Navigate

History of Terry, later Mamook

Astoria Marine Construction Company

The Astoria Marine Construction Company, where CROD boats were built in the '30s and '40s, later became the major contributor to the war effort during WWII and the Korean Conflict.

If ever a time machine were built, it could never have a more successful voyage than a stroll through the Astoria Marine Construction Company. Here, machines that date from 1911 or 1930 or 1950 are operated by men with more than a half-century of experience as shipwrights.

Massive band saws, planers and rib-bending equipment attest to the company's heyday in the '40s and '50s, when it became the first yard in the country to build MSO's. The 165-foot minesweepers were built on contract from the Navy. At its peak the yard employed over 400 people.

(Ed. Note: The following narrative is a rich, detail-filled chronology of Joe Dyer's shipbuilding career, written by his son Tom. This text is excerpted with permission from Tom's manuscript.)

Now THAT'S a band saw

Introduction

Initially, the story of Astoria Marine Construction Company is the story of Joe Dyer and his early ventures with the Mansker brothers, Acme (Ac) and Clair. (see the Dyer Legacy section for more information.)

Astoria Shipbuilding

Joe Dyer’s first

shipyard, the predecessor to Astoria Marine Construction Company, got its start

in 1924, with a contract to build 12 Bristol Bay sailing gill-netters.

Joe and Ac Mansker researched what had been previously built in Astoria

in the way of Columbia River gill-netters.

Ac took what they had learned, gave the hull more beam to carry Bristol

Bay’s bigger catches, and they had a design.

A partnership was founded, and named Astoria Shipbuilding.

Joe borrowed $5000 from his

mother and bought a piece of property on the Lewis and Clark River, which flowed

into Youngs Bay and thence to the Columbia. The partners liked the site, since

it included the entrance to a slough, which formed a natural harbor off the main

river. The slough entrance came to

be called “The Pothole”, and proved to be a vital part of future expansion

of the yard.

A shed and a launching ways

were built and Astoria Shipbuilding was in business. Joe and Ac continued designing boats. Ac designed the Arrow No. 2, which served Astoria as

the river pilot launch for many years. In

1925 they built a boat for Joe, the Kingfisher, which he then used to do a bit

of commercial salmon trolling, a bit water taxi service, and a bit of towing,

all trying to make ends meet.

In 1927, Dr. H. C. Watkins

of Hoquiam, WA ordered a 65-foot diesel cruiser, the Ruth E. Joe designed

her and the small Astoria Shipbuilding crew built her. Dr. Watkins used her

briefly, and sold her for towing.

Although active, Astoria

Shipbuilding did not have enough business to support both Joe and the Manskers.

So, in 1926 Ac and Clair moved to Puget Sound to pursue their luck with

the well-established yards in that region.

Ac took his drawings of the Bristol Bay boat with him as he looked for

work. At one salmon packer they asked him to leave a copy of the

plans, which they would study and call him back.

He never heard from them again, but years later learned they had built

over 100 boats to his plans.

Ac, Clair and Joe remained fast friends even though the partnership had not succeeded. Clair worked at several yards before returning to Astoria. Ac went on to a successful career as a shipwright superintendent at various yards on Puget Sound. He was often called in for especially difficult projects. He was the superintendent in Bellingham during WWII, and finished his career as the shipwright superintendent at Todd Shipyards in Seattle.

It is a tribute to Ac that today the shipwright superintendent at Todd is still in charge of the alignment of all modules during new construction, and is in charge of all launchings. About 20 years after his retirement, Ac died at a Todd launching he had come to watch with Joe’s son Tom.

The Early Years

After the Astoria

Shipbuilding partnership ended, Joe started a new company at the little shed by

the “pothole” and named it Astoria Marine Construction Company, later to be

known as AMCCO. Joe worked as

both a boat builder and naval architect. Gradually

the little shed grew, the launching ways became haul-out ways, and eventually a

larger set of ways was added. Joe

designed the cannery tender Man o’ War, but lost the contract to build

her. Other boats of this period included the Port of

Bandon, Trallee, Evening, John Day, and a tunnel-stern gill-netter.

One of the more unusual

jobs AMCCO did in these days was the installation of sheet metal ice sheathing

to the bows of deep draft wooden freighters, known as steam schooners, bound for

Portland during the occasional very cold winter. The Columbia River was frozen with relatively thin ice far

downstream. Vessels breaking this

thin ice found that it cut through their hulls like a knife, and thus they

required sheathing.

A particularly significant

project in 1931, was the design and construction of the 120’ car ferry Tourist

III. She was to be the flagship

of Capt. Fritz Elving’s Astoria – North Beach Ferry Co. Fritz was a well-known waterfront character, and a tough old

Swede, then engaged in a bitter rivalry with the Columbia Transportation Co.,

for dominance in the ferry business between Astoria and the north shore of the

Columbia River.

The Tourist No. 3, 233 tons, 108.6’ x 37.5’ x 10. 3’, 425-horsepower diesel.

Elfving took a liking to

Joe, who was only 33 years old at the time.

Joe labored hard on the design. Although

he was a graduate engineer and had designed a number of fishing vessels, he was

in fact self-educated in naval architecture.

The Tourist III was not only the largest vessel he had designed,

she was also to be inspected by what is now the US Coast Guard.

All the plans had to be reviewed and approved, and a sophisticated

stability analysis had to be provided. He

always remembered this project as the challenge, which he was proud to say, made

him a real naval architect.

Designing the Tourist III was just the beginning of the challenge however. AMCCO was too small a facility for her construction, so space was leased at the Port of Astoria. Elfving wanted his boat built, and built now! Joe assembled his crew and they went to work. Incredibly, they were done 90 days later.

When asked how in the world he built a 120’ wooden ferryboat in 90

days, Joe said, “I’m really not sure, I was so busy getting out plans and

buying materials, it just all sort of happened.

We had a crew of extremely good shipwrights. They didn’t need

supervision; they all knew what to do. Fritz

was there every day and made sure everyone was working hard.

We were all a little afraid of him”.

