Introduction

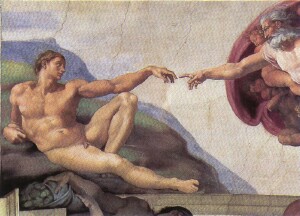

As I start to write this paper, I intend to cover the vast field of "Human Free-Will", and "God's Grace". This is notoriously difficult territory, and I am reticent to put forward my own solution. I hope that however misguided and inadequate it turns out to be, that it may be of some help in pointing the way for those that follow. I would like to thank my friends "DC" and "PG" for stimulating some of the discussion. I feel that I have had a number of unexpected insights while writing this document. In as far as these are due to the guidance of Holy Spirit I wish to thankfully attribute all responsibility to God, rather than my own ingenuity.What is Life?

In a previous paper, I have argued that life is an entirely natural (i.e. physical or material) phenomenon that inevitably emerges in non-linear dynamical systems. It is not necessarily biological in basis.Consciousness and the Soul

I also argued there that the old "Mind/Body question" is wrongly posed. I am an objective realist, and reject the idea that mind is prior to matter, and that the latter is nothing more than the imaginings of mind. I believe (though not dogmatically) that mind is entirely derivative of matter: that Mind is a kind of higher order life, living "on top of" unthinking life; symbiotically - though potentially parasitically! The corporate life of the ant nest or human state is best described as "mental". However, I do not accept that "this is all there is to be said".Mind and Consciousness

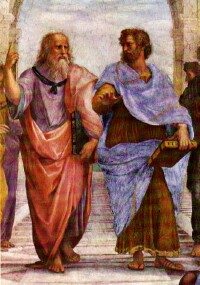

Elsewhere, I contend that "mind" and "consciousness" are not the same concept at all. My mind is an attribute of my nature, just as is my hand. I use either to effect certain actions. I grasp a hammer with my hand. I grasp a concept with my mind. My mind is no more my self than is my foot or ear or eye or liver. My self is my consciousness, my awareness, my person: a point of reference on which everything else is hung. On the one hand, as a Platonist, I find the idea that my self is the abiding patterning (or form) of my mind attractive. On the other hand, I see no connection between such a patterning and my experience of consciousness, which is the issue at stake. To a degree I don't need to argue for the distinction between consciousness and mind. It is well recognized that one is unconscious of much of one's mental activity: hence the term "unconscious mind". Although, an account of consciousness that makes it a property of part of the mind is formally possible, I am not interested in this: because it makes no connection with my own experience of consciousness.I find it quite impossible to express what I mean by consciousness. The best I can do is to try and elicit a reaction of recognition from anyone that I discuss this matter with. It is all to do with words like "I", "me", and "mine", closely related to the words "self", and "aware" and to a lesser extent "know" and "feel" (for me these last words are suspiciously related more to Mind rather than Consciousness). I suspect that a living thinking being that was not conscious would not have need of such words. The passive grammatical form would always suffice, there being no awareness to hang a sense of causality upon.

Note that I am not stressing self-consciousness in this discussion. I don't think the distinction between consciousness and self-consciousness is at all important. Once an entity is conscious, becoming conscious of its self is just a (fascinating) technical matter of self reference. Without a self to be conscious of and a consciousness to be conscious with, one cannot be self-conscious. The former two constitute the latter one: nothing else is required. It occurs to me that "the self" might be a good name for the model idea of the mind that the mind has of the mind, but I can't envisage how this model idea could be any more "aware" than any other one!

What is Free-Will?

I do not think that the problem of Free Will is either particularly difficult or interesting. For me the difficulty is in discussing (still more solving!) the problem of Consciousness. As I have already mentioned, I think that the two are related. Consciousness is the hook that serves to anchor one's sense of causality. I contend that it is this sense of causality which we informally refer to with the phrase "Free Will". It may be that Consciousness has an active role, as a cause: but this as yet remains to be demonstrated. The alternative is that Consciousness is entirely passive: being informed by what the mind perceives, but not influencing the mind's activity.Stating the Problem

The classical problem of Free Will [D.J. O'Conner, Macmillan 1971] can be posed in the following psychological terms. It would seem that Free Will cannot exist: for either everything that I do is determined by my past and present experience; or else it is not. If it is, I have no Free Will: for my action is fixed by external forces; if it is not then any "Free Will" I have is indistinguishable from random behaviour: which is of no value and not at all what one naively means by Free Will!A second version of the problem is the (Meta-)Physicist's difficulty. For him all action has a cause. In a naive Newtonian style mechanics, causes exactly pre-determine effects and events. In a dualistic particle-wave Quantum Mechanics, causes do not pre-determine effects, but only the probabilities of events. In the former case, Free Will is excluded by mechanistic determinism: in the latter case, by a statistical break-down of causality. While these two versions of the problem are not identical, I suspect they are equivalent. I shall now argue that both syllogisms are invalid.

