inability of virtuous men to educate their sons in virtue. [320a-b]

- "I could mention a great many more, men who are good in themselves but have never succeeded in making anyone else better; whether family members or total strangers." [320b]

- Protagoras then gives a long speech.

- He tells a myth about how the human race came by a share in practical wisdom (courtesy of Promethius' theft of Athena) and a knowledge of fire (courtesy of Promethius' theft of Hephaestus), but not political wisdom (for this was possessed by Zeus, and Promethius was unable to purloin this. [320c-321e] He says that it is because humanity has a share in divine wisdom that mankind worships the gods, because they had a kind of kinship with them; and also that they started to develop civilization. [322a-b] However, not understanding the art of politics, they wronged each other and seemed liable to become extinct. [322c] Zeus had pity on mankind and

- "sent Hermes to bring justice and a sense of shame to humans",

- with each person having an equal share

- "For cities would never come to be if only a few possessed these, as is the case with the other arts." [322d]

- "It is madness not to pretend to justice, since one must have some trace of it or not be human." [323c]

- "In the case of evils that men universally regard as afflictions due to nature or bad luck, no one ever gets angry with anyone so afflicted or reproves, admonishes, punishes or tries to correct them. We simply pity them." [323d]

- "In the case of the good things that accrue to men through practice and training and teaching, if someone does not possess these goods but rather their corresponding evils, he finds himself the object of anger, punishment and reproof.... and the reason is clearly that this virtue is regarded something acquired through practice and teaching." [323e-324a]

- "No one punishes a wrong-doer in consideration of the simple fact that he has done something wrong, unless one is exercising the mindless vindictiveness of a beast. Reasonable punishment is not vengeance for past wrong - for one cannot undo what has been done - but is undertaken with a view to the future; to deter both the wrong-doer and whosever sees him being punished from repeating the crime..... Therefore.... the Athenians are among those who think that virtue is acquired and taught." [324b-d]

- "Does there.... exist one thing which all citizans must have for there to be a city?..... For is such a thing exists, and this is.... justice, and temperance and piety - what I may collectively call the virtue of a man.... and good men give their sons an education in everything but this, then we have to be amazed at how strangely our good men behave.... Do you think they so not have them taught this?.... We must think they do, Socrates." [325c]

- He then describes at length the efforts made by educators to inculcate discipline and virtue in their students. [325d-326e]

- "It is to our collective advantage that we each possess justice and virtue, and so we all gladly tell and teach each other what is just and lawful." [327b]

- He argues that the reason that the sons of good men are not necessarily virtuous is that they happen not to have inherrited the personal disposition to virtue possessed by their father. [327c-328a]

- He concludes by restating his claim to have the ability to teach virtue. [329a-d]

- Socrates expresses his immense gratitude to Protagoras.

- He intimates that he has one small difficulty. [328d-d]

- "Is virtue a single thing, with justice and temperance and piety its parts, or are the things I have just listed all names for a single entity?" [329d]

- Protagoras replies:

- "Virtue is a single entity, and the things you are asking about are its parts." [329d]

- Socrates then asks

- "Does each also have its own unique power or function?... Are they unlike each other, both in themselves and in their powers or functions?.... Then none of the other parts of virtue is like knowledge, or like justice, or like courage, or like temperance or like piety?" [330b]

- "Isn't piety the sort of thing that is just, and isn't justice the sort of thing that is pious?.... Justice is the same sort of thing as piety, and piety as justice." [331b]

- Protagoras reluctantly agrees.

- "Justice does have some resemblance to piety. Anything at all resembles any other thing in some way.... but it's not right to call things similar becuse they resemble each other in some way, however slight, or to call them dissimilar because there is some slight point of disagreement." [331d-e]

- Socrates then proposes a detailed syllogism which attempst to establish that wisdom is identical with temporance. [332a-333b]

- He than engages Protagoras in a debate about "what is good." Protagoras objects that it is necessary to define the context before saying that something is "good". [333c-334c]

- "The good is such a mutifaceted and variable thing." [334b]

- Protagoras and Socrates fall out over their debating styles.