After the Tourist III was completed, Elfving’s rivalry with Columbia Transportation Co. really heated up. One morning Elfving came to the boat for the first run of the day only to find his rivals had driven piling such that she could not leave her slip. Elfving was angry, determined, and had great faith in the Tourist III. He began surging the boat back and forth in the slip, battering the piles on every surge.

Gradually the piles broke

or were pushed aside, setting the boat free.

The Tourist III made her morning run, and two years later Columbia

Transportation threw in the towel. Elfving

now had a monopoly on the ferry service. Elfving

ran Astoria – North Beach Ferry Co. until 1945 when he sold his operation to

the State of Oregon. The Tourist

III continued operation until 1966 when the Astoria – Megler Bridge was

completed. She was then taken to

Kodiak, Alaska for a new career as a floating crab-processing facility.

In 1929, like almost every

other American business, AMCCO was hit by the great depression.

Geno was running the local Red Cross office, and remembered putting her

paycheck in the kitty to help Joe make payroll.

Joe's mother Annie, whose father had founded Callender Navigation, a tugboat company

that had merged with Knappton Towboat, was dismayed to see her dividends go to

nothing. This left her in serious

difficulty. She went to the

management of Knappton and told them she understood their problem, but they had

to understand hers as well. Henceforth

she expected them to bring all their Lower Columbia repair work to her son at

AMCCO. They agreed, and began a long and happy business

relationship.

The Birth of the CROD and other Yachts

The Columbia River Yachting Association approached Joe in

1934 to design a one-class racing and cruising sloop. The resulting Columbia River One Design, or CROD, met all the

requirements and became a fixture in the local regatta scene for the next thirty

years.

CROD #2, Jean II, owned by Dean

Webster of Portland, and sailed by Dr. A. Holmes Johnson, left Astoria on her

maiden voyage, not for Portland, but ambitiously for Victoria, British Columbia.

Johnson’s plan was to enter her in the Pacific International Yachting

Association races. After a

successful but stormy trip up the Washington coast to Victoria, the Jean II

placed first in her class in the races.

Nine CRODs were built between 1934 and 1940, five at

AMCCO,and four from AMCCO kits. An

active racing schedule soon grew, with a CROD class in most major Portland

regattas, as well as at the annual Astoria Regatta. “CROD row”, a row of

moorages directly in front of the Portland Yacht Club became famous, and at one

time had most of the CRODs then in existence moored in a line.

Before the days of fiberglass molds, this was considered a very

successful effort at establishing a one-design class.

Three more CRODs were built after WWII, including Joe’s

own boat, Tom Tom. Joe

decided that having your head and shoulders in the weather while cooking was not

such a good idea, and built Tom Tom with a full headroom doghouse over

the galley. Several other CROD

owners liked this change and added doghouses to their boats. Tom Tom eventually passed to Joe’s son Tom who sailed her

on Puget Sound for thirty years before passing her on to JoLee and Dennis Ford

of Longview, WA. JoLee is a long

time Dyer family friend, partially named for Joe. [Ed. note: in 2008, Tom Tom sold again, this time to Tor Woo of Seattle. She is now moored at Shilshole Marina in Seattle.]

Tom Tom, The Next Generation: the Ford kids on an outing in the San Juans a few years back.

In 1935 A. N. Prouty, a

local mill owner, commissioned Joe to design a new boat. She was the Joanne, a 36 foot express cruiser, capable

of speeds up to 14 knots. Next Dr.

Wallace Haworth of Portland ordered Phantom, a particularly luxurious 50

footer, powered by twin V-8 engines.

Phantom heads in for repairs in 2002. See the magnificent outcome in Gallery 4 Phantom

In 1937 Portland businessman Milt Henderson approached Joe

about design and construction of a new powerboat.

Henderson had an existing boat, the Blonde, which had once been a

cannery tender. He knew he wanted

another heavy-duty boat. He invited

Joe and Geno to join him and his wife, Cynthia, for a cruise in British Columbia

aboard the Blonde. Joe came to understand Henderson’s taste in boats.

Henderson was quite clear in his requirements, and the conceptual design is his;

he left the naval architecture to Joe. The

result was the 47-foot Evening Star, launched in April of 1938.

Evening Star circa 2000

Watch a video of Evening Star now! Join Tom Dyer and Lise Kenworthy and guests Cheryl and David Kanally for an evening aboard.

At about the same time, J. W. “Mac” McRae of Portland decided he wanted a new boat as well. Rather than getting an expensive custom-built boat, McRae opted to by a 45-foot “kit” boat from a manufacturer in Bay City, Michigan. He then decided to have AMCCO assemble the kit for him. His new boat, to be named Marymack for his two daughters, was built alongside Henderson’s Evening Star. Every time McRae saw a feature he liked on Evening Star, he asked Joe to incorporate it in Marymack.

As a result the two boats have many features in common, but

Marymack was built as a finely finished yacht with a varnished mahogany

house. Evening Star, true to

Henderson’s vision, was also finely finished, but with a painted workboat

style house. As AMCCO built Marymack,

Joe often found wood in the Bay City kit that did not meet AMCCO’s high

standards. Joe had no second

thoughts about pulling a better piece out of inventory.

When McRae complained about the cost, Joe explained that he bid the job

at a price, and that price would stand, modifications and substitutions not

withstanding. Joe was an artist first, and a businessman second.

Merrimac (originally Marymack) circa 2000. For more on Merrimac, see Gallery 5.

Next, in 1938, came a

52-foot gaff-rigged schooner designed by Fenwick Williams for Edward Hefty of

Portland. She was named the Pagan.

The People

Joe knew he could not do all of this by himself, and

gradually put together a team of top-notch wooden ship builders.

The

AMCCO log shows many of their names: George

McLean, John Puranen, John Omundson, Clair Mansker, Joe Hillard, Bryan Ross, Art

Olson, Cappy Hillard, Bob Taylor, Gust Suominen, Charlie Malagamba, Gib Larson,

Jack Huhtala, Charli Utterback, Joe Bowlsby, Bill Maki, George Huhtala, Jess

West, Swede Zankich, Harold Dahlgren, Truman Cook, and Heine Dole.

