Return to Theological Thoughts.

"the Jansenists did not hold to the heresy of 'Jansenism' as we now 'know it'. Their doctrine on grace would appear to be within the limits of what the Church has permitted to other groups, such as the Thomists and the Augustinians."

Luis de Molina .... maintained that efficacious grace does not move the free will to cooperate with it but that the free will makes grace efficacious by co-operating with it. The Molinists emphasized an universal divine salvific Will and often maintained that God elects to salvation those whom He foreknows will cooperate with his grace. Thus God's foreknowledge, the scientia media, was held to act as a sort of “middle” mechanism between the human free will on the one hand, and the efficacy of grace and of divine election on the other. The doctrine caused a massive theological row between the Thomist Dominicans and the Molinist Jesuits..... Those opposed to the doctrine termed it “Semi-Pelagianism” because it was considered to have important features in common with the heretical doctrine of the fifth century monk Pelagius, against which St. Augustine had fought.Contrary to the proposition that Jansenius was orthodox, the Catholic Encyclopedia (quoted in blue) contends that:The .... Jesuits were the main partisans of Molinism..... They sought to remake Catholicism in a form which was more appealing to men..... They wanted to do away with hard doctrines.... They developed a laxist system of confessions, supposedly to make absolution easy, which was eventually condemned by Rome.... They argued that salvation was within the reach of all and that no extraordinary exertions were required. All had “sufficient grace” and but needed to cooperate with it to be saved. And man was held to be still capable of “naturally good” works, regardless of the Fall. The Jesuits admired the supposed virtues of the ancient pagans and assisted in the revival of neo-pagan “humanism” through their partial domination of the education of the influential.

Bishop Jansenius had listed over fifty errors of Louis de Molina in his "Augustinus".

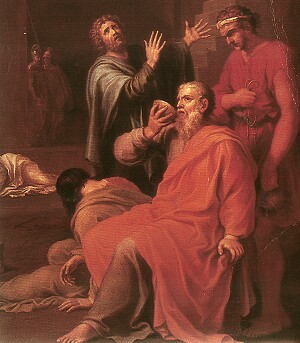

[Thomas Sparks]

"Already, in 1619, 1620, and 1621, his correspondence .... spoke of coming disputes for which there was need to prepare; of a doctrine of St. Augustine discovered by him, but little known among the learned, and which in time would astonish everybody, of opinions on grace and predestination which he dared not then reveal "lest like so many others I be tripped up by Rome before everything is ripe and seasonable."

The orthodox

doctrine is that original sin is nothing more than

the loss of supernatural

grace, the friendship

that the first human beings had with God. In our

present ethical state: characterized by imperfect knowledge of what is

just; coupled with moral responsibility and independence of will, we are

often induced to act unjustly by the short term advantages or pleasure

perceived to result from sin. This "concupiscence"

is not identical with original sin. Neither does it represent any loss

of integrity of human nature, which is not

corrupted or depraved at all. It simply reveals the condition of finite

beings left to fend for themselves in the world, without the continual

support of God. The dilemma of such beings is that they appreciate that

certain things are good for them and that others bad: but are uncertain

as to which are which. As knowledge of what is good (justice) grows in

the soul, by the action of God's grace: so the

attraction of sin dies away and the possibility of the exercise of

Free Will declines, until the Beatific

Vision is achieved.

The orthodox

doctrine is that original sin is nothing more than

the loss of supernatural

grace, the friendship

that the first human beings had with God. In our

present ethical state: characterized by imperfect knowledge of what is

just; coupled with moral responsibility and independence of will, we are

often induced to act unjustly by the short term advantages or pleasure

perceived to result from sin. This "concupiscence"

is not identical with original sin. Neither does it represent any loss

of integrity of human nature, which is not

corrupted or depraved at all. It simply reveals the condition of finite

beings left to fend for themselves in the world, without the continual

support of God. The dilemma of such beings is that they appreciate that

certain things are good for them and that others bad: but are uncertain

as to which are which. As knowledge of what is good (justice) grows in

the soul, by the action of God's grace: so the

attraction of sin dies away and the possibility of the exercise of

Free Will declines, until the Beatific

Vision is achieved.