Causality and Determinism

I contend that the key to the problem lies in clearly distinguishing between the words "cause" and "determine". In common speech these are synonyms; but in philosophic use, Popper has made clear ["Indeterminism in Quantum Physics and in Classical Physics", Brit J. Phil. Sc. I (1951-2) p189] that a valid distinction can be drawn. To physically determine something is to fix it either before-hand in time or remotely in space, with full knowledge of what one is achieving and to any degree of precision, in principle. To metaphysically cause something is quite different from this and a much weaker (but more important!) concept. To be the cause of something is to be that which a contingent thing's being can be traced to as its origin: that without which it would not be what it is. There is no need that any degree of knowledge (including ultimate exactitude!) of the cause should determine the effect, except in the trivial sense of following the sequence of events to see what in fact happens!The Magnetic Pendulum

It is generally characteristic of linear Newtonian Mechanics that all causes are determinist: it is a simple matter to project from initial or boundary conditions to temporally or spatially remote results. I give an account of an exception elsewhere. This is related to a result in mathematical physics called Liouville's Theorem, which states that the degree of indeterminacy of a system's configuration remains the same as time proceeds. As soon as non-linearities are envisaged, this characteristic fails. The asymptotic result of any cause becomes indeterminate, no matter how accurately that cause is initially specified. A simple and evocative example is the magnetic pendulum. Consider a standard pendulum whose bob is a lump of soft iron. Place beneath it a horse-shoe magnet, such that the two poles lie in a horizontal plane just below the lowest point that the bob can reach, with the body of the magnet symmetrical about the vertical dropped from the point of support of the pendulum.Obviously, the bob has two possible points of lowest potential energy. Each is close to one or other of the magnetic poles. They can be labelled "North and South". If allowed to come to rest the bob is "equally likely" to end up in either of these positions. Every static initial position (in [q,f] space) of the pendulum bob can be labelled in terms of which final resting state (North or South) it results in. It turns out that; contrary to all common-sense expectations; there are large regions of [q,f] space for which regions of Northness are interpenetrated by smaller regions of Southness which are interpenetrated in turn by even smaller regions of Northness and so on indefinitely. This is an example of "fractal" or "chaotic" physics and is common to all non-linear systems (i.e. all real systems). Although the simple equations of Newtonian Physics govern the behaviour of the bob at every instant, the end result is not determined by any level of accuracy to which the initial conditions are specified!

This is nothing to do with random air movements, Brownian Motion, the microscopic variability of viscosity or Quantum Mechanics. All these would exacerbate the problem in practice; but even when the pure Newtonian system is modelled with ultimate numerical accuracy, the type of behaviour I have described results. In mathematical physics terms, not only do the non-linearities subvert Liouville's Theorem (and so the "volume of uncertainty in phase space" grows exponentially with time), but what may have started out as a compact region of phase space uncertainty rapidly elongates and tangles into a complicated knot.

Ubiquitous Radical Indeterminacy

At first, when the magnetic pendulum is released, its phase-space trajectory is predictable. Tiny changes in its initial conditions produce equivalently tiny changes in its subsequent motion. However, as it is a non-linear system, this behaviour cannot continue. At some point, its trajectory ceases to be well defined by the initial conditions: the accuracy to which these have to be specified in order to have a good idea of what the system's motion will falls to zero: ultimate and unattainable precision. In effect, what up until a certain point had seemed to have been a single phase-space trajectory: at that point revealed itself to have been an indefinitely tight bundle of trajectories. From that point onwards, this bundle unravels and its constituent trajectories diverge rapidly. So rapidly, in fact, that they soon lose any semblance of similarity. One might presume that reality is described by only one of these trajectories, but another possibility is that reality is infinitely pleural and every possibility is substantiated.The point on the trajectory at which bundle unravelling occurs is itself not subject to prediction. Moreover, there is not just one such point but rather a superfluity of them. Every apparent single trajectory continually resolves itself into more and more trajectories which themselves further resolve themselves: ad infinitum. The simple fact is that for even very simple non-linear classical systems, causal laws do not determine outcomes! There is a radical indeterminacy in all but the simplest Newtonian systems.

Classical Indeterminism vs Quantum Uncausality

This indeterminacy is compounded in conventional Quantum Mechanics: where the laws of physics cease to be causal. I decry this apparent break-down in causality and hope that at some point it will be possible to re-establish the principal of causation within Quantum Mechanics. I do not wish to invoke this breakdown in causality as a crack in physics through which to insinuate Free-Will. For me, it is a carbuncle on the ontological face of contemporary Physics. It should be noted that even if quantum causality is eventually re-established (as I hope that it will be), this will have no effect on classical indeterminism.It should be noted that while my account of phase-space trajectory-bundle unravelling is superficially similar to the "Multiverse" interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, it is not a Quantum Mechanical theory or interpretation at all: but rather an account of classical Newtonian Dynamics.