A key player joined the staff in 1935.

This was John Omundsen. John’s

father had served a traditional Norwegian shipwright apprenticeship in the old

country, complete with listening to the master’s wife read from the Bible

every night while he carved treenails by firelight.

John’s father gave John a similarly rigorous education in boat

building. John learned his trade n

Wisconsin and came west to work in St. Helens, Oregon during WWI, establishing

an excellent reputation. When Joe

hired him, he brought him to the yard, and introduced him to the foreman.

The foreman asked John to install the joiner work in the fo’c’sle of a troller under construction. John got right to it, and disappeared into the fo’c’sle. He came out for lunch, with no evidence of having done any work. The foreman decided to keep an eye on him. That evening he went to Joe and said “that new guy isn’t so hot, he hasn’t done anything all day”.

Joe said John had a good reputation, so leave him alone and see what he is up to. The next day was a repeat of the first, and the foreman was getting agitated, when in mid afternoon John emerged from the fo’c’sle and went to the joiner shop. He immediately began choosing and cutting material. The next day, when he was done cutting, he loaded all the pieces on a lumber cart and headed back to the troller.

By the next day all the pieces were installed, all fitting

perfectly. Instead of measuring and cutting one piece at time, as almost any

other shipwright would have done, John had divided the job into three phases:

measuring, cutting, and installation. He

saved several score of round trips between the troller and the joiner shop, and

did it with such skill that each piece required little fitting.

Many people credit John as being the finest shipwright they

have ever known. He could plane a

piece to fit perfectly with only one pass of the hand plane, or he could cut

pieces to fit perfectly, seemingly by eye, aided only by a story board he had

prepared in the mold loft. He could

build a hull, and then install all the joinery with the fine touch of a

furniture maker.

A 30's vintage ad touts the art and science of a Joe Dyer design. (Image courtesy of Chuck Kellogg and the Portland Yacht Club)

Clair Mansker returned from Puget Sound in 1936 and took

over the foreman duties as well as those of head loftsman.

Joe and Clair developed a number of innovative ways to build a boat.

It took Joe’s engineering point of view and Clair’s superb skill as a

loftsman to make much of it happen, but years later Joe characterized their

advances as just one more small step in the 3000 year evolution of wooden boat

building.

They knew that as much work should be done as early as

possible in the building process, a technique fundamental today in sophisticated

computer driven shipbuilding. AMCCO

boats were often taken on their trial trips on the day they were launched.

Each part was fully developed on the mold loft floor; all pieces would

have rabbets, bevels, etc. marked on their templates.

Frames were sawn with exact bevels smoothly varying from waterline to

waterline. Dubbing of frames was

virtually unknown at AMCCO.

More unusual was the practice of building a bent frame hull

“inside out” by erecting bulkheads on the keel, adding intermediate molds as

necessary, installing the shelf, clamp, stringers, engine beds, ceiling and any

intermediate harpins necessary. The

frames were then bent over the ceiling, harpins and stringers, from the outside

of the hull. This reduced the

amount of temporary molds and ribbands required, allowed a larger framing crew

to bend frames around a largely convex shape, and allowed pre-outfitting the

hull with engines, tanks, major piping, shafting, etc. while the hull was

relatively open. Using these

techniques, a crew during WWII completely framed a 137’ YMS in less than 16

hours. This was typical of the way

Joe and Clair thought, always looking for better ways to build what today is

called a traditional vessel. To

them it was not a tradition, rather an ongoing perfection of their craft.

Once the hull and joiner work were complete, Sid Snow, an

Englishman who had been a furniture finisher in the old country, finished them.

Sid applied his skills and an artist’s eye to every thing he touched.

As result AMCCO boats achieved a reputation for the highest quality paint

and varnish work.

Sid was not the only immigrant working at AMCCO. Astoria was home to a large Finnish community. All of them were hard workers, and many were excellent shipwrights. Several worked at AMCCO for many years. Gust Suominen had served his apprenticeship before coming to Astoria. Jack Huhtila had been a ship’s carpenter in notoriously undermanned Finnish sailing ships.

A 30's era ad highlighting larger motor yachts designed by Joe Dyer. (Image courtesy of Chuck Kellogg and the Portland Yacht Club)

Jack occasionally would tell of the night in the Gulf of

Alaska when his ship was laid nearly on her beam ends with many sails still

standing. Her crew was simply too

small to furl the sails fast enough to save the ship.

The captain called Jack, who as carpenter was generally exempt from

working aloft, and asked him for help. Jack

went aloft with a knife and one by one punctured each sail.

As soon as it was punctured, it blew out and reduced the pressure on the

ship. Jack completed his rounds,

leaving only the sails necessary to manage the ship in the existing conditions.

Perhaps this experience convinced him to leave the sea and settle in

Astoria.

But the beloved character amongst the Finns was John

Puranen. John’s speech was a

typical Astoria mixture of English and Finnish, dubbed by linguists as Finnglish.

Finnglish was flexible enough to be used as Finnish at home, and as an

approximation of English at work. The

trick in understanding a man like John was to translate his speech from Finnish

pronunciation to English pronunciation. Thus

a “port” was piece of finished lumber larger than a batten, but smaller than

a timber, while a “bord” was a round window often installed in ships.

When you were able to do that, it was evident that John was indeed

speaking English for your benefit, but a listener might be surprised at your

ability to understand Finnish.

AMCCO had many legends about its Finns, and it is probably

not true that all of them involved John, but it seemed they were eventually all

attributed to him. AMCCO was a

liberal user of copper naphthenate,

a green wood preservative. John was

impressed with any compound that could forestall rot. He decided to call the stuff “fountain of youth”, or in

Finnglish “bowl o’ yute”. Everyone

at AMCCO referred to copper naphthenate

as bowl o’ yute, to the point that a newcomer would believe that

it was a special AMCCO formulation.

Once John was working at a well traveled crossroads in the

yard, making a grating for the refrigerated space of a minesweeper.

When asked what he was doing he said he was making a “grade for de refr….,

the rerg… the rirf…, Oh de hell vit it, de icebox”.