In practice, Calvinism and its fellow travellers is characterized by attitudes exactly opposed to such a happy-go-lucky outlook. The reason for this is the following. It is psychologically very important to the proponent of such a doctrine of grace that they are personally one of the Elect: not a Reprobate travelling the Highway to Hell. Unfortunately, they can do nothing, according to their hypothesis, to effect this: all is at the whim of God. Nevertheless, if they happen to show obvious behavioural signs of being "godly" then they can hope to belong to the Elect. Hence, they set out to be "godly" in order to prove to themselves that "they have godliness in them", and so must be Heaven Bound. Of course, the manifestations of "godliness" typical of such misguided folk are not at all godly: dour legalism, prudery and sanctimoniousness. The playwright Ibsen's masterpiece "Ghosts" is in part a critique of such attitudes.

There was no general doctrinal unanimity amongst the Jansenists. They were united only in opposing what they saw as "Jesuitical tendencies". They had succeeded in having some Jesuits and their works condemned. The Jesuits and their sympathizers were angered by this attack. They set out to destroy the reputation of Jansenius and that of his followers at the Convent of Port Royal in France. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, in 1649 Cornet, a syndic of the Sorbonne .... extracted five propositions from the "Augustinus":

In 1650, eighty-five bishops wrote .... to Innocent X, transmitting to him the five propositions [and asking for him to rule on their orthodoxy]. The propositions were rejected as heretical in the Bull "Cum occasione" (31 May, 1653), the first four absolutely the fifth if understood in the sense that Christ died only for the predestined.

".... In my last letter I succeeded in showing that you accuse them of one heresy after another, without being able to stand by one of the charges for any length of time; so that all that remained for you was to fix on their refusal to condemn “the sense of Jansenius,” which you insist on their doing without explanation .... you have attempted to fortify your position by decrees, which .... gave no sort of explanation of the sense of Jansenius, said to have been condemned in the five propositions .... Had you mutually agreed as to the genuine sense of Jansenius .... the decisions which might pronounce it to be heretical would have touched the real question in dispute. But the great dispute being about the sense of Jansenius .... It is clear that a constitution which .... only condemns in general and without explanation the sense of Jansenius, leaves the point in dispute quite undecided."It became clear that the Jesuits were accusing the followers of Jansen of being crypto Calvinists. Everyone was agreed that Calvinism was heretical, because Trent had anathematized it.

[Blaise Pascal]

".... 'It is not sufficient', say you, 'for the vindication of Jansenius, to allege that he merely holds the doctrine of efficacious grace, for that may be held in two ways – the one heretical, according to Calvin, which consists in maintaining that the will, when under the influence of grace, has not the power of resisting it; the other orthodox, according to the Thomists and the Sorbonists, which is founded on the principles established by the councils, and which is, that efficacious grace of itself governs the will in such a way that it still has the power of resisting it.'The controversy went down hill from there: the convent of Port Royal was demolished and the nuns scattered. The Jansenists remained influential though, in France, and in Ireland too as Irish priests were trained in France. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:

.... All this we grant, father .... It is enough for my purpose .... that you now inform me that by the sense of Jansenius you have all along understood nothing more than the sense of Calvin .... we were all ready .... to join with you in condemning that error." [Blaise Pascal]

"[Eventually, the main part of the Jansenist party] abandoning the plainly heretical sense of the five propositions, and repudiating any intention to resist legitimate authority .... confined themselves to denying the infallibility of the Church with regard to dogmatic facts. Then, too, they were still the fanatical preachers of a discouraging rigorism .... and, under pretext of combating abuses, openly antagonized .... the legitimate part which heart and feeling play in its worship. With all their skilful extenuations they bore the mark of the levelling, innovating, and arid spirit of Calvinism."

[The followers of Jansenius acknowledge that] .... an effective resistance may be made to those feebler graces which go under the name of exciting or inefficacious, from their not terminating in the good with which they inspire us .... they are, moreover, as firm in maintaining, in opposition to Calvin, the power which the will has to resist even efficacious and victorious grace, as they are in contending against [the Jesuit theologian] Molina for the power of this grace over the will, and fully as jealous for the one of these truths as they are for the other.