The Will

I suggest that the Will (free or not) is that which decides, given data or evidence, what is the appropriate conclusion to be drawn and or action taken. The Reason plays a part in this decision by elucidating the dependencies of facts based on logic and background hypotheses. No reasonable person wants a "Free Reason": the only virtue of reason is its abject slavery to premises and logic! I further suggest that in almost every case there is no "right answer". Goedel's famous theorem tells us that we must expect not to be able to arrive at all propositions that are true by a process of deduction. Moreover, in ethics, the evidence is incommensurate, the problem space multi-dimensional. To decide what is appropriate involves a metric that combines the diverse inputs into a single evaluate. This metric is necessarily subjective. Moreover, it is plausible that it will be (and certainly should be!) plastic: subject to modification as a result of experience.Imagine the very simplest case, where some automaton has a very limited number of simple senses, each characterized by a few variables, and where its only objective is to maximize one of these by changing its location on a one-dimensional track. In any situation it is faced with the binary choice of moving forward or backward. It has to combine or process its inputs in some way in order to decide which way to move. This processing is the exercise of its will. At any moment, it will have some prescription (initially a very simple one) for processing the available input data (past and present) to generate an output that drives its servo-motor and so moves it either backwards or forwards. Ideally, the automaton should have the ability to modify this metrical formulation: perhaps randomly, perhaps also according to some other prescription. If the automaton is able to evaluate successive formulations (according to some other metric, which may itself be plastic) and so choose to rely on (and use as a basis for developing others) the one that it identifies as superior: then one might expect that over time it will evolve a prescription that is generally successful in gaining its objective within a stable environment.

My Solution to the Problem

Given its whole past history of experience, and the possibility that at least some of the modifications made to its "will" were generated randomly: the end result will be quite impossible to determine. At every point, the way in which the automaton reacted to the stimuli it was presented with was caused (and determined) by its prevailing internal state and the stimuli themselves, but it would be quite impossible to pre-determine its eventual behaviour. In any reasonable use of the words, such an automaton has Free-Will.- It makes rational decisions,

- based on a system of subjective prejudices or metrics

- that themselves are subject to variation

- according to its own evaluation of its experience.

I suggest that whenever I make a decision, the phase-space trajectory-bundle of my brain (otherwise known as my mind) resolves itself (in other words: "I make my mind up") just as the magnetic pendulum-bob comes to rest over either the North or South pole: though when it was released the initial [q,f] conditions gave no clue as to where its destiny lay.

The question still arises, how is it that one trajectory "wins out" over all the others? Is this caused or random? In effect, our original dilemma is still not answered - or is it? I suggest that from the perspective we have now gained, the question does not have the force it did originally. We are now in a position to simply reply "yes" and smile. The dichotomy proposed has been shown to be false.

- The outcome of any mental act is

- as are all non-linear processes

- totally caused and entirely rational

- within the limitations of doxa as opposed to episteme

- and yet utterly indeterminate.

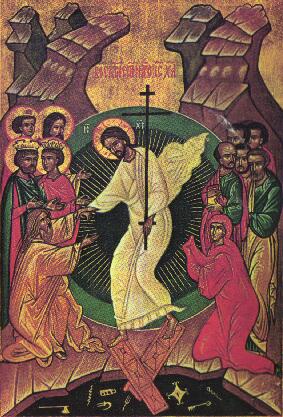

Another possibility that may bear consideration is that of "reverse causality". We have no difficulty in thinking of God "starting the Universe off" from well-defined initial conditions, well then: what is to stop God also insisting that "the Universe finishes up" in an equally well-defined destiny. God is both Alpha and Omega, after all! This would uniquely define the exact single phase-space trajectory of the State Vector of the whole Universe.

Moreover, it is good theology to say that God's creative action is continuous: not restricted just to the start of time (if this means anything). Perhaps then it is best to say that God acts at each point of trajectory-bundle unravelling to determine which motion is in fact substantiated. Perhaps the revelation that the Universe is "open to determination" at every moment of its evolution is another manifestation of - and so argument for - God's creative activity.

In this way, every mental outcome is determined by God while being the result of Human Free-Will, with no contradiction or conflict between these two statements.

Does Consciousness help?

As

I've already mentioned, Consciousness might play a merely passive, observational

role only. I don't think that this is a sustainable position, however.