- Socrates made to leave; [334d-335c] but was prevented by Callias, [335d-336b] Alcibiades, [336b-d] Critas, [336d-e] Prodicus [337a-c]

- "A good opinion is guilelessly inherent in the souls of the listeners, but praise is all too often merely a deceitful verbal expression." [337b]

- and Hippias [337c-338b]

- "Like is akin to like by nature, but convention - which tyranizes the human race - often constrains us contrary to nature." [337d]

- Protagoras reluctantly agrees to continue the debate on Socrates' terms. [338b-e]

- He quotes the poet Simonides as saying that it is difficult to become good and then as saying that to say exactly this is false. [339a-340a]

- Socrates rescues the poet from inconsistency by destinguishing "become good" from "be good". He says that is hard to become good, but impossible to remain good once one has attained this state. [340b-d]

- Protagoras disagrees. [340e-341e]

- Socrates claims that the success of Sparta is based on the practice of philosophy in that State, which is itself a state secret, [342a-343b] goes on to claim that Simonides' poem must be analyzed very carefully and procedes to do so. [343c-347a]

- "The good is susceptible to becoming bad.... but the bad is not susceptible to becoming; it must always be." [344d]

- "It is impossible to be a good man and continue to be good, but possible for one and the same person to become good and also bad; and those are best for the longest time whom the god's love." [345c]

- "I am pretty sure that none of the wise men think that any human being willingly makes a mistake or willingly does anything wrong or bad." [346e]

- Socrates insists that the discussion of poetry should give way to a direct philosophical debate, [347b-348b] and reluctantly Protagoras agrees. [348c]

- Socrates flatters Protagoras. [348d-e]

- "Not only do you consider yourself to be noble and good, but unlike others.... you are not only good yourself, but able to make others good as well.... and you advertise yourself as a teacher of virtue, the first ever to have deemed it appropriate to charge a fee for this." [348e]

- He then invites Protagoras to review what he had said earlier about the virtues. [349a-d]

- "All these are parts of virtue, and while four of them are reasonibly close to each other, courage is completely different from all the rest." [349d]

- He then traps Protagoras into saying that:

- "Those with the right sort of knowledge are always more confident than those without it." [350a]

- But Protagoras points out that:

- "If I was asked if the confident are courageous.... I would have said, not all af them." [350c]

- Socrates then asks

- "Just insofar as things are pleasurable, are they not good? I am asking whether pleasure itself is not a good?" [351e]

- He explains his purpose in asking:

- "Most people think this way about [knowledge], that it is not a powerful thing, neither a leader nor a ruler. They do not think of it in that way at all; but rather in this way: while knowledge is often present in a man, what rules him is not knowledge but rather anything else - sometimes desire, sometimes pleasure, sommetimes pain, at other times love, often fear; they think of his knowledge as being utterly dragged around by all these other things as if it were a slave. Now, does the matter seem like that to you; or does it seem to you that knowledge is a fine thing capable of ruling a person, and if someone were to know what is good and bad, then he would not be forced by anything to act otherwise than knowledge dictates, and intelligence would be sufficient to save a person?" [352b-c]

- Protagoras chooses the second option, [352d] and Socrates agrees. [352e]

- Socrates then attempts to give a rational account of"being overcome by pleasure". [353c]

- "Do you hold.... that this happens to you in circumstances like these - you are often overcome by pleasant things like food or drink or sex, and your do these things all the while knowing that they are ruinous?.... In what sense do you call these ruinous? Is it that each of them is pleasant in itself and produces immediate pleasure, or is it that later they bring about disease and poverty and many other things of that sort? Or even if it doesn't bring about these things later, but gave only enjoyment, would it still be a bad thing; just because it gave enjoyment in any way?" [353c-d]

- "Does it not seem to you, my good people, as Protagoras and I maintain, that these things are bad on account of nothing other than the fact that they result in pain and deprive us of other pleasures?" [353e]

- "Would you call these [other] things good for the reason that they bring about intense pain and suffering, or because they ultimately bring about health and good condition of bodies and preservation of cities and power over others and wealth?" [354b]