This

is the exact point at issue. First, Pascal equates the status of Molinism

with that of heterodox Calvinism. Second, he confuses the ability

of God to force the will, with the unwillingness of God to do any

such thing. The fact that God, being almighty, has the power to intellectually

and spiritually rape His creation does not mean that He, being

kind, has the slightest inclination to do so!

This

is the exact point at issue. First, Pascal equates the status of Molinism

with that of heterodox Calvinism. Second, he confuses the ability

of God to force the will, with the unwillingness of God to do any

such thing. The fact that God, being almighty, has the power to intellectually

and spiritually rape His creation does not mean that He, being

kind, has the slightest inclination to do so!

They know too well that man, of his own nature, has always the power of sinning and of resisting grace;This is because of Free Will, based on a degree of moral ignorance.

and that, since he became corrupt, he unhappily carries in his breast a fount of concupiscence which infinitely augments that power;This is heterodox, as explained above.

but that, notwithstanding this, when it pleases God to visit him with His mercy, He makes the soul do what He wills, and in the manner He wills it to be done, while, at the same time, the infallibility of the divine operation does not in any way destroy the natural liberty of man, in consequence of the secret and wonderful ways by which God operates this change.Here Pascal makes the situation clear, for he says that God "makes the soul do what He wills, and in the manner He wills it to be done". Moreover, Pascal sees the only role of the human will as being the cause of sin, and sees its "power" in this regard being "infinitely augmented" by "concupiscence". While it is true that the only outcome that the exercise of Free Will is ever fully responsible for is sin, to dwell on this is to miss the point of Free Will.

It is by the exercise of Free Will that we learn what is good and just, by a process of trial and error. We learn this for ourselves as independent ethical agents, rather than simply adopting a prescriptive programme from Our Creator. At the end of the process, we can say openly and honestly to God that - entirely thanks to His patience, forbearance and help - we have come to understand what is good and why it is so for ourselves. We can say that we agree with and approve of it: and so chose it. This is far removed from a mere acceptance or willingness to conform to certain norms, on the say-so of authority. As St Thomas teaches, friendship is a relationship between persons who are not entirely unequal. If God's creatures are to become not just His "children": a relationship characterized by uncritical trust; but pass beyond this to become His friends: a relationship characterized by understanding and dialogue, then an independence of view and experience is absolutely necessary.

This has been most admirably explained by St. Augustine [who taught that] God transforms the heart of man .... inducing him to feel, on the one hand, his own mortality and nothingness, and to discover, on the other hand, the majesty and eternity of God, makes him conceive a distaste for the pleasures of sin which interpose between him and incorruptible happiness. Finding his chiefest joy in the God who charms him, his soul is drawn towards Him infallibly, but of its own accord, by a motion perfectly free, spontaneous, love - impelled; so that it would be its torment and punishment to be separated from Him.

Not but that the person has always the power of forsaking his God, and that he may not actually forsake Him, provided he choose to do it. But how could he choose such a course, seeing that the will always inclines to that which is most agreeable to it, and that, in the case we now suppose, nothing can be more agreeable than the possession of that one good, which comprises in itself all other good things? “Quod enim (says St. Augustine) amplius nos delectat, secundum operemur necesse est – Our actions are necessarily determined by that which affords us the greatest pleasure.”

This

is a very interesting passage. It is highly Platonist

in character, Augustine

being a great Christian proponent of the heritage of Socrates. As a Platonist,

I acknowledge that if a rational being clearly knows (has episteme

of) what is the case, then (s)he can do nothing other than chose to do

what is right. There is no possible motive for them doing otherwise.

"Quod

enim amplius nos delectat, secundum operemur necesse est." St Augustine's

use of the word "delectat" is a little unfortunate, however. He seems thereby

to equate subjective pleasure

with objective good. Although subjective pleasure

generally indicates objective good, this is not inevitable: take the counter

example of the use of the drug heroin. The rational being is motivated

by episteme, not by delectation: with the proviso that the wise find

their greatest pleasure in truth.

This

is a very interesting passage. It is highly Platonist

in character, Augustine

being a great Christian proponent of the heritage of Socrates. As a Platonist,

I acknowledge that if a rational being clearly knows (has episteme

of) what is the case, then (s)he can do nothing other than chose to do

what is right. There is no possible motive for them doing otherwise.