It seems to me that because I am now writing about my Consciousness,

my mind must be informed of the existence of my Consciousness: and

if so, my

Consciousness is active in effecting such information; if in

no other regard! Hence, I conclude that my Consciousness has some kind

of active role as a Deliberative Rational Agent.

As

I've already mentioned, Consciousness might play a merely passive, observational

role only. I don't think that this is a sustainable position, however.

It seems to me that because I am now writing about my Consciousness,

my mind must be informed of the existence of my Consciousness: and

if so, my

Consciousness is active in effecting such information; if in

no other regard! Hence, I conclude that my Consciousness has some kind

of active role as a Deliberative Rational Agent.

It would now seem attractive to identify my Consciousness with the Free Will that I think I have: but I can see no way to do so. Once more, there is no obvious connection between my subjective experience of Consciousness (and the fact that I say experience of Consciousness itself suggests that my Consciousness is actively engaged with my mind) and the elaborate (but naive) description I have given of a plausible objective reality: my Free Will. Moreover, I do not see the need to invoke Consciousness to explain Free Will, because I believe that I have already given an adequate account of Free Will without having had cause to involve Consciousness.

The main problem with my account of Free Will is that, apart from the possibility of occasional randomness, it leaves no place for the common sense view that Free Will amounts to the idea that whenever in fact I chose to do something, I could have chosen to do something else. This objection is difficult to evade, but just as difficult to understand. The meaning of the word could is the problem here. In my theory of Free Will, the only sense admissible is that: if some random part of the process had happened to play a pivotal role, then indeed the actual choice could have gone in a number of ways: as determined by the random contribution to my decision metric. This does not seem to be satisfactory, however. It makes the could into a possibility devoid of any significance: just a random variable. On the other hand, if randomness is rejected as a contribution to the decision metric, then it is difficult to see how my choice could possibly have been different from what it was! If there was no random element, then what could cause me to make a different choice?

If my Consciousness is allowed a causal input to the process [C.A. Campbell "In Defence of Free Will" (1967)], the problem still does not resolve itself. Either the state and behaviour of my Consciousness (if this is to be distinguished from that of my Mind) is itself caused, or it is not. If not, then it is random: could have affected my decision, but is no help in elucidating the meaning of Free Will and deliberate choice. If it is caused, then any decision that I make must once more have been inevitable and could not have been other than it was.

The problem isn't quite as bad as I make out. I have already established that sometimes the cause required to produce a macroscopic effect is physically negligible and plausibly mathematically infinitesimal. Hence our difficulty isn't so much one of choosing between the intrinsic determinism of physics and an extrinsic randomness: the two classical enemies of Deliberative Free Will. Our difficulty lies in conceiving how, when the complex non-linear system that is our Brain-Mind ever resolves its state into unambiguous choices, its state can have any significance relative to objective reality. This is because it seems that it is determined by mathematically vanishing and so insignificant causes. We seem to have the situation that inconsequential and perhaps truly vanishing events have become consequential causes! How can this characteristic of physics be distinguished from mere capriciousness? There is no difficulty in finding room for extraneous influence, as attributed to the Consciousness by Professor Campbell. Moreover, the same kind of analysis may itself applied to the Consciousness: opening it also up to the possibilities of radical Indeterminism.

I tend to the view that to analyse Free Will in terms of "could have done something else" is misconceived. Free Will is more related to personal integrity and the absence of external intimidation or coercion than to "could haves" or the existence of alternative possibilities [T. Hobbe: "Leviathan" Ch 21, D. Hume: "Treatise of Human Nature" and "Inquiry concerning the Human Understanding"]. However, this theory is incomplete: for it doesn't explain the difference between a benign external influence and coercion. Both could cause me to change my behaviour. The former is unobjectionable, the latter wicked. Bribery and hypnotism are arguably forms of coercion, yet neither involves the prospect of threat. Somehow, one recognizes that it is not "fair" to hypnotize or bribe someone, hardly less so than to torture or blackmail them. To do either is to impinge on their autonomy and to derogate from their freedom.

Morality

Now

that I have discussed Free-Will, I shall next address the question of the

manner and context in which it is exercised.

Now

that I have discussed Free-Will, I shall next address the question of the

manner and context in which it is exercised.

The Aristotelian view of man's moral dilemma (now largely adopted by the Church) is one of conflict between the "higher nature" (the spirit) and the "lower nature" (the flesh). Whereas the flesh desires instant gratification of its transitory urges and passions, the spirit aspires to values that are eternal and Divine. The role of the will is to regulate the fleshly passions and control them so that they are properly oriented towards goals set by spiritual values. This exercise of the will is called "self-control" and is supposed to be a skill acquired by continued practice. This view is apparently espoused by St Paul. It is opposed with much conviction and exuberance by the poet William Blake.

Original Sin.