- "These things are good only because they result in pleasure and in the relief and avoidance of pain? Or do you have some other criterion in view, other than pleasure and pain, on the basis of which you would call these things good?" [354b]

- "So then you pursue pleasure as being good and avoid pain as being bad?" [354c]

- "Is it enough for you to live life pleasantly, without pain? If it is enough..... then your position will become absurd, when you say that frequently a man, knowing the bad to be bad, nevertheless does that very thing, when he is able not to, having been driven and overwhelmed by pleasure; and again when you say that a man knowing the good is not willing to do it, on account of immediate pleasure, having been overcome by it." [355a-b]

- He argues that temporally remote pleasure and pain is commensurate with immediate pleasure and pain. [356b-c] The difficulty is only that future pleasure and pain is not so clearly perceived as those in the present; [356c] they are inaccurately measured [357b] - we have inadequate knowledge of them, [357c] and so we fail because of ignorance. [357d]

- "Those who make mistakes with regard to good and bad do so because of.... a lack of that knowledge that you agreed was measurement. And the mistaken act done without knowledge you must know is one done from ignorance." [357d-e]

- All the sophists present agree with Socrates' conclusion. [358a]

- "If the pleasant is the good, no-one who knows or believes there is something else better than what he is doing - something possible - will go on doing what he has been doing when he could be doing what is better. To 'give in to oneself' is nothing other than ignorance, and to 'control onself' is nothing other than wisdom." [358c]

- Once again, all the sophists present agree with Socrates' conclusion. [358d]

- Socrates then goes on to address the question of courage. [358e-]

- "When the courageous fear, their fear is not disgraceful." [360a]

- "Cowardice is ignorance of what is and is not to be feared." [360c]

- "Wisdom about what is and is not to be feared is courage." [360d]

- Potagoras then sums up the discussion.

- "It seems to me that our discussion has turned on us.....'Socrates and Protagoras, how ridiculous you are, both of you. Socrates, you said earlier that virtue cannot be taught - but now you are arguing the very opposite and have attempted to show that everything is knowledge - justice, temperance, courage - in which ccase, virtue would appear to be eminently teachable. On the other hand, if virtue is anything other than knowledge, as Protagoras has been trying to say, then it would clearly be unteachable..... Protagoras maintained at first that it could be taught, but now he thinks the opposite.'" [361a-c]

- The two philosophers then part on convivial terms. [361d-362a]

Symposium

Symposium

This is Plato's poetic masterpiece. It deals with "sex, love and friendship",

mostly between and among men and boys.

The topic is further addressed in Phaedrus and

Lysis.

This is one of my favourite dialogues.

This dialogue relates the events at a formal drinking party held in honour of the tragedian Agathon's first victorious production. The events are presented to us from the point of view of Aristodemus, a comic poet. [172a-173e] To honour the event, Socrates both "bathed and put on his fancy sandals - both very unusual events. [174a] Socrates persuades Aristodemus to attend even though he had not received an invitation [174c] and then hangs back himself, until it is established that Agathon had tried to find Aristodemus to invite him to the party, but had failed to get hold of him in time [174e-175d]. To gratify Phaedrus, who regrets the neglect of Eros, the god of love, characteristic of greek poets; each of the company agrees to give a speech in praise of Eros. Eros encompasses both hetero- and homo-gender attraction and affection, but the focus here is on the adult male's role as educator of the adolescent. [175e-178a]

- Phaedrus' speech. [178b-180b]

- Phaedrus is a passionate admirer of rhetoric. He says that love tends to produce virtuous behaviour out of a desire to appear well to the object of one's affection and a desire not to be ashamed before him.

- "I cannot say what greater good there is for a young boy than a gentle lover; or for a lover than a boy to love." [178c]

- "Besides, no one will die for you but a lover, and a lover will do this even if she's a woman." [179b]

- "Therefore I say Eros is the most ancient of the gods, the most honoured and the most powerful in helping men gain virtue and blessedness, whether they are alive or have passed away." [180b]

- Pausanius' speech. [180c-185c]

- Pausanius is Agathon's lover. He says that there are two kinds of love and that the goddess Aphrodite is dual: Urania and Pandemos.