"Quod

enim amplius nos delectat, secundum operemur necesse est." St Augustine's

use of the word "delectat" is a little unfortunate, however. He seems thereby

to equate subjective pleasure

with objective good. Although subjective pleasure

generally indicates objective good, this is not inevitable: take the counter

example of the use of the drug heroin. The rational being is motivated

by episteme, not by delectation: with the proviso that the wise find

their greatest pleasure in truth.

However, God's grace does not work by giving episteme. The best that the justified can hope for in this life is ortho-doxy, coupled with "sanctifying grace": the indwelling of charity which is the substantial Love that is God HimSelves. This is an intuition of the heart rather than an episteme of the mind. The latter is reserved until the Beatific Vision is attained: at which point Free-Will necessarily ceases.

The verbs that Pascal here says that Augustine attributes to God are all unfortunate. "Inducing", "makes", "charms" and "drawn" are all deterministic, even mechanistic or magical in connotation.

Moreover, it is not the experience of the saints (in particular, the Apostle Paul) that sin ceases to have any allure. Even Our Lord was tempted by Satan. Moreover, the Church has condemned the idea that those who are at any time justified are thereby certainly saved. She rather commends the practice of praying for the grace of final perseverance: which practice is contrary to Pascal's doctrine.

Moreover, if Pascal's doctrine were to be true, how could the fall of Lucifer be explained? Why should not have God granted to the greatest Angel infallibly efficient grace?

The truth of the matter is as follows:

.... it follows that we act of ourselves, and thus .... that we have merits which are truly and properly ours; and yet, as God is the first principle of our actions .... “our merits are the gifts of God,” as the Council of Trent says.This is a playing with words. Of course God enables us to do whatever it is that we do in advance of our sanctification. However, enabling is not at all the same thing as coercing. God enables by offering us His friendship: by cajoling, encouraging, persuading and seducing.By means of this distinction we demolish the profane sentiment of Luther, condemned by that Council, namely, that “we cooperate in no way whatever towards our salvation any more than inanimate things”; and, by the same mode of reasoning, we overthrow the equally profane sentiment of the school of Molina, who will not allow that it is by the strength of divine grace that we are enabled to cooperate with it in the work of our salvation, and who thereby comes into hostile collision with that principle of faith established by St. Paul: “That it is God who worketh in us both to will and to do”.

.... in this way we reconcile all those passages of Scripture .... such as the following: “Turn ye unto God” – “Turn thou us, and we shall be turned” – “Cast away iniquity from you” – “It is God who taketh away iniquity from His people” – “Bring forth works meet for repentance” – “Lord, thou hast wrought all our works in us” – “Make ye a new heart and a new spirit” – “A new spirit will I give you, and a new heart will I create within you”.This all turns on the exact meaning of the word "making". I am no great fan of St Augustine's theology of grace, and have no particular wish to defend his every teaching. Nevertheless, his juxtaposition of "enables" with "making" signals a subtlety and tension in his thought that is altogether lacking in Pascal's stark presentation. In one sense, God is inevitably the cause of everything that we do. In this sense He "makes" us do everything that we do. To a degree, He is the "cause of evil": but only in that He chooses not to frustrate our ill-will by opposing to it His almighty power: but rather continues to ratify and establish our own will independent of His own. No reality comes to pass unless God wills it, and so no evil arises unless God permits it.The only way of reconciling these apparent contrarieties, which ascribe our good actions at one time to God and at another time to ourselves, is to keep in view the distinction, as stated by St. Augustine, that “our actions are ours in respect of the free will which produces them; but that they are also of God, in respect of His grace which enables our free will to produce them”; and that, as the same writer elsewhere remarks, “God enables us to do what is pleasing in his sight, by making us will to do even what we might have been unwilling to do.”

.... the Thomists hold .... both the power of resisting grace, and the infallibility of the effect of grace; of which latter doctrine they profess themselves the most strenuous advocates, if we may judge from a common maxim of their theology .... “When efficacious grace moves the free will, it infallibly consents; because the effect of grace is such, that, although the will has the power of withholding its consent, it nevertheless consents in effect.”This is not to say a great deal. It amounts to the truism that when the will does consent to the influence of grace, then the grace is said to be efficacious. Hence, if one is told that grace is in some case efficacious then one knows necessarily and infallibly that the free will consented to it!