Word got out about John’s difficulty with the word refrigerator, so

everyone stopped to chat and ask him what he was doing.

Everyone got the same reply.

Heine Dole remembers John for his sense of humor.

Once during World War II the yard was working a great deal of overtime

and people were getting tired. Heine

saw John in the morning after what had been a long day.

He asked John if he had gotten some rest, to which John replied “Vell

Heine, ven I got home, I hung my overalls on de hook and vent to bed, and ven de

alarm clock rang, dey vas still svinging.”

Another time John was installing the forefoot on the power

yacht Evening Star. The

owner, Milt Henderson, had wanted a silver dollar inlaid in the keel under the

forefoot, this in lieu of the traditional silver dollar in the mast step of a

sailing vessel. Henderson was

watching intently, and fingering the silver dollar in his pocket.

John was doing his usual careful job of fitting the forefoot just right.

Henderson had a lunch appointment in Astoria and really wished John would work

faster, but John was a craftsman and not going to be hurried.

Finally Henderson gave the dollar to John and asked that it be inlaid. When Henderson returned from lunch, the forefoot was fit and

bolted in place. He asked John if

he had inlaid the dollar, and John replied with a twinkle in his eye, “Mr.

Henderson, you’ll never, never, know.”

Of course many key employees were Americans.

Two brothers, Joe and Cassius “Cappy” Hillard were vital

contributors. They had come to

Oregon with the CCC during the depression, but soon were engaged in various

entrepreneurial work schemes. They

began doing various jobs for AMCCO, and eventually became part of the team.

Cappy was the repair shipwright foreman, known for his ability to be

constantly in motion. Joe was

the rigger and laborer boss. Joe

was one of those individuals every company needs: the man who can get the job

done when everyone else is stymied. Joe

Dyer did not always want to know how Joe Hillard accomplished what he did, but

he knew Hillard would always come through in a pinch.

Joe Hillard was a self-taught mechanical genius, who

converted two ancient furniture trucks into shipyard cranes still in use today.

Joe was also a very hard driver, known more for strength than finesse.

He once sent several college kid summer employees into an engine room to

move a large diesel engine with only crowbars for tools.

They tried but were unable to move the engine and requested some jacks.

Joe told them to get back to work with the crowbars. They then methodically bent each crow bar nearly double, and

returned them to Joe, who in exasperation found them the jacks they had

requested.

The list of other key employees is long and includes Jess

West, the machinist; Charlie Malagamba, the caulker; Bob Taylor, and Harry

Hofmann, an apprentice Joe Dyer convinced to go to college and who became the

chief naval architect at Chevron Shipping.

Matt Fiskal was the pipe fitter, always wearing two pairs of coveralls,

each with pockets stuffed with fittings and tools. Gib Larsen, Junior Olsen, and Jumbo Carlsen were among the

other employees of the day.

In the office, Louie Schaerer kept the books.

Louie was an old style bookkeeper, who could add five column figures in

his head while telling you all about the movie he had seen the night before.

As things got busier, Geno Dyer quit her job with the Red Cross and came

to work with Louie in the office.

By 1937 the yard was very active. Geno was leaving her job to have a baby, and Joe could see he

needed help both in the office and in engineering. Help arrived in the form of

W.H. “Heine” Dole. Heine was

also the son of a sawmill man, and had served an apprenticeship as a machinist

before getting a mechanical engineering degree from Stanford University.

W.H. "Heine" Dole

After Stanford, he had designed and built a cutter, Chantey,

for his own use. The depression was

in full swing and Heine had taken a job on a tug.

One day he found himself aboard the tug that had been delayed in Astoria.

He decided to pay a visit to AMCCO, to have a look at the by then

well-known yard, and to perhaps ask for a job.

Joe hired him then and there. Heine arrived ready for just about any

chore Joe had for him.

In late 1938 AMCCO received a very significant contract.

The Coast and Geodetic Survey (a precursor to NOAA) had commissioned

Seattle naval architect H.C. Hanson to design an 88-foot survey vessel.

This vessel was not only to have the latest surveying technology; she was

to be built entirely of pressure treated timber.

AMCCO had already been experimenting in the use of “Wolmanized”

lumber, and had built several CRODs with Wolmanized planking. But no one before had built a large vessel entirely out of

Wolmanized material.

AMCCO was awarded the contract, and proved to be the ideal

yard for the project. Clair’s

detailed lofting, Heine Dole’s engineering and organizational skills, and

AMCCO’s pre-cutting techniques were vital in this job.

Each piece had to be cut almost exactly to size and sent out for pressure

treating at a mill in Wauna, Oregon before the vessel could be assembled.

Because the Wolman salts only penetrate across the grain

for a short distance, and only several inches with the grain at the ends, the

specification allowed only minimal planing of the sides of a piece, and trimming

at the ends. All fastener holes had

to be treated with bottlebrushes and bowl o’ yute before the fastener

could be installed.

AMCCO lost $20,000 on the job, but the new vessel,

christened E Lester Jones, was the culmination of thirteen years of AMCCO

growth and experience, and the stepping-stone to the next chapter.

Approach of World War II

Phantom dons a coat of gray and a machine gun to serve her country in WWII.

In 1941, as American involvement in the wars raging in

Europe and Asia became more inevitable, the U.S. Navy began a shipbuilding

program. Here was an opportunity

for financially troubled AMCCO.

Although they looked at several classes of vessel, of particular interest

to AMCCO were contracts to build 137-foot YMS class wooden minesweepers.

Joe, Clair, Heine, John Omundsen, and others worked very

hard to prepare a building plan and a bid for the construction of four YMS’s.

Joe traveled to Washington to participate in the bidding

process for construction of the YMS. Joe

not only convinced the Navy he could and should build the ships, but he had the

courage to suggest a design change. He

noted that the Gibbs and Cox design used a 110 foot oak keel, its multiple

sections scarf-jointed together. Joe

suggested substituting a single 110’length of Douglas fir.