To this basic recipe of internal conflict in man, the Church adds the concept of "post fall concupiscence". In my essay on The Fall, I present the basic Catholic doctrine that original sin is nothing more than a loss of original justice. Typically, however the additional idea, that human nature has been damaged by original sin in such a way that its natural appetites orientate it towards actual sin, features in both protestant and catholic theology. This is called concupiscence, and is a core aspect of the Lutheran view of original sin, which tended to identify the effects of original sin with an essential corruption of human nature (called utter depravity), such that its appetites are entirely distorted and misdirected from their proper ends. This view is motivated by the very real experience of internal conflict that St Paul testifies to and is, I suspect, common to all humankind. In the Apostle's immortal words, "The good that I approve of: I do not; the evil that I disapprove of: that I do" [Rom 7:19]. The Church recommends asceticism (e.g. fasting, flagellation, obedience, poverty, celibacy) as aids to building up the "strength of the will" to resist the blandishments of "the World, the Flesh and the Devil", on the basis that if one forms sufficient "will-power" by imposing at first trivial and then more serious pain upon one self, then one will be equipped to resist external temptations to self-serving pleasure, when these come along.

If

it feels good, it must be bad.

If

it feels good, it must be bad.

In the most extreme (but too common) application of this paradigm, all

that is pleasurable and desirable is seen as being sinful and wrong, and

only that which is painful and repulsive as being good. This can even be

taken to the limit that it is necessary to not only "deny one self" but

also to "destroy one self" and "become the slave of God", giving up all

independence of thought and freedom of will. An insatiable appetite for

self-destruction and the elevation of obedience above (or equation with)

charity as the greatest of virtues is the inevitable result. The Church

has condemned the greatest excesses of this paradigm as "Jansenism",

and popularized devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus as the great remedy

against it; but large elements of even the post Vatican II "conservative"

establishment (e.g. Opus Dei) still push and popularize aspects of this

"suicidal" formula of self mortification.The Platonic View

The Platonist view is very different. It is entirely gentler and more optimistic of human nature. The analysis of the moral dilemma is not in terms of "will-power" (to which it is difficult to give any meaning) but in terms of understanding and knowledge. The Platonic contention is that any rational person who knows what is good, will necessarily do what is right, because they cannot possibly desire to do anything else.Vice is contrary to the Nature of Man as Man; for it is contrary to the order of Reason, the peculiar and highest principle in Man. Nor is anything in itself more unnatural or of greater deformity in the whole world than that an Intelligent Agent should have the Truth of Things in his Mind and that it should not give Law and Rule to his Temper, Life, and Actions. [Whichcote: sermon in "The Cambridge Platonists" ed Campagnac]

Episteme

and Doxa.

Episteme

and Doxa.

The ethical problem

facing the typical human being is two-fold. First, there is a temptation

to ignore the dictates of reason; and second, one never has certain

and clear knowledge ("episteme", in Greek) of what is good. The

first part of the problem can be treated as an aspect of the latter; for

if one

knew clearly that some conclusion was reasonable and that

no other was possible, then one would not be "tempted to ignore the dictate

of reason". One might earnestly wish that some other conclusion was possible,

but given that one knew clearly that it wasn't; one would necessarily

have

to accept, no matter how reticently, that "A is A" and make the best of

it! Of course, the best kind of knowledge that anyone can ever have of

anything is confused at least by one's one subjective assumptions and prejudices.

This

kind of knowledge is called "doxa" in Greek and "belief" in English.

Sometimes, one's belief can, with some good accuracy, correspond to objective

reality. In such a case, the belief is "true", and the Greek adjective

"ortho-dox" is appropriate.

Disinformation of the Will.

The Platonic account of internal moral conflict is then framed in terms of "wishful thinking". Whereas the most plausible view of a question might be "such and such", there are always alternative possibilities which simply cannot be excluded, given the partial and ambiguous nature of human knowledge. It is always open to the moral agent to choose to ignore the most plausible conclusion as to what is good and so the prudent course of action, in favour of some other conclusion that is preferable, according to some (perhaps in itself reasonable, noble and proper) metric. So, a husband faced by a midwife with the medical dilemma "save the mother or save the unborn child" might personally desire one objective above the other and so be motivated to favour this conclusion whatever the dictates of reason told him was the proper action.Once one starts to favour conclusions because they are more attractive, convenient or pleasant, rather than because one believes they are right, then one has adopted a false metric for what is right. This is the Platonic version of concupiscence and can be seen to correspond to St Paul's testimony just as well as the Aristotelian version. In fact this disinformation of the will might be identified with "the sin living within me" referred to by the Apostle [Rom 7:20], as also the "law at war with the law of my mind .... the law of sin, which dwells in my members" [Rom 7:22] and "the flesh which serves the law of sin" [Rom 7:25]. On the other hand, the Apostle's language in earlier verses of his Epistle to the Romans is altogether more confused: "I do not do what I want to" [Rom 7:15] "nothing good dwells within me .... I can will what is right, but I cannot do it" [Rom 7:18]

Correcting Concupiscence.