[St Thomas teaches that:] “The will of God cannot fail to be accomplished; and, accordingly, when it is His pleasure that a man should consent to the influence of grace, he consents infallibly, and even necessarily, not by an absolute necessity, but by a necessity of infallibility.”This is again inevitable, and not to the point. For the Divine Pleasure is of certain foreknowledge, not of coercion.

Antecedently, God wills that harvests come to maturity. Nevertheless, He allows some harvests to fail. Similarly, He wills in principle the salvation of all men, though for some higher good, of which He alone is judge, it seems that He permits some sinners to die unrepentant and so be damned. Nevertheless, He gives grace to each, sufficient that all should be saved: much more than "justice" could possibly require.

A Thomist would object to this, arguing that this amounts to "a good" (a saving action), which does not entirely come from God, who is the source of all good. If, with equal grace, and amid equal circumstances, one sinner is converted and the other not, then the convert has a good which he has not directly received from God, but it would seem randomly.

The Molinist would agree with the principle that all good comes from God. He would seek to establish this here by asserting that God, foreseeing that placing Peter in some situation would result in him being converted, consequently wills to bring those favourable circumstances into being, rather than others in which he would be lost.

The Thomist would object that this explanation reduces the absolute principle of intrinsic efficacy of grace to a relative principle of extrinsic efficacy only. The Molinist makes grace efficacious, not of itself and intrinsically, but only by circumstances which are extrinsic to the action of grace proper.

The Molinist would deny this, replying that the consequent willing of circumstances is part and parcel of the Divine Act of grace that is efficacious: so the efficacy of grace is intrinsic, not extrinsic.

The Molinist would counter attack by demanding how, if self-efficacious grace is necessary to do good, how can it be said that sufficient grace truly gives a real power to act? It would seem that the main and absurd characteristic of such a real power to act is that it never ever produces any action!

It does so, the Thomist would reply, because the real power to act

is easily distinguished from the act itself. All that God wills can come

to pass without our freedom being forced, because God gently seduces that

freedom without destroying it. If the sinner does not resist sufficient

grace, he will undoubtedly receive efficacious grace. God wills efficaciously

that we freely consent and we do freely consent. While the will always

has the real power to resist grace, actual resistance is something else.

In the case of efficient grace, God simply perseveres until the will's

free resistance is overcome, and the sinner is finally persuaded to do

what is right.

The

Molinist would reply that the Thomist has now acceded his point. The granting

of efficient grace has now being made contingent on a sinner not resisting

sufficient grace! The only point at issue is why in some cases God seems

to persevere and in others He seems not to. If God knew from all eternity

that Judas would not profit by the sufficient

grace that was in fact accorded to him, why did God not give to Judas,

those additional graces to which He knew that Judas would respond?

The

Molinist would reply that the Thomist has now acceded his point. The granting

of efficient grace has now being made contingent on a sinner not resisting

sufficient grace! The only point at issue is why in some cases God seems

to persevere and in others He seems not to. If God knew from all eternity

that Judas would not profit by the sufficient

grace that was in fact accorded to him, why did God not give to Judas,

those additional graces to which He knew that Judas would respond?

The Thomist would respond by asserting the principle: "all good results from God's efficacious will and all evil arises with God's permission". Hence God permitted the final impenitence of Judas. Had God not permitted it, it would not have come to pass. If God had not considered permitting it, He could not have foreseen that it would occur. Now, God would not have permitted it, had He willed efficaciously to save Judas. For reasons unknowable to us, it would seem that God did not so will. It should be remembered that God did not owe it to Judas in simple justice that he should escape damnation.

"Faith, then, as well in its beginning as in its completion, is God’s gift; and let no one have any doubt whatever, unless he desires to resist the plainest sacred writings, that this gift is given to some, while to some it is not given. But why it is not given to all ought not to disturb the believer, who believes that from one all have gone into a condemnation, which undoubtedly is most righteous; so that even if none were delivered therefrom, there would be no just cause for finding fault with God." [St Augustine of Hippo: "Predestination of the Saints" Ch 16]The Thomist would counter-attack by demanding to know if there is in God's foreknowledge any passivity: a dependency on the course of events? Is God's knowledge causal and determining, as befits the Uncaused First Cause, or itself contingent on merely cosmic events?