The eastern yards scoffed and said such wood was not available, and if it

were, what mill could cut it? Joe

replied the wood was readily available in Oregon, and could be cut at a mill in

Westport, Oregon. The Navy and

Gibbs and Cox agreed to the change, subject to inspection of the facilities and

confirmation of the availability of such timber.

On April 1, 1941, the Navy awarded AMCCO a

$1,312,000 contract to build four minesweepers. Now they needed a

shipyard in which to perform the construction. Joe was not sure how he would

finance it. Fortunately the Navy,

anticipating situations like AMCCO’s, allowed a 10% progress payment upon

laying of the vessels’ keels. AMCCO

bought some adjoining tideland pasture, designed sheds and building ways to be

built when the money was available, and laid four 110’ Douglas fir keels

amongst the tule weeds in the pasture. Clair

started lofting.

The Navy sent a delegation to see these impressive

keels, and Joe decided to have a little fun with them.

The rabbet in the keels had been cut with a Skilsaw, producing eight

pieces of 110’ scrap that Clair had planed into battens for use in the mold

loft. As the Navy delegation

entered the yard, Joe had about a dozen shipwrights lined up with a 110’

batten on their shoulders. They

were posted out of sight of the visiting dignitaries.

When the high sign was given, all 110’ of shipwrights and batten

strolled into view, blocking the inspection party’s path.

They strolled on across the path and into another part of the yard as if

this was just an everyday occurrence in Oregon.

The Navy was duly impressed, and issued a change allowing all West Coast

yards to build their vessels with keels from the mill at Westport.

After receiving the first progress payments, AMCCO built new facilities specially laid out for the production of minesweepers and other similar craft. The size of the yard more than doubled in a few short months. A large building shed, or functionally four shed sections joined together, was built over newly completed launching ways and the four keels. The shed reflected AMCCO’s building philosophy. The two sections furthest from the river were for the basic construction of the hulls, including the installation of larger outfit items.

Outboard of these sections, at the river bank, were two

higher sections for outfitting and the installation of superstructures.

Ways connected the inboard and outboard sections, so that as a hull was

completed it was skidded from the inboard section to the outboard section,

taking the place of a sister vessel that had just been launched.

Three levels of outfitting shops divided the two parallel

shed sections. Bridges connected

the outfitting shops with the hulls.

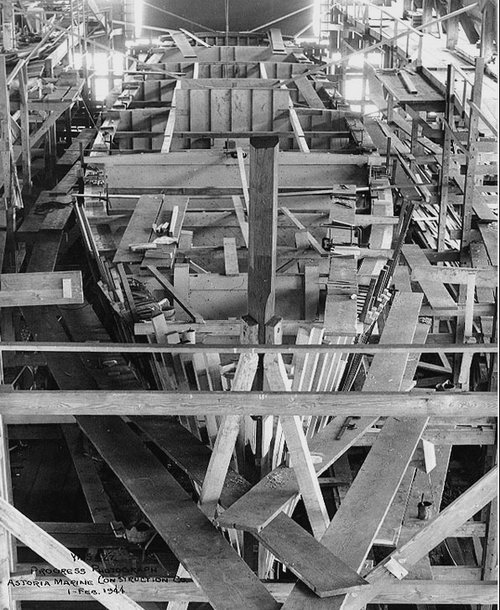

USS YMS 422 under construction at AMCCO, photo dated 1 Feb. 1944

When a YMS was launched, it was about 95% complete.

After launching the ship was towed to an outfitting pier in the

“pothole” where all the finishing touches were added.

Dock trials were in several cases held only 11 days after launching, with

builder’s sea trails the next day, and acceptance trials just 14 days after

launching. AMCCO was following in

the assembly line traditions of Henry Ford.

YMS 422, renamed AMS 28, "Osprey", during Korean duty, 26 April, 1952

The

YMS 422 traveled in convoy from Okinawa to Nagoya with the YMS 425 in Oct. 1945,

and in Nov. she traveled with the 425 from Nagoya to Bungo Suido. The 422 also

took part in the sweeping

operations around Kure and Kobe. The 422 was awarded two battle stars. In 1946,

the 422 and the 425 were part of a convoy that left Pearl Harbor for San

Francisco. After her designation was changed to the AMS 28, she took part in

minesweeping operations in Korea. In the span of one year, she was hit

three times by shore batteries at Wonsan, Songjin, and Kojo. Osprey was awarded

ten battle stars, a Presidential Unit Citation, and a Navy Unit Commendation.

In addition to the building sheds a machine shop was built,

supplanting a smaller existing one. This

shop housed not only a variety of machine tools (many of World War I vintage),

but a blacksmith’s forge and a small steel fabrication shop as well.

A sandblast shed was built; a larger area was prepared for lumber

storage, and another for parking. The

little office cottage was raised and an additional office was built under it.

AMCCO was now a full-blown industrial facility.

July 6. 1944 progress

photo of YMS 424, Launched 12 August 1944; Completed 24 November 1944; Grounded

and damaged in typhoon, Okinawa 9 October 1945 (see inset). Destroyed Dec 1945.

AMCCO now employed about 400 men. A new management structure was required.

Heine Dole was promoted to Vice-President, with responsibility for

engineering and production planning. Clair Mansker became the

General Superintendent, running the yard through a group of craft

superintendents. John Omundson was

made the Hull Superintendent, in charge of every aspect of hull construction. A

local engine dealer, Truman Cook, came aboard as chief mechanical engineer, as

did a local electrical contractor, Harold Dahlgren, as chief electrical

engineer. Each craft had a superintendent drawn from the ranks of the

experienced work force. The original cadre of craftsmen almost all became

foremen or leadmen in the expanded organization

USS YMS-425, commissioned 21 December 1944; Decommissioned, 19 July 1946; Retained in 1st Naval District as a Naval Reserve Training Ship; Reclassified a Motor Minesweeper and named Siskin (AMS-58), 1 September 1947.

On the administrative side Joe hired George Sheahan.

George had just gone broke in a clam canning operation in Seaside,

Oregon. As it turned out, this was

no indication of his business acumen. Joe

was in fact a poor businessman. George

McLean had tried to get Joe to put AMCCO on a sound business basis, but the

depression and Joe’s disinterest made the task impossible.