- "Love is not in himself noble and worthy of praise: that depends on whether the sentiments he produces in us are themselves noble." [181a]

- Pandemos is basically sexual and carnal. The love she favours is vulgar and ignoble. Urania is concerned only with the love of men for adolescent boys. The love she favours is basically intellectual and concerned with the soul. It is heavenly and noble.

- "I am convinced that a man who falls in love with a young man of this age [i.e. an older adolescent] is generally prepared to share everything with the one he loves - he is eager, in fact, to spend the rest of his own life with him." [181d]

- "In .... places .... which are subject to the barbarians .... the love of youths shares an evil repute with philosophy and gymnastics, because they are inimical to tyranny. The interests of such rulers require that their subjects should be poor in spirit and that there should be no strong bonds of friendship or attachments among them, which such love, above all other motives, is likely to inspire. Our Athenian tyrants learned this by experience: for the love of Aristogeiton and the constancy of Harmodius had a strength which undid their power.

- "Our customs, then, provide for only one honourable way of taking a man as a lover.... we allow that there is one.... reason for willingly subjecting oneself to another.... for the sake of virtue." [184c]

- "When a lover and a youth come together and.... the lover realizes that he is justified in doing anything for the youth who grants him favours, and when the youth understands that he is justified in performing any service for a lover who can make him wise and virtuous.... then, and only then.... is it ever honourable for a youth to accept a lover." [184c-d]

- "Eros' value to the city as a whole and to the citizens is immeasurable, for he compels the lover and his beloved alike to make virtue their central concern." [185c]

- Eryximachus' speech. [185d-188e]

- Eryximachus is a physician and scientist. He says that love is not simply characteristic of the human soul but "occurs everywhere in the universe.Love is a deity of the greatest importance: he directs everything that occurs." [186b]

- "What is the origin of all impiety? Our refusal to gratify the orderly kind of Love, and our deference to the other sort, when we should have been guided by the former sort of Love in every action...." [188c]

- "Such is the power of Love... even so it is far greater when Love is directed, in temperance and justice, towards the good; whether in heaven or on earth. Happiness and good fortune, the bonds of human society, concord with the gods above - all these are among his gifts." [188d]

- Aristophanes' speech. [189a-194e]

- Aristophanes is a comic poet. He says that ".... people have entirely missed the power of Eros.... For he loves the human race more than any other god; he stands by us in our troubles, and he cures those ills we humans are most happy to have mended." [189c-d] This language is echoed in many texts of the Greek Orthodox Liturgy.

- He tells a fable of the origination of human love in terms of the splitting up of spherical whole beings who dared to attack the gods [in effect, committing "original sin"].

- "Now, since their natural form had been cut in two [cf Eve being created from Adam's rib], each one longed for its own other half, and so they would throw their arms about each other, weaving themselves together, wanting to grow together.... Then, however, Zeus took pity on them.... he moved their genitals around to the front.... the purpose of this was so that when a man embraced a woman, he would cast his seed and they would have children; but when a male embraced male, they would at least have the satisfaction of intercourse.... This then is the source of our desire to love each other. Eros is born into every human being; it calls back the halves of our original nature together; it tries to make one out of two and heal the wound of human nature....

- "And so, when a person meets their other half.... something wonderful happens: the two are struck from their senses by love; by a sense of belonging to each other, and by desire, and they don't want to be separated from each other, not even for a moment. These are the people who finish out their lives together.... No-one would think .... that mere sex is the reason each lover takes so great and deep a joy in being with the other." [192c-d]

- "Suppose ... Hephaestus ...asks them ... 'Is this your heart's desire, then - for the two of you to become parts of the same whole .... I'd like to weld you together and join you into something that is naturally whole, so that the two of you are made into one' .....no one who received such an offer would turn it down... everyone would think that he'd found out at last what he had always wanted: to come together and melt together with the one he loves, so that one person emerged from two... Love is the name for our pursuit of wholeness, for our desire to be complete." [192d-e]

- "I say there is just one way for the human race to flourish: we must bring love to its perfect conclusion; and each of us must win the favours of his very own youth, so that he can recover his original nature.... Eros promises the greatest hope of all: if we treat the gods with due reverence, he will restore to us our original nature, and by healing us, he will make us blessed and happy." [193c-d]

- Agathon's speech. [194e-197e]

- Agathon, the party's host, is a dramatist and hence a master of words. He gives a speech "part of it in fun and part in moderate seriousness" [198a] extolling the virtues of Eros.