Sacred Scripture uses the term predestination [Rom 8:29-30, Eph 1:5,11], but what is meant by the term is unclear.

"If any one saith, that all works done before Justification, in whatsoever way they be done, are truly sins, or merit the hatred of God; or that the more earnestly one strives to dispose himself for grace, the more grievously he sins: let him be anathema."James Akin comments:

[Oecumenical Synod of Trent: session VI: canon 7]"If any one saith, that, in every good work, the just sins venially at least, or - which is more intolerable still - mortally, and consequently deserves eternal punishments; and that for this cause only he is not damned, that God does not impute those works unto damnation; let him be anathema."

[Oecumenical Synod of Trent: session VI: canon 25]

What would a Catholic think of this teaching? While he would not use the term "total depravity" to describe the doctrine, he would actually agree with it. The accepted Catholic teaching is that, because of the fall of Adam, man cannot do anything out of supernatural love unless God gives him special grace to do so. Thomas Aquinas teaches that special grace is necessary for man to do any supernaturally good act, to love God, to fulfil God's commandments, to gain eternal life, to prepare for salvation, to rise from sin, to avoid sin, and to persevere.

"For every salutary act internal supernatural grace of God (gratia elevans) is absolutely necessary"I reply that all this is quite obvious in fact and quite misleading in tone. For a (wo)man to do anything that is worthwhile in forwarding his/her relationship with God, it is first of all necessary that (s)he has such a relationship with God. One cannot earn God's friendship: Pelagianism. One cannot even do something that might incline God towards offering His friendship: Semipelagianism. Sinners are not, of themselves, attractive to God. He has nothing to gain from any association with one of them. When God offers friendship to sinners it is always unmerited and absolutely gracious. Moreover, the offer of friendship is always at God's initiative and on His terms. Fallen, finite and sinful (wo)man is in no position to make the first move!

[Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma: Dr Ludwig Ott IV.I.8]"as often as we do good God operates in us and with us, so that we may operate"

[Second Council of Orange, canon 9]"man does no good except that which God brings about"

[Second Council of Orange, canon 20]."Whoever says that without the predisposing inspiration of the Holy Ghost and without his help, man can believe, hope, love, or be repentant as he ought, so that the grace of justification my be bestowed upon him, let him be anathema" [Oecumenical Synod of Trent: session VI: canon 3]

The

doctrine of unconditional election means God does not base His choice of

individuals on anything other than His own good will. God chooses

whomsoever He pleases and passes over the rest. The ones God chooses

will desire to come to Him, will accept His offer of salvation, and will

do so precisely because He has chosen them.

The

doctrine of unconditional election means God does not base His choice of

individuals on anything other than His own good will. God chooses

whomsoever He pleases and passes over the rest. The ones God chooses

will desire to come to Him, will accept His offer of salvation, and will

do so precisely because He has chosen them.

"[The Lord] says to Moses, 'I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion.' So it depends not upon man's will or exertion, but upon God's mercy .... So then he has mercy upon whomever he wills, and he hardens the heart of whomever he wills." [Rm. 9:15-18]James Akin comments:"God wills to manifest his goodness in men: in respect to those whom he predestines, by means of his mercy, in sparing them; and in respect of others, whom he reprobates, by means of his justice, in punishing them .... Yet why he chooses some for glory and reprobates others has no reason except the divine will. Hence Augustine says, 'Why he draws one, and another he draws not, seek not to judge, if thou dost not wish to err.'"

[Summa Theologica I:23:5, citing Augustine, Homilies on the Gospel of John 26:2.]

What would a Catholic say about this? He certainly is free to disagree with the Calvinist interpretation, but he also is free to agree. All Thomists and even some Molinists (such as Robert Bellarmine and Francisco Suarez) taught unconditional election.I reply, that at one level, this doctrine is inevitable. God's offer of friendship to a sinner is unmerited. It cannot be elicited. On the other hand, it is fairly clear that the Tradition has it that God offers everyone His friendship. While in some logical sense God could be choosy about who He invites to be His friends, in fact God is indiscriminate. Jesus socialized with the dregs of society: whores and fraudsters. St Augustine is right to warn against attempting to understand why God's invitation to some is effective and to others ineffective. It might seem that "if only God persisted, the reprobate might be won over", but perhaps this is not the case.