George Sheahan was fortunate in two regards.

He was able to get Joe’s attention, and he had the war income to work

with.

George Sheahan was very different from Joe, given to fine

suits, ascots and smoking jackets; but George and Joe became good friends.

George’s position was corporate treasurer, but he did much more than

this. He set AMCCO up as a

business. Years later Joe remarked,

“I never really understood what happened. I just kept building boats as I always had, but before George

came on board I was losing money, and afterward I was making money ”.

Heine remembers the day that George reported back to the other officers

that he finally had Joe convinced that he could not “spend a nickel” without

George’s approval.

The Astoria Marine Construction Company, circa 1950

Despite being the president of such an impressive

organization, Joe’s office remained in the engineering department, at a desk

alongside those of Clair and Heine.

Joe was particularly proud of one YMS which hit a mine in

the South Pacific, blowing away all of the ship forward of the engine room

bulkhead. But the bulkhead

survived, as did the engine room and the after steering station. The surviving crew was able to navigate the remaining hull

back to port. Joe always carried a

photo of the bulkhead, given to him after the war by a grateful survivor.

Baby Flat-tops

Of course AMCCO was not the only shipyard busy during the

war. In the Portland area Kaiser

was operating three big yards, delivering one ship per day.

The Vancouver yard was delivering one escort class aircraft carrier (CVE)

a week.

Joe’s brother-in-law, Dave Thompson, became the

superintendent at the Port Docks. Dave’s

story is typical of the war years. He was a landscape architect whose construction experience

was the construction of the Army’s Camp Adair near Corvallis, Oregon.

He was not a shipbuilder at all, but his administrative experience

enabled him to succeed in the difficult task of administering a constantly

changing list of urgent work requests from the Navy.

Toward the end of the war, AMCCO gradually slowed down.

The Navy brought in some AMCCO built boats for repair,

and established a reserve fleet at Tongue Point.

Heine Dole designed a new class of 79’ trawler, of which two, the Trask

and the Shirley Lee, were built.

A 58’ seiner was started on speculation, but did not sell for several

years. Joe also

decided it was time to complete his own CROD, the Tom Tom, which was

launched in 1945.

Various key employees returned to their prewar jobs.

These included George Sheahan, Truman Cook, and Harold Dahlgren.

Heine Dole stayed on for a while, but was chiefly involved in building a

new 47’ cutter, Katy Ford, for himself.

When Katy Ford was completed, he too left, moving to Olympia, WA

where lived aboard Katy Ford, set up practice as a naval architect, and

went back to his habitual summer activity of cruising the inland waters of

British Columbia and Alaska. Dave

Thompson moved to Portland where he became one of the Northwest’s leading

landscape architects.

Of the various superintendents, foremen, and lead men who stayed at AMCCO, most went back to working on the tools. Joe earned great loyalty from them when he left most of them at their elevated pay rates. Of course if a big job came along, some of them would assume their supervisory roles again until the job was over. One of the advantages of being in a small fishing and logging town became evident as AMCCO built back up briefly for the occasional larger job.

Many former employees went back to logging or fishing after

the war. But generally more money

could be made, more comfortably and more safely, in the shipyard.

So AMCCO maintained a cadre of workers who would leave their logging

jobs, or tie up their boats, when AMCCO called. Many of these workers did not

even clean out their lockers when laid off, because they knew they would be back

to work in a few months.

AMCCO did hire two new workers during this period.

One, Don Fastabend, went on to own

and manage AMCCO in later years.

The other new hire did not really work for AMCCO, but

directly for Joe. He was Tommy

Dyer, Joe and Geno’s son. Tommy

started work the summer he was 9 years old, coming in with Joe in the morning,

and working until Joe took him home at noon.

For this Tommy received 10 cents per hour.

Of course at first he was more of a mascot than a real worker, but

between Joe and the crew they found ways he could work productively, and as he

grew older he was given more demanding jobs.

He became a helper in virtually every trade, and began working regular

hours at union scale when he was old enough to be legal. Tommy, later Tom,

worked during every school vacation for 14 years, until leaving for graduate

school to study naval architecture.

The new reserve fleet at Tongue Point offered opportunities. The Navy, and the Maritime Administration, were “mothballing” ships to have in reserve in the event of another war. Mothballing generally consisted of repairing all gear in need of repair, filling machinery with rust preventative compound (a heavy oil), applying a heavy coat of paint, and installing de-humidifying machinery. The Navy made their facilities at Tongue Point available to civilian contractors. Of particular importance were two ARD floating dry-docks, large enough to dry-dock LST’s and other vessels too big for the AMCCO facility. AMCCO began bidding on doing this kind of work, and began to build an organization at Tongue Point.

The Korean Conflict

As the cold war heated up, and we went to war in Korea, the

Navy became acutely aware of advances made in magnetic detonators for mines.

Even existing wooden minesweepers, like the YMS’s were vulnerable to

the new technology. New

minesweepers had to be built without using a single piece of magnetic material

in their construction: no iron engine blocks, no steel fasteners, not even

magnetic pocketknives. This was a

huge challenge, calling for the special manufacture of engines, guns,

electronics, everything found on a modern ship.

All had to be especially made of bronze, aluminum, monel, or certain

stainless steel alloys.

AM 480 under construction, October 25, 1952

And once the Navy had found sources for the special

equipment, shipyards had to be found to build the ships.

AMCCO was chosen to be the west coast lead yard for the AM program, while

Luders in Stamford, Connecticut was chosen to be the east coast and national

lead. A lead yard was expected be

first in the building process, sharing engineering, knowledge, patterns made,

and so forth with the yards following them.

It was a tribute to AMCCO to be chosen as west coast lead. As things

ultimately developed, AMCCO passed Luders, and shared the national lead duty

with them.

The original contract was for two ships, AM 480, the

USS Dash, and AM 481, the USS Detector. Eventually AMCCO received a contract to build three more

ships for the Royal Netherlands Navy.