The Platonic analysis has the distinct advantage of not referring to the undefined concept of "will-power". On this view, concupiscence is again a defect of the will, but no longer a mysterious weakness that is to be overcome by exercise. Rather, it is a disinformation to be overcome by education, meditation, encouragement and enlightenment. This is not to say that discipline does not have a valid role in the correction of concupiscence: an effective way for "wishful thinking" to be brought to brook is through confrontation with objective reality! In the end the person who spends money profligately will have to stop because they run out of funds: or they will take up a life of crime to finance their extravagance and, hopefully, they will be caught, prosecuted, convicted and punished. St Paul tells us that God disciplines those who He loves.Culpability.

The notion of "blame" or "culpability" can be identified with the objective fact of a disordered will. When a person systematically adopts a self-satisfied, complacent or conceited metric for what is right, then that metric is the proximate cause of whatever evil actions he or she perpetrates: their disordered will is "to blame", and it is appropriate for them to be punished so as "bring them to their senses", and to persuade them to adopt a more objective metric. Of course, issues such as "who is to say what is an evil act?" and "doesn't this just amount to brain-washing by the majority consensus in society?" arise here, but they lie outside the terms of reference of this essay. Also, the uses of punishment to exact retribution and to deter others as opposed to reforming the convict require consideration. It is far from clear that any "punishment can fit the crime" with regard to all three objectives simultaneously, except by some happy coincidence.Evil is sickness.

It follows from this view that personal evil is always a species of sickness. By one way or another, a person has gotten themselves into a position where they have an improper and, to a degree, settled view of what is right and wrong. Their wickedness is simply this disinformation of the will. It evolved out of natural predispositions, under the influence of external events and random mental processes, in other words by their "Free Will". It is not the fault of the person that "they are evil", it is just a fact about them. They were not "born bad". If their concupiscence can be rectified, then the fact that they used to be evil is no longer of any importance: it was no more their fault (for which they should carry guilt) that they were evil than it is their merit that they are no longer so. The fault lies in the past: in the evil will that they have lost. The virtue lies in the present: in the good will that they have gained. Hence the Judaeo-Christian view that repentance (which means the changing of an evil will into a good will) automatically calls for immediate and unqualified forgiveness.The Eternal Perspective.

The Aristotelian idea that the "will must be strengthened to resist temptation" is inconsistent with the idea that in the New Creation there will be no temptation: the obvious question "why bother to achieve this goal, which will be redundant in the infinite future?" has no possible answer. On the other hand, the idea that all ignorance, prejudice, wishful thinking and derogation from rationality should be expunged from human nature requires no justification beyond itself. In fact, it could be argued that this is a necessary (and even sufficient!) pre-condition for the New Creation to be a reality!If it feels good, it may well be good.

A major conclusion that follows from the Platonist analysis is that there is no need to say that everything that is attractive and desirable is sinful. The fact that one's will is disinformed does not mean that one should avoid all pleasure in favour of pain. As I have argued elsewhere, pleasure is the natural reward for choosing what is good. The fact that sometimes it can be unhealthily obtained by short-cuts (e.g. heroin, fornication, dishonesty, violence, betrayal of trust) does not mean that pleasure is in itself wrong or illicit. St John of the Cross reported (and had difficulty with the fact) that he experienced sexual arousal when in the deepest states of rapport with God. This was a sign of the ultimate desirability of God, and that the Saint's whole being, which included his body, was excited at the prospect of being caught up in the inner life of the Trinity.The Beatific Vision

It should be obvious that Episteme is unobtainable in this life. All mortal knowledge is necessarily filtered by the presumptions and working hypotheses, prejudices and expectations that on the one hand motivate, guide and enable, yet on the other hand limit and impoverish our interaction with and investigation of the world. No matter how objective we try to be - and this is a laudable aim, I strongly believe that there is something very definite "out there" quite independent of our perception of it - we cannot attain to pure knowledge and abbsolute truth. On one level this is regrettable: being a limitation of our state of being. On the other it is wonderful: because it makes Free Will possible. Only where there is uncertainty and subjectivity can there be room for opinion and judgement and discretion: in fact for the exercise of any of the virtues.God has no Free Will.