On another level, this doctrine is reprehensible. It can be taken to

mean that God chooses not to go the extra mile with some people:

as if he decided beforehand that some were simply not worth bothering with.

An extreme version of this interpretation is "double predestination",

a heretical doctrine constitutive of Calvinism. This claims that, in addition

to positively electing some people to salvation, God also purposefully

and deliberately causes others to be damned.

The less extreme version is "passive reprobation", a doctrine characteristic

of Thomism. This claims that while God positively predestines some people

to salvation by lavishing on them infallibly self-efficient grace, He simply

passes

over the remainder: granting them only "sufficient" grace that inevitably

turns out to be ineffective. They do not come to God, but it is because

of their sin, not because God positively damns them.

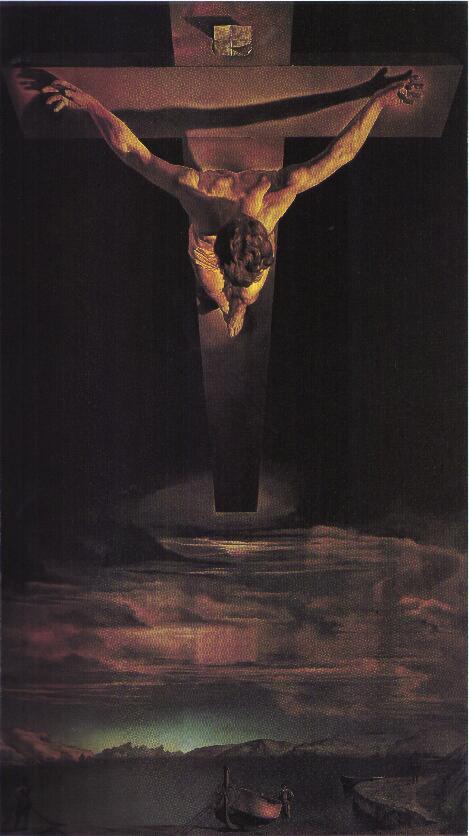

Calvinists

believe the atonement is limited: that Christ offered it for some men but

not for all. They claim Christ died only for the elect. They attempt to

prove this by citing Scriptural texts which say that Christ died for his

sheep, for his friends, and for the Church. Now, a person may be said to

have given himself for one person or group without denying that he gave

himself for others as well. Hence, these statements do not prove that Christ

did not also give himself for all men. Sacred Scripture explicitly states

that Christ is "the Saviour of the world," [Jn

4:42] and "the propitiation for our sins,

and not for ours only but also for the whole world"

[1Jn 2:2]. These passages, as also the teaching of the Church [Ott

III.2.10] make it clear that Christ died to atone for all (wo)men.

Above all, it must be remembered that God "desires

all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth"

[1Tim 2:4], see also Ezekiel 33:11.

Calvinists

believe the atonement is limited: that Christ offered it for some men but

not for all. They claim Christ died only for the elect. They attempt to

prove this by citing Scriptural texts which say that Christ died for his

sheep, for his friends, and for the Church. Now, a person may be said to

have given himself for one person or group without denying that he gave

himself for others as well. Hence, these statements do not prove that Christ

did not also give himself for all men. Sacred Scripture explicitly states

that Christ is "the Saviour of the world," [Jn

4:42] and "the propitiation for our sins,

and not for ours only but also for the whole world"

[1Jn 2:2]. These passages, as also the teaching of the Church [Ott

III.2.10] make it clear that Christ died to atone for all (wo)men.

Above all, it must be remembered that God "desires

all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth"

[1Tim 2:4], see also Ezekiel 33:11.

This is not to say there is no sense in which limitation may be ascribed to the atonement. In going to the cross, Christ intended to make salvation possible for all, but it is not at all clear that he intended to make salvation actual for all. While the grace merited by the atonement is sufficient to expiate the sins of all men, it does not seem that this grace is effective in the case of everyone. While it is possible that Hell is empty: at least of human souls, I am not sanguine that this is the case. Although the objective sufficiency of the atonement is certainly not limited: its subjective efficiency is apparently limited. The difference between the atonement's sufficiency and its efficiency explains the Apostle Paul's statement that God is "the Saviour of all men, especially those who believe." [1Tim 4:10].