Although only five ships were involved, compared to the

dozens built during World War II, the number of vessels is not reflective of the

effort involved. These ships were

considerably bigger than previous AMCCO built vessels, and very much more

sophisticated. They were, at the time, the most expensive ships ever built

on a per foot basis. AMCCO’s

contract was for about $2,000,000 per ship, but the value of the special Navy

furnished non-magnetic equipment was another $3,000,000. The

value of the entire operation was perhaps most evident in a visit to the “gold

room”, where crate after crate of gleaming silicon bronze fasteners were

stored.

Sophistication was not limited to the non-magnetic

equipment. The forests were running

out of old growth timber necessary to build ships of this size, and the Navy was

interested in building stronger hulls. The

result was a plan to build the ships of laminated oak and fir.

Construction would be a mixture of traditional wooden shipbuilding and

modern laminated construction. The

keels, stems, frames, and all other major internal structure was to be laminated

in single pieces. This meant, for

instance, that frames were continuous horseshoe shaped members, spanning from

deck edge to keel and on to the opposite deck edge.

To

make room for this new way of building ships, the two smaller sections of the

YMS sheds were converted; one to a glue or laminating shop, the other to a saw

shed. The saw shed required a very

large flat floor, big enough to rotate a complete frame on wheeled dollies

through a planer or ship saw. The

two remaining sections of the big shed would house the AM hulls, albeit with a

bit of hull hanging over the center that separated the larger sections from the

smaller sections.

In

addition to reconfiguring existing space, a sheet metal shop was built for a

subcontractor, Rice Sheet Metal. It

was not possible to simply purchase non-magnetic sheet metal products. Joe Dyer

could not resist the opportunity, and ordered a set of monel gutters from Rice,

for installation on a new home he was building in Astoria.

The glue selected for the laminations was Resorcinol, which

even today is a superior adhesive. Each frame was built up of many oak planks.

AMCCO built three large clamping tables on which the frames were built. Interior clamps rode on radial beams, and were set to the

desired dimension of the inside of the frame.

Layers of planks were then spread with glue and bent around the clamps to

bring the frame to its desired outside dimension. Everything was clamped thoroughly (Resorcinol requires good

fit between members, and adequate clamping while curing), and a lid was dropped

over the clamping table.

After the frame cooled, it was taken to the saw shed where

it was planed to its final siding dimension and sawed

to its finished inner and outer dimensions, complete with the correct bevel at

each point of its perimeter. The

finished frame was then taken, in proper sequence, to the correct location on

the keel and erected. Once the

vessel was fully framed, a triple layer of fir planking was installed: two

opposing diagonal layers, and one fore and aft layer.

Each layer was fastened to the frames in the conventional way.

It may be fair to say that AMCCO built the world’s first cold molded

ship!

Of course this dramatic upturn in business required the

return to a larger management team. Shipwrights

again became superintendents, and fortunately, key players like Heine Dole,

George Sheahan, Truman Cook, and Harold Dahlgren returned. New management came

as well, in particular retired Rear Admiral John Keatley, hired especially to

oversee relations with the Navy. Part

of Admiral Keatley’s job was to make the Navy comfortable with an operation

where the president spent most of his time in overalls, and did not have an

office of his own.

The

AMCCO log of the period records other new arrivals: Pete Miller, Joe Tursi,

Windy Wilken, Ron Larsen, John Dale Omundsen, Toivo Sjoblom, Herman Johnson, Jim O’Conner, Harold

Piettela, Art Taylor and Bill Earl.

One interesting incident happened during the construction

of the first two AM’s. A new

immigrant from Finland applied for a job as a sweeper, apparently having no

other industrial skills. He seemed like a good man, and was hired.

He did a good job and became well liked.

One day he heard that AMCCO needed a photographer to take

progress photos required by the Navy. These

were to be professional quality photos of every

detail on the ships as they were being built.

Apparently this man had been a professional photographer in the old

country, and had brought his cameras and dark room equipment with him.

He applied for the job and was hired.

He was doing an excellent job when one day another new

immigrant spotted him. The second

man had been in the Finnish armed forces, and also knew the photographer to be

an ardent communist. He immediately

contacted AMCCO, who was prepared to question the photographer.

But the photographer never came to work again, and in fact was never seen

again in Astoria. He apparently knew he had been recognized.

The Office of Naval Intelligence was notified, but was not

concerned, in that no one, including the photographer, had been granted access

to any secret equipment destined for the ship.

Nonetheless it is interesting to wonder just how good a set of AMCCO

photos are stored in some forgotten warehouse in Russia.

Jess and Bob West: Two generations of master machinists Cliff West of Rainier, OR contributes these

memories about his father and grandfather who were both machinists at

AMCCO in the 1950s:

Jess West Passed away on October 17 1962 and Bob West Passed away on June 1 1991." Tom Dyer adds these memories about Jess West:

"I remember your grandfather very well. "The tools were mostly war surplus (WW I that is). You had to measure everything very carefully, since you could not blindly rely on the tool. It seems to me your grandfather had some machine tools that belonged to him and were probably in better condition. I do not know if the company bought them when he retired. I also remember he was real nice to me when I was a little kid hanging around the shipyard."

|

Another aspect of the heating cold war was the business of

de-mothballing the ships, which had so recently been mothballed. These ships

were then given to South Korea, Taiwan, and our other new allies.

The work mostly took place at Tongue Point, and used the same basic team

that had done the mothballing, although after the AM program was completed it

was not uncommon to bring some of the work to the AMCCO Lewis and Clark yard.

De-mothballing was an interesting business, because bids

were based on the condition the vessels were supposed to be in when mothballed.

Unfortunately some mothballing contractors were more conscientious than

others. It was not uncommon to find

mothballed engines, supposedly ready to go, that in fact required major

overhauls. The extra work was of

course all done on a cost plus fixed percentage change order basis.

Particularly memorable were the 3600 hp Fairbanks

Morse Model 38D81/8 engines used to power LSM’s. These

were vertical opposed piston engines, with a crankshaft on top and bottom.

Virtually any repair required pulling the upper crank, no small job.

These engines had been filled with Rust Preventative Compound (RPC)

supposedly after complete overhauls.

But in fact many had worn out piston rings.