Of course, none of this is true of God. God cannot have Free Will, so far as his agency in the Universe is concerned. For God to be God, He must be omniscient and the only objective observer: being the first cause of all that is created. God has perfect Episteme of the whole Cosmos. God has no opinions or views or policies or positions. God has the facts, just as they are, with total clarity of vision. God has no need to be rational; all things are equally and immediately present and obvious to Him. Though He is very well aware of the inter-relatedness and inter-dependence of everything, God does not have to rely on His understanding of contingency and causality to deduce conclusions from premises. I repeat, God cannot have any Free Will: there is no possibility of variation or weakness or hesitation in God."Every good endowment and every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of Lights, in whom there is no variation or shadow of turning." [Jas 1:17]Moreover, it is plausible that the room for the exercise for human Free Will in the context of the Beatific Vision will be severely limited. Even if it is extravagant to presume that the saints (will) have an abiding episteme about everything, it would seem that the correct answer to any doubt or question will be immediately available "on demand". This will mean that there is no room for any divergent views "in Heaven", not because a party line is imposed from above; but just because the untainted and impartial truth is freely and abundantly available.

The need for subjectivity.

It is plausible that it is precisely in order to give us "the space" to make mistakes and so to learn and to grow that God places us in an environment that is not entirely friendly, with limited intellectual faculties and only subjective knowledge to live by. Free Will is not a value in itself: even if Neil Peart, the lyricist-drummer of the rock group RUSH, might at least once have thought otherwise! Free Will is only of value in attaining to Truth. It is a means of attaining to ortho-doxy; but by an internalization of The Law: not by an external and slavish obedience to external authority."And I will give them one heart, and put a new spirit within them; I will take the stony heart out of their flesh and give them a heart of flesh, that they may walk in my statutes and keep my ordinances and obey them; and they shall be my people, and I will be their God." [Ezk 11:19,20]This is what it means to become a Friend of God."But this is the covenant which I will make with the house of Israel after those days, says the Lord: I will put my law within them, and I will write it upon their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people. And no longer shall each man teach his neighbour and each his brother, saying, 'Know the Lord,' for they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, says the Lord; for I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more." [Jer 31:33,34]

Grace and Favour

The

Apostle tells us (in highly Platonic language) that God "desires

all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth" [I

Tim 2:4], yet Jesus seems to tell us that

"few"

are in fact saved [Matt

7:13,14]. These two statements seem to be contradictory. If

God is all-loving and all-powerful, how can He bear to allow so

many to stray from the way to "life" and instead

find their way to "destruction". This is a

sub-set of the more general (and very serious) "Problem

of Pain", on which C.S. Lewis for one has written. It seems that something

is wrong here, someone (most plausibly God) "at fault". There seems to

be a pressing need to come to God's defence. Before making whatever feeble

attempt I may, I think it important to consider what one might mean by

"salvation" and "destruction".

The

Apostle tells us (in highly Platonic language) that God "desires

all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth" [I

Tim 2:4], yet Jesus seems to tell us that

"few"

are in fact saved [Matt

7:13,14]. These two statements seem to be contradictory. If

God is all-loving and all-powerful, how can He bear to allow so

many to stray from the way to "life" and instead

find their way to "destruction". This is a

sub-set of the more general (and very serious) "Problem

of Pain", on which C.S. Lewis for one has written. It seems that something

is wrong here, someone (most plausibly God) "at fault". There seems to

be a pressing need to come to God's defence. Before making whatever feeble

attempt I may, I think it important to consider what one might mean by

"salvation" and "destruction".

What does it mean "to be saved"?

I suppose this to signify "being a friend of God at the last, so that one escapes Hell". I emphasize the negative only so as to avoid opening up even more unanswerable questions about the nature of Heaven, the Resurrection and the New Creation. My trite answer begs the questions:- Why does Hell exist at all?

- Why is it impossible to leave Hell, once one has chosen to enter?

- Why does the state of one's relationship with God at the moment of death

as opposed to some kind of average over one's life) matter.

So just Who are Saved, and Why and How?

As

I've already mentioned, there is a paradox here. God, who is all-powerful

and all-loving, desires everyone to be saved. To this end, God gives all

(wo)men "sufficient grace" to be saved. Yet not all are saved. Why? As

I understand it, there are three generic answers to this problem. The

controversy generated has generally been heated and given rise to extreme

degrees of ill will: simply because the issues involved are very delicate.

For myself, I well recall being sent into a serious three day depression

by a Priest of Opus Dei, who insensitively and almost gleefully argued

(as best I recall) that those who have not had the Gospel preached to them

explicitly have no chance of being saved!

As

I've already mentioned, there is a paradox here. God, who is all-powerful

and all-loving, desires everyone to be saved. To this end, God gives all

(wo)men "sufficient grace" to be saved. Yet not all are saved. Why? As

I understand it, there are three generic answers to this problem. The

controversy generated has generally been heated and given rise to extreme

degrees of ill will: simply because the issues involved are very delicate.

For myself, I well recall being sent into a serious three day depression

by a Priest of Opus Dei, who insensitively and almost gleefully argued

(as best I recall) that those who have not had the Gospel preached to them

explicitly have no chance of being saved!

What is grace?

Often grace is talked of as if it was a fluid that one went to a filling station (such as the sacraments, prayer or the scriptures) to replenish or tank-up on. This is arrant nonsense! The deepest and primary meaning of grace is Holy Spirit Herself, active in the will (or "heart") of the Friend of God. This is what is technically referred to as "Uncreated Grace". The second meaning is the immediate effects of this activity of Holy Spirit: the healing of the will and the insights; knowledge; wisdom and unexpected abilities that this gives rise to, this is "actual grace" or "graces". The root meaning of the word "grace" is "free": both in the sense that there is no charge for a thing and in the sense that it is liberating. Hence, God graciously graces us with His grace: God of His own initiative and looking for no recompense liberates us from our limitations by engaging with us and offering us His friendship. Grace is not an Aristotelian substance. It is a process; an engagement; an encounter with God. It is the helping hands offered by parents to their child who is learning to walk. It is the roar of approval from the crowd of supporters at the sports stadium or fans at the rock concert. It is the compassionate caress or smile of encouragement offered to the person who is suffering. It is the conversation of sharing between friends. It is the embrace of lovers.The Jesuit position.

The Jesuits have generally taken the most "liberal" position. Typically, they argue that some people are simply not saveable, given God's best efforts (short of coercion!) God is simply unable to bring them to repentance. Their Free Will is sovereign and the grace that should be sufficient to effect their conversion in fact fails to do so. It is not "efficient", even though it is super-abundant!The Calvinist and Jansenist position.

As best I understand it, Calvin believed that God positively intends that some people are not saveable. For some reason, Calvin thought that God wants to see Hell well stocked, and that He uses the Devil as His agent to induce those who are pre-destined to Eternal Punishment to sin, and so to deserve this fate! This view certainly ensures that God's "sovereign power" is maintained, but at the expense of (it seems to me) a denial of the central tenet of Christianity: "God is Love".The Dominican position.

The Dominicans have tried to adopt an intermediate position. In this view, God chooses to put in enough effort to save those whom He chooses. While all are potentially saveable, not all are actually saved. God gives "sufficient" grace to all, but only "efficient" grace to a subset: "the many". Again, God's "sovereign power" is apparently maintained, because God chooses who will be saved and who will be damned. Nevertheless, He neither wants anyone to be damned [II Tim 2:4], nor works to advance such a purpose.The Reality of Choice.

Perhaps there are choices to be made. Perhaps either A or B can be saved, but not both; the possible histories available to these two individuals at the Creation are inter-twined and in conflict. The initiative as to which is saved and which damned is then with God: an unenviable choice. Although God is almighty, He is not able to make choices that are internally at odds with themselves. God cannot choose an absurdity or a nonsense. Reality has to be internally coherent. We can only trust that God will do what is best, on some reasonable and loving account of the matter: that God must have made "the best of all possible worlds", even though at times this seems highly implausible.God causes everything, but determines nothing.

This is not convincing, for one over-riding reason. The Church definitely teaches that God specially creates each human soul as a singular act of divine power. It would therefore seem that God has good access to at least the initial conditions of each human life, and so is in a position to pre-determine its outcome. Surely, God should be able to use this control to ensure (without ever using coercion) that (whatever happens in its life history) each soul escapes perdition. However, we have already seen that in the case of even the simplest of non-linear systems, approximate control of initial conditions is not enough to ensure that a particular outcome is achieved. Just as the slightest deviation in the starting point of the pendulum bob corresponds to any number of switches from "North" to "South" as its final resting place, so it may be that God can only cause in the weak sense (that excludes the notion of determine) the salvation or damnation of individual souls. Given the complexities of the Cosmos, no matter how God tweaks the variables at His disposal, perhaps certain undesirable outcomes cannot be avoided.Is God reckless?

Still, it does seem that God is Reckless. Why does He make a Cosmos in which so many people suffer, and in which any at all end up in Hell? Wouldn't it have been better that none were made, rather than that many suffer eternally? One is tempted to suggest that "perhaps God couldn't help himself!" He got carried away with enthusiasm for Being Himself, and with making more being! The Cosmos was something of a mistake: God didn't understand what suffering was (being incapable of it Himself) and only after the event "realized what He'd done" and is now trying to make the best of a bad job. Of course, this is all quite heterodox, and moreover makes very little sense. Given that God is outside time, even if He could have made a mistake, He couldn't "later" realize His error. This whole picture (though, for me, emotionally attractive) is metaphysical nonsense.Further thoughts on this topic will be found elsewhere.