- He claims that Eros is:

- forever young and hates old age. [195b]

- delicate and gentle and eschews harshness. [195d-e]

- fluid and supple of shape, graceful and of great beauty; continually at war with ugliness. [196a-b]

- opposed to injustice and violence. [196b]

- moderate, because he is the strongest of all the passions. [196c]

- brave: for the same reason! [196d]

- wise, a poet and an accomplished artist. [196e]

- the producer of animals. [197a]

- the teacher of artisans and professionals. [197a]

- the settler of all the disputes of the gods. [197b]

- our saviour. [197e]

- Socrates comments that this speech was very beautifully worded. [198b-c] He says, ironically, how foolish he is to think "that you should tell the truth about whatever you praise."[198d]

- Socrates points out that love is not obviously an absolute, but rather is relative to a desired object. [199c-201a]

- He then points out that love cannot be beautiful or good, for love desires beauty and good, which therefore it cannot possess of itself, [201a-c] Agathon agrees, and admits "I didn't know what I was talking about in that speech." [210c]

- Socrates comforts him by saying again that it was nevertheless a beautiful speech. [201c]

- Socrates' speech. [201d-212c]

- Socrates gives his own speech over to reporting a discourse on love that he heard from a wise woman called Diotima.

- He says that he had spoken much as Agathon and had been refuted by Diotima in just the way that he has just refuted Agathon.

- She then pointed out that Eros cannot be a god as it is need of what it desires. [202a-d] She suggests that Eros is a "great spirit", one of the "messengers who shuttles back and forth between [heaven and earth] conveying prayer and sacrifice from men to gods, while to men they bring commands from the gods and gifts in return for sacrifices." [202e] The Roman Canon of the Mass has a prayer invoking just such an "angel".

- She characterizes Eros as being intermediate between virtue and vice. [203b-204b]

- "Eros .... is in love with what is beautiful, and wisdom is extremely beautiful. It follows that Eros must be a lover of wisdom...." [204b]

- She says that the purpose of possessing good and beautiful things is to attain happiness. [205a]

- She says that love for the good can be either mediated through many lesser goods or be directly addressed to what is ultimately good and beautiful. [205a-d]

- "What is it precisely that [lovers] do? .... It is giving birth in beauty, whether in body or soul" [206b]

- "What Love wants is not beauty.... but reproduction and birth in beauty.... because reproduction goes on forever; it is what mortals have in place of immortality." [206e]

- She says that men and women also live on the memories of those who loved them. [208c]

- She then says that some folk primarily seek immortality through physical offspring, while the more noble seek immortality through artistic creativity or - best of all political philosophy. [209a-b]

- She says that such are drawn to handsome youths "if he also has the luck to find a soul that is beautiful and noble and well formed, and is even more drawn to this combination; such a man makes him instantly teem with ideas and arguments about virtue... and so he tries to educate him.... such people.... have much more to share than do the parents of human children, and have a firmer bond of friendship, because the 'children' in whom they have a share are more beautiful and more immortal.... Even you, Socrates, could probably come to be initiated into these rites of love; but as for the purpose of these rites.... that is the final and highest mystery, and I don't know if you are capable of it." [209c-210a]

- She explains how it is necessary to perceive beauty in itself beyond the beauty of things; even the beauty of the human soul. [210b-211a]

- "So when someone rises by these stages, through loving boys correctly, and begins to see this beauty, he has almost grasped his goal.... one goes always upwards, for the sake of this beauty: starting out from beautiful things.... to all beautiful bodies, then .... to beautiful customs.... to learning beautiful things.... and from these lessons he arrives in the end at this lesson, which is learning of this very Beauty, so that in the end he comes to know just what it is to be beautiful." [211c-d]