On a number of occasions they would begin to run on the RPC, and then

begin sucking lube oil out of their crankcases and run on that as well.

The result was a violent runaway. It

was standard procedure to have a sailor standing by with CO2 to empty

in the air intake to shut the engine down.

Sometimes this worked, sometimes it did not, and on at least one occasion

the sailor dropped the CO2 bottle and ran.

The AMCCO old timers knew that standing in line with the cranks was fairly safe, since if any parts were going to fly, they would come out the side of the engine. Some runaways stopped themselves when they threw piston rods, others when they had burned all their lube oil and seized a main bearing. In any case, starting a mothballed 38D81/8 was always an adventure.

After the AM program was completed, as had happened after

World War II, a number of key managers again returned to their peacetime jobs,

and many superintendents found themselves once more working with their tools.

Truman Cook and Harold Dahlgren went back to their old companies, Admiral

Keatley retired, and George Sheahan became a successful

entrepreneur. Joe Dyer’s friendship with George continued as Joe

participated as in investor in many of George’s business ventures.

Heine Dole took Katy Ford back to Puget Sound, this

time to Gig Harbor, WA, where he resumed yacht design and summer cruising. In

1962 he and his new wife Peggy cruised Katy Ford for another seven years,

until when in 1969 Milt Henderson honored a long-standing first right of

refusal, and offered Evening Star to the Doles.

The Doles accepted, and enjoyed her for 31 years until 2000, when they

sold her to Tom Dyer, his wife Lise, and Joe’s grandson, Ben.

As the AM program wound down Joe again had time to think of

other things. Service in the

legislature, and learning public speaking, had placed him in a position of civic

leadership he never again left: United

Way Chairman, recipient of Astoria’s First Citizen Award, first chairman of

the Oregon State Marine Board (charged with overseeing state regulations

governing pleasure boat activity), founding member of the Columbia River

Maritime Museum, to name a few of his civic accomplishments.

He also continued to help promote boating in the Astoria

area. When Tom joined the Sea

Scouts, AMCCO rebuilt their 26’ whaleboat, and as a training opportunity for

Tom, AMCCO built a 14’ Blue Jay for the Sea Scouts as well. Several years later AMCCO and Tom built six 8’ El Toro’s

that were sold, loaned, or leased to yacht club members. The regional El Toro championship was held on Youngs Bay one

year, with Joe’s boat, Merrimac, as the escort.

This was the same Marymack AMCCO had built in 1938.

Mac McRae had given her up to the Coast Guard during the war, and decided

he did not want her back. Instead

he bought another boat he christened the Monitor. In 1952

she was back on the market, and Joe and Geno were pleased to buy her.

She was now named Princess, but after a lengthy debate with family

and friends, Joe and Geno decided she should be Marymack once again, this

time with the historic spelling. AMCCO

really spruced the boat up, repowering with a Buda diesel, adding a flying

bridge, making her bright work shine like new, and because she was Joe’s boat,

adding iron bark sheathing along the waterline, and tow bitts discretely placed

on the aft corners of the trunk cabin. Merrimac

is still a beautiful boat, now owned by the Bealls of Portland, and a

frequent winner in wooden boat shows.

One more yacht was built at AMCCO while Joe was still at

the helm. She was the cutter Patronilla,

designed by Heine Dole and built by John Omundsen in 1957 for Bill Forrest.

Soon thereafter, Omundsen took a leave of absence to build another Dole

designed sailboat, the 38’ ketch Ebb Tide.

She was built for Eben (Eb) Carruthers of Warrenton, Oregon.

Eb had a shop in which he built tuna packing machinery, and he wanted the

vessel built there so that he could participate to the maximum in the process.

AMCCO in 2005

Don Fastabend and the other owner/employees of AMCCO.

(Ed. Note: The remainder of this section is based upon an interview with Don Fastabend in July of 2003.)

"I came to work for them in 1950", said Don Fastabend, current owner and operator of Astoria Marine Construction. "The company had other operations besides this one, mostly for Navy contract work, including a yard at Tongue Point, on the other side of town."

Don Fastabend at his desk in the office of the Astoria Marine Construction Company

"That was during the Korean conflict", continued Don. "We were making the 165-foot AM. They were completely non-magnetic. With over 400 guys, we were at our peak in terms of employment and production."

"After the war, things really dwindled down," Don remembered. "The Navy based closed in 1959, and by 1960, our workforce had gone from 400 down to 15."

"I remember Joe Dyer coming to us sometime late in 1961 and telling us that by January 1, 1962, we would be closed down. We all understood, given the base closing, and how hard it would be to build up a commercial business after being a defense contractor."

"But then Joe had an idea to keep the yard going. He told us that as many of us that wanted in to the deal, he would turn over the operation to us, and we could operate the yard on consignment, if we would take care of all the bills. Joe would get 50% of the profits, and we would keep the other 50%. That way, we could keep working, and Joe could hang on to the yard."

"We each put in a thousand dollars as working capital. When we first started out, we had to work for no pay for a while. That got the group down to 11. By the end of the first year and a half, there were only 9 guys left."

"Then we saw the king crab business start to blossom, and that got us some real business. We wound up with the maintenance of five of the big king crab boats, and that was solid revenue." (ed note: one of these boats is still a loyal customer). Don continued, "We eventually got to the point of hauling out about 320 boats a year, which is a pretty good business."

"In 1968, Joe offered us a chance to purchase the business, which we did. We had paid it off by 1973. By 1975, the other partners had all retired. I was the youngest one of the bunch. The others have all passed away, and now I'm the surviving partner. Last year we hauled out about 120 boats. The business just isn't what it used to be."

Don reflected, "I'd like to find a way to retire soon. But we have some really fine guys working here. Skilled people. They have homes and families, and they've been loyal to us all these years. And our customers know they can count on us."

So, as was the case with Joe Dyer so many years ago, the Astoria Marine Construction Company continues to chug along, much like the 1911 Mack truck that powers one of the yard's cranes. The fuel that powers the yard has equal measures of skill, tradition, loyalty, and resilience. This place may go on forever.

1911 was a very good year.