James Akin asserts that:

"While a Catholic could not say that the atonement was limited in that it was made only for the elect, he could say that the atonement was limited in that God only intended it to be efficacious for the elect (although he intended it to be sufficient for all)."It seems to me that this is either a truism not worth stating (and hence the fact that it is stated makes me suspicious of what lies behind it) or entirely false. Interpreted as a truism, it states that the atonement was intended to be efficacious only for those it was efficacious for. Interpreted otherwise: furthering the capricious image of God lurking in the Thomist doctrine of "passive reprobation", it suggests that the Holy Trinity restricted the character of the atonement in some manner so that in point of fact only certain souls would benefit from it. This amounts to "double predestination", brought in by the back-door. I argue elsewhere that the Thomist position is well down a slippery slope towards Calvinism: which at least has the arid attraction of logical consistency!

Calvinists

believe that when God gives a person the grace that enables him to come

to salvation, the person always responds and never rejects this grace,

this is the doctrine of irresistible grace. This makes it sound as though

God forces people against their will to come to him. This doctrine is contrary

to Scripture, which gives clear indication that grace can be resisted.

Stephen Protomartyr tells the Sanhedrin, "You always

resist the Holy Spirit!" [Acts 7:51].

For this reason some Calvinists prefer the term "efficacious grace." According

to Blaise Pascal, this idea: that God's enabling grace is intrinsically

efficacious so that it always produces salvation is common

territory with Jansenists and Thomists.

Calvinists

believe that when God gives a person the grace that enables him to come

to salvation, the person always responds and never rejects this grace,

this is the doctrine of irresistible grace. This makes it sound as though

God forces people against their will to come to him. This doctrine is contrary

to Scripture, which gives clear indication that grace can be resisted.

Stephen Protomartyr tells the Sanhedrin, "You always

resist the Holy Spirit!" [Acts 7:51].

For this reason some Calvinists prefer the term "efficacious grace." According

to Blaise Pascal, this idea: that God's enabling grace is intrinsically

efficacious so that it always produces salvation is common

territory with Jansenists and Thomists.

James Akin asserts that:

A Catholic can agree with the idea that enabling grace is intrinsically efficacious and, consequently, that all who receive this grace will repent and come to God.I reply that justifying grace is intrinsically efficacious in the sense that whenever God sees that He can seduce a soul then He certainly chooses to do so, and this action is infallible: because it is based upon God's understanding of that soul's condition and propensities. Nevertheless, to insinuate that God does not do all that He could do to save some souls from eternal damnation is, in my judgement, abhorrent.

James Akin becomes becomes quite exercised about this doctrine, which in my mind is the silliest and least important of the five TULIP heresies. He asserts that:

If one defines "saint" as one who will have his sanctification completed, a Catholic can say he believes in a "perseverance of the saints" (all and only the people predestined to be saints will persevere).I reply that Catholic doctrine affirms that there are people who become friends of God for a while: are justified, and yet do not persevere. Others receive the gift of final perseverance. According to St Thomas, this is

".... the abiding in good to the end of life. In order to have this perseverance man .... needs the divine assistance guiding and guarding him against the attacks of the passions ..... [A]fter anyone has been justified by grace, he still needs to beseech God for the aforesaid gift of perseverance, that he may be kept from evil till the end of life. For to many grace is given to whom perseverance in grace is not give." [Summa Theologica I-II:109:10]The grace of final perseverance is, however, no more a magical divine fiat than efficacious grace, of which it is the asymptote. It is the continuing divine assistance and encouragement offered to all of God's friends. It is given and received when the justified soul continues, by God's grace to correspond to God's grace. It is offered and rebutted when, for some reason, the justified soul falls from grace and somehow and suddenly becomes so entangled in sin that it fails to repent and turns away from its Divine Lover, contrary to all His beseeching. Hence Christians pray "Lead us not into temptation".

The only sense in which a Catholic could affirm a version of this Calvinist

doctrine is in the specious form that "those who achieve sanctification"

certainly persevere until they have done so.