- "But what.... if man had eyes to see true beauty - divine beauty, I mean, pure and dear and unalloyed, not clogged with the pollutions of mortality and all the colours and vanities of human life - thither looking, and holding converse with true beauty simple and divine? Do you think it would be a poor life for a human being to look there and to behold it by that which he ought, and be with it? Remember how.... in that communion only, beholding beauty with the eye of the soul, he will be enabled to bring forth, not images of beauty, but realities (for he has hold not of an image but of a reality), and bringing forth and nourishing true virtue to become the friend of God and be immortal, if mortal man may." [211e-212a]

- Alcibiades' speech. [212c-222c]

- Alcibiades who used to be Socrates' beloved youth now gate-crashes the party. He proposes to give a speech in praise of Socrates, though he makes it plain that he is no longer a sincere admirer. [212c-215a]

- "When he starts to speak, I am beside myself: my heart starts leaping in my chest, the tears come streaming down my face... nothing like this ever happened to me [no-one else ever] upset me so deeply that my very own soul started protesting that my life was no better than the most miserable slaves.... So I refuse to listen to him.... for, like the Sirens, he could make me stay by his side till I die....

- He goes on to praise Socrates' military exploits. [220b-221d]

- He then praises Socrates method of argument. [221e-222a]

- "He has deceived us all: he presents himself as your lover, and before you know it, you're in love with him yourself! I warn you, Agathon, don't let him fool you! Remember our torments; be on your guard: don't wait .... to learn your lesson from your own misfortune." [222b-c]

Therefore, the ill-repute into which these attachments have fallen is to be ascribed to the poor character of those who condemn them: that is to say, to the self-seeking of the governors and the cowardice of the governed. On the other hand, the indiscriminate honour which they are given in some countries is attributable to the mental indolence of their legislators.

In our own country a far better principle prevails, but .... its description is not straightforward. For open loves are held to be more honourable than secret ones, and the love of the noblest and highest sort of person, even if they are not so handsome, is especially honourable." [182b-d]

That is why a man who is split from the double sort .... runs after women. Many lecherous men have come from this class, and so do the lecherous women who run after men. Women who are split from a purely female original, however, pay no attention to men; they are oriented more towards women, and lesbians come from this class. Men who are split from a purely male original are male-oriented.... those are the best of boys and youths, because they are the most manly in their nature." [191a-192a]

My whole life has become one constant effort to escape from him and keep away... sometimes I think I would be happier if he were dead, and yet I know that if he dies I'll be even more miserable. I can't live with him, and I can't live without him!....

He is crazy about beautiful boys; he constantly follows them around in a perpetual daze. Also he likes to say that he is ignorant... his whole life is one big game... I once caught.... a glimpse of the figures he keeps hidden within: they were godlike.... I just had to do whatever he told me.

What I thought at the time was that he really wanted was me.... I had a lot of confidence in my looks.... My idea, naturally, was that he'd take advantage of the opportunity.... but no such luck!.... Socrates had his usual sort of conversation with me, and at the end of the day he went off!...

I got nowhere.... I managed to persuade him to spend the night at my house.... I said... 'It would be really stupid not to give you anything you want...'

I slipped underneath the cloak and put my arms about this man - this utterly un-natural, this extra-ordinary man - and spent the whole night next to him.... But.... this hopelessly arrogant, this unbelievably insolent man turned me down!

I was deeply humiliated, but also I couldn't help admiring his natural character, his moderation, his fortitude - here was a man whose strength and wisdom went beyond my wildest dreams!... I couldn't bear to lose his friendship... I had no idea what to do, no purpose in life; ah, no one else has ever known the real meaning of slavery!" [215e-220a]

Republic

Republic

This is Plato's epic work. It consists of ten "books", each as large as

a typical dialogue. Its overall topic is Justice. It is famous for containing

a description of the Ideal State, its governance (by an aristocracy of

Philosopher-Magistrates) and constitution. This is mostly of theoretical

interest. As a blue-print for a real State it is entirely impractical,

because it makes no allowance for human instincts and in particular "the

family unit" and romanto-erotic love. This is surprising given the

emphasis that Plato elsewhere places on eroticism

as a sound (while not the best) foundation for philosophical training.

- Book I

- The nature of Justice is discussed. Cases are made for Justice being:

- The doing good to friends and evil to enemies [331e-335e].

- "Can those who are just make people unjust through justice? .... it has become clear to us that it is never just to harm anyone." [335c,e]

- The advantage of the stronger "Might is Right" [338c-350e].

- Defending this position, the sophist Thrasymachus argues that: "No craftsman, expert or ruler ever errs at the moment when he is ruling.... A ruler, insofar as he is a ruler, never makes errors and infallibly decrees what is best for himself, and this his subjects must do." [341a]

- Both are rejected emphatically. It is countered that:

- ".... justice brings friendship and a sense of common purpose." [351d]

- "First, injustice makes even a single individual incapable of achieving anything, because he is in a state of civil war and not of one mind; second, it makes him his own enemy, as well as the enemy of just people." [352a]

- "... a just person is the friend of the gods."[353b]

- Instead, it is argued that justice is a virtue of the soul [353e] and that

- Book II

- Socrates' teaching is challenged [357a-367e].

- It is argued that :

- Justice is onerous [358a-359c].

- Justice is only valued because of the advantage of the good reputation that it gives the just man, but it is even more advantageous for the unjust man to be thought to be just [359d-361d].

- For justice to be valuable in itself, it must be demonstrated that this is true even if the just man is thought by his fellows to be unjust [362e-363e].

- It is the cunning and wicked who generally succeed in living successful and happy lives [363e-364a].

- The gods do not care about justice, for they can be propitiated by sacrifice [364b-366b].

- It is therefore necessary to decide exactly what justice is, rather than relying on any common-sense view of the matter [366c-367e].

- Socrates responds by suggesting that the topic of Justice should be pursued on a larger scale, in terms of the ordering of a community of citizens [368a-369d].

- He suggests that in a city it is best for each individual live "minding his own business on his own" [370a] for in this way each will contribute to the whole in accordance with his native talent [369e-373d].

- He suggests that there is a need for governors that are both "spirited" and "gentle", like well trained guard dogs [373e-377a].

- He suggests that in a healthy society, theological myths must be censored to ensure that injustice is never attributed to the gods [377b-385c].

- Book III

- Socrates continues his proposals for the constitution of the ideal state. He insists upon the control of information and the arts: censorship and propaganda. [386-401c]

- He than discusses the kind of myths that should be promoted in the State [386a-392c] in order that “future generations should not …. take their friendship with one another lightly.” [386a]

- "If it is appropriate for anyone to use falsehoods for the good of the city.... it is the rulers. But everyone else must keep away from them...." [389b]

- “We certainly won't …. allow it to be said that …. any hero and son of a god dared to do any of the terrible and impious deeds that they are now falsely said to have done. We'll compel the poets either to deny that the heroes did such things, or else to deny that they were children of the gods. They mustn't say both, or attempt to persuade our young people that the gods bring about evil or that heroes are no better than humans. As we said earlier, these things are both impious and untrue, for we demonstrated that it is impossible for the gods to produce bad things.” [391d-e]

- “We'll agree about what stories should be told about human beings only when we've discovered what sort of thing justice is and how by nature it profits the one who has it, whether he is believed to be just or not.” [392b-c]

- He then discusses style in drama, music, painting and sculpture. [392c-403c]

- “If a man, who through clever training can become anything and imitate anything, should arrive in our city, wanting to give a performance of his poems, we should bow down before him as someone holy, wonderful and pleasing; but we should tell him that there is no one like him in our city and that it isn't lawful for there to be. We should pour myrrh on his head, crown him with wreaths, and send him away to another city. But, for our own good, we ourselves should employ a more austere and less pleasure giving poet and storyteller, one who would imitate the speech of a decent person….” [398a-b]

- “…. we rather seek out craftsmen who are by nature able to pursue what is fine and graceful in their work, so that our young people will live in a healthy place and be benefited on all sides, and so that something of those fine works will strike their eyes and ears like a breeze that brings health from a good place, leading them unwittingly, from childhood on, to resemblance, friendship and harmony with the beauty of reason.” [401b-d]

- “If someone's soul has a fine and beautiful character and his body matches it in beauty and is thus in harmony with it, so that both share in the same pattern; wouldn't that be the most beautiful sight for anyone who has eyes to see?” [402d]

- “…. if a lover can persuade a boy to let him, then he may kiss him, be with him, and touch him – as a father would a son – for the sake of what is fine and beautiful, but – turning to the other things – his association with the one he cares about must never seem to go any further than this….” [403b]

- Socrates next briefly considers the regime of physical training. [404d-e]

- He passes on to discuss the practice of law and medicine. [405a- 410b] He argues that medicine that simply prolongs life without effecting a cure is inappropriate.

- “It isn't possible for a soul to be nurtured among vicious souls from childhood, to associate with them, to indulge in every kind of injustice, and come through it able to judge other people's injustices from its own case; as it can diseases of the body. Rather, if it is to be fine and good, and a sound judge of just things, it must itself remain pure and have no experience of bad character when it's young. That's the reason, indeed, that decent people appear simple and easily deceived by unjust ones when they are young. It's because they have no models in themselves of the evil experiences of the vicious to guide their judgements….. Therefore, a good judge must not be a young person but an old one, who has learned late in life what injustice is like and who has become aware of it not as something at home in his own soul, but as something alien and present in others, someone who, after a long time, has recognized that injustice is bad by nature, not from his own experience of it, but through knowledge.” [409a-b]

- “… as for the ones whose bodies are naturally unhealthy or whose souls are incurably evil, won't they let the former die of their own accord and put the latter to death?” [410a]

- He then argues that education should be designed to balance the intellect, emotions and appetites. [410b-412b]

- He than discusses who should rule in the State. [412c-417b] He argues that they should be those who can identify with the good of all and who are tenacious in holding on to what is true and just. He divides the rulers into two classes: the guardians and the auxiliaries.

- "Someone loves something most of all when he believes that the same things are advantageous to it as to himself, and supposes that if it does well, he'll do well, and that if it does badly, then he'll do badly too." [412d]

- "Isn't being deceived about the truth a bad thing, while possessing the truth is good?" [413a]

- He tells a fable designed to inculcate a sense of corporate identity. [415a-d]

- He insists that it is absolutely necessary that the guardians and auxiliaries are given a good education in order to equip them for their roles [416a-d] and also that they hold their goods in common. [416d-417b]

- Book IV

- Socrates suggests that both affluence and poverty corrupt people [421d-422a], and that a state that is at peace with itself is many times more effective for its size than one that is riven by envy and conflict [422b-423b].

- He says that the basis of right conduct is a good education and upbringing

- "If by being well educated they become reasonable men, they will easily see these things for themselves …. That marriage, the having of wives, and the procreation of children must be governed as far as possible by the old proverb: 'Friends possess everything in common.'" [423e]

- "Those in charge must cling to education and see that it isn't corrupted without their noticing it, guarding it against everything. Above all, they must guard as carefully as they can against any innovation in music and poetry or in physical training that is counter to the established order." [424b]

- Socrates says that once the basic laws have been laid down, it is not right to enact detailed regulations regarding private contracts and business affairs etc.

- "It isn't appropriate to dictate to men who are fine and good. They'll easily find out for themselves whatever needs to be legislated about such things….. If not, they'll spend their lives enacting a lot of other laws and then amending them, believing that in this way they'll attain the best." [425e]

- Socrates disclaims any expertise on religious matters and assigns responsibility for such matters to the Delphic Oracle [427a-c].

- Socrates seeks to identify in what way a city might be said to be "wise, courageous, moderate and just" [427e]. These four virtues are characteristic of Platonism.

- Wisdom is identified with knowledge, especially of how to govern [428b-e].

- Courage is identified with a species of faith [429a-430c].

- "Courage is a kind of preservation …. Of the belief that has been inculcated by the law through education about what things and sorts of things are to be feared …. Preserving it and not abandoning it because of pains, pleasures, desires or fears." [429d]

- Moderation is identified with a species of love. It consists of harmony or right relationship between the various parts of the state [430d-